Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia as Prediction Oral Lesion for HIV Disease : A Review Article Volume 5 - Issue 3

Nanda Rachmad Putra Gofur1*, Aisyah Rachmadani Putri Gofur2, Soesilaningtyas3, Rizki Nur Rachman Putra Gofur4, Mega Kahdina4 and Hernalia Martadila Putri4

- 1Department of Health, Faculty of Vocational Studies, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia

- 2Faculty of Dental Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia

- 3Department of Dental Nursing, Poltekkes Kemenkes, Indonesia

- 4Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia

Received:January 12, 2021; Published: January 19, 2021

*Corresponding author: Nanda Rachmad Putra Gofur, Department of Health, Faculty of Vocational Studies, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2021.05.000214

Abstract

Introduction: Oral Hairy Leukoplakia (OHL) is a hyperplastic mucocutaneous epithelial cell disease, induced by Epstein Barr virus (EBV). The clinical appearance of OHL is as white, corrugated, painless, and asymptomatic lesion, as a patch that cannot be removed by scrapping, located often bilaterally on lateral borders of the tongue. The prevalence of OHL was reported to be 20% in asymptomatic HIV infection in the United States to 36% with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Worldwide 2006, the prevalence of OHL in Brazil was 28,8%, also reported a prevalence of 38.8% and 21,8% in northern and southern USA.

Discussion: Oral hairy leukoplakia is a specific lesion in HIV infection caused by Epstein Barr virus, and has been reported in over more than 28% patients and is a sign of disease progression. OHL appear clinically as an asymptomatic, white, or grayish white, well demarcated plaque with corrugated texture [1]. The “hairy” surface varies in size from a few millimeters to extensive lingual and oral mucosal involvement. These lesion typically occurs on the lateral tongue but may also appear on the ventral and dorsal surface of the tongue, and more rarely, on the buccal mucosa.

Conclusion: The establishment of Oral Hairy Leukoplakia as a diagnosis have a diagnostic value for HIV infection. Oral manifestations are the earliest and most important indicators of HIV infection. OHL is often wrongly diagnosed and thus proper treatment is delayed. The present of OHL in the absence of known cause of immunosuppression strongly suggest HIV infection. In the early diagnosis of OHL, health care provider must be cautious and seek further examination to establish HIV infection.

Keywords: OHL; infection; HIV; oral lesion

Abbreviations: OHL: Oral Hairy Leukoplakia; EBV: Epstein Barr Virus; AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Introduction

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia (OHL) is a hyperplastic mucocutaneous epithelial cell disease, induced by Epstein Barr virus (EBV), and it is the first pathologic manifestation attributable to replicative EBV infection [1]. The clinical appearance of OHL is as white, corrugated, painless, and asymptomatic lesion, as a patch that cannot be removed by scrapping, located often bilaterally on lateral borders of the tongue [2]. In the prevalence of OHL was reported to be 20% in asymptomatic HIV infection in the United States to 36% with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) [3]. Worldwide 2006, the prevalence of OHL in Brazil was 28,8% [4]. Another study reported a prevalence of 38.8% in Thailand [5]. Reported prevalence rates in OHL vary considerably according to the clinical criteria used and the characteristic of the study population, such as the type of immunosuppression and clinical stage of the patients. Epstein- Barr virus is a human herpesvirus that is associated with important human diseases, including infectious mononucleosis syndrome, malignant lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In adults worldwide, the serologic prevalence of EBV estimated around 95%. Latently infected, circulating B-lymphocytes are believed to be a site of lifelong EBV persistence. The productive replications of EBV occur in the surfaces of the oral mucosa and sheds infectious, transmissible virus into the saliva [6]. HIV infections represent a spectrum disease that can begin with a brief acute retroviral syndrome that typically transitions to a multiyear chronic and clinically latent illness. Without treatment, this illness eventually progresses to a symptomatic, life threatening immunodeficiency disease known as AIDS. OHL has been associated with more rapid progression to AIDS among HIV viral-infected individuals, and with HIV viral loads exceeding 20.000 copies/ml, and with CD4+ counts below 200/mm [7,8]. OHL is a disease of minimal morbidity that does not always require intervention. This is due to the fact that OHL is a benign, asymptomatic, and potentially self-limiting lesion. Therapy is indicated when symptoms become troubling or when there is a need for cosmetic reasons [9].

Discussion

Oral hairy leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia is a specific lesion in HIV infection caused by Epstein Barr virus, and has been reported in over more than 28% patients and is a sign of disease progression [10]. OHL appear clinically as an asymptomatic, white, or grayish white, well demarcated plaque with corrugated texture [11]. The “hairy” surface varies in size from a few millimeters to extensive lingual and oral mucosal involvement [12]. These lesion typically occurs on the lateral tongue but may also appear on the ventral and dorsal surface of the tongue, and more rarely, on the buccal mucosa [13]. The characteristic appearance of OHL is caused by hypertrophy of the involved lingual papillae. In general, the lesion is painless and irremovable by blunt manipulation [13]. When the lesion became symptomatic, it may represent superimposed or coinfection with candidiasis [14]. OHL is a benign lesion characterized by abundant EBV productive replication. EBV (or also called human herpesvirus 4) is from the gamma subfamily of Herpesviridae [14-16]. The virus remains in lifelong latency by residing in circulatory memory B lymphocytes of the peripheral blood, which serve as the cellular reservoir of persistent latent EBV infection [17,18]. The virus is transmitted by means of mucosal excretions, for example, saliva, through shedding of EBV-infected oropharyngeal cells during viral reactivation [19]. It remains unclear whether EBV derives from reactivation of latent strains in the tongue epithelium or is acquired through contact with EBV-infected saliva or through EBV-positive circulating B lymphocytes [18]. Recent studies have shown that infected monocytes, macrophages, or Langerhans cells of the peripheral blood migrate through lamina propria into oral epithelium and infect terminally differentiated cells of the upper portion of the spinous layer, initiating productive viral replication and EBV dissemination [20,21]. These cells could be the source of reactivation for EBV productive replication [8,20,22].

OHL as prediction lesion in HIV disease

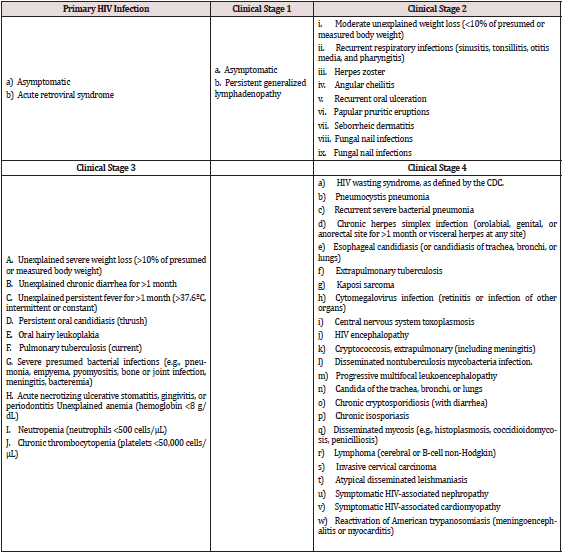

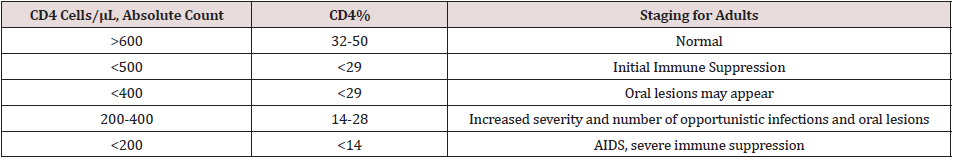

Severe immunosuppression can lead into reactivation of EBV replication in the oropharynx of EBV-seropositive patients. EBV replication has also been found in normal oral epithelium, this suggest that replication alone is insufficient for the pathogenesis of OHL and that cofactors are required [23]. The lateral border of the tongue is the most common location of OHL. The development of OHL on the tongue may be related to the accumulation of saliva in the floor of the mouth and the resting position of the tongue in a pool of EBV-shedding saliva [4]. Other explanation is the decreased number of Langerhans cells in OHL lesions when compared with nonregional oral mucosa. A comparative study of normal mucosa revealed that the lowest density of Langerhans cells was found on the lateral border of the tongue and the sublingual region. Thus, normal epithelium of the lateral and ventral sides of the tongue is more susceptible to EBV infection [23]. The importance of OHL as an indicator of immunosuppression was recognized soon after it was first described, when the authors observed that a proportion of the patients developed AIDS-defining illness within a relatively short time following the diagnosis of OHL [3,24,25]. In 1992 the European Economic Community published a revised classification of oral lesion associated with HIV infection in adults [26], where OHL is one of the lesions strongly associated with HIV infection as can be seen in Table 1 [27]. The findings of OHL in patients who are tested positive for HIV infection can give some predictive immune system condition of how progressive the infection is, as it is believed to have correlation with CD4 T cell counts. The rare occurrence of OHL in healthy individuals and the association of OHL in HIVpositive patients with low CD4+ T Cells Count and high viral load suggests a role of stimulation of EBV by HIV or a distinct role of CD4 T cells in protection against disease (Table 2).

Clinical manifestation of OHL

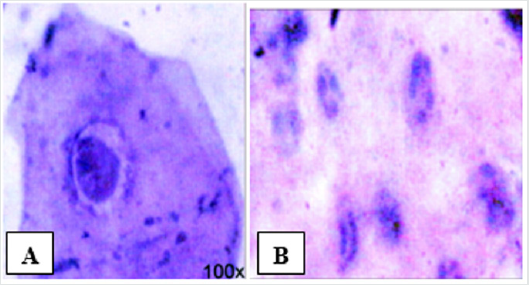

Clinical findings are usually enough to be a presumptive diagnose in patients with HIV infection. A further definitive criterion when necessary must be demonstrated by the presence of EBV in the lesions to be determined by histopathology, exfoliative cytology, in situ hybridization, or PCR [28]. Histopathologically, epithelial hyperplasia, hyper and parakeratosis, and ballooning, vacuolated, koilocytic epithelial cells with minimal or no surrounding inflammation [29], and also nuclei that have a ground-glass appearance and nuclear beading can be found in OHL. Exfoliative cytopathology of OHL revealed features of Cowdry type A inclusion bodies, ground glass nuclei, and nuclear beading. If the facilities to demonstrate the presence of EBV are not available, a lack of response to antifungal treatment or a demonstration of an immunodeficient status can reinforce the presumptive diagnose [30] (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis of OHL includes cancer or carcinoma in situ, hypertrophic candidiasis, lichen planus, hyperkeratotic leukoplakia [14] and frictional keratosis [4]. A complete history and physical examination and supported by further additional examination could help differentiate the diagnose. A propose to do a biopsy to determine the histopathology nature of the lesion was refused by the patient due to its invasiveness. PCR and in situ hybridization cannot be performed due to the lack of facilities. A cytopathology examination by scrapping of the lateral border of the tongue was performed. The scrapping was done by a cytobrush and directly smeared onto the glass slides, fixed in alcohol, and was then stained by the standard Papanicolau stain. The result of the cytopathology examination was smear consists of squamous epithelial, mononuclear inflammation cells and a cluster of coccus and hyphae also present. No sign of dysplasia and malignancy. The conclusion is a microorganism infection.

Figure 1: (A) Cowdry type A inclusion bodies along with perinuclear halo (B) Glass appearance of the nucleus and a peripheral nuclear beading, both (A) and (B) are PAP-stained, 100x magnification [30].

Treatment of OHL

Treatments for OHL when required consist of varying options. Usually, the institution of HAART with reduced viral load and increased CD4 count help a significant reduction in the prevalence of OHL patients. Systemic antiherpesviral therapy produces rapid resolution, although sometimes the recurrence can be expected when therapy is discontinued. Systemic antiherpesviral therapies known to be used are acyclovir and valacyclovir, with several reports the use of desiclovir and famciclovir. Acyclovir is a nucleoside analog available in the form of oral, intravenous, and topical. The triphosphate form of the drug is the active form, which has a potent inhibitory effect on herpesvirus-induced DNA polymerases but relatively little effect on host cell DNA polymerase [31]. In OHL, acyclovir effectively resolves the permissive infection, although cessation of treatment often results in a recurrence of lesions within 1-4 months [14,31].

Conclusion

The establishment of Oral Hairy Leukoplakia as a diagnosis have a diagnostic value for HIV infection. Oral manifestations are the earliest and most important indicators of HIV infection. OHL is often wrongly diagnosed and thus proper treatment is delayed. The present of OHL in the absence of known cause of immunosuppression strongly suggest HIV infection. In the early diagnosis of OHL, health care provider must be cautious and seek further examination to establish HIV infection. Institution of HAART after the diagnosis of HIV infection could induce the resolution of OHL. Other treatments such as systemic antiherpesviral accelerate the resolution process. The ability to recognize early OHL manifestation in patient with HIV is key to providing optimal and appropriate care, give early medical intervention and thus prolonging patient’s life and revise its quality.

Conflict of Interest

None

Funding

None

References

- Radwan Ozcko M, Mendak M (2011) Differential diagnosis of oral leukoplakia and lichen planus – on the basis of literature and own observations. J Stoma 5(6): 355-370.

- Sixbey JW (2008) Epstein-Barr Virus Infection. Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L, et al. (Eds.), Sexually Transmitted Disease. 4th Ed, McGraw Hill, New York, USA pp. 453-59.

- Moura MDG, Grossman SMC, Foncesca LMS, Senna MIB, Mesquita RA (2010) Risk factors for oral hairy leukoplakia in HIV-infected adults of Brazil. J Oral Pathol Med 35: 321-326.

- Walling MD, Flaitz CM, Nichols CM (2003) Epstein-Barr virus replication in oral hairy leukoplakia : response, persistence, and resistance to treatment with valacyclovir. J Infect Dis 188: 883-890.

- Triantos D, Porter SR, Scully C, Teo CG (1997) Oral hairy leukoplakia: clinicopathologic features, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical significance. Clin Infect Dis 25: 1392–1396.

- Greenspan D, Greenspan J (1992) Significance of oral hairy leukoplakia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral path 73: 151-154.

- Kerdpon D, Pongsiriwet S, Pangsomboon K (2004) Oral manifestations of HIV infection in relation to clinical and CD4 immunological status in northern and southern Thai patients. Oral Dis 10: 138–144.

- Uihlein LC, Saavedra AP, Johnson RA (2011) Cutaneous manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus disease. Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, et al. (Eds.), Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th Ed, Mc Graw Hill, New York, USA pp. 2439-2455.

- Nokta M (2008) Oral manifestation associated with HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 5: 5-12.

- Murtiastutik D (2008) Skin disorders in HIV / AIDS patients. Barakbah J, Lumintang H, Martodihardjo S (Eds.), Sexually Transmitted Infections. Surabaya AUP pp. 258-259.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA (2009) Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of clinical dermatology. 6th ed. New York : The McGraw-Hill Companies pp. 950

- Graboyes EM, Allen CT, Chemock RD, Diaz JA (2013) Oral hairy leukoplakia in an-HIV negative patient. Ear Nose Throat J 92(6): 12.

- Zunt SL, Tomich CE (1990) Oral Hairy Leukoplakia. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 16: 812-881.

- Miyashita EM, Yang B, Babcock GJ, Thorley-Lawson DA (1997) Identification of the site of Epstein-Barr virus persistence in vivo as a resting B cell. J Virol 71: 4882-4891.

- Jiang R, Scott RS, Hutt-Fletcher LM (2006) Epstein-Barr virus shed in saliva is high in B-cell tropic glycoprotein gp42. J Virol 80: 7281-7283.

- Walling DM, Ray AJ, Nichols JE, Flaitz CM, Nichols CM (2007) Epstein-Barr virus infection of Langerhans cell precursors as a mechanism of oral epithelial entry, persistence, and reactivation. J Virol 81: 7249-7268.

- Palefsky JM, Berline J, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS (2002) Evidence for trafficking of Epstein-Barr virus strains between hairy leukoplakia and peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Gen Virol 83: 317-321.

- Tugizov S, Herrera R, Veluppillai P, Greenspan J, Greenspan D, et al. (2007) Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infected monocytes facilitate dissemination of EBV within the oral mucosal epithelium. J Virol 81: 5484-5496.

- Walling DM, Ling PD, Gordadze AV, Montes-Walters M, Flaitz CM, et al. (2004) Expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent genes in oral epithelium: determinants of the pathogenesis of oral hairy leukoplakia. J Infect Dis 190: 396-399.

- Cruchley AT, Williams DM, Farthing PM, Lesch CA, Squier CA (1989) Regional variation in Langerhans cell distribution and density in normal human oral mucosa determined using monoclonal antibodies against CD1, HLADR, HLADQ and HLADP. J Oral Pathol Med 18: 510-516.

- (1993) Classification and diagnostic criteria for oral lesions in HIV infection. Classification and diagnostic criteria for oral lesions in HIV infection. EC-Clearinghouse on Oral Problems Related in HIV Infection and WHO Collaborating Centre on Oral Manifestations of the Immunodeficiency Virus. J Oral Pathol Med 22: 289-291.

- Graeme JS, Irvine SS, Scott M, Kelleher AD, Marriott DJE, et al. (1997) Strategies of care in managing HIV. In Managing HIV. Australasian Medical Publishing Company Limited, Sydney, USA.

- (2001) Clinician’s Guide to HIV-infected Patients. 3rd Patton The American Academy of Oral Medicine .

- (2007) World Health Organization. WHO Case Definitions of HIV for Surveillance and Revised Clinical Staging and Immunological Classification of HIV-Related Disease in Adults and Children p. 15-16.

- (2014) Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Basic : About HIV/AIDS.

- Diaz-Mitoma F, Ruiz A, Flowerdew G (1990) High levels of Epstein-Barr virus in the oropharynx: a predictor of disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Med Virol 31: 69-75.

- Reginald A, Sivapathasundharam B (2010) Oral hairy leukoplakia : An exfoliative cytology study. Contemp Clin Dent 1(1): 10-13.

- SchiØdt M, Greenspan D, Daniels TE, Greenspan JS (1987) Clinical and histologic spectrum or oral hairy leukoplakia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 64(6): 716-720.

- Elston DM (2011) Antiviral Drugs. Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, et al. (Eds.), Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th Ed, McGraw Hill, New York, USA pp. 2787-2796.

- Resnick L, Herbst JS, Ablashi DV (1988) Regression of oral hairy leukoplakia after orally administered acyclovir therapy. JAMA 259(3): 384-388.

- Lin P, Torres G, Tyring SK (2003) Changing paradigms in dermatology: antivirals in dermatology. Clin Dermatol 21: 426–446.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...