Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Dental Home Prevalence Among Children with Medicaid in the Bronx, New York Volume 5 - Issue 2

Nadia Laniado*

- Department of Dentistry, Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Jacobi Medical Center, USA

Received: December 02, 2020; Published: December 14, 2020

*Corresponding author:Nadia Laniado DDS, MPH, MSc, Department of Dentistry, Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Jacobi Medical Center, 1400 Pelham Parkway South Bronx, New York, USA

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2020.05.000209

Abstract

The successful management of patients with cleft lip and palate deformity requires a multidisciplinary approach. Historically, cleft lip and palate care starts with treatment modality of presurgical infant orthopaedics (PSIO). However, the necessity of presurgical orthopaedics in managing the resulting orofacial deformity is the discussion to ponder upon due to the variety of methodologies available and results produced by these devices. The objectives of this paper were to review the journey of PSIO appliances so far, basic principles of PSIO treatment, the various types of techniques and the protocol followed, and to critically appraise the advantages and disadvantages of these techniques. In conclusion, we believe that PSO treatment, with its objective to approximate the segments of the cleft maxilla may reduce the intersegment space in readiness for the surgical closure of cleft sites.

Keywords: Cleft lip and palate; presurgical infant orthopaedics; PSIO

Abbreviations: PSIO: Presurgical Infant Orthopaedics; CLP: Cleft Lip and Palate; NAM: Nasoalveolar Molding; DMA: Dentomaxillary Advancement Appliance; UCLP: Unilateral Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate

Introduction

The concept of a ‘dental home’ is analogous to the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) concept of a ‘medical home.’ The national guidelines of both the AAP and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry recommend that children have a dental visit by 12 months of age and receive preventive care at regular intervals thereafter [1]. Dental caries remains the most common chronic disease of childhood, and early childhood caries (decay among children less than six years) disproportionately affects children of low socioeconomic status [2]. The establishment of a dental home early in a child’s life is crucial to providing continuous and family-centered preventive dental care and mitigates the consequences of poor oral health such as pain, missed school days, and emergency department visits [3]. In this study we assessed the prevalence of a dental home among children with Medicaid benefits, ages 1-17 years, presenting for their well-child medical visit. To our knowledge, we are unaware of any studies that have presented prevalence estimates for age at dental home establishment among children with Medicaid benefits.

Methods

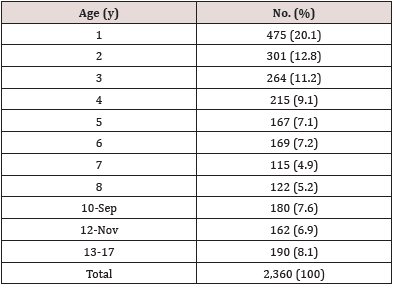

Our sample consisted of 2,360 children ages 12 months to 17 years who presented for their well-child visit at the Pediatric Primary Care Clinic at Jacobi Medical Center (JMC) in the Bronx, New York from January 2016 to June 2020. JMC is one of eleven safety net hospitals in New York City’s municipal hospital system serving a predominantly Hispanic/Latino and African American population. This observational study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Jacobi Medical Center and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. As part of an interprofessional dental training program, pediatric dental residents provided dental screenings, risk assessment (AAP Oral Health Risk Assessment Tool), [4] and fluoride application in the pediatric medical clinic. The prevalence of a dental home at each age was calculated. Children making multiple visits were counted only once, resulting in a patient count rather than a visit count. All participants were Medicaid-eligible. Data analysis was conducted using Stata version 15.1 (Stata Corp) (Table 1).

Results

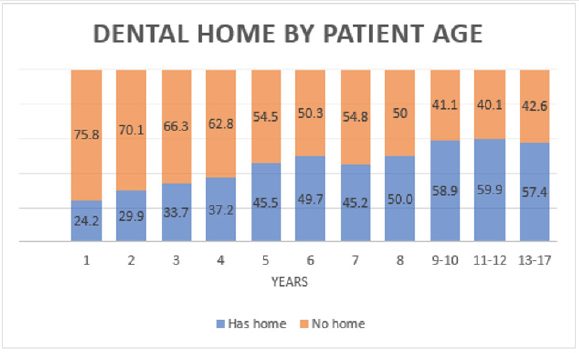

Of the 2,360 children in this study, one-year-olds accounted for 20.1 percent of the sample and by this age 24.2 percent had a dental home. Children six years and younger accounted for 68 percent of the sample and by six years 49.7 percent had a dental home. Among teenagers 13-17 years old, 57 percent had an established dental home.

Discussion

The age distribution of our sample is consistent with national pediatric visit data and our analysis supports studies that have demonstrated that despite professional recommendations, significant gaps remain in the establishment of dental homes by age one for Medicaid-eligible children [5,6]. Although an upward trend is observed in the pre-school years among children with Medicaid, over 50 percent do not have a dental home by age six thereby missing a crucial opportunity for oral health education, anticipatory guidance, and preventive services during their growth and development. Among older children and adolescents, there is a plateau in establishment of a dental home at approximately 57 percent leaving many teenagers to rely on emergency departments for palliative care (Figure 1). Despite limited generalizability to a pediatric Medicaid population in the Bronx, the results of this study indicate that there is an urgent need for greater efforts and strategies to improve interprofessional education, care coordination, and dental referrals. Given that there are approximately ten well-child medical visits during the first two years of life, there is a unique opportunity for pediatric medical practitioners to provide oral health counseling and make timely referrals in order to establish a dental home by age one and end the epidemic of childhood decay among poor children.

Funding/Support:

This research was supported by Health Resources and Service Administration grant D88HP28502.

References

- Kevin JH (2013) American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Pediatric Dentistry. Oral health risk assessment timing and establishment of the dental home. Pediatrics 111(5): 1113-1116.

- Dye BA, Mitnik GL, Iafolla TJ, Vargas CM (2017) Trends in dental caries in children and adolescents according to poverty status in the United States from 1999 through 2004 and from 2011 through 2014. J Am Dent Assoc 148(8): 550-565.

- Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS (2002) The dental home: a primary care oral health concept. J Am Dent Assoc 133(1): 93-98.

- Douglass JM, Clark MB (2015) Integrating oral health into overall health care to prevent early childhood caries: need, evidence, and solutions. Pediatric Dentistry 37(3): 266-274.

- (2010) American Academy of Pediatrics: Profile of Pediatric Visits. Elk Grove Village, American Academy of Pediatrics, IL, USA.

- Hakim RB, Babish JD, Davis AC (2012) State of dental care among Medicaid-enrolled children in the United States. Pediatrics130(1): 5-14.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...