Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4722)

Synbiotic Therapy in Infantile Colic - A Clinical Trial Volume 4 - Issue 3

Peymaneh Alizadeh Taheri1*, Armen Malekian Taghi2 and Mandana Motevaselian3

- *1Department of Neonatology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Bahrami Children Hospital, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Gastroenterology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Bahrami Children Hospital, Tehran, Iran

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Bahrami Children Hospital, Tehran, Iran

Received:May 19, 2023 Published: May 26, 2023

Corresponding author:Peymaneh Alizadeh Taheri, Department of Neonatology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Bahrami Children Hospital, Tehran, Iran

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2023.04.000188

Abstract

Background: Infantile colic is a common referral problem to pediatric clinics. The last criteria for the diagnosis of colic are the Rome IV criteria. There are different recommendations for the treatment of infantile colic but the response to each treatment is variable and no definite treatment has been recognized for this problem yet.

Aims: According to our last research, few clinical trials have surveyed the efficacy of synbiotics containing multi-strain probiotics in infantile colic, so the present study was performed.

Material and Methods: This study was performed on 60 infants (65% boys, mean age 62.26±15.6 days; mean birth weight: 3150±420 g) with the diagnosis of infantile colic. The infants of group A were randomly administered a synbiotic containing B. infantis, L. reuteri, L. rhamnosus, and fructooligosaccharides (FOS) (PediLact® [Zist-Takhmir Co., Tehran, Iran] drop), while group B received placebo (Dimeticon) [Toliddaru Co., Tehran, Iran]). The primary outcome was the response rate of each group, and the secondary outcome was the adverse effect of each drug.

Results:The response rate to the synbiotic containing multi-strain probiotics was significant after each week of intervention to the fourth week of intervention (Intragroup P-value <0.001). The response rate was also significant in synbiotic group after each week of intervention to the fourth week of intervention (Intergroup P-value <0.001) in comparison with Dimeticon. There was no adverse effect through each intervention.

Keywords:Synbiotics; infantile colic; crying; pedilact; fructooligosacharide

Methodology

Infantile colic- defined as recurrent and prolonged periods of fussing, irritability and crying without any obvious cause in otherwise healthy infants younger than 5 months which cannot be presented or resolved by caregivers- is estimated to affect about 20% of infants worldwide [1,2]. The condition has a self-limited course, starting in the second or third week of life with a peak around 6 weeks and resolving in the majority of cases by the age of 4 months [2]. However, excessive crying is considered the most important reason for pediatrician visits during the first weeks after birth, being a source of financial and psychological concern both for families and the healthcare system [3,4]. Moreover, prolonged, and severe symptoms related to infantile colic may be associated with behavioral and emotional outcomes in childhood [5]. Although the term “infantile colic” suggests a gastrointestinal (GI) origin, non-GI factors such as maternal physical and psychological problems, family tension and anxiety, hypersensitivity of the infant to environmental changes, and immaturity of the central nervous system have been suggested to play a role in infantile colic [2,6]. GI conditions such as gastro-esophageal reflux, lactose intolerance, GI motility disorders, and cow milk hypersensitivity have been long implicated as underlying factors, none being proven to have a causal relationship with colic in infants [7].

During recent years, the role of intestinal microbiota in etiopathogenesis of infantile colic has gained increasing attention. It has been reported that the baseline gut microbiota in infants can predict the persistence of crying at 4-week follow-up with a 65% accuracy [8]. Moreover, significant differences have been reported between the gut microbiota composition of colicky and noncolicky infants [9]. Infants with colic are known to have increased proteobacterial colonization, including gas-producing bacteria such as Escherichia and Klebsiella spp. while they have decreased bifidobacteria and lactobacilli colonization [10]. Although parental support and reassurance are regarded as the mainstay of management strategies in infantile colic, various interventions aiming at cessation of crying, pain relief, and improving the infant– family relationship have been proposed [11]. The evidence of the effectiveness of herbal remedies, oral sucrose or hypertonic glucose solutions, and drugs such as simethicone, dicyclomine and cimetropium is of low quality and prone to bias [12]. According to recent systematic reviews, there is high level evidence that probiotics (particularly Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938) can be effectively used in breast-fed infants [13,14]. Theoretically, synbiotics can be even more effective in the treatment of infantile colic as adding prebiotics to probiotic bacteria can augment the function and viability [15]. However, few studies have addressed the effectives of synbiotics in the treatment of infantile colic [13,14]. The present study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of PediLact® oral drop, a synbiotic containing three probiotic strains and fructooligosaccharide as prebiotic, in the management of infantile colic.

Methods

Diagnosis and Criteria

This parallel randomized triple -blinded clinical trial was performed between August 2019 to April 2020 in Bahrami Children Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Exclusively breast-fed infants aged 4 months or younger old presenting to the clinics of our center with a diagnosis of infantile colic based on the Rome IV criteria (crying or fussing for ≥ 3 hours per day for ≥ 3 days in a week in telephone or face-toface reports of the caregiver or total 24-hour crying and fussing of 3 hours or more measured by a 24-hour behavior diary) who did not respond (< 50% recovery rate) to conventional therapies (e.g. anti-bloating drugs, herbal products, etc.) were considered eligible to participate in this study. Preterm infants (gestational age at birth <37 weeks), those with acute or chronic diseases, congenital abnormalities, gastrointestinal or allergic problems, or infants who had taken antibiotics or probiotics 1 week before randomization were excluded.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents/ guardians of eligible infants who participated in this study. The details of the study protocols were approved by the ethical committee at Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS. MEDICINE.REC.1398.139). This study has been registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trails (IRCT20160827029535N6).

Study Protocol

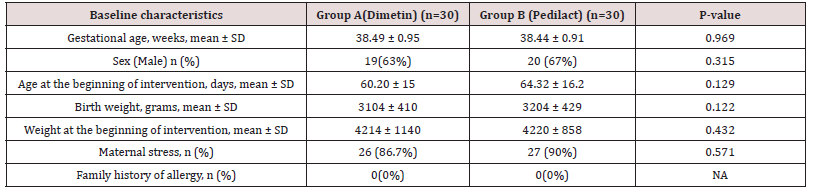

On enrolment, eligible infants underwent a thorough physical examination. Data on gestational age, gender, birthweight, weight at presentation, family history of atopy, and maternal stress were recorded in a checklist by a blinded investigator. A total of 60 enrolled infants were randomly allocated to groups A (30 participants) and B (30 participants). Infants in group A were given PediLact® oral drop [Zist-Takhmir Co., Tehran, Iran], a synbiotic formulation containing Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus rhamnosus, each 1 x 109 CFU per ml, plus fructooligosaccharides as prebiotic. Infants in the control group (group B) were given Dimetin® oral drop [Toliddaru, Tehran, Iran], containing 40mg/ml dimethicone. Both products were identical regarding the size, shape, and color of the bottles. The parents/ caregivers who administered the drugs, as well as the investigators and medical personnel who collected the data, and the statistician analyst were blinded to allocations. The primary outcome was the rate of improvement of infantile colic, defined as reduction of time and duration of crying and fussing per study protocol. The secondary outcome was the reported side effects. Parents/ caregivers of group A and B infants were asked to administer 5 oral drops of PediLact® 4 times a day or 7 oral drops of Dimetin® 4 times a day. The intervention period was 28 days. Mothers were given instructions not to take any probiotic-containing products during the study period. They were also asked to avoid additional medications for management of their infants’ colic.

Follow up and Scoring.

Infants were followed-up on days 7,14,21 and 28 after the beginning of intervention. On each visit, the times and duration of crying and fussing per day, number of days with crying and fussing in a week and any adverse events, e.g., constipation, vomiting, and skin reactions were recorded by the same investigator. Considering a type I error as 5%, a power of 80% and a potential dropout rate of 20%, a sample size of 33 infants per group was needed to detect a 50% reduction of the daily average crying time [13].

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS® software version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normally distributed quantitative and qualitative variables were respectively compared using the independent sample t-test and X2 test. Variables that didn’t have a normal distribution were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher Exact Test, as appropriate. All statistical tests were twotailed. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

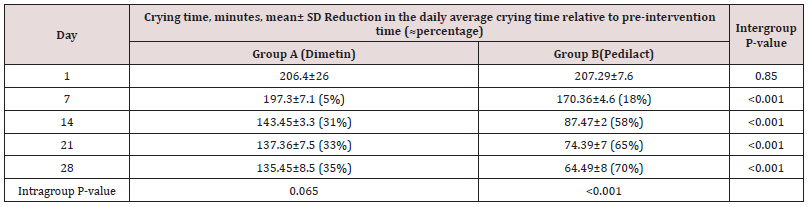

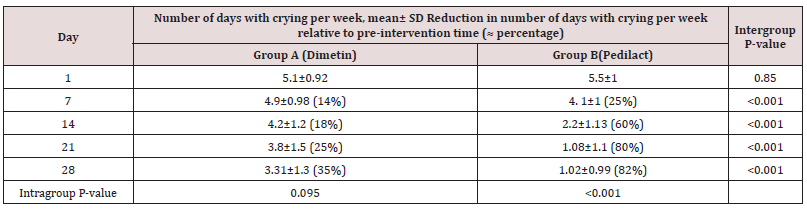

Of the 83 colicky infants assessed for eligibility, 13 infants were excluded from the study because of not meeting the inclusion criteria, unwillingness to participate in the study, etc. Seventy infants were randomly assigned to the two groups. Two patients in group A and four infants in group B discontinued intervention as soon as recovery of symptoms appeared or did not return to the clinic. Three infants in group A and one infant in group B were excluded from analysis due to incomplete data. Finally, 30 infants in each group (65% boys, mean age 62.26±15.6 days) completed the study (Figure 1). The two groups were comparable regarding baseline characteristics at the beginning of the study (Table 1). The mean crying time per day was comparable between the two groups on the first day. However, infants in Pedilact group had significantly shorter crying time on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 compared to those in Dimetin group (Intergroup P-value<0.001) (Table 2). Pedilact group also induced significantly less days with crying per week after each week of intervention to the fourth week of intervention compared to the Dimetin group (Intragroup P-value<0.001) (Table 3).

Discussion

The present triple-blind clinical trial study was performed to compare the effectiveness of a synbiotic containing B. infantis, L. reuteri, and L. rhamnosus with placebo in the treatment of infantile colic. There was a significant positive response rate in PediLact group in comparison with placebo after each week of intervention to the fourth week of intervention (inter-group comparison). On the other hand, this study also showed a significant difference in the response rate in PediLact group after each week of intervention to the fourth week of intervention “intra-group p-value” of <0.001 that indicates the significant positive response rate of PediLact drop on infantile colic. Colic is a complex disease with challenging therapeutic methods and drugs and no absolute treatment. Probiotic is a term driven from a Greek word meaning “for life”. Probiotics are useful living microorganisms that balance the bowel’s flora. A prebiotic is a food or dietary product that provides energy for useful bacteria and may induce their growth or activity. Synbiotics are a mixture of both prebiotics and probiotics that have a synergistic effect on the growth or activity of non-pathogenic bacteria [16-18]. Several researchers, including Bird et al., Dryl and Szajewska, and Pärtty et al., found the positive effect of probiotics on infantile colic [19-21]. Some other researchers, like Pandey et al, and Vandenplas and Savino reported that prebiotics were useful for the management of infantile colic, too [16,22]. Many investigations have shown the usefulness of specific strains of probiotics for the treatment of infantile colic. For example, studies conducted by Sung et al. and Savino et al. showed that L. reuteri DSM17938 was effective and safe for the management of infantile colic [23,24].

To the best of our knowledge, few clinical trials have studied the effectiveness of multi-strain synbiotics for the treatment of infantile colic [25-28], which was the reason why this study was conducted. Taheri et al, performed a study on 120 infants with the diagnosis of infantile colic resistant to conservative therapy. The infants randomly received either a synbiotic containing B. infantis, L. reuteri, L. rhamnosus, and fructooligosaccharides (FOS) (PediLact drop) or a synbiotic containing B. lactis and FOS (BBCare drop). The response rate to both synbiotics was significant after 1 week and after 1 month of intervention in both groups. The response rate was significantly higher in BBCare group after 1 week and after 1 month of intervention that shows the response to the synbiotic containing B. lactis was significantly more effective than the synbiotic containing B. infantis, L. reuteri, and L. rhamnosus in infantile colic. Neither synbiotic was associated with adverse effects [25]. Our present study compared PediLact drop with placebo in the treatment of infantile colic, while they compared the effect of two different synbiotics containing different probiotic strains in the treatment of infantile colic. Piątek et al designed a study on 87 infants aged 3-6 weeks with infantile colic (the Wessel criteria) who were randomly allocated to receive simethicone (n=33) or a multi-strain synbiotic (n=54) for 4 weeks. The multi-strain synbiotic contained Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lacticaseibacillus casei, Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Ligilactobacillus salivarius, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium longum and fructooligosaccharides). This study showed that the patients who received the multi-strain synbiotic had significantly higher response rates compared to simethicone in decreasing the average number of crying days and evening crying duration, through the last 3 weeks. They found no significant difference in the reduction of average number of crying courses per day during the last three weeks, between two groups. No adverse effects were reported for the two treatment groups [26]. The types of probiotic strains of their study were different from our present study. On the other hand, our study showed that our three-strain synbiotic had significantly higher response rates compared with Dimetin in decreasing both the average number and hours of crying courses per day. It also decreased average days of crying courses per week too.

Barekatian et al. conducted a study on 149 infants with the diagnosis of Infantile colic (the Wessel criteria) of whom 73 patients were treated with five drops of dimeticone, three times a day for three weeks and 76 patients received five daily drops of synbiotic for three weeks. Their synbiotic contained Bifidobacterium lactis (5 × 109 CFU per ml) and fructooligosacharide. Their study showed that both dimethicone and synbiotic improved the crying times, the duration, and the sleeping time per day significantly. There were no significant differences between the response rate of dimethicone and symbiotic groups. Barekatian et al. compared a synbiotic containing one strain of probiotic with placebo, while we compared a synbiotic containing three strains with placebo. The administered dose of the synbiotic was also different from our study [27]. Our study showed a significant positive response rate in synbiotic group in comparison with placebo after each week of intervention to the fourth week of intervention while there was no significant difference between the response rate of dimethicone and synbiotic groups in Barekatian’s study. Vijayalakshmi et al. studied 50 infants of whom 25 patients received standard treatment alone, and 25 patients received a synbiotic plus standard treatment. The synbiotic utilized in this study contained four types of probiotics including L. sporogenes, S. faecalis, C. butyricum and B. mesentericus. Their study showed that the synbiotic was an efficacious treatment and could be added to the standard treatment of infantile colic [28]. The dose and the types of probiotic strains of their study were different from our present study. Kianifar et al. studied fifty breast-fed infants ≤ 4 months of age with the diagnosis of infantile colic. They compared the effect of a synbiotic containing L. casei, L. rhamnosus, S. thermophilus, B. breve, L. acidophilus, B. infantis, L. bulgaricus plus FOS with placebo. The probiotic strains used in this study and the administered dose of the synbiotic were different from our study, while the type of oligosaccharide was the same as our study. On the other hand, Kianifar et al. compared a synbiotic containing seven strains with placebo, while we compared a synbiotic containing three strains with placebo. Kianifar et al. also reported a significantly higher rate of symptom recovery in the synbiotic group after 1 week, but it was not significantly higher after 1 month. In our study, the synbiotic had a significant positive response rate after each week of intervention to the fourth week of intervention [15].

Conclusion

This study showed that the synbiotic containing B. infantis, L. reuteri, and L. rhamnosus was significantly effective in the treatment of infantile colic. Neither treatment group was associated with adverse effects.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the personnel of the clinics of Bahrami Children Hospital. We also express our gratitude to the Research Development Center of Bahrami Children Hospital.

Additional Points

Limitations

Future studies with more participants are required to confirm these findings. The present study was limited to term infants with infantile colic. Further studies are recommended to survey the effect of synbiotics in premature infants with infantile colic. More searches are also recommended to study the effect of synbiotics containing different probiotic strains and synbiotics containing a single probiotic strain in infantile colic.

Author conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ Contributions

Peymaneh Alizadeh Taheri (PAT) and Armen Malekian Taghi (AMT)NS conceived and designed the study and experiment, Mandana Motevaselian (MM) gathered and processed the data, PAT and MM did literature search, PAT wrote the manuscript and revised the manuscript. The authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Zeevenhooven J, Koppen IJ, Benninga MA (2017) The New Rome IV Criteria for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Infants and Toddlers. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 20(1): 1-13.

- Banks JB, Rouster AS, Chee J (2021) Colic. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, USA.

- Halpern R, Coelho R (2016) Excessive crying in infants. J Pediatr 92(3 Suppl 1): S40-45.

- Steutel NF, Benninga MA, Langendam MW, Korterink JJ, Indrio F, et al. (2017) Developing a core outcome set for infant colic for primary, secondary and tertiary care settings: a prospective study. BMJ Open 7(5): e015418.

- Hemmi MH, Wolke D, Schneider S (2011) Associations between problems with crying, sleeping and/or feeding in infancy and long-term behavioural outcomes in childhood: a meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child 96(7): 622-629.

- Sarasu JM, Narang M, Shah D (2018) Infantile colic: An update. Indian Pediatr 55(11): 979-987.

- Sung V (2018) Infantile colic. Aust Prescr 41(4): 105-110.

- Loughman A, Quinn T, Nation ML, Reichelt A, Moore RJ, et al. (2021) Infant microbiota in colic: Predictive associations with problem crying and subsequent child behavior. J Dev Orig Health Dis 12(2): 260-270.

- Rhoads JM, Collins J, Fatheree NY, Hashmi SS, Taylor CM, et al. (2018) Infant Colic Represents Gut Inflammation and Dysbiosis. J Pediatr 203: 55-61. e3.

- de Weerth C, Fuentes S, de Vos WM (2013) Crying in infants: on the possible role of intestinal microbiota in the development of colic. Gut Microbes 4(5): 416-421.

- Daelemans S, Peeters L, Hauser B, Vandenplas Y (2018) Recent advances in understanding and managing infantile colic. F1000Res 7: F1000 Faculty Rev-1426.

- Biagioli E, Tarasco V, Lingua C, Moja L, Savino F (2016) Pain-relieving agents for infantile colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9(9): CD009999.

- Hjern A, Lindblom K, Reuter A, Silfverdal SA (2020) A systematic review of prevention and treatment of infantile colic. Acta Paediatr 109(9): 1733-1744.

- Ellwood J, Draper-Rodi J, Carnes D (2020) Comparison of common interventions for the treatment of infantile colic: a systematic review of reviews and guidelines. BMJ Open 10(2): e035405.

- Kianifar H, Ahanchian H, Grover Z, Jafari S, Noorbakhsh Z, et al. (2014) Synbiotic in the management of infantile colic: a randomized controlled trial. J Paediatr Child Health 50(10): 801-805.

- Pandey KR, Naik SR, Vakil BV (2015) Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics – a review. J Food Sci Technol 52(12): 7577-7587.

- DeVrese M, Schrezenmeir J (2008) Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics. in food biotechnology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 1–66.

- Cencic A, Chingwaru W (2010) The role of functional foods, nutraceuticals, and food supplements in intestinal health. Nutrients 2(6): 611-625.

- Bird AS, Gregory PJ, Jalloh MA, Cochrane ZR, Hein DJ (2017) Probiotics for the treatment of infantile colic: a systematic review. J Pharm Pract 30(3): 366-374.

- Dryl R, Szajewska H (2017) Probiotics for management of infantile colic: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch Med Sci 14(5): 1137-1143.

- Pärtty A, Rautava S, Kalliomäki M (2018) Probiotics on pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders. Nutrients 10(12): 1836.

- Vandenplas Y, Savino F (2019) Probiotics and prebiotics in pediatrics: what is new? Nutrients 11(2): 431.

- Sung V, D Amico F, Cabana MD, Chau K, Koren G, et al. (2018) Lactobacillus reuteri to treat infant colic: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 141(1): e20171811.

- Savino F, Garro M, Montanari P, Galliano I, Bergallo M (2018) Crying time and RORγ/FOXP3 expression in Lactobacillus reuteri DSM17938-treated infants with colic: a randomized trial. J Pediatr 192: 171-177.

- Taheri PA, Rostami S, Eftekhari K, Danesh S (2021) Synbiotic therapy in infantile colic resistant to conservative therapy: a clinical trial. JPNIM 10(1): e100128.

- Piątek J, Bernatek M, Krauss H, Wojciechowska M, Chęcińska-Maciejewska Z, et al. (2021) Effects of a nine-strain bacterial synbiotic compared to simethicone in colicky babies – an open-label randomised study. Benef Microbes 12(3): 249-257.

- Barekatian B, Kelishadi R, Sohrabi F, Yazdi M (2021) Efficiency of Dimethicone and Symbiotic Approaches in Infantile Colic Management. Iran J Neonatol 12(3).

- Vijayalakshmi T, Balachandran CS, Chidambaranathan S (2017) The effect of synbiotics on the duration of crying time in infants with abdominal colic. J Med Sci Clin Res 5(11): 30622-30626.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...