Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6679

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-6679)

A Study of Culture Noise Culture Noise Influence on Effective Communication between Health Care Providers and Patients in Ogume, Delta State, Nigeria Volume 2 - Issue 2

Chinenye Nwabueze1* and Emmanuel Odishika2

- 1Department of Mass Communication, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Nigeria

- 2Department of Mass Communication, Novena University, Nigeria

Received: May 23, 2018; Published: May 31, 2018

Corresponding author: Chinenye Nwabueze, Department of Mass Communication, Chukwuemeka, Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria

DOI: 10.32474/RRHOAJ.2018.02.000131

Abstract

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

This research examined the preponderance of culture noise as barrier in the channel of communication between health care providers and patients. The primary objective of the study was to assess how cultural health beliefs influenced the effectiveness of communication between health care providers and patients at the Ogume Primary Health Care Centre in Ndokwa West Local Government Area of Delta State. A total of 134 respondents were purposively selected and studied in this work. The triangulation approach was adopted, using a combination of both survey and in depth interview methods. While the survey method used the instrument of questionnaire for data collection, the in depth interview used the interview guide. The theory of Reasoned Action provided the framework for the study. The results of the study showed that the contrariness in the cultural health beliefs of health care providers and patients negatively influenced the communication between both parties. Hence, majority of the respondents exhibited healthcare-default-behaviours such as non-adherence to doctor’s prescriptions, self-medication and outright resort to traditional medicine therapy. Therefore, the paper recommends, among others, adequate education of health care providers to make them knowledgeable about these cultural health beliefs in rural settings and their significance in achieving effective provider- Patient communication as a precursor to securing patients’ confidence, dependence and adherence to medical instructions.

Introduction

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

This study was inspired by two separate health related incidents the researcher was recently exposed to. One was fatal and the other, which would have been as tragic, was reversed because of timely intervention by medical orthodoxy. The first was the regrettable death of a 40years old, educated mother who died during childbirth at the home of a traditional medicine woman despite medical advice that the baby in her womb was lying bridged. The second was the near blindness of my mother from cataract despite being diagnosed of the problem many years ago by orthodox medical science. While my mother managed her sight problem with dew drops collected from cocoyam leaves culturally believed to be efficacious for such state; the deceased believed the traditional medicine woman possessed the spiritual powers to ward off the malevolent forces purportedly responsible for the bridged state of her pregnancy. Both cases point to the problem of how cultural health beliefs could constitute noise in the channel of communication between health care providers and patients. Perhaps if the message of what needed to be done was effectively communicated in the two cases cited above, the deceased mother would still be alive and my mother would have received timely surgical intervention to correct her sight problem long before now! Health communication is the study and practice of communicating promotional health information, such as in public health campaigns, health education, and between doctor and patients Abroms & Maibach [1]. One of the major purposes of health communication is to inculcate health literacy in patients that will enable them make informed personal health choices. It has been proposed that strong, clear and positive relationships with physicians can radically improve and increase the condition of a patient Noar et al. [2]. This is why Edgar and Hyde [3] recommend interpersonal communication between health care providers and patients as one of the most effective strategies for achieving positive health outcomes in patients. Frank et al. [4] corroborate this position by affirming that effective communication between physicians and their patients has been associated with patient outcomes which, incidentally, is the ultimate goal of the health care providers/patient communication Fong, Anat and Longnecker [5]. Unfortunately, studies have shown that the goal of achieving effective communication between health care providers and their patients has always been beset by a number of barriers one of which is patients’ cultural beliefs Diette & Rand [6]; Tongue et al. [7] Recent consensus in public health and health communication reflects increasing recognition of the important role of culture as a factor associated with health and health behaviours, as well as a potential means of enhancing the effectiveness of health communication programmes and interventions Institute of Medicine, in kreuter and Mc Clure [8].

Africa, in the portrayal of Andrews and Boyles, in Singleton, Elizbeth & Krause [9] belongs to the magico-religious and deterministic groups. While the magico-religious group believes in supernatural forces or evil spirits inflicting people with ailments as punishment for sin or the handiwork of evil ones who cast spells on people; the determinist group believes in the preordainment of ailments and cure. A corollary to this belief system is the extended belief in the power of traditional medicine men and the efficacy of their charms and herbs to reverse the ill-fortune of ill-health. This predisposition and predilection towards cultural health beliefs and traditional medicine as an alternative to orthodox medicine has always constituted a noise element in the effective communication between health care providers and patients in Africa. This feeling is expressed in defaults in medical care such as non-adherence to medical instructions, self medication, procrastinated resort to medical advice and their attendant complications for health outcomes. Interestingly, despite the gloomy scenario painted above, Ojua [10] and Kakung [11], equal believers in the above position, now express the sentiment that development, civilization and education, among other factors, have helped to introduce tremendous change in the beliefs and bahaviour of Africans to orthodox medicine patronage. Is this true? To be certain, it has become imperative that a study be conducted to establish the influence of cultural beliefs on the communication between healthcare providers and the rural dwellers; their compliance with healthcare providers prescriptions; and the health information seeking behaviour they exhibit.

Statement of Problem

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

One of the major purposes of health communication is to inculcate health literacy in patients that will enable them make informed personal health choices and decisions. To achieve this purpose, Edgar and Hyde [3] recommend interpersonal communication between health care providers and patients as one of the most effective strategies for achieving positive health outcomes in patients, which incidentally, is the ultimate goal of the health care providers and patient communication Fong, Anat and Longnecker [5]. After all, patients are the raison’ deter for the establishment of hospitals, the training of medical personnel and all the extensive medical programmes of governments all over the world. Recent consensus in public health and health communication reflects increasing recognition of the important role of culture as a factor associated with health and health behaviours (institute of medicine, in Kreuter and Mc Clure [8]. Africa, in the portrayal of Andrews and Boyle, in Singleton Elizabeth and Krause [9], belongs to the magico-religious and determinist cultural belief groups, who believe that health problems are caused by factors such as supernatural forces, evil forces, enchantment, preordainment, etc and that cure can only come from the intervention of powerful medicine men making use of their charms and herbs. This cultural belief system is usually expressed in defaults in orthodox medical care such as resort to alternative medicine, non-adherence to medical advice and prescriptions, self medication, procrastinated resort to medical advice and their attendant consequences for health outcomes such as deterioration of patient health condition, worsening disease, treatment failures, increased hospitalization, deaths and increased health care costs Osterberg and Blaschke [12].

In Nigeria, right down to the grassroots, the problem of ill-health is further compounded by our collectivistic cultural orientation under which every sick person requires at least one, or more, healthy family member(s) to take care of him. The cumulative loss of man hours arising from this situation has far-reaching implications for our productive capacity as a people. while some studies show that the goal of achieving effective communication between health care providers and patients for better health outcomes are still beset by a number of problems one of which is patients cultural beliefs Diette & Rand [6]; Tongue et al. [7] others indicate that development, civilization and education have helped to introduce tremendous change in the beliefs and behaviour of Africans in this regard Ojua [10]; Kakung [11], thereby creating a knowledge gap. Therefore, this study is necessitated by a need to fully comprehend the place of cultural beliefs in achieving effective interpersonal communication between health care providers and patients as a precursor to securing patients’ confidence, dependence and adherence to orthodox medication.

Objectives of The Study

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

a) The objectives of the study are as follows:

b) To establish whether cultural health beliefs influence the interpersonal communication between health care providers and patients at the Ogume primary health care centre.

c) To determine the extent of influence of cultural beliefs on the patients’ adherence to medical recommendations and prescriptions at the centre.

d) To ascertain the influence of cultural health beliefs on the patients’ health seeking behaviour.

Research Questions

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

RQ. 1: Do the cultural health beliefs of patients at Ogume primary health care centre influence their communication with health care providers?.

RQ. 2: To what extent are the patients’ adherence to health care providers prescriptions at the centre influenced by their cultural health beliefs?.

RQ. 3: How do the cultural health beliefs of the patients at the health centre influence their health seeking behaviour?.

Operational Definition of Terms

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

Culture: The beliefs of the respondents regarding traditional medicine practice based on the diagnostic and therapeutic power of supernatural forces, herbs, stems, roots and other ingredients associated with the practice.

Health Beliefs: The beliefs of the respondents on the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of traditional medicine.

Healthcare Providers: The Ogume primary healthcare center staff comprising the doctor, midwives, nurses, health assistants and record keepers who render healthcare services to patients in Ogume community who patronize the Ogume primary health care center.

Culture Noise: The cultural health beliefs of the respondents that make it psychologically difficult for them to listen, understand, strictly adhere and implement to the letter the medical instructions, prescriptions, recommendations and advice communicated to them by the health care providers in the Ogume Primary Health Care Center.

Barrier: That which obstructs the reception, comprehension and adoption of health messages communicated between the healthcare providers and patients of Ogume primary healthcare center. Healthcare Provider/Patient communication. The healthcare-based interpersonal interaction and relationship between healthcare providers (ie doctors, midwives, nurses, healthcare assistants and record keepers) and the patients of Ogume primary healthcare center. Interpersonal communication: Healthcare-related one-onone verbal and non-verbal communication between the healthcare providers and patients at the Ogume Primary Healthcare Center. Health Seeking behaviour: Patients search for a perceived better diagnostic and therapeutic treatment of diseases and sicknesses.

Theoretical Framework

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

The theory used for this study is the theory of Reasoned Action. The theory was developed by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen in 1967 and was derived from previous research that began as the theory of attitude. The theory aims to explain the relationship between attitudes and behaviours within human action. It is used to predict how individuals will behave based on their preexisting attitudes and behavioural intentions. In other words, an individual`s decision to engage in a particular behaviour is based on the outcomes the individual expects will come as a result of performing the behaviour (Rogers-Gillmore et al., 2002). The ideas within the theory have to do with an individual`s basic motivation to perform an action. According to the theory, intention to perform a certain behaviour precedes the actual behaviour Ajzen & Madden [13]. Specifically, Reasoned Action predicts that behaviour intent is caused by two factors namely, attitudes and subjective norms. That is, behavioural intention is a function of both attitudes and subjective norms toward that intention. Also, it is observed that, depending on the individual and the situation, these factors might have different impacts on behavioural intention (Miller, 2005). It is further explained that the factor of attitudes and subjective norms have two components each that influence behaviour intent. The two components of attitudes are evaluation and strength of beliefs; while subjective norms are made up of the components of normative beliefs and motivation to comply Fishbein & Ajzen [14]. Invariably, Reasoned Action theory is concerned about how the introspective consideration of societal norms and personal values impact on the individual`s decision-making process and eventual behaviour. This theory is evidently relevant to this work because it is a study of how cultural health beliefs in our societies and the individuals understanding of same influence the decision of patients to behave in conformity with medical instructions, otherwise known as medical adherence behaviour.

Literature Review

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

Understanding Culture and Its Influence on Health Beliefs

According to Leininger [15], culture refers to the learned, shared and transmitted knowledge of values, beliefs and lifeways of a particular group that are generally transmitted intergenerationally and influence thinking, decisions and actions in patterned or in certain ways. In addition to this basic definition offered by Leininger, Purnel and Paulanka [16] add that culture is largely unconscious, both implicit and explicit, and dynamic, changing with global phenomena. Recent consensus in public health and health communication reflects increasing recognition of the important role of culture as a factor associated with health and health behaviours, as well as a potential means of enhancing the effectiveness of health communication programmes and interventions Institute of Medicine [17]. It is generally believed that by understanding the cultural characteristics of a given group, public health and health communication programmes and services can be customized to better meet the needs of its members. That is, the culturally bound beliefs, values and preferences a person holds influence how he interprets healthcare messages Singleton et al. [9]. In the view of Resniecow et al. in Kreuter and McClure [8], concordance between the cultural characteristics of a given group and the public health approaches used to reach its members may enhance receptivity, acceptance and salience of health information and programmes. In an attempt to capture this variability in the cultural outlook of different peoples, Andrews & Boyle, in Singleton, Elizbeth & Krause [9] present health belief models that different cultural groups use to explain health and illness into magicoreligious, biomedical and deterministic beliefs. They explain that magico-religious refers to belief in supernatural forces which inflict illness on humans, sometimes as punishment for sins, in the form of evil spirits or disease-bearing foreign objects as may be found among Latin America, African American and middle Eastern cultures; biomedical refers to the belief system generally held in the US in which life is controlled by series of physical and biochemical processes that can be studied and manipulated by humans, hence disease is seen as the result of the breakdown of physical parts from stress, trauma, pathogens or structural changes; and determinism, the belief that outcomes are eternally preordained and cannot be changed. Other sub-context cultures that have been advanced by scholars to explain the relationship between culture and health beliefs are familism and individualism Andrews & Boyle, in Singleton et al. [9]; high context and low context cultures Gigar & Davidhizar [18]; time orientation, present orientation and future orientation cultures Purnel & Paulanka [16] etc. Each of these cultural models are believed to influence health beliefs. Indeed, all cultures have systems to explain what causes illness, how it can be cured or treated and who should be involved in the process Mc Lauglin & Braun [19]. The extent to which patients perceive health information as having cultural relevance for them can have a profound effect on their reception to information provided and their willingness to use it. The fact that, cross-cultural variations also exist within particular culture groups makes the culture-health care relationship much more interesting.

Cultural Barriers that Affect Healthcare Provider/ Patient Communication

Beliefs and values affect the doctor-patient relationship and interactions Tongue et al. [7]. Divergent beliefs can affect healthcare through competing therapies, fear of the healthcare system, or distrust of prescribed therapies Diette and Rand [6]. The doctorpatient relationship is one of the most unique and privileged relations a person can have with another human being, just as having access to a well developed and effective association is important for the experience and objective quality of healthcare. Yet, over the past few decades, a number of cultural barriers have converged to reduce the ability of patients to have this archetypal relationship with physicians Hughes, in Fowler [20]. Fowler categorizes these cultural barriers into racial concordance of the doctor and patient, language barriers and medical beliefs. The author cautiously observes that another barrier to patient-physician communication, even if they speak the same language, is low health literacy of the patient which impairs ability to understand instructions on prescription drug bottles, appointment slips, medical education brochures, doctor’s directions and consent forms, and the ability to negotiate complex healthcare systems Of all these cultural barriers, the barrier of differences in medical beliefs are considered very fundamental to creating disharmony in the health care provider and patient communication relationship. As McLaughlin [19] points out, each ethnic group brings its own perspectives and values into the healthcare system, and many healthcare beliefs and practices differ from those of the traditional American healthcare culture. The expectation that the patients will conform to mainstream values frequently creates communication and care barriers that are further compounded by differences in language and education between patients and providers from different backgrounds. Fowler [20] maintains that when the two parties, comprising the doctor and the patient, have different views on medicine, the balance of cooperation and understanding can be difficult to achieve. This perception gap may negatively affect treatment decisions, and therefore may influence patient outcomes despite appropriate therapy Platt & Keating [21]. Patients construct their own versions of adherence according to their personal worldviews and social contexts which result in a divergent expectation of adherence practice Tongue et al. [7]; Sawyert & Aroni [22]; Middleton et al. [23]. Therefore, it is important to identify and address perceived barriers and benefits of treatment to increase patient adherence to medical plans by ensuring that the benefits and importance of treatment are understood Platt & Keating [21]. According to reports, Bolivia’s healthcare system is particularly invaded by this cultural barrier. As Bruun & Elverdam [24] put it, medical pluralism is a common feature in the Bolivian healthcare system, consisting of three overlapping sectors: the folk sector, the traditional sector and the professional sector. Whether in Bolivia, India, China or Africa, differences in medical health beliefs constitute a significant barrier to effective patient and provider communication which is absolutely necessary to giving and receiving adequate healthcare Fernadez [25].

Health Disparities: The Importance of Culture and Health Communication

Health disparities have been well documented even in systems that provide unencumbered access to healthcare, suggesting that factors other than access to care – such as culture and health communication – are responsible Thomas, Fine & Ibrahim [26]. Some of the causal factors that have been blamed for the problem of health disparities relate to individual behaviours, provider knowledge and attitudes, organization of the healthcare system, societal and cultural values. Accordingly, efforts to eliminate health disparities must be informed by the influence of culture on the attitudes, beliefs, and practices of not only minority populations but also public health policy makers and the health professionals responsible for the delivery of medical services and public health interventions designed to close the gap Thomas et al. [26] Cultural competence and patient centerednesss are two of such health intervention programmes designed to improve healthcare quality and thereby bridge the health disparity gap Saha et al. [27]. To achieve this purpose, healthcare providers must see the patients as unique; maintain unconditional positive regard for them; build effective rapport; use the psychosocial model to explore patients beliefs, values and meaning of illness, and to find common ground regarding treatment plans. Evidently, cultural congruence of patient, provider and message creates the right harmony for the enhancement of interpersonal communication and care. Therefore, Thomas et al. [26] propose the strategic matching of the cultural characteristics of all populations ethnic, racial or minority group with public health interventions designed to affect individuals within the group. It is their conviction that this may enhance receptivity to, acceptance of, and salience of health information and programmes. This approach is consistent with the documented evidence that factors such as belief systems, religious and cultural values, life experiences, and group identify act as powerful filters through which information is received, hence such factors should be considered in the development of health communication campaigns as well as in the healthcare provider and patient communication.

Cultural Explanation for Patients’ Non-Compliance with Medical Recommendations and Prescriptions

A patients culture not only shapes the meaning of the individuals behavior but also that persons health seeking and health related behaviours. Medication adherence is a major health behavior known to have a positive influence on patients quality of life. Boykins & Carter [28]. An increasing number of investigations have found positive relationships between clinicalpatient communication, treatment compliance, and a variety of health outcomes, including a better emotional wellbeing, lower stress and burn out symptoms, lower blood pressure, and a better quality of life (for both doctors and patients) Romani & Ashkar [29]; Street et al. [30]; in Amutio Kareaga et al. [31]. For example, in a study conducted by Fuertes et al. [32] using a sample of 101 adult outpatients from a rheumatology clinic, the results demonstrated that physician-patient working alliance predicted outcome expectations, patient satisfaction and adherence. Conversely, studies have also shown that non-adherence constitutes a major problem in achieving desired outcomes in the management of chronic diseases hypertension management Agyemang C et al. [33] and other consequential implications for healthcare such as deterioration of patient health conditions, worsening of disease, treatment failures, increased hospitalization, death and increased health care costs Osterberg & Blasche [12]. Incidentally, spirituality and religiosity are some of the socio-cultural variables that have been identified as determinants of such health behaviour as nonadherence to medication and medical instructions. Accordingly, there has been a growing tendency in the medical field to accord recognition to these socio-cultural health beliefs in conformity with the dictates of cultural competency and the perceived health benefits Penman, Oliver & Harrington [34]. McLaughlin & Braun [19] posit that cultural issues (such as spirituality and religiosity) play a major role in patient adherence. This position is corroborated by Miller, Thorsen & Mohr [35]; Ejikeme [36] in their submission that spiritual and religious activities have been noted to strengthen the faith of people and assist them with decision-making in health– related practices. Therefore, scholars and healthcare practitioners are better advised to channel more efforts towards maximizing the utility benefits of spirituality and religiosity in eliciting patient adherence behaviour.

Primary Healthcare Centres: Institution and Evolution in Nigeria

The international conference on primary health defines primary healthcare as “essential healthcare based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and their families in the community through their full participation and at cost that community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self determination” WHO, in Metiboba [37]. The needs in the health sector led to the establishment, among others, of primary healthcare centres (PCH) as the centre piece of health development in Nigeria Akande [38]. The scheme which was established by the Gowon administration in 1975 as part of the Third National Development Plan (1975- 1980) had the following objectives: increase the proportion of the population receiving healthcare from 25-60 percent; correct imbalances in the location and distribution of health institutions and provide the infrastructures for all preventive health programmes such as control of communicable disease, family health, environmental health nutrition and others and establish a health care system best adapted to the local conditions and to the level of health technology Sorungbe, in Metiboba [37]. Accordingly, the basic plan for the implementation of the scheme was to build in each local government area a comprehensive health institution that woud serve as the headquarters of the services, four primary health centres and 20 health clinics designed for a population of 150,000 Akande [38]. Government had since improved on this projection in terms of number of health centres available in each local government in Nigeria. However, despite government’s good intention in establishing this scheme, critical observers have continued to complain about its poor implementation. Aside from political, administrative and infrastructural factors militating against the successful implementation of the scheme so far, observers believe that the scheme still suffers from inadequate awareness and mass mobilization for increased involvement of the citizenry in PHC activities. For instance, Metiboba [39] insists that a great proportion of the rural population in many communities do not seen to know what PHC is all about, nor are they aware of the various services under the scheme.

Ogume Primary Health Care Centre

There are a total of 15 primary health care centres in Ndokwa West Local Government Area of Delta State and the Ogume Primary Health Care Centre is one of them. Prior to the coming of the Ogume primary health care centre in 2005, the building housing the centre was first used as the Community’s local dispensary in 1955, before it metamorphosed into a maternity clinic some years afterwards Emenimadu [40]; Ochonogor [41]. Ever since, the maternity has remained a prominent feature in the Ogume medical history. This is so much so that, more than 10 years after it has been upgraded to a primary health care centre, the indigenes still see it as a maternity clinic. This lack of awareness is, according to accounts, one of the reasons for the evident low patronage of the primary health care centre by the male population of the community till date. Recently, however, the state government constructed buildings meant for two new primary health care centres at Ogbe Ogume and Ogbagu Ogume quarters. These are yet to be occupied, except for the overgrown weeds that now occupy the premises. In the meantime, the male population continues to shun the health care centre that is in use for some other speculative reasons.

Method of Study

The research design of this study was based on the triangulation method. Wimmer and Dominick [42] define triangulation within the context of mass media research as the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods to fully understand the nature of a research problem. The complementary use of both qualitative and quantitative methods derives from a need to achieve a more dependable and reliable result. Under quantitative, the survey research method was adopted, while indepth interview was adopted under the qualitative approach. A total of 120 respondents were used for the survey method while another 14 respondents were used for the indepth interview. All the respondents were representative of patients in Ogume community receiving diagnostic and therapeutic attention at the Ogume primary healthcare center. Questionnaire and interview guide containing questions relevant to the cultural health beliefs of the respondents and its influence on their adherence to medical prescriptions were administered for the survey and indepth interview methods respectively.

Area of Study

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

The area of study is the ogume community in Ndokwa West Local government Area of Delta State. Ogume community is one of the 16 clans that make up Ndokwa West Local Government Area. Ogume is comprised of seven quarters namely, Ogbe-Ogume, Ogbole, Umuchime, Igbe, Utue and Obodougwa. Although, these seven quarters were originally given three primary healthcare centers, situated one each in Ogbe Ogume, Ogbole and Utue quarters only the one in Ogbe-Ogume is presently functional.

Population of Study

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

The population of study is represented here by the rural dwellers in the seven quarters that comprise Ogume community. The National Population Census Figure of 2006 credits Ogume with a total of 28,654 persons. Given the benefit of population growth and the time lapse between 2006 and 2017, there is need to statistically project a population figure for Ogume in 2017 using formula: PP = GP X PI X T; meaning

PP = projected population

GP = given population

PI = Population increase Index given as 2.28% by the United Nations for developing nations all over the world

T = The duration of time between the year of given population and year of study.

Therefore,

PP = 28,654 x 2.28% x 2017-2006

PP = 26, 654 x 2.28 X 11

PP = 28,654 X 0.0228X11

PP = 7,186.4

Actual population = 28654+7,186

35,840

Therefore the projected population of Ogume Community which will be used for this study is 35, 35,840.

Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

The study adopted the purposive sampling technique also known as judgmental sampling. The merit of purposive sampling stems from the fact that the researchers skill and fore-knowledge of sample characteristics, to a large extent, guide researchers choice of samples Nwodu [43]. The method imbues in the researcher the prerogative of judgment in selecting his respondents based on certain predetermined criteria. In this case, the predetermined criteria for choosing the respondents are as follows: one, they must be patients that have been in consultation with a healthcare provider in the health care center; two, such patient would have been in treatment at the health center between March and May, 2017; and three, they must be knowledgeable about the cultural health belief practices in Ogume Community. That constitute the focus of this study. After a series of visits to the health care center, especially on Tuesdays and Thursdays which are their busiest days, 120 respondents were purposively chosen for the survey approach, while another 14 respondents, two each from the seven quarters of Ogume Community were purposively chosen for the indepth interview.

Data Presentation and Analysis

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

Data obtained in this study are presented and analysed under two separate categories. While data obtained through the survey method are presented and analyzed using frequency table and simple percentages for ease of understanding; data obtained from the interview method are analyzed using the explanation building technique. Under the survey approach, a total of 136 copies of questionnaires were distributed. Out of this number, 120 copies were returned and found valid for use, representing 82.2% return rate, while the unused 16 copies represent 11.8%. On the other hand, 14 respondents were used for the in depth interview approach and their responses were analyzed using the explanation building technique.

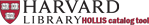

Table 1 above shows a sex distribution of female respondents, 109 (90.8%) as against 11 (9.2%) male respondents. It also shows that majority of the respondents, numbering 72 (60%), are between the age range of 20-30 years old. Others are 20 (16.7%) respondents between ages 31 – 41; 12 (10%) respondents between 42 – 52, 12 (10%) respondents between 53-63 years and only 4 (3.3%) respondents in the age range of 64 – 74 years old. Also, there is clear indication that majority of the respondents, 80(66.7%) are barely educated with most of them possessing First School Leaving Certificate (Primary Six) and ordinary level school certificate. Others are 16 (13.3%) respondents with A/L, OND and NCE; 12 (10%) respondents with Bachelors and above. Another 12 (10%) respondents did not have any formal education. On marriage, it is evident from the records that majority of the respondents, 92, representing 76.7% are married while 20 (16.7%) are single and 8 (6.6%) are divorced.

Data from Survey Method

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

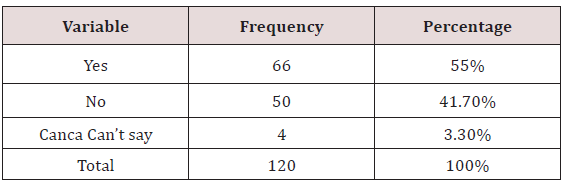

a. RQ. I: Do the cultural health beliefs of patients at the Ogume health care centre influence their communication with their health care providers? (Table 2).

Table 2: Respondents Views on How Cultural Health Beliefs Influence Communication with Their Health Care Providers.

As is evident from data on the above table, 66 of the respondents representing 55% expressed the opinion that their cultural health beliefs impeded effective communication between them and their health care providers; 50 of them, representing 41.7%, indicated that their cultural health beliefs did not in anyway influence their communication with their health care providers; while 4(3.3%) respondents were not sure whether their cultural health beliefs influenced their communication or not.

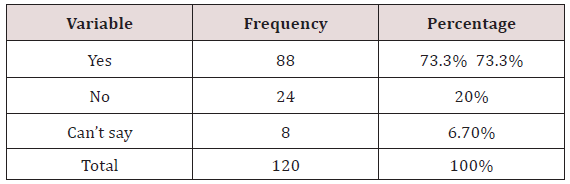

b. RQ. 2: Do the cultural health beliefs of patients at Ogume Health Care Centre influence their adherence to the health care providers prescriptions? (Table 3).

Table 3: Respondents Position on the Influence of Their Cultural Health Beliefs on their Adherence to the Health Care Providers Prescriptions.

From the above table, it is evident that the adherence behaviour of a high majority of the respondents was influenced by their cultural health beliefs. There are a total of 88 (73.3%) of such respondents. On the other hand are those respondents, 24(20%) who believe that their adherence to medical advice The management of the health centre blames this low patronage of men on cultural beliefs which make it a taboo for most men in the community to see a 1-7 day old baby. They explain that in order to avoid such occurrence, which is very likely in the health centres’ primary midwifery service, the men keep their distance from the health centre. Other opinions blame it on lack of awareness among the male population that the health centre offers healthcare services outside of the more common antenatal, midwifery and child immunization functions. was not affected by their cultural health beliefs. Another group of respondents, numbering 8(6.7%) failed to venture an opinion, either way.

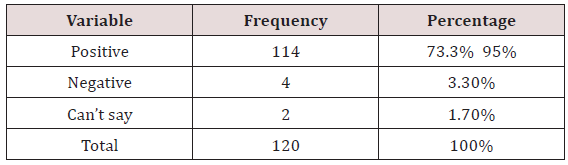

c. RQ. 3: Do the cultural health beliefs of patients at the Ogume health care centre influence their health seeking behaviour? (Table 4).

Table 4: Respondents Perception of How Their Cultural Health Beliefs Influence Their Health Seeking Behaviour.

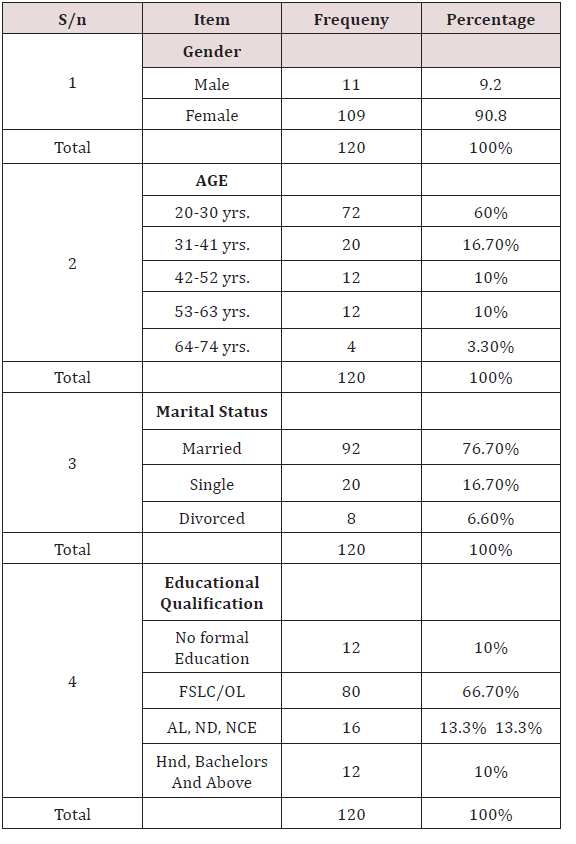

The above given responses show that virtually all the respondents, 114 amounting to 95%, believe that their cultural health beliefs influenced their health seeking behaviour. On the other hand, a few of them, 4(3.3%), are of the opinion that their health seeking behaviour is not influenced by their cultural health beliefs. In between these positions are 2(1.7%) respondent who chose to sit on the fence on the question as to whether or not their cultural health beliefs influence their health seeking behaviour or not. The above table shows that 78(65%) of the respondents consented to the fact that the family members influenced them on the choice of traditional medicine for treatment, while 40(33.3%) answered in the negative. Only 2(1.7%) respondents could neither say yes nor not (Table 5).

Data From Indepth Interview

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

The researcher subjected 14 of the purposively selected respondents, two each from the seven quarters that comprise the Ogume Community, to in-depth interview. Four basic questions along the lines of the study research questions guided the interview sessions. The responses are analysed as follows:

Influence of Cultural Health Beliefs on the Communication between the Health Care Providers and Patients

On this count, majority of the interviewees expressed the opinion that their cultural health beliefs greatly impeded their communication with their health care providers. They explained that their mind-set, arising from prior cultural health beliefs in traditional medicine, affected their trust and confidence in the competence of orthodox health care providers in the treatment of certain ailments. In the words of one of such respondents, Chief Lucky Ogwu, “there is a limit to what oyibo doctors can treat”. He listed some of these as bone fractures, diabolic poisoning and convulsion in children. According to him, in situations where orthodox medicine resorts to amputation for orthopaedic care, traditional medicine successfully sets the fractured area straight with the use of herbal applications. Another of the respondents who shares this opinion, Mrs. Cecilia Opone, was emphatic that no matter what the health care providers say, she will continue to take herbal medicine for her antenatal care. According to her, herbal medicine helps reduce the size of the placenta, which she calls “our mother” and thereby, potentially reducing the risk of complicated labour. However, on the reverse side, a few of the respondents said their cultural health beliefs do not influence their communication with health care providers. One of such respondents, Mrs. Abigail Oji, said that she had relied on traditional medicine during her first pregnancy and lost the baby in infancy. Ever since, she has resorted to orthodox medicine with better results. Hence, she now follows medical instructions to the letter.

Influence of Cultural Health Beliefs on Patients’ Adherence to Health Care Providers Prescriptions

Majority of the respondents admitted that their cultural health beliefs negatively influenced their willingness to adhere to health care providers prescriptions. In her reaction, Mrs. Paulina Nzeukwu complained that after several visits to the health center, she resorted to herbal medicine to solve the problem of the mysterious pain in her stomach which several X-rays could not detect. Hence, she discontinued her orthodox medication. In his account, Chief Lucky Ogwu insisted that you cannot mix them (English and Native medicine) because even English medicine are made from herbs too. According to him, “mixing them could cause overdose”. Hence, anytime he takes traditional medicine, he stops his orthodox medication regardless of health care providers instructions. On the flipside, a few of the interviewees maintained that they strictly adhere to health care providers instructions.

Influence of Cultural Beliefs on Patients Health Seeking Behaviour

All the respondents were emphatic that their health seeking behaviour towards a perceived better and more satisfactory treatment was positively influenced by their cultural beliefs in the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of medicine, orthodox or traditional. As one of the respondents who opted for anonymity, put it, “if I do not seek for better treatment where I believe I can get it, that means I am playing with my life”. This sentiment summarized the feeling of all the interviewees on this issue.

Discussion of Findings

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

a. Objective I: set out to establish whether cultural health beliefs influence health care providers and patients communication at the health care centre. The findings show that patients’ cultural health beliefs adversely influenced their communication with the health care providers. This communication problem stemmed from the contrariness in the health beliefs of both parties. This finding echoes earlier findings by researchers in this area. Fernandez [25] had found that differences in medical health beliefs constitute a significant barrier to effective patient and provider communication which is absolutely necessary to giving and receiving adequate healthcare. Fowler [20] in his own study found that when the two parties, comprising the patient and the provider, have different views on medicine, the balance of cooperation and understanding can be difficult to achieve. This is also consistent with the findings of McLaughlin and Braun [19] that the barriers of differences in medical beliefs are fundamental to creating disharmony in the health care provider and patient communication.

b. Objective 2: The finding that patients’ health beliefs negatively influenced their adherence to health care providers prescriptions conforms with the findings of earlier works on the subject. McLaughlin and Braun [19] had found that cultural issues such as religiosity and spirituality play a major role in patient adherence. Schouten [44] found that there is more misunderstanding, less compliance and less satisfaction in medical visits of patients with differing health beliefs from those of their health care providers. This finding resonates with those of Thorsen & Miller [35]; Ejikeme [36] who found that spiritual and religious activities have been noted to strengthen the faith of people and assist them with decision making in health related practices such as adherence. Other studies also found that patients construct their own personal worldviews and social contexts which results in divergent expectations of adherence practice Tongue et al. [7]; Sawyer & Aroni [22]; Middleton et al. [23].

c. On objective 3: which is how patients’ cultural health beliefs influence their health seeking behaviour, the findings show that majority of the respondents’ health seeking behaviours were influenced by their cultural health beliefs. The results evidenced that the patients’ health beliefs in the diagnostic and therapeutic power of medicine propelled them to seek for help from orthodox or traditional doctors, depending on the cultural perspectives of individual patients. While the majority sought help in traditional medicine, others who believed otherwise sought better and more satisfactory medical attention from orthodox healthcare providers. The findings here correspond with those of Ojua [10]; Katung [11]; Ejikeme [36] that the typical Nigerian rural dwellers resort to traditional medicine on the one hand; and to chemist shops, health centres and hospitals on the other hand for the treatment of sicknesses and diseases. In a related study on the Bolivian health care system, Bruun & Elverdam [24] had found a similar feature of medical pluralism in health seeking behaviour. Table 1 revealed a low level of patronage of the health centre by the male population of the community. The management of the health centre blames this low patronage of men on cultural beliefs which make it a taboo for most men in the community to see a 1-7 day old baby. They explain that in order to avoid such occurrence, which is very likely in the health centres’ primary midwifery service, the men keep their distance from the health centre. Other opinions blame it on lack of awareness among the male population that the health centre offers healthcare services outside of the more common antenatal, midwifery and child immunization functions. This finding is in tandem with the finding of Resniecow et al in Kreuter & Mc Clure [8] that, concordance between cultural characteristics of a given group and the public health approaches used to reach its members may enhance receptivity, acceptance and salience of health information and programmes. Also, the findings lend credence to an earlier finding by Metiboba [39] that a great proportion of the rural population in many communities do not seem to know what primary health care centre is all about, nor are they aware of the various services under the scheme. Furthermore, Table 5 shows clearly that an overwhelming number of the respondents were influenced by family members to take traditional medicine. This finding corroborates an earlier finding by Andrews & Boyle (2008) that cultural systems such as familism and individualism affect the health beliefs and health behaviours of patients in African Communities. Again, the findings of this study are consistent with the principles that govern the theory of reasoned action. Specifically, reasoned action predicts that behavioural intents are caused by individual attitude and the subjective norms towards that intention. It is further stated that, depending on the individual and the situation, these factors might have different impacts on behavioural intention Miller [45]. This theory is relevant to this work because it is a study of how the patients’ cultural health beliefs and understanding of same influence their decision to were influenced by cultural health beliefs and advice of family members. Finally, it is instructive to note that the findings of the two methods used for this study (survey method and indepth interview) are constituent with each other with the findings of one reinforcing and lending credence to the findings of the other.

Conclusion and Recommendations

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

The pre-eminence of good health over all other concerns of man is an incontrovertible fact of life. It is for this reason that responsible and responsive governments all over the world establish hospitals, train medical personnel and embark on all other extensive medical programmes designed to secure an effective health care system for its citizens. As part of this extended programme, health communication activities are carried out to inculcate health literacy in patients that will enable them make informed personal health choices. Edgar & Hyde [3] recommend interpersonal communication between health care providers and patients as one of the most effective strategies for achieving positive health outcomes in patients. Unfortunately, studies have shown that the goal of achieving effective communication between healthcare providers and their patients has always been beset by a number of barriers one of which is patients’ cultural beliefs Diette & Rand [6]; Tongue et al [7]; Ejikeme [36]. Incidentally, the findings of this study corroborate these earlier findings as it relates to cultural health beliefs constituting noise in the channel of communication between health care providers and patients, and thereby, impeding effective communication between the parties [46,47]. These cultural health beliefs, usually expressed in medical plurality and non-adherence to orthodox medical prescriptions; come with dire consequences among which are deterioration of patient health condition, worsening of disease, treatment failures, increased hospitalization, deaths and increased healthcare costs Osterberg and Blasche [12]. Given the consequences of cultural health beliefs to effective provider patient communication and its implications for patient health outcomes, the paper recommends as follows:-

a. One, that there should be enhanced facilitation of health communication and education for health care providers and receivers alike at the rural level on the significance of cultural health beliefs in achieving a sustainable health care system.

b. Two, that the Ministries of information and health at the local government areas should embark on concerted public awareness campaigns directed at the rural populace on the availability and benefits of the primary health care centres closest to them.

c. Three, that professional communicators who are indigenes of the rural communities should be drafted as part of the medical staff at primary health care centres with the aim of fostering a trust-yielding and confidence-boosting interpersonal relationship between the health care providers and patients at the centres.

d. Four, that town hall or village square meetings should be regularly organized, with qualified medical personnel as speakers, to address the rural dwellers on the risk implications of non-adherence, self-medication and such other abuses as well as disabuse their minds about certain traditional medicine related misconceptions they have.

e. Finally, that there should be more localized studies on the all-important place of cultural health beliefs and their implications, not only for effective provider patient communication but also for eventual positive patient outcomes.

References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Statement of Problem

- Objectives of The Study

- Research Questions

- Operational Definition of Terms

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Area of Study

- Population of Study

- Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Data Presentation and Analysis

- Data from Survey Method

- Data From Indepth Interview

- Discussion of Findings

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- References

- Abroms LC, Maibach EW (2008) The Effectiveness of Mass Communication to Change Public Behavior. Annual Review of Public Health 29: 219-234.

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS (2007) Does Tailoring Matter? Meta- Analytic Review of Tailored Print Health Behaviour Change Interventions. Psychol Bull 133(4): 673-693.

- Edgar T, Hyde JN (2004) An Alumni-Based Evaluation of Graduate Training in Health Careers, Salaries, Competencies and Emerging Trends. Journal of Health Communication 10(1): 5-25.

- Frank P, Jerant AF, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Tancredi DJ, et al. (2006) Studying physician interactional style and performance on quality of care indicators. Soc Sci Med 62(2): 422-432.

- Fong JH, Anat DS, Longnecker N (2010) Doctor-patient communication: A review. Ochisner Spring 10(1): 38-43.

- Diette GB, Rand C (2007) The Contributing Role of Health Care Communication to Health Disparities for Minority Patients with Asthma. Chest 132(5): 802S-809S.

- Tongue JR, EPPS HR, Forese LL (2005) Communication Skills for Patient- Centred Care: Research-Based, Easily Learned Orthopaedic Surgeons and Their Patients. Journal of Bone Joint Surg AM 87: 652-658.

- Kreuter MW, Mc Clure SM (2004) The Role of Culture in Health Communication. Annu Rev Public Health 25: 439-455.

- Singleton K, Elizabeth MS, Krause AB (2009) Disclosures. Online J Issues Nurs 14(3).

- Ojua TA (2000) Wealth creation in subsistence societies and the sociocultural effects. African Journal of Science and Policy Studies 2(2).

- Kakung PY (2001) Socio-economic factors responsible for poor utilization of PHC services in rural community Nigeria. Niger J Med 10(1): 28-29.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. The New England Journal of Medicine 353(5): 487-497.

- Ajzen I, Madden T (1986) Prediction of Goal-Directed Behaviour: Attitudes, Intentions and Perceived Behavioural Control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 22(5): 453-474.

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research: Reading, Addison-Wesley, MA, USA, pp.578.

- Leininger M (2002) Culture- Care theory: A major contribution to Advance Transcultural Nursing Knowledge and Practices. J Transcult Nurs 13(13): 189-192.

- Purnell LD, Paulanka BJ (2008) Transcultural Health Care: A Culturally Competent Approach (3rd edn), Philadelphia FA Davis.

- (2003) Institute of Medicine Keeping Patients Safe, Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses: Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Giger JN, Davidhizar R (2012) Culturally competent care: Emphasis on understanding the people of Afghanistan, Afghanistan Americans and Islamic culture and religion. Int Nurs Rev 49(2): 79-86.

- Mclaughlin L, Braun K (1998) How Culture Influences Health Beliefs.

- Fowler JD (2008) Cultural and Structural Barriers That Affect The Doctor-Patient Relationship: A Bolivian Perspective. A Thesis Submitted To Oregon State University In Partial Fulfillment For The Degrees Of B. Sc In Biology And B.A In International Studies In Biology (Honours Associate).

- Platt FW, Keating KN (2007) Differences in Physician and Patient Perceptions of Uncomplicated UTI Symptom Severity: Understanding The Communication Gap. Int J Clin Pract 61(2): 303-308.

- Sawyer SM, Aroni RA (2003) Sticky Issue of Adherence. Journal of Paediatric Child Health 39(1): 2- 5.

- Middleton S, Gattellari M, Harris JP, Ward JE (2006) Assessing Surgeons, Disclosure of Risk Information Before Carotid Endarterectomy. ANZ J Surg 76(7): 618-624.

- Bruun H, Elverdam B (2006) Los Naturalistas: Healers Who integrate traditional and Biomedical Explanations in their treatment in the Bolivian Health Care System. Anthropology and Medicine 38(3): 273- 283.

- Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Rosenthal A, Stewart A, et al. (2004) Physician Language Ability and Cultural Competence: An Exploratory Study of Communication with Spanish-Speaking Patients. J Gen Intern Med 19(2): 167-174.

- Thomas, Fine, Ibrahim (2004) Health Disparities: The Importance of Culture and Health Communication. AMJ Public Health 94(12): 2050.

- Saha S, Beach C, Cooper (2008) Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. Journal of the National Medical Association zoo(n) 100(11): 1275-1285.

- Boykins A, Carter C (2012) Interpersonal and Cross Cultural Communication for Advance Practice Registered Nurse Leaders. The Internet Journal of Advanced Nursing Practice 11(2): 1-8.

- Romani M, Ashkar K (2014) Burnout among physicians. Libyan J Med (9): 1-6.

- Street RL, Makoui S, Arora NK, Epstein RM (2009) How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns 74(3): 295-301.

- Amutio Kareaga A, García Campayo J, Delgado LC, Hermosilla D, Martínez Taboada C (2017) Improving Communication between Physicians and Their Patients Through Mindfulness And Compassion-Based Strategies: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 6(3).

- Fuertes JN, Anand P, Haggerty G, Kestenbaum M, Rosenblum GC (2015) The Physician-patient working alliance and Patient Psychological attachment, adherence, outcome expectations, and satisfaction in a sample of rheumatology patients. Behav Med 41(2): 60-68.

- Agyemang C, Bruijnzeels MA, Owusu Dabo E (2006) Factors associated with hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in Ghana, West Africa. J Hum Hypertens 20(1): 67-71.

- Penma J, Oliver M, Harrington A (2009) Spirituality and spiritual engagement as perceived by palliative care clients and caregivers. Journal of Advanced Nursing 26(4): 29-35.

- Miller WR, Thoresen CE (2003) Spirituality, religion, and health. An emerging research field. Am Psychol 58(1): 24-35.

- Ejikeme A (2016) Cultural Health beliefs influence on caregivers/ patients interpersonal Communication. An unpublished BSc. Project work. Derpartment of Mass communication. Chukwu Emeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam Campus, Nigeria.

- Metiboba S (2009) Primary Health Care Services For Effective Health Selected Rural Communities. Journal of Research in National Development 7(2).

- Akande T (2002) Enhancing Community Ownership and Participation in Primary Health Care in Nigeria. Nigeria Medical Practitioner 42(12): 3-7.

- Metibola S (2005) Social Factors, Community Participation and Health Development among The Okun Yoruba of Ijumu in Kogi State. An Unpolished PhD Thesis, Unilorin, Nigeria.

- Emenimadu G (2017) The Establishment of the Ogume Primary Health Care Centre Interview.

- Ochonogor CI (2017) The Establishment of the Ogume Primary health Care Centr. Interview.

- Wimmer RD, Dominick JR (2003) Mass Media Research: An Introduction. Belmont, Wadsworth, CA, USA.

- Nwodu LC (2006) Research in Communication and other Behavioural Sciences. Principles, methods and issues. Enugu: Rhyce Kerex Publishers.

- Schouten BC, Meeuwsen L (2006) Cultural Differences in Medical Communication: A Review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 64(1-3): 21-34.

- Miller K (2005) Communication Theories: Perspectives, Processes and Context. Mcgrawhill Education, New York City, USA, pp.368.

- (2002) Institute Of Medicine Speaking Of Health: Assessing Health Communication Strategies for Diverse Populations. National Academy Press, Washington DC, USA.

- Mary Rogers Gillmore, Matthew E Archibald, Diane M Morrison, Anthony Wilsdon, Elizabeth A Wells, et al. (2004) Teen Sexual Behaviour: Applicability of the Theory of Reasoned Action. Journal of Marriage and Family 64(4).

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...

.png)