Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6679

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-6679)

The Health Service in Great Britain

a Comparison with

The Swiss Health System

Volume 4 - Issue 2

Stephanie Looser*

- University of Surrey, Centre for Environmental Strategy, UK

Received: October 14, 2019; Published: November 07, 2019

Corresponding author: Stephanie Looser, University of Surrey, Centre for Environmental Strategy, UK

DOI: 10.32474/RRHOAJ.2019.04.000183

Abstract

Regarding research and reviews on healthcare, international comparisons are striking, since they could manifest different levels’ performances of healthcare systems. This research, for instance, analyses two set-ups: the British vs. the health service of Switzerland. On the one hand, it shows the Swiss system’s “bad” performance due to its cost extensity. Compared to many OECD countries, particularly regarding the United Kingdom’s (UK) system, the latter seems to leave a better impression. This paper explores the structural and organizational set-up of both countries’ health care. This is based on concrete data from “The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development” (OECD) and from “The World Health Organization” (WHO) and, thus, shows the both countries’ differences and similarities. To be mentioned, the fact of incomplete or not available data regarding fundamental and cost-relevant data from the Swiss system brought about some methodical problems.

Keywords: British National Healthcare System; NHS; Healthcare In Switzerland; International Comparison

Introduction

In Britain, the key issue is to a considerably larger extent financially intended caused by a savage rationalization. Certainly, a cost-saving measure, however, on the other hand causing great injustice and suffering. This raises the question of whether an international comparison – e.g., the annual WHO and the OECD OECD [1] ones – might only be based on costs and figures, or whether the hard-to-find health of the population in the respective health care should be more significant in evaluations? Over all, seen from a purely statistical point of view: A “cheap” healthcare system that does not count older and/or more expensive patients (e.g., due to inadequate care and/or death) is not representative, objective, reliable, nor internal/external variability. Nowadays, the British ideal of providing the same HEALTH treatment to all residents (see Section 5) – or in other words “the rich patient dies next to the poor” – is still ways beyond. However, on the one hand it is quite praiseworthy, nevertheless, it still pretends to example the mentioned ideal, e.g., as a rich patient cannot buy any cure by expensive drugs. Section 2 introduces some overarching theoretical aspects regarding healthcare, while Sec-tion 3 shortly comes up with the methodological approach, so to describe the British and the Swiss healthcare systems in Sections 4 and 5. Thus, Section 6 compares both set-ups re-garding specific aspects, depending on reliable and available data. – considering different oth-er countries, in order to get a broader vantage point. Lastly, Section 7 is concluding about, e.g., the relation, or even correlation/causality, between the health care’s gross domestic product proportion and its quality, etc.

Theory: Two Poles of Responsibility and the Pentagon of Goals

Responsibility in regard of healthiness (and/or sickness) largely depends on market systems. Though, this seems to be, on a first glance, quite antithetic or at least inconsistent and/or contractionary, a detailed analysis shows some dependencies.

Marked Oriented Economic Systems are Sharply Tied to Competition

Thus, the individual is affected, impacted, and in the case not used to, also discon-certed. However, these systems ask for selfresponsibility and decisiveness between competitors. Particularly, regarding healthcare, this might include insurance compa-nies, hospitals, managed care systems, even chosen practitioners, specialists, ex-perts, etc.

Public Steered Systems Rely on Social, Societal, and / or Cooperative Respon-Sibility

In daily business, this works, if social cohesion was highvalued, the state took over lots of responsibilities, and/or society is cooperatively well organised regarding healthcare and/or other issues. These are the two poles by witch systems are in most cases, and from a bottom-up ap-proach, oriented and organized. Additionally, health care systems’ measures are determined by the general population’s health, addressing issues, such as:

a) Self-Determination.

b) Privacy.

c) Customer Focus.

d) Dignity, And.

e) Equitably Financial Distribution Who, [2] Financial

Times[3].

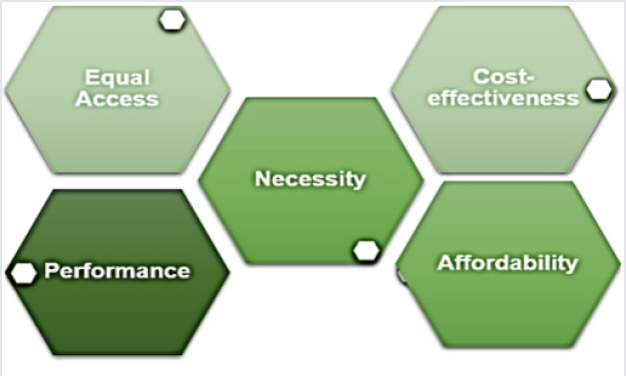

Further, healthcare’s scientific quality-characteristics provide diverging criterions, as well, however, seen from another vantage point. Generally, according to (Figure 1), they are measured by equal accessing opportunities, per-formance (e.g., rapid and effective treatment), treatment’s necessity (i.e., deterred by finan-cial and/ or lobbying power), cost-effectiveness (i.e., cost-benefit ratio), and affordability (Kocher and Oggier)[4].

Methodology

The aim of this work was to compare the structure, structure and organization of health care in the United Kingdom with those of the Swiss healthcare system. One of the main attempts was, not to lose sight of the perspective and needs of a patient in the respective healthcare system. In this aspect, the methodology is based on a broad global literature review. In the first instance, the search was carried out nationally on the side of Swissbib [5]. Swissbib brings together 900 Swiss libraries, media libraries and archives and includes 19 million doc-uments Swissbib [5]. Regarding historical sources, in a second step, the catalogues of the University of Economics of Munich (2018) and the University of Mannheim (2018) were also included Financial Times [3]. In a third step, the search was extended to the whole of Europe. Here, the focus was on Eng-lish-language literature, so the search continued in the online catalogue of the University of Oxford and the Cambridge Digital Library. Finally, the three currently most prestigious US universities have joined the circle: Massachu-setts Institute of Technology (MIT), Harvard University and Yale University. These three uni-versities ranked first, third, and seventh in the QS Star University ranking in 2012, the Univer-sity of Cambridge in second, and the University of Oxford fifth (QS). This considered five of the world’s seven highest ranked research universities. Further, the gathered data was triangulated with currently accurate figures from the World Health Organization (WHO) statistics and the statistics provided by the countries of the Or-ganization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Five researchers coded the texts using MAXQDA and the overall inter-rater reliability was 0.89 (calculated by the Holsti formula Rössler [6]. Thus, the details’ necessary depth, regarding capabilities and costs of the two systems, apart from objectivity, reliability, as well as internal/external validity, showed consistency.

A Social Security System: The Health Service of Switzerland

Swiss federalism dominates, as many other issues, also the set-up of diverging Swiss health care systems. This has led to a somewhat confusing fragmentation of various types of insur-ances Kocher and Oggier [4]. In the following, this complexity is tried to be defined, vari-ous problems addressed, and the fragmentation’s complexity should be explained in more detail. Firstly, Switzerland’s social security system includes:

a) Health Insurance.

b) Accident Insurance.

c) Disability Insurance.

d) Military Insurance; And

e) Maternity Insurance.

This splitting often leads to either double benefits of some individuals, or difficulties in defining risks, and might be one of the key reasons, why the Swiss healthcare system is (regarding global comparison) that much expensive Kocher and Oggier [4]. Swiss health insurance companies are privately organised. Thus, there is no public health insurance Kocher and Oggier [4], nevertheless every Swiss resident must be insured – this includes minors, whose responsibility is, in most cases, filled by their legal representative) Kocher and Oggier, [4]. Social health insurance includes compulsory health care as well voluntary daily allowance insurance Kocher and Oggier [4]. Further, it covers illness, ma-ternity as well as subsidiary accidents. Compulsory basic insurance (i.e., illness, etc.) is regulated by Swiss law and obliges health insurers to fulfil these official tasks Kocher and Oggier [4]. Obligatory and unitary premiums – there are no levels of premium based on risk or income – is meant to create solidarity between the healthy and the ill Kocher and Oggier [4]. This aspect of creating social soli-darity between financially indifferent individua, by reducing premiums individually adjusted to economic performance and financed by tax revenues, is the main key of the Swiss social security system Kocher and Oggier [4]. Nevertheless, by this measure, the Swiss insur-ance system depends, by its bottom, on income (vernunft-schweiz). Compulsory, in other words, basic insurance – in contrast to supplementary insurance – is provided to every citizen Kocher and Oggier [4]. Regarding the entire population’s official security/duty to hold basic insurance, e.g., accession control and the inability to switch insur-ers without confirming the new insurer, are implemented measures Kocher and Oggier [4]. Health insurance companies, in turn, are under obligation to provide basic insurance to any applying and in the area of the company domiciled citizen (vernunftschweiz). Howev-er, beforehand the former pays any health costs, each of the latter pays at least an annual premium of CHF 300 and usually a 10 percent deduction on any benefit (vernunft-schweiz). In addition, Swiss private insurers could provide supplement services, apart from ob-ligatory basic ones Kocher and Oggier [4]. By governmental acting as chaperons, the Swiss system, by contrast to other European countries, prevent the withdrawal from compulsory health insurance by choosing a private competitor Kocher and Oggier [4].

Qualitative Assessments of the Swiss Health System

In fact, by WHO assessment, Switzerland ranked 20th out of 191 members WHO [2]. As the decisive factor regarding the WHO evaluation is the cost-level. Contrasting:

a) Fair System Accessing.

b) Population’s Self-Determination.

c) Responding To The Latter’s Needs.

d) Treating Older Population In Dignified Manner.

Place the Swiss health care system on a very diverging level. International comparisons show a correlation – though, not causality – between high proportions of patients AND a poor health system. As poor medical care could cause quick deaths, these fall out of the data collection. However, in a well-functioning health system country (e.g., Switzerland), these individuals are statistically seen a cost factor.

Healthcare in the UK

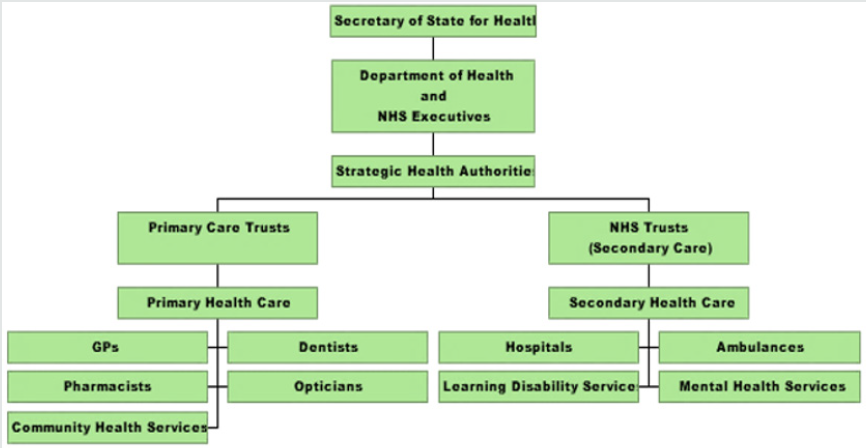

There is no statutory health insurance in United Kingdom (UK) – unlike the Swiss system. Instead, medical care is provided under the 1948 National Health Service (NHS), a state-owned and mostly tax-funded health care system. NHS provides medical benefits to all UK residents regardless of their income, insurance-status, contributions, nationality, or any other conditions Kaufmann[7]. In the comprehensive NHS system, general and specialist treatments as well as out- and inpatient care are included Gethmann et al. [8]. Dental and ophthalmological care, accommodations in care facilities, rehabilitation measures, and the supply of medicines, etc. are NHS included services Gethmann et al. [8] . General practitioners (GP) treat patients, however, there is no direct access to specialists and hospitals Kaufmann [7]. Thus, UK health care is based on a, so-called, “gatekeeper prin-ciple”. GPs act as patients’ first point of contact, as case-manager by accompanying the pa-tients throughout the disease process and submitting them to the appropriate healthcare pro-vider and/or referring specialist Gethmann et al. [8]. (Figure 2) represents the NHS’ organisational overview: The complexity of UK fundraising is lower compared to the Swiss set-up. UK public health budget is taxed, and, thus, the main source of Tax “funding” NHS [9]. In 2018, UK public healthcare’s funding was 78% NHS [9]. The UK utilities are predominantly state-owned Gethmann et al. [8]. To promote commu-nity practice is one of the GPs’ key tasks (e.g., 75%), which is governmentally granted Gethmann et al. [8]. To get access to a Specialist’s work – in contrast to Switzerland – is possible in hospitals only NHS[9].

The national health service’s financial system

Since its inception, the NHS has been largely funded by general tax revenues, as already mentioned (Missoc-Info [10] . These tax revenues also include income-related social securi-ty contributions (National Insurance Contributions NICs) paid by workers and employers Mis-soc-Info,[10]. UK is also facing a striking decuple cost increase since its inception (e.g., 1948, £ 9 billion were enough). Nowadays, the NHS budget is round about £ 90 NHS [11]. In other words, approximately £ 1500 per person was available at 2007/2008 NHS [12]. 80% of the total budget was/is distributed directly by local trusts equal local needs (NHS). Higher level health authorities (e.g., The Primary Care Trust) is reliable regarding: e.g., capacity planning according to regional needs and available resources NHS [9]. In order to determine this medical need, socalled, health improvement plans, were set up, which serve as a basis for capacity planning Gethmann et al. [8]. These plans define the necessary range of services and investment volume Gethmann et al. [8]. Yet, 60% of the budget is spent on £ million 1.5 NHS dedicated to staff compensation em-ploying more than 1.5 million people, making it the fourth largest employer in the world NHS [12]. Another 20% is spent on medicines and other medical products (NHS [11]. Thus, only 20% of the budget could be spent on e.g., preservation of facilities and equipment, as well as for food and cleaning NHS [12].

A british patient’s life: a case study

The following case study addresses shortcomings of the British health system. 250’000 British people are suffering from the “wet” variant of old-age blindness (i.e., wet macular degenera-tion), whose effective and successful treatment by a specific drug fails. The drug is seemingly to expensive–a decision taken by NHS London [13]. An unblinded eye does not count following the regulation: “Drugs have to be cheap, permanently effective, with a short life ex-tension”. NICE (i.e., the drug regulation institution, aligned with NHS) has not generally ap-proved the mentioned drug (i.e., Novartis Lucentis), thus, thousands of Englishmen suffer from blindness London [13]. Because individual local authorities grant treatments, it further depends on where exactly indi-viduals live (e.g., in England or Wales). As the reason for the manifestation as well as NHS’ ideal is “to treat all citizens equally well” (NHS), such cases demonstrate an evident contradiction. Thus, this unequal treatment ended up in court London [13]. The result: A treatment with “Lucentis” might be possible under the conditions that both eyes must be af-fected, however only one eye’s treatment will be paid. NICE’s rigid and unclear cost control has already claimed countless victims Glasby [14]. Other disputes include drugs for effective cancer treatment, further drugs to treat first stirrings in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease London, [13]. Since one runs the risk of not receiving lifesaving medicines against, e.g., cancer or Parkinson’s, anyone, who can afford it, pays for an expensive supplementary private health insurance (London, 2008). To prevent a two-class system, NICE has prohibited patients to have unapproved, however, self-paid medicines administered by state doctors London [13]. To sum up, NHS enjoys a world-wide reputation regarding the treatment of quite specific and/or complicated illnesses Glasby[14]. However, regarding routine treatments it seems to be in bad odour.

Differences Between the British and Thee Swiss Health Systems

After having presented the health systems of Switzerland and Great Britain, the concrete dif-ferences are the following:

a) Different Costs.

b) Different Service Catalogues.

c) Differences In Efficiency.

d) Differences In Affordability.

e) Diverging Levels Of Digitization In Health Care.

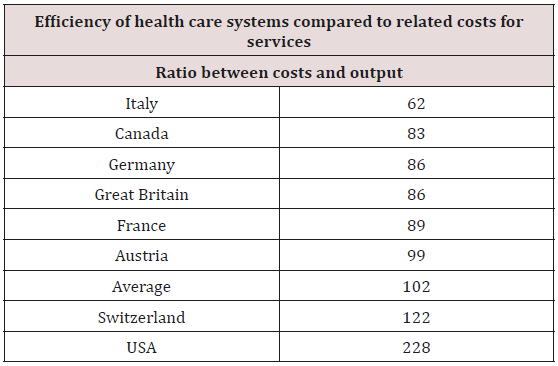

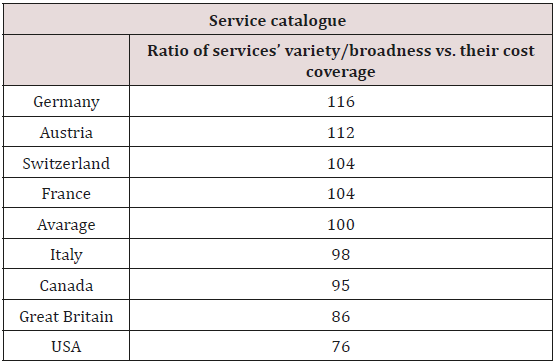

Regarding “efficiency” (Table 1) research came up with the following data. To exclude any misunderstanding, these are not data provided by the insurer (though this should have been the case).

Differences Regarding Efficiency

The ratio of costs to benefits (i.e., output) determines the efficiency of a health care system see (Table 1); a more accurate picture would give the relation between costs vs. outcome. However, yet, this does not seem to be determinable in an extended international comparison due to lacking data, etc. (Kocher and Oggier, 2007). The Fritz Beske Institute has also carried out an evaluation based on an efficiency formula (Kaufmann, 2018). The average of “102” is the result of the Beske’s formula. In many cases, predominantly tax-financed systems are more efficient compared to contribu-tory ones Kocher and Oggier [4]. As a result, UK scores with 86 very well regarding the average of 102 and the fact: “lower score = more efficient” Kocher and Oggier [4]. However, regarding efficiency data (i.e., depending on exact cost data) from Italy and Cana-da, the Institute acknowledges some potential inaccuracies traced back to theses countries’ insufficient healthcare reporting Switzerland is far beneath average and, after USA, the second most inefficient health system. Expensive healthcare systems – e.g., USA and Switzerland – seem to perform less well re-garding efficiencyrelated issues (i.e., the ratio between costs and output, however, not out-come) Kocher and Oggier [4]. Regarding Gross Domestic Product (GDP), there is one remarkable fact: Germany reports mostly equivalent health care costs (in percentage of GDP) as the USA/Switzerland, never-theless, its efficiency is one of the best performing [15-18].

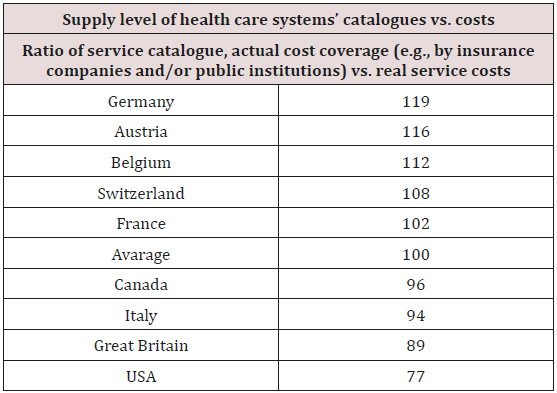

Differences Regarding Output

The performance catalogues regarding health and cash benefits could be compared due to a comprehensive study by Fritz Beske Institute, Kiel Kocher and Oggier [4]. For this purpose, an index – in order to compare the announced catalogue services, (actually) payable supplied services, and the related costs – has been developed. Thus, the healthcare, as well as, related services were deeply analysed see (Table 2). This made it possible to compare the different countries’ service catalogues; where a high value means that the sup-ply level is very good Kaufmann [13]. About the level of healthcare provision (i.e., average value of the “care index” = 100) Switzer-land ranks fourth (i.e., 108), behind Germany, Austria and Belgium Kocher and Oggier [4]. By comparison, UK has a lower score on health outcomes (i.e., 89) Kocher and Oggier [4]. (Table 3) shows the comprehensiveness of the service catalogue. In other words, it is a sum-mary of services a patient is provided with and payments that are covered (e.g., by insurance companies and/or public institutions). Thus, for instance [19-22], Germany provides the most extensive service catalogue that is at the same time covered by insurance and/or state. A similar picture appears in the evaluation of the scope of the service catalogues; Switzer-land’s health care system also has an above-average score of 104, which is significantly higher than the value of the United Kingdom, whose health care has a below-average perfor-mance index of 86 Kocher and Oggier 4].

Conclusion

A conclusive comparison between the two health systems in Switzerland and the UK is simply not possible because Switzerland lacks reliable data, especially from Switzerland. Neverthe-less, based on the arguments listed so far, a certain tendency can still be maintained. Namely, a high proportion of gross domestic product does not necessarily correlate with a good quality healthcare system Kocher and Oggier [4], NHS [9]. While Switzerland is good on some aspects, it is never clear what healthcare is doing or where just high payments are good. Although Britain’s system tends to underperform the money and health care supply index, the whole population profits from the same benefits. In addition, neither income nor any degree of employment play a role here. The British system suffers from the unclear admission conditions for medicines and treat-ments; This fact leaves the impression of unjust arbitrariness, as exemplified by the age-blindness and the lack of authorization for the saving drug Lucentis. In Switzerland, on the other hand, there are already some conditions that are almost the same as in the USA, where a generally insured patient is rejected in certain hospitals and the most expensive system is transformed into the most inefficient one Kaufmann [7]. Furthermore, Switzerland is a small territory in size, with high population density, which has been uncontrollable for many years (e.g., due to war-times and, as another example, by the refugees, who overwhelmed Germany). Switzerland provided shelter to anybody, who crossed the German/ Swiss border, healthcare included. As well-being, including the multifactorial biopsychosocial consequences, the state provides healthcare “free of charge” to, e.g., homeless people, refugees, to paupers, etc. Nevertheless, for all other citizens in Switzerland, basic insurance (i.e., illness, etc.) is a compulsory task to be filled/ payed individually regulated by Swiss law. Of concern is the lack of data on quality, the lack of electronic involvement and the critical issues raised by the lack of data on the poor value for money. Thus, each of the two present-ed systems has its clear advantages but also disadvantages. In all political discussions on cost reductions, changes in the benefit catalogues and on a possible social unity fund, the well-being of the patient should always be the highest maxim. However, in times of crises, maxims might be adapted or reelevated.

References

- OECD Health Data (2018c) Current Query: Switzerland.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) (2018) Regional Office for Europe. WHO regional publications, European series. WHO regional publications. WHO, Regional Office for Europe Copenhagen, USA.

- Financial Times (2018) Business education Rankings.

- Kocher G, Oggier W Hrsg (2007) Gesundheitswesen Schweiz 2007-2009. Eine aktuelle Übersicht 3 Auflage Hans Huber Bern.

- Swissbib (2018) Was ist enthalten?

- Rössler P (2005) Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft GmbH.

- Kaufmann FX (2018) Variations of the Welfare State: Great Britain, Sweden, France and Germany Between Capitalism and Socialism. München Springer.

- Gethmann CF (2004) Gesundheit nach Mass ? Eine transdisziplinäre Studie zu den Grundlagen eines Gesundheitssystems. Akademie Verlag Berlin.

- NHS (2019) Provider quality indicators.

- (2002)MISSOC Gegenseitiges Informationssystem der sozialen Sicherheit in den Mitgliedstaaten der EU und des EWR. MISSOC-Info 03/2002. Gesundheitsversorgung in Europa. Vereinigtes Königreich.

- NHS (2018a) About the NHS. Authorities and Trusts.

- NHS (2018b) About the NHS. Regulation.

- London M (2008) Blindheit im englischen Gesundheitswesen. Ein Fallbeispiel grausamer Rationalisierung. Neue Zürcher Zeitung p: 1-7.

- Glasby J (2007) Understanding health and social care. Policy Bristol pp: 1-224.

- Ham C (2004) Health Policy in England: The Politics and Organisation of the National Health Service. print. Palgrave Macmillan Basingstoke.

- NHS (2017) About the NHS. Structure.

- OECD Health Data (2018a) How does the United Kingdom Compare?

- OECD Health Data (2018b) Current Query: United Kingdom.

- QS (2019) 2012 World University Ranking.

- TU München (2013) Historie der Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften.

- Universität Mannheim (2019) Zahlen & Geschichte.

- Vernunft Schweiz (2003) Gesundheitssystem der Schweiz.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...

.png)