Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Dental Worker’s Contact with Covid-19 Confirmed Patients and Actual Performance of Infection Control Procedures in Dental Clinics Volume 7 - Issue 4

Hee Ja Na1* and Chenhao2

- 1Department of Dental Hygiene, Honam University, Kwangju, Korea

- 2Graduate of Dental Hygiene, Honam University Kwangju, Korea

Received: April 26, 2022; Published: May 13, 2022

*Corresponding author: Hee Ja Na, Department of Dental Hygiene, Honan University, Kwangju, 62399, Korea

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2022.07.000270

Abstract

Objective: This study analyzes the infection control procedures and performance status for dental medical institutions regarding infection control measures within dental clinics. It investigates by dental position, gender, and career those in contact with COVID-19 confirmed patients and identifies the level of infection control. This study aims to provide basic data for preventing coronavirus, suggesting monitoring dental workers in contact with COVID-19 patients should be managed by safety procedures, and blocking infections by air passageways in clinics, as well as managing facilities and dental workers’ safety.

Methods: In order to understand the general characteristics of the subjects of this study, the mean and standard deviation were obtained, and technical statistics by occupation were obtained for dental workers who had tested negative after contact with a confirmed coronavirus patient. In order to correlate air infection by gender and occupation, a response sample t-test was conducted by analyzing the occupation and contact experience of confirmed patients and dental clinic worker’s position, and in clinic spacing design to prevent infection as well as gender and room ventilation, and post-treatment disinfection. To analyze air infection in dental clinics, the automatic design for infection control within dental staff was cross-analyzed, and clinic ventilation by staff position was cross-analyzed according to position, as well as disinfection done after treatment, and ONE-WAYANOVA was done by position. Facility management and career correlation analysis were performed by both tests, and career regression analysis such as mask wearing, sharing refreshments and conversations, hand hygiene, washing work clothes, and monitoring infected employees were analyzed at a significance level of .05.

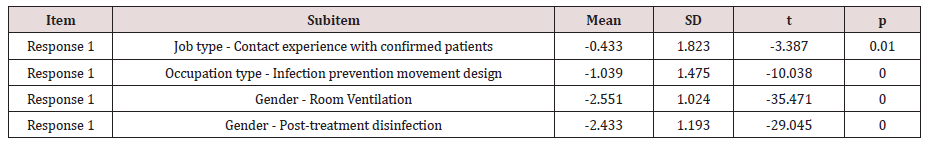

Results: The average and standard deviation of the job group tested negative after contact with confirmed patients in response 1. In the air infection management response sample t-test by gender and occupation the results were -.433 (1.823), t=-3.387 with a p value of 0.01, which is a significant level. note at 05. In Response 2, the mean and standard deviation by dental position and procedures to prevent infection movement were -1.039 (1.475), and the t=-10.038 p value was 0.00, which was significant at the significance level of 0.05. The gender of Response 2 and the mean and standard deviation of the treatment room ventilation are -2.551 (1.024), t= -35.471p values are 0.00 and are significant at the significance level of 0.05. Response 4 Gender and the mean and standard deviation in post-treatment disinfection are -2.433 (1.193), t = -29.045, p value is 0.00 and significance level is 0.05. These show a significant result as 05. The results of cross-analysis for dental clinic automatic design regarding air infection: For infection control by position, 57 people, 56.4% were the predominant category; but 16 people, 50.0% were highly likely for infection; and 14 people, 45.2% were nursing assistants. The results show a 2.5% ratio for 5 people who are ‘not very likely/ unlikely for infection’ and who are not risk factors. Cross-analysis was conducted to find out if there were significant differences in automatic design of infection control by position x2 = 16.960a, and the significance probability was .388, indicating that there was no significant difference in the automatic design for infection control regarding position at the significance level of 0.05.

Conclusion: F statistic 3.292, refreshments and conversations lead to regression of dental safety management. The significance probability .002 is a significant explanation for increased risk of infection due to position and casual contact while conversing and having refreshments; these were at the significance level of .05 (t=3.152, p=.002), the heightened risk due to these factors is explained as 0.077% of the total change (according to the modification coefficient, 0.054%).

Keywords: Dental clinic; infection control; dental profession; coronavirus-19; confirmed patient; air infection; facility management; safety management

Introduction

Recently, COVID-19 infectious diseases have emerged and are threatening the world, changing society as a whole. In these circumstances, it should be noted that dental institutions have a very high risk of infection [1]. This is because aerosols produced during dental treatment contain a combination of various microorganisms and viruses derived from patients, and there is a risk of causing pathogenic infection. The risk of infection is also very high in dental treatment itself, which is made by putting hands in close proximity to the patient’s mouth and directly contacting blood, saliva, and respiratory secretions. Patients with infectious diseases should be accurately distinguished and the infection route in clinics should be blocked, but this is practically impossible. Therefore, a system for preventing infection should be applied throughout patient treatment to prepare for the risk of infection under the assumption that all patients have infectious diseases [2]. The Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea announced infection control rules in 1992, began national measures for hospital infection monitoring, and identified the incidence rate and infection control status of domestic hospitals [3,4].

Since 2004, the Ministry of Health and Welfare has conducted a nationwide medical institution evaluation under the supervision of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and the infection control area has been used as an objective indicator in the evaluation of medical quality. In 2007, an evaluation pilot project was launched for dental hospitals affiliated with dental universities, dental hospitals affiliated with medical schools, and other dental hospitals, and from 2014, the hospital level was also included in the certification system. Even the Ministry of Health and Welfare (2018) admitted that infection control policies were implemented mainly in large hospitals, and that small and medium-sized nursing hospitals, clinics, and dental and oriental medicine hospitals were vulnerable to infection because only some items were applied. However, with the spread of COVID-19, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced guidelines for infection prevention and management at dental medical institutions. Infection management should prepare infection control rules and institutional rules for COVID-19 infection prevention and management through employee education. When there are a number of confirmed patients having COVID-19, it is necessary to identify the experience of dental workers’ contact with confirmed patients and cope with infection control of dental patients.

The more the public perceived ambiguity in information regarding the movement of COVID-19 confirmed patients within dental clinics, the more disruptions to dental treatment occurred. Employees of dental institutions should be trained on COVID-19 infection prevention rules, hand hygiene, wearing and removing protective equipment, patient monitoring by employees, and implementation of appropriate prevention measures. Along with these, patient reception and management should minimize waiting time by implementing an outpatient reservation system. Risk factors such as the patient’s COVID-19 symptoms and contact history should be identified when making medical appointments and receptions. In addition, in managing the entrance and waiting rooms, promotional materials such as a notice to prevent COVID-19 can be attached to the entrance, and if patients have fever or respiratory symptoms, they should receive screening treatment, and visitors should wear gloves for hand hygiene, masks, check for fever, and have their records accessed. Minimizing patients waiting time and maintaining appropriate distance (at least 1m) and providing infection control items such as hand sanitizers at the entrance, outpatient treating area, and waiting rooms is also needed. Dental care providers should prepare for patient risk management by selecting and wearing appropriate personal protective equipment according to the type of procedure being done before treatment.

During dental treatment following the aerosol generation procedure, area disinfection and ventilation should be performed after each treatment’s completion. In addition, appliances and materials used in environmental management should be disposed of in containers to prevent contamination of the surroundings, and treatment materials should be cleaned and disinfected (or sterilized) by appropriate means, with dental tools frequently cleaned with disinfectant and dental areas being ventilated after cleaning and disinfecting any other materials. In the reality that dentists are in charge of 88.1% of dental care [5], infection management has been left to autonomy of each dental clinic outside any legal regulatory system. Reflecting this reality, the Ministry of Health and Welfare operates an infection control program to implement general infection control principles, procedures and guidelines for each type of infection, and environmental management methods at medical institutions [6]. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1985) said that infection control programs, such as the establishment of a monitoring system, can reduce infections in medical institutions by 32%. The Ministry of Health and Welfare in Korea announced infection control rules in 1992 and began national measures for hospital infection monitoring as well as identifying the incidence rate and infection control status of domestic hospitals [7]. When looking at previous studies on infection in dental institutions it is apparent that there were no dental infection control standards in place in the early 2000s, referring to those previous studies, the recognition level and practice of infection control were mainly identified by dental hygienists in some regions [8-10].

After 2000, the Ministry of Health and Welfare announced the standard for preventing dental infection in 2006. While efforts to ensure patient safety through infection control continued, [11] certification evaluation was conducted on dental institutions by each clinic’s own recognition and self-monitoring, along with each clinic dealing with removal of medical waste and managing for infection risk environment, [12] the management status of other specific items such as wearing personal protective equipment, etc. was also done on a local basis [13]. The concept that infection prevention should be applied from the structural design of the clinic, and the necessity of recognizing infection passageway movements to prevent cross-infection among patients was done by each clinic every day after treatment [14,15]. Dental clinics are contaminated with a large amount of aerosol and dust generated by tooth deletion, prosthetic production, intra-oral surgery, and scaling. Therefore, it is necessary to partition each workspace when considering the treatment pathway and the occurrence of contamination. In addition, it is necessary to manage the environment and facilities with cleaning and ventilation. Dental institutions will also need to conduct surveys by occupation, gender, and career to understand the importance of infection control through unit chair management and water pipe management [1,16-18]. The purpose of this study is to identify dental infection control by classifying infection control levels across dental institutions by gender, and to analyze infection control, passageway ventilation and disinfection procedures as these relate to each occupational position in dental clinics. In addition, we will review mask wearing, causal contact through refreshment areas and conversation, hand hygiene, the washing of work clothes, and risks posed through infected employees by each dental care position and use specific areas of these criteria to cover the problems of infection management and provide basic data to block infection and improve medical services after contact with Covid patients.

Materials and Methods

This study conducted a study on 203 dental workers working at Y Dental Clinic, I Dental Clinic, H Dental Clinic, and S Dental Hospital in Gwangju Metropolitan City from April 1 to April 30, 2022, and dental technicians, and dental office workers. Participants in this study were surveyed as dental workers who had tested negative after contacting COVID-19 confirmed patients as well as those with official positions working at or entering dental clinics. Survey participants agreed to understand the purpose of the study and participate in the study, and the survey was conducted in a selffill manner. This study was conducted with the consent of the IRB (NO NO1041223-HR-04) at Honam University’s Bio Science Ethics Committee. When the sample was selected it was based on the general significance level of .05 and the effect size of 0.3 power of 0.95, using the G-power 3.1 program. The appropriate number of samples is 220. Therefore, samples were analyzed as a questionnaire of 203 people who had recovered, excluding those who marked the questionnaire with errors. The questionnaire was measured on the Likert 5-point scale Likert 5-point scale: 5 points from ‘very important’, to “It’s not important at all”. This criteria meant that the higher the score, the higher the degree of importance of practice.

Research tool

Air infection in the dentist’s office

The questionnaire to understand the infection control system and implementation status of dental medical institutions was prepared according to the guidelines for infection prevention (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2022) [3], measured on a Likert 5-point scale, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.836.

Dental clinic facility management

The questionnaire tool [11] to understand the infection control system and implementation status of dental medical institutions was prepared according to the guideline for infection prevention (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2022) [3], and measured on a Likert 5-point scale; Cronbach’s alpha was 0.763.

Safety management of dental clinicians

The questionnaire was prepared using appropriate management measures for dental equipment to prevent infection, infection control programs for dental institutions, development of disinfection and sterilization guidelines for medical institutions [11], along with any revision of medical institutions’ equipment and supply policies [17], and facilities methods to deal with medical waste [12]. The results were measured on a Likert 5-point scale, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.676 with a total of 5 questions.

Analysis method

The data collected in this study were analyzed using the SPSS 21.0 program. In order to understand the general characteristics of the subjects, the mean and standard deviation were obtained, and technical statistics were obtained for each dental position that had tested negative after contacting a confirmed patient with COVID-19. For the management of air infection by gender and occupation, a response sample t-test was conducted for analysis by position and confirmed patient contact experience, as well as job and infection prevention movement design, gender and clinic ventilation, and methods for post-treatment disinfection. In the analysis of air infection in the dental clinic, automatic design analysis of infection control was done by position, and cross-analysis of ventilation in the clinic also being done by position. Post-treatment disinfection, and ONE-WAYANOVA were also performed by position. Facility management and career correlation analysis were performed by both tests, and career regression analysis such as mask wearing, sharing refreshments, hand hygiene, washing of work clothes, monitoring infected employees and casual contact by conversations were all analyzed at a significance level of .05.

Results

General characteristics

In the general characteristics of 203 subjects; 56, 24.6% were men, 147, 64.5% were women; the average and standard deviation is 1.783(6.638); 80 people had 2 years of experience; 4 people had 4 years of experience; 4.5% had 6 years of experience; 4.8% had 10 years of experience within the average and standard deviation. In characteristics by position: 31, 13.6% were nursing assistants; 17,7.5% were coordinators; 32, 14.0% were dental hygienists; 10, 44.3% were dental attendance officials; 22, 8.6% were dentists; and the average and standard deviation was 3.325 (1.235). Characteristics by experience of contact with confirmed covid patients: 26, 11.0% had no cases of contact with confirmed patients; 20, 8.8% had contact with confirmed patients the first time; 20, 8.8% had contact with confirmed patients the second time; 52, 22.8% had contact the third time: 86, 37.7% had contact with confirmed patients the fourth time. The mean and standard deviation was 3.758 (1.405) (Table 1).

Response sample of air infection control by gender and occupation t-test

In the air infection control response sample t-test by gender and occupation, the average and standard deviation of the contact experience between dental position and confirmed covid patients in Response 1 is -.433 (1.823), t=-3.387p value is 0.01, which is a significant level. Note at 05 In Response 2, the mean and standard deviation by position and infection prevention movement design were -1.039 (1.475), and the t=-10.038 p value was 0.00, which was significant at a significance level of 0.05. The gender of Response 2 and the mean and standard deviation of the treatment room ventilation were -2.551 (1.024), t= -35.471p values were 0.00 and are significant at the significance level of 0.05. Response 4 Gender and the mean and standard deviation in post-treatment disinfection were -2.433 (1.193), t = -29.045, p value is 0.00 and significance level was .05. These showed a significant result at 05 (Table 2).

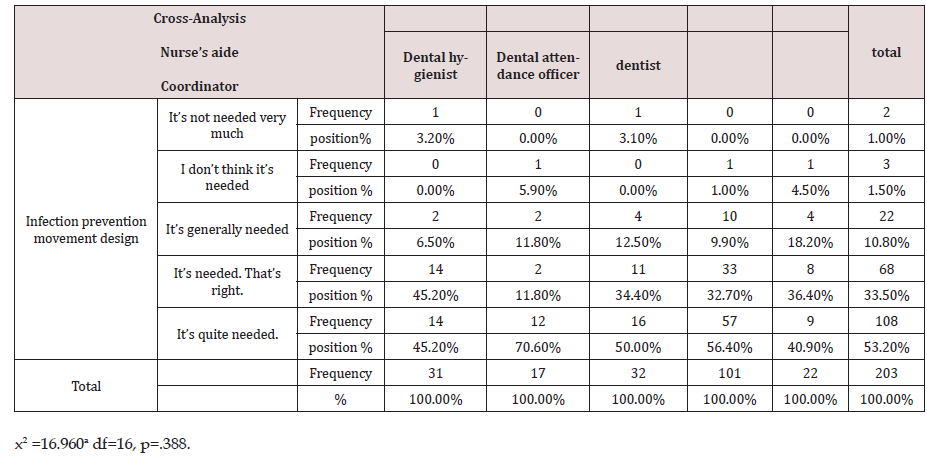

Air Infection in Dental Clinic: Results of Cross-Analysis for Automatic Infection Control

(Table 3) In the results for cross-analysis of automatic infection control according to position: For dental clinic air infection, dental attendance officials were the most predominant with 57 people 56.4%; these were followed by dental hygienists with 16 people at 50.0%; and then nursing assistants at 45.2%. These responses show a 2.5% ratio of 5 people who answered it’s not needed very much, or I don’t think it’s needed. As a result of cross-analysis to find out if there is a significant difference in the automatic design for infection control by position, there was no significant difference in the automatic design for infection control by position at the significance level of .05 with x2 = 16.960a and a significance probability of .388.

Table 3: Air Infection in Dental Clinic: Results of Cross-Analysis for Automatic Infection Control---(n=203).

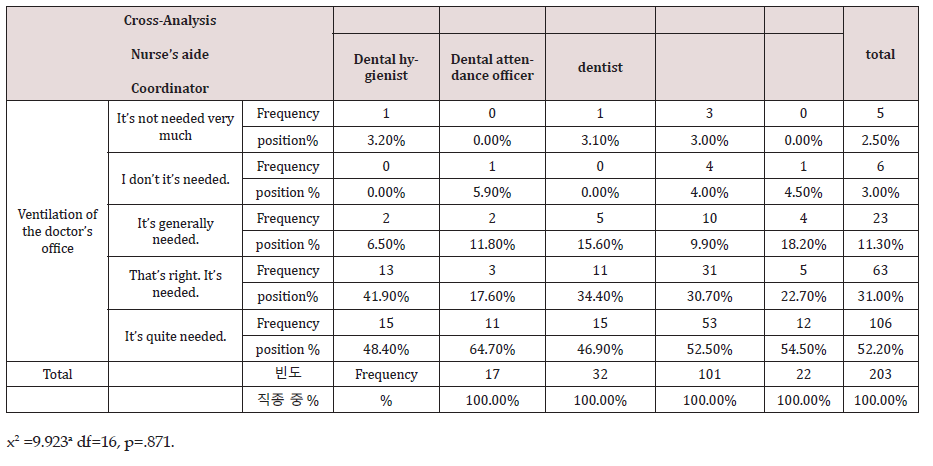

Air Infection in Dental Clinics: Results of Cross-Analysis for Ventilation and Occupation in Clinics

(Table 4) Dental room air infection: In the cross-analysis results for ventilation and clinic position, dental attendance officials, 53 (52.5%) answered it’s quite needed; and dental hygienists, 15 (46.9%), and nursing assistants, 48.4% also answered it’s quite needed. Throughout the dental profession, the responses showed a 5.5% ratio of 11 people who answered either it’s not needed very much, or I don’t think it’s needed. As a result of cross-analysis to find out if there is a significant difference in the automatic design of infection control by position, there was no significant difference in the automatic design of infection control by position at the significance level of .05 with x2 = 9.923a and a significance probability of .871.

Table 4: Air Infection in Dental Clinics: Results of Cross-Analysis of Ventilation and Occupation in Clinics---(n=203).

Air Infection in Dental Clinic: Results of Post-treatment Disinfection and Cross-Analysis by Occupation

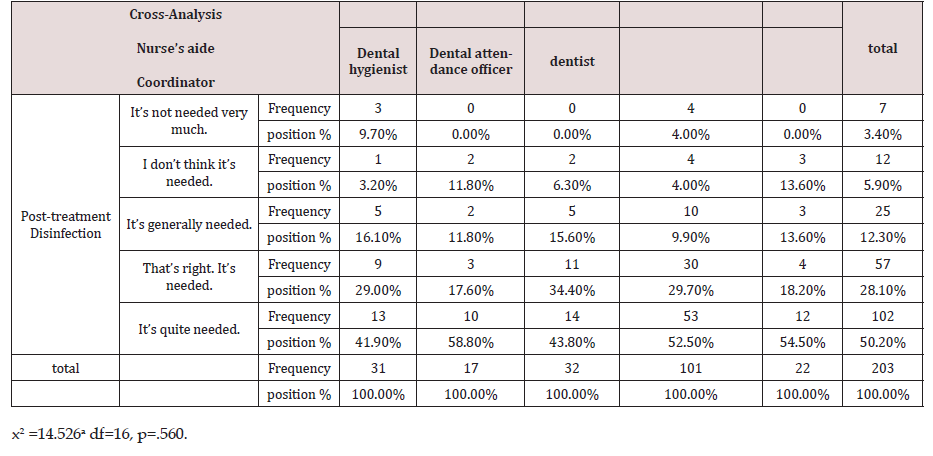

(Table 5) In the results for post-treatment disinfection and cross-analysis of dental clinic air infection: post-treatment disinfection and position: dental attendance officials, 52.5% were the most predominant; followed by dental hygienists, 14, 43.8% who answered it’s quite needed. Throughout the dental profession, the responses show a 9.3% ratio of 19 people who answered either it’s not needed very much, or I don’t think it’s needed. As a result of cross-analysis to find out whether there is a significant difference between post-treatment disinfection and position, x2 = 14.526a with a significance probability of .560; the responses found that there was no significant difference between post-treatment disinfection and position.

Table 5:Air Infection in Dental Clinic: Results of Post-treatment Disinfection and Cross-Analysis by Occupation---(n=203).

Correlation analysis between facility management and experience in the clinic

(Table 6) In the analysis of the correlation between facility management and position in the clinic, the post-treatment ball washing, and disinfection is 617, showing a high correlation. Subsequently, surface management and position after treatment are shown in the order of .155, and there is a low correlation between surface management and physical distance .021.

Dental care safety management: wearing masks, sharing refreshments and conversations, hand hygiene, washing with work clothes, monitoring infected employees and regression analysis for their positions

In the regression analysis of safety management, which is a dental treatment, the F statistic is 3.292, the significance probability for casual contact in refreshment areas and by conversation was.002, which significantly explains that position and contact in refreshment areas at a significance level of .05 (t=3.152, p=). The position, refreshment area conversation factors are 002, which is explained as 0.077% of the total change (according to the correction factor, 0.054%) (Table 7) [19].

Table 7:Dental care safety management: wearing masks, sharing refreshments and conversations, hand hygiene, washing with work clothes, monitoring infected employees and regression analysis for their positions---(n=203).

Conclusion

Urgent action was required because dental clinics, which account for the majority of dental medical institutions, were very insufficiently equipped to deal with the problem of covid cross infection. In order to properly implement infection control, evidence-oriented regulations or guidelines must be followed. Among university and general hospital dentistry institutions, 97.1%,82.9% followed infection guidelines; 59.5% of dental clinics, similar to the 94.4% at universities and general hospitals did so. Results such as Kwon [20] and Lee [21] showed 85.0- 92.9% at dental clinics, and 44.7-56.0% at other dental clinics. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [22] said that designating infection control personnel and actively operating programs reduced medical infections by 32%, and otherwise increased infection safety by 18%. In Korea, infection management has regulations [23] and the level of infection safety practices increases [24] corresponding to educational experience. Therefore, in order to realize medical infection management, it is necessary to establish a management system. The purpose of the mutual disclosure of confirmed coronavirus patients is not to prohibit going to the dental clinics, but to make sure that those who have contacted COVID-19 or those who use dental areas are careful of contact with others and are more aware of their condition [25]. In this study, the general characteristics of 203 subjects 56, 24.6% were males; 147, 64.5% were females; and the mean and standard deviation was 1.783 (6.638). In terms of experience, the average and standard deviation are 1.881 (1.027) for 80 people having under 2 years, 41.5% for 96 people having under 4 years, 5.3% for 12 people under 6 years, 1.8% for 4 people under 8 years, and 5.3% for 12 people having under 10 years’ experience.

By position there were 31, 13.6% nursing assistants; 17, 7.5% coordinators; 32, 14.0% dental hygienists; 10, 44.3% dental access officials; and 22, 8.6% dentists. The average and standard deviation is 3.325 (1.235). And from the experience of those contacting a confirmed COVID-19 patient, and those with no contact the average and standard deviation was 3.758 (1.405) with 11.0% for six people, 8.8% for two people, 22.8% for three people, and 37.7% for 86 people having four times contact (Table 1). The number of contacts with COVID-19 confirmed patients continues to increase. Dental clinics are contaminated with a large amounts of aerosols and dust generated by intra-oral surgery and scaling, so they should be partitioned in consideration of medical routes for contamination, and the environment and facilities should be managed with cleaning and ventilation. First of all, the combined score of air quality management was similar to 77.2 points and 76.1 points for dental hospitals and universities and general hospitals, and 61.1 points for dental clinics. The main factor of hospital infection is indoor air, and air pollution is proportional to the level of infection [26]. From the design of the structure of the clinics in this study, the concept of infection prevention should be applied, with 73.2% of dental hospitals, 57.1% of dental clinics, and 30.6% of dental clinics making some response.

In this study, a response sample of air infection control by gender and occupation In t-test, the average and standard deviation of contact experiences between position and confirmed coronavirus patients is -.433 (1.823), t=-3.387p value is 0.01, which is a significant level. Take note at 05. The mean and standard deviation of position and infection prevention movement design were -1.039 (1.475), and the t=-10.038 p value was 0.00, which was significant at the significance level of 0.05. The mean and standard deviation of gender and clinic ventilation are -2.551 (1.024), t= -35.471p value is 0.00 and is significant at the significance level of 0.05. The mean and standard deviation in gender and post-treatment disinfection is -2.433 (1.193), t = -29.045, p value is 0.00 and significance level is 05. These show a significant result of 05 (Table 2). In the result of cross-analysis for automatic infection control according to position: for dental clinic air infection, dental attendance officials were the most predominant with 57 people 56.4% answering “It is quite needed”; these were followed by dental hygienists with 16 people, 50% saying “It is quite needed,” and then nursing assistants at 45.2%, 14 people saying “It is quite needed” (Table 3).

In addition, in this study (Table 4) dental room air infection: In the cross-analysis results for ventilation and clinic position, dental attendance officials,53 (52.5%) answered it’s quite needed; and dental hygienists, 15 (46.9%), and nursing assistants, 48.4% also answered it’s quite needed. Throughout the dental profession, the responses showed a 5.5% ratio of 11 people who answered either it’s not needed very much, or I don’t think it’s needed. As a result of cross-analysis to find out whether there is a significant difference in automatic design of infection control by position, there was no significant difference in automatic design of infection control by position at the significance level of .05 with x2 = 9.923a and a significance probability of .871 (Table 5). In the results for post-treatment disinfection and cross-analysis of dental clinic air infection: post-treatment disinfection and position: dental attendance officials, 53 people, 52.5% were the most predominant; followed by dental hygienists, 14, 43.8% who answered it’s quite needed. Throughout the dental profession, the responses show a 9.3% ratio of 19 people who answered either it’s not needed very much, or I don’t think it’s needed. As a result of cross-analysis to find out whether there is a significant difference between posttreatment disinfection and position, there was no significant difference between post-treatment disinfection and occupation at the significance level of .05 with x2 = 14.526a with a significance probability of .560. In addition, surfaces such as bracket tables, switches, and lamp handle in unit chairs can cause contact infections, but they are difficult to clean, so should be disinfected or have protective covers which can be removed after each patient’s care [26].

71.4 to 91.4% of dentists at universities and general hospitals were using approved disinfectants after each patient’s treatment, but only 34.3% of them managed replacing protective covers after each patient’s use, and only 24.0% of dentists were consistent in applying infection safeguards. Pitch management is expected to reflect the overall surface management level, and in fact, there was a high correlation between the surface contamination of the ball and the bacterial contamination of handpiece water [27]. Therefore, it is necessary to guide practitioners on proper surface management methods and suitable procedures for reuse of each piece of equipment characteristic to their own details. In this study (Table 6), the correlation analysis between facility management and position in the clinic showed a high correlation of 617 for ball washing and disinfection after treatment. Subsequently, surface management and position after treatment are shown in the order of .155, and there is a low correlation between surface management and physical distance .021. Medical personnel must wear thorough hand hygiene and personal protective equipment to protect patients and themselves from potential infection risks. Hand hygiene education was practiced in 91.4% of dental clinics in universities and general hospitals, higher than 78.0% of dental hospitals and 50.4% of dental clinics. However, in the practice category, there was no difference by institutional type, 72.7 to 85.7%, which differed from the results of Kim [28] who reported the effect of hand hygiene education.

In the comprehensive medical-related measures of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the possibility of infection due to reuse of medical devices, improper disinfection and sterilization, and insufficient management and use of equipment was pointed out as problems. In particular, dental instruments are frequently exposed to the patient’s body fluids and respiratory secretions during the treatment process, so sterilization is recommended rather than disinfection [28]. In the regression analysis of safety management, which is the dental treatment of this study, the F statistical value was 3.292, the significance probability of refreshment and conversation .002, which significantly explained position and refreshment area use at the significance level of .05 (t=3.152, p=).002) for position refreshment area use the conversation is explained by a total change of 0.077% (according to the correction factor of 0.054%) (Table 7). In addition, complex infection management of environments and facilities such as air and surface management, and suitable operating rooms procedures, should be implemented to prevent infection throughout COVID-19 infection control within dental treatment.

In addition, a thorough sterilization management system should be applied for the use of safe instruments, and medical waste and laundry should be properly disposed of to prevent leakage of medical infections to the outside. Dental personnel should perform hand hygiene and wear personal protective gear when treating both patients and practitioners in order to protect against all of these infection risk factors. The significance of this study is to investigate the infection control system and implementation status of dental institutions by gender, occupation, position, and infection control levels of COVID-19 confirmed patients. The limitations of this study were that domestic studies were conducted on dental workers at dental institutions that were limited to some regions, and the relationship between infection control status in certain areas were affected by limited recognition and performance of infection control recommendations, along with the effect of education. Therefore, it was limited to grasp the overall infection control status and find specific problem areas to take fundamental measures. Future follow-up studies will be conducted on dental workers at dental institutions nationwide to prevent infection throughout COVID-19 infection management and dental treatment.

Discussion

This study conducted a study on 203 dental workers working at Y Dental Clinic, I Dental Clinic, H Dental Clinic, and S Dental Hospital in Gwangju Metropolitan City from April 1 to April 30, 2022, and dental technicians, dental technicians, and dental office workers. Subjects who understood the purpose of the study and agreed to participate in the study conducted and analyzed a selffill questionnaire. The purpose of this study is to identify dental infection control by gender, automatically design dental room infection controls, ventilate the clinic, disinfect work areas after treatment, find causes of cross infection, and use appropriate dental safety management for masks, refreshment and conversation areas, hand hygiene, laundry, and medical care.

a) In the general characteristics of 203 subjects, 56, 24.6% were men, women, 147, 64.5% were women. The average and standard deviation is 1.783(6.638); 80 people had 2 years of experience; 4 people had 4 years of experience; 41.5% had 4 years of experience; 5.3% had 6 years of experience; and 3.8% had 10 years of experience. The average and standard deviation is 1.881(1.027) By position, 31, 13.6% were nursing assistants; 17, 7.5% were coordinators; 32, 14.0% were dental hygienists; 10, 44.3% were dental attendance officials; 22, 8.6% were dentists, with the average and standard deviation being 3.325 (1.235). And in characteristics by experience of contact with confirmed covid patients: 26, 11.0% had no cases of contact with confirmed patients; 20, 8.8% had contact with confirmed patients the first time; 20, 8.8% had contact with confirmed patients the second time; 52, 22.8% had contact the third time: 86, 37.7% had contact with confirmed patients the fourth time. The mean and standard deviation was 3.758 (1.405) (Table 1).

b) In the air infection control response sample t-test by gender and occupation, the average and standard deviation of the contact experience between dental position and confirmed covid patients in Response 1 is -.433 (1.823), t=-3.387p value is 0.01, which is a significant level. Note at 05 In Response 2, the mean and standard deviation by position and infection prevention movement design were -1.039 (1.475), and the t=- 10.038 p value was 0.00, which was significant at a significance level of 0.05. The gender of Response 2 and the mean and standard deviation of the treatment room ventilation were -2.551 (1.024), t= -35.471p values were 0.00 and are significant at the significance level of 0.05. Response 4 Gender and the mean and standard deviation in post-treatment disinfection were -2.433 (1.193), t = -29.045, p value is 0.00 and significance level was .05 These showed a significant result at 05 (Table 2).

c) (Table 3) In the results for cross-analysis of automatic infection control according to position: For dental clinic air infection, dental attendance officials were the most predominant with 57 people 56.4%; these were followed by dental hygienists with 16 people at 50.0%; and then nursing assistants at 45.2%. These responses show a 2.5% ratio of 5 people who answered it’s not needed very much, or I don’t think it’s needed. As a result of cross-analysis to find out if there is a significant difference in the automatic design for infection control by position, there was no significant difference in the automatic design for infection control by position at the significance level of .05 with x2 = 16.960a and a significance probability of .388.

d) (Table 4) Dental room air infection: In the cross-analysis results for ventilation and clinic position, dental attendance officials,53 (52.5%) answered it’s quite needed; and dental hygienists, 15 (46.9%), and nursing assistants, 48.4% also answered it’s quite needed. Throughout the dental profession, the responses showed a 5.5% ratio of 11 people who answered either it’s not needed very much, or I don’t think it’s needed. As a result of cross-analysis to find out if there is a significant difference in the automatic design of infection control by position, there was no significant difference in the automatic design of infection control by position at the significance level of .05 with x2 = 9.923a and a significance probability of .871.

e) (Table 5) In the results for post-treatment disinfection and cross-analysis of dental clinic air infection: post-treatment disinfection and position: dental attendance officials, 52.5% were the most predominant; followed by dental hygienists, 14, 43.8% who answered it’s quite needed. Throughout the dental profession, the responses show a 9.3% ratio of 19 people who answered either it’s not needed very much, or I don’t think it’s needed. As a result of cross-analysis to find out whether there is a significant difference between post-treatment disinfection and position, x2 = 14.526a with a significance probability of .560.

f) In (Table 6) in the analysis of the correlation between facility management and position in the clinic, the posttreatment ball washing, and disinfection is 617, showing a high correlation. Subsequently, surface management and position after treatment are shown in the order of .155, and there is a low correlation between surface management and physical distance .021.

g) In the regression analysis of safety management, which is a dental treatment, the F statistic is 3.292, the significance probability for casual contact in refreshment areas and by conversation was.002, which significantly explains that position and contact in refreshment areas at a significance level of .05 (t=3.152, p=.002), refreshment area and conversations by positions are explained as 0.077% of the total change (according to the correction factor, 0.054%) (Table 7).

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. The cost of posting online papers is paid by the author.

References

- Moon HS (1992) A Study on the Health of Dentists. Journal of the Korean Oral Health Association 16(1): 53- 73.

- You SM (2013) Knowledge, Attitude, and Performance of Handwashing by Health University Students. Journal of the Korean Society of Industrial Technology 14(8): 3916-3924.

- (2022) Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's standard prevention guidelines for infection prevention and management of COVID-19 in dental medical institutions.

- (2013) Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation: Dental hospital accreditation standard. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Seoul, pp.107-117.

- (2020) The National Health Insurance Corporation Hospital Information.

- Kohn WG, Harte JA, Malvitz DM (2004) Guidelines for infection control in dental health care settings-2003. J Am Dent Assoc 13(5): 3-47.

- (2006) Ministry of Health and Welfare. Dental treatment Prevention of Infection Korea.

- Chung HJ, Lee JH (2015) Factors influencing the perception and practice of infection control by dental hygienists in some areas. Journal of the Korean Dental Hygiene Society 15(3): 363-369.

- LEE YH, Choi SM (2015) Awareness and Practice Survey of Dental Infection Management by Type of Workplace. Journal of the Korean Society of Radiology 9(6): 409-416.

- Jeon JS, Choi SM, Lee YH (2018) A Comparative Study On The Perception And Practice Of Infection Control By Dental Hygienists Multi-Media Paper On The Convergence Of Art And Humanities Society 8(12): 597-606.

- (2022) Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Korean Medical Association for the Prevention of Infection Standards.

- (2008) Ministry of Environment, Medical Waste Management System Guide, Republic of Korea.

- (2020) National Legal Information Center. Article 2, 5 of the Waste Management Act, Republic of Korea.

- (1999) American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Dental unit waterlines: approaching the year 2000. ADA Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc 130(11): 1653-1664.

- Lee SS, Kim DY, Song SY (2016) Perception and practice of dental hygienists on the maintenance of dental units. Journal of the Korean Dental Hygiene Society 16(4): 507-516.

- (2017) Ministry of Health and Welfare Revision of Guidelines for Disinfection of Equipment and Articles for Use of Medical Institutions, Republic of Korea.

- Son EK, Choi UY, Jung HY (2016) Survey on the management of uniforms by dental hygienists. Survey on uniform management by Son, Choi Woo-yang, Jeong Hwa-young, and other dental hygienists. Survey on uniform management by Son, Choi Woo-yang, Jeong Hwa-young, and other dental hygienists. Journal of the Korean Dental Hygiene Society 16(4): 517-523.

- Walker TS, Tomlin KL, Worthen GS, Poch KR, Lieber JG, et al. (2005) Enhanced Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development mediated by human neutrophils. Infect Immunity 73: 3693-3701.

- Kwon SJ (2014) Development of evaluation indicator for dental hospital accreditation. Busan Univ of Kosin, Korea.

- Jeong HJ, Lee JH (2016) A survey on infection control status of the dental care institution. AJMAHS 6(6): 51-58.

- (1985) Hospital infection control recent progress and opportunities under prospective payment. Am J Infect Control 13(3): 97-108.

- Jeong HJ, Lee JH (2016) A survey on infection control status of the dental care institution. AJMAHS 6(6): 51-58.

- Nam YS, Yoo JS, Park MS (2007) A study on actual conditions for prevention of infections by dental hygienists. J Den Hyg Sci 7(1): 1-7.

- Min DW (2020) The effect of ambiguity of information on Covid-19 patients’ contact trace on intention to visit the commercial district: Comparison of residents in Gangnam-gu and Seocho-gu Associate Professor, Journal of Digital Convergence 18(8): 179-184.

- (2017) Korean Society for Healthcare-associated Infection Control and Prevention. Standard preventive guidelines for medical-related infections Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

- Yun KO, Park HJ, Son BS (2014) A study on bacterial concentrations in dental offices. Journal of Environmental Health Sciences 40(6): 469-476.

- Kim EG (2017) The development and effect of the education program on hand hygiene and use of personal protective equipment. International Journal of Infection Control 15(4).

- (2018) Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Institute for Healthcare Accredition. Dental hospital certification standards.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...