Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Scoping Review of Dental Anxiety among Children and Adolescents in Saudi Arabia Volume 4 - Issue 1

Abdullah Ali H Alzahrani*

- Department of Dental Health, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Albaha University, Saudi Arabia

Received: February 26, 2020; Published: March 05, 2020

*Corresponding author: Abdullah Ali H Alzahrani, Dental Health Department, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Albaha University, Saudi Arabia

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2020.04.000177

Abstract

Background: Dental anxiety (DA) has shown to be a complex concept associated with multiple factors including parents and children previous episodes of DA, poor oral health, avoidance of appointments, and unstable overall health. Thus, exploring this issue among Saudi children is highly important.

Aim: This scoping study aims to review the nature of research conducted on dental anxiety among Saudi children and adolescents.

Methods: Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review methodology was used. Relevant cross-sectional studies, case reports, cohort studies, randomized and non-randomized control trials, systematic and scoping reviews published between 1900 and the end of January 2020 were extracted from MEDLINE via PubMed, MEDLINE via Voids, Web of Knowledge, Cochrane, CINAHL, Embase, and Scopus, and were assessed for their eligibility.

Results: A total of 18 eligible studies were included. Six articles evaluated validity of different DA measures; four assessed effectiveness of different distraction techniques in reducing DA; four examined association of previous dental experiences with DA; and four explored causative factors associated with DA.

Conclusion: To advocate reducing the level of children’s DA, dentists must not consider only common causative factors such as anaesthesia, dental extraction, and numbness; but also socio-dental aspects related to DA including children’s previous painful experiences, gender, age, and oral health related quality of life.

Key Message

Dental practitioners must consider the common causative factors and socio-dental aspects associated with dental anxiety as this could help in reducing dental anxiety level among children.

Keywords: Dental anxiety; dental fear; dental phobia; children; scoping review

Abbreviations: DA: Dental Anxiety; OHRQoL: Oral Health Related Quality of Life; ACDAS: A beer Children Dental Anxiety Scale; CFSS-DS: Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale

Introduction

Dental anxiety (DA) is described as a sensation of apprehension about dental therapy that is not essentially associated with a specific external stimulus [1]. A recent review has demonstrated that evaluation of DA is important for not only identifying and managing patients with high levels of DA, but also managing pain in dental patients [2]. DA has been shown to be a complex decision making process in dental settings that is associated with multiple factors such as age, gender, parents and children previous episodes of DA, poor oral health, a history of excessive dental caries, avoidance of appointments, and poor oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL) [3-8]. DA is considered as a public health issue that commonly affects more children and adolescents than adults [9]. DA is reportedly caused by fear-evoking sensations, sights, and sounds, and fear of pain from dental drills and needles. It has uncovered that the reported levels of DA in childhood worldwide ranged from 10% to 29.3% [10]. This wide variation in DA prevalence may be related to the use of different measures of DA and different cut-off points to differentiate between those who are dentally anxious and those who are not. It is vital to reduce the disparities in the evaluation of DA among children and adolescents, as this will help in determining the most effective psychological techniques for alleviating DA as well as pain management strategies [11]. Nevertheless, dentists find it stressful and time-consuming to deal with children who experience DA [8,12]. Interestingly, dentists’ appearance has been shown to play a key role in reducing DA in children [13]. Further, dentists who have completed postgraduate courses in DA and undergone training for managing DA demonstrate better attitudes and higher use of behavioral management techniques with anxious children [14]. A scoping review aims to detect gaps in the literature, identify the main concepts reported, explore a wide territory of research, and highlight evidences that impact and can potentially improve practice in the field [15]. The present study seeks to identify gaps in the dental literature based on the nature and types of DA research conducted among Saudi children and adolescents, to explore the territory of DA in Saudi children and adolescents, and lastly, to report the results of research conducted on DA among Saudi children and adolescents. Scoping studies can also be used to identify the range of existing studies about a specific topic and to understand how those studies have been carried out [16]. This review determines the range of research conducted on DA among Saudi children and adolescents and how the research in this area has been conducted. The complexity and multifactorial of DA, as mentioned previously, [3-8] mean that it is highly important to investigate this issue among Saudi children and adolescents. This scoping study, therefore, aims to review and evaluate the nature of research conducted on DA among Saudi children and adolescents.

Materials and Methods

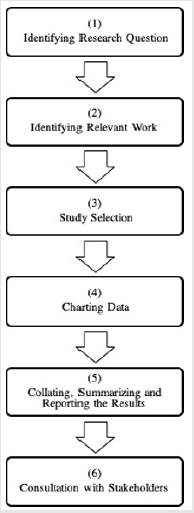

The scoping review strategy of Arksey and O’Malley was adopted in the current study [17]. This strategy consists of six key stages, as shown in Figure 1, and is described in detail below.

Stage: Identifying the research question

DA is considered as a key barrier in accessing dental care and individuals’ OHRQoL [5,18,19]. Impact of dental treatment on relationships and irritability were more common among patients with DA [20]. This highlights the significance of studying the nature of research on DA. This scoping review, consequently, emphasizes on exploring research on DA among Saudi children and adolescents.

Stage: Identifying relevant work

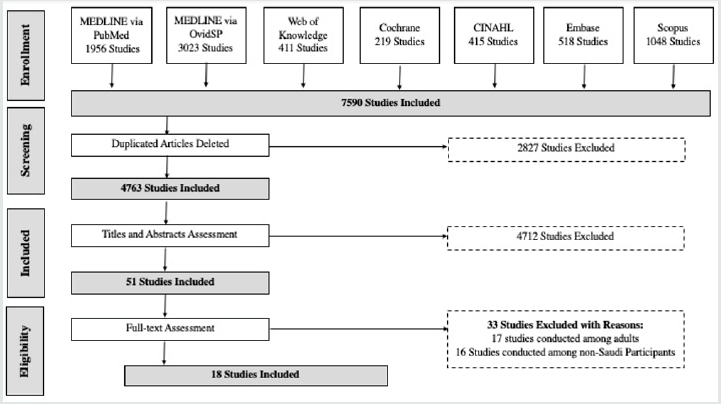

For this review, seven different resources were searched for relevant published material: MEDLINE via PubMED, MEDLINE via OvidSP, Web of Knowledge, Cochrane, CINAHL, Embase and Scopus. Figure 2 illustrates the process of searching and excluding articles. A combination of free-text search terms and controlled vocabulary were used: ‘dental anxiety*’.mp., ‘dental fear’.mp., ‘dental phobia’. mp., and (‘children’ or ‘adolescent’).mp. or ‘children*’.mp. or ‘adolescent*’.mp. All studies were considered, with the exception of studies that were conducted among adults and/or non-Saudi participants. This scoping review had no gender restrictions and included studies with all types of settings, including dental clinics, schools, and private or governmental clinics in Saudi Arabia. An Endnote library was established for organizing, classifying and systematizing relevant studies. A total of 7590 eligible studies were identified. All duplicated articles were deleted (n = 2827). As a result, 4763 articles were evaluated based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the next stage.

Stage: Selecting relevant studies

Based on the inclusion criteria for this scoping review, the

following publications were included:

a. Articles published between 1900 and the end of January

2020.

b. Studies conducted among Saudi children and/or

adolescents.

c. Studies on humans that were in the form of cross-sectional

research, case reports, case-control studies, retrospective

and prospective cohort studies, clinical randomized and nonrandomized

control trials, systematic reviews, literature

reviews, and scoping reviews. Based on the exclusion criteria,

the following were excluded.

a) Studies that were not written in English.

b) Research conducted on animals.

c) Studies conducted among non-Saudi children and/or

adolescents and

d) Studies carried out among adult participants.

The two reviewers independently searched all the sources. They initially screened the titles and abstracts of all the identified studies through the search to assess their applicability. The reviewers then conferred and discussed the eligibility of the included studies. There were no disagreements among them about the included articles. In total, 4712 studies were excluded based on the assessment of their titles and abstracts (see Figure 2). This left 51 articles for the fulltext assessment. At the full-text evaluation stage, both reviewers excluded 33 articles because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. This left 18 articles for the comprehensive review in the next step.

Stage: Charting data

In this stage, the two examiners individually read all 18 included articles and then conferred to examine their applicability to this study. The main author then assessed the eligibility of all the included studies based on the determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The other examiner independently evaluated and confirmed the eligibility of the studies.

Stage: Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

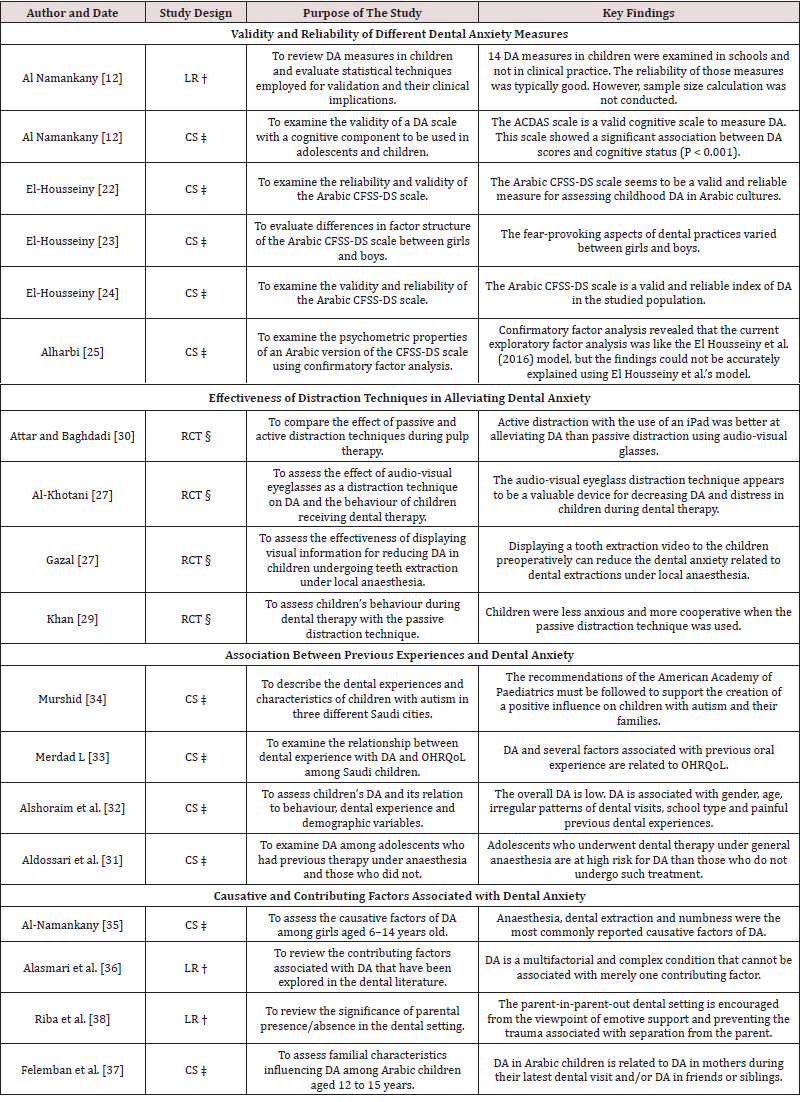

This study uses qualitative content analysis to condense and report the findings of the included studies. The findings were categorized under four headings to illustrate differences between the results based on the likeness of their aims and nature (see Table 1).

Table 1: Studies on Dental Anxiety among Saudi Children and Adolescents and their Key Purposes and Findings.

Stage: Consulting with stakeholders

This phase of the scoping study is not applicable to the current review.

Results

In total, 18 articles published between 2011 and 2019 were included in this study. The process of searching the literature and identifying relevant articles is depicted in the flowchart in Figure 2. Six of the articles were focused on evaluating the validity and reliability of different DA measures, such as A beer Children Dental Anxiety Scale (ACDAS) and Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS) [21-26]. Four of the selected studies assessed the effects of different distraction techniques on reducing the level of DA among Saudi children [27-30], and four other studies investigated the association of previous dental experiences and DA among Saudi children [31-34]. The last four studies explored the causative and contributing factors associated with DA, with one of the studies focusing specifically on the presence of a parent in the dental clinic [35-38]. Table 1 presents the included studies and their key aims and results. Most of the articles included were cross-sectional (11 studies) in nature, and the remaining studies were categorized as randomized controlled trails (four studies) and literature reviews (three articles). The key findings of these 18 included studies are described and discussed in detail in the following section.

Discussion

The findings of this review are categorized into four sections to illustrate and discuss the differences between the results of the included studies: Validity and reliability of different DA measures; Effectiveness of distraction techniques in alleviating DA; Association between previous painful dental experiences and DA; and Causative and contributing factors associated with DA. Following this, some limitations and conclusions based on the review findings are described.

Validity and reliability of different DA measures

Reliable and valid methods for evaluating DA in children could have important benefits for dentists and dental service suppliers [39]. For instance, these methods could be utilized for determining the prevalence of DA, identifying the symptoms and risk factors for DA in a population, and evaluating changes in DA over time [40]. The present study included one review article and one cross-sectional study on DA measures. Al-Namankany, De Souza [21], reviewed DA measures reported between 1960 and 2011 and validated 14 paediatric DA measures, but they were unable to validate 5 scales. Moreover, Al-Namankany, Ashley [26], reported that based on the ACDAS measure, there was a strong association between cognitive status and DA scores. An exploration of the dental literature has uncovered that the CFSS-DS scale is valid and reliable in several countries [41,42]. Further, this review found that the Arabic CFSSDS scale has been assessed four times for its validity and reliability [22-25]. It was concluded that this scale was reliable, consistent and valid [22,24]. However, there were differences in factor structure for this scale between Saudi girls and boys, with regard to factors associated with fear of dental procedures, fear of dentists, fear of strangers and fear of injections [23]. Furthermore, examining the psychometric properties of this scale revealed that the internal consistency of the Hospital Fear Subscale, Dental Fear Subscale and Stranger Fear Subscale corresponded to good and acceptable reliability [25]. However, it might be important to examine the CFSSDS measure across different regions of Saudi Arabia, considering the role of factors such as age, gender, previous DA experiences in parents, poor oral health, and poor oral health related quality of life [3-5]. Despite this, the Arabic version of the CFSS-DS scale is valid and reliable for measuring DA among Saudi children.

Effectiveness of distraction techniques in alleviating DA

Non-pharmacological passive and active distraction techniques could play a major role in alleviating DA among children [43]. The findings of the current review are consistent with this view and reveal that using a passive or active distraction technique could reduce DA among Saudi children and improve their response to their dentists. Passive distraction was not only effective in reducing children’s DA but also effective in helping children co-operate after local anesthesia [27,29]. Moreover, showing tooth extraction videos to children was found to alleviate DA associated with dental extractions under local anesthesia [28]. Yet, Saudi children preferred active distraction with an iPad more than passive distraction using audio-visual glasses [30]. Additionally, the use of music in dental settings is effective in reducing DA [44]. However, no study in the dental literature has directly examined the effectiveness of the music distraction technique on reducing DA among Saudi children.

Association between previous dental experiences and DA

Children’s previous experiences with dental treatment has been found to be associated with increase in their level of DA across several cultures [45,46]. Likewise, this review also found that previous experiences associated with DA was a contributing factor, in addition to gender, age, irregular patterns of dental calls and OHRQoL [32,33]. Though, dentists’ appropriate use of behavior management techniques is strongly associated with them having attained appropriate training and completed postgraduate courses in DA [14]. Yet, our review revealed that no studies so far have examined dentists’ skills and attitudes related to behavior management in Saudi children with DA. The evaluation of DA among special-needs children such as children with Down’s syndrome, autistic children and children with intellectual disabilities has received its fair share of attention in the literature across different countries [47,48]. Focusing on children those children is important because they are at a greater risk of dental diseases due to difficulties associated with expressing their dental needs and interacting with their parents or dentists [49]. Interestingly, there was only one study that evaluated DA among autistic Saudi children; this study concluded that the period of diagnosis was longer in these children and they needed more assistance to advance their oral health [34]. Consequently, evaluating DA in this vulnerable group of children in Saudi may be highlighted.

Causative and contributing factors associated with DA

Several pathways have been associated with DA in children, including informative, cognitive conditioning, verbal threat, and parental aspects [20,50]. Investigating these factors in children in detail may help in alleviating DA. However, only two studies have explored the causative and contributing factors associated with DA among Saudi children. These studies not only reported that the numbness caused by anesthesia and dental extraction were the most common causative factors of DA; but also concluded that DA is a multifactorial and complex occurrence that cannot be explained by merely one contributing factor [35,36]. Moreover, DA in the children was found to be significantly associated with DA in parents, siblings, friends and a parent-in-parent-out dental setting [37,38].Despite these findings, there are some shortcomings in the dental literature on Saudi children with regard to several informative, cognitive conditioning, verbal threat, and parental aspects associated with DA.

Limitations

There are two main limitation in this scoping review. First, there is a possibility that relevant articles were neglected because they were deposited in databases other than those that were searched here or because they were published in a language other than English. Exploring other databases and articles in other languages in the future might prove useful. An additional limitation of scoping studies is the lack of quality assessment of the included articles [16]. However, the emphasis of this study is on delivering a comprehensive review of the nature of the research that has been conducted on DA among Saudi children and adolescents. In this respect, the scope of the included studies with regard to DA was defined, the data charted, and the results collated, summarized, reported and discussed in detail.

Conclusions

In order to reduce the level of children’s DA, dentists must not consider only common causative factors such as anesthesia, dental extraction, and numbness; but also socio-dental aspects related to DA including children’s previous painful experiences, gender, age, and oral health related quality of life.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the generous help of my colleague, Dr Eltayeb Mohammed Alhassan (Head of Dental Health Department, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Albaha University, Saudi Arabia), in data extraction and confirmation of the eligibility of the included articles in this scoping review.

Source of Funding

This article did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest regarding the authorship and/or publication of this stud Title of the article: Scoping Review of Dental Anxiety among Children and Adolescents in Saudi Arabia.

References

- Folayan M, Idehen E, Ojo O (2004) The modulating effect of culture on the expression of dental anxiety in children: a literature review. Int J Paediatr Dent 14(4): 241-245.

- Lin C S, Wu S Y, Yi C A (2017) Association between Anxiety and Pain in Dental Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 96(2): 153-162.

- Carlsson V, Hakeberg M, Wide Boman U (2015) Associations between dental anxiety, sense of coherence, oral health-related quality of life and health behaviour-a national Swedish cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health 15: 100-106.

- Soares FC, Lima RA, de Barros MVG (2017) Development of dental anxiety in schoolchildren: A 2-year prospective study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 45(3): 281-288.

- Vermaire JH, van Houtem CMHH, Ross JN (2016) The burden of disease of dental anxiety: generic and disease-specific quality of life in patients with and without extreme levels of dental anxiety. Eur J Oral Sci 124(5): 454-458.

- Buldur B, Güvendi ON (2019) Conceptual modelling of the factors affecting oral health-related quality of life in children: A path analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent 18: 31-37.

- Liu Y, Gu Z, Wang Y (2019) Effect of audiovisual distraction on the management of dental anxiety in children: A systematic review. Int J Paediatr Dent 29(1): 14-21.

- Uziel N, Meyerson J, Winocur E (2019) Management of the Dentally Anxious Patient: The Dentist's Perspective. Oral Health Prev Dent 17(1): 35-41.

- Locker D, Thomson WM, Poulton R (2001) Onset of and patterns of change in dental anxiety in adolescence and early adulthood: a birth cohort study. Community Dent Health 18(2): 99-104.

- Shim Y S, Kim A H, Jeon E Y (2015) Dental fear & anxiety and dental pain in children and adolescents; a systemic review. J Dent Anesth Pain Med 15(2): 53-61.

- Williams KA, Lambaria S, Askounes S (2016) Assessing the Attitudes and Clinical Practices of Ohio Dentists Treating Patients with Dental Anxiety. Dent J (Basel) 4(4): 33-38.

- Buldur B (2018) Angel or Devil? Dentists and Dental Students Conceptions of Pediatric Dental Patients through Metaphor Analysis. J Clin Pediatr Dent 42(2): 119-124.

- Yahyaoglu O, Baygin O, Yahyaoglu G (2018) Effect of Dentists' Appearance Related with Dental Fear and Caries a status in 6–12 Years Old Children. J Clin Pediatr Dent y 42(4): 262-268.

- Strøm K, Rønneberg A, Skaare AB (2015) Dentists’ use of behavioural management techniques and their attitudes towards treating paediatric patients with dental anxiety. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 16(4): 349-355.

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H (2015) Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13(3): 141-146.

- Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD (2014) A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 5(4): 371-385.

- Arksey H, OMalley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of social research methodology 8(1):19-32.

- Beaton L, Freeman R, Humphris G (2014) Why are people afraid of the dentist? Observations and explanations. Med Princ Pract 23(4): 295-301.

- Levin L, Zini A, Levine J (2018) Dental anxiety and oral health related quality of life in aggressive periodontitis patients. Clin Oral Investig 22(3): 1411-1422.

- Kani E, Asimakopoulou K, Daly B (2015) Characteristics of patients attending for cognitive behavioral therapy at one UK specialist unit for dental phobia and outcomes of treatment. Br Dent J 219(10): 501-506.

- Al Namankany A, De Souza M, Ashley P (2012) Evidence based dentistry: Analysis of dental anxiety scales for children. Br Dent J 212(5): 219-222.

- El Housseiny A, Farsi N, Alamoudi N (2014) Assessment for the children's fear survey schedule dental subscale. J Clin Pediatr Dent 39(1): 40-46.

- El Housseiny AA, Alamoudi NM, Farsi NM (2014) Characteristics of dental fear among Arabic speaking children: a descriptive study. BMC Oral Health 14: 118.

- El Housseiny AA, Alsadat FA, Alamoudi NM (2016) Reliability and validity of the Children's Fear Survey Schedule Dental Subscale for Arabic-speaking children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 16(49): 1-9.

- Alharbi A, Humphris G, Freeman R (2019) The psychometric properties of the CFSS-DS for schoolchildren in Saudi Arabia: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Int J Paediatr Dent 29(4): 489-495.

- Al Namankany A, Ashley P, Petrie A (2012) The development of a dental anxiety scale with a cognitive component for children and adolescents. Pediatr Dent 34(7): e219-e224.

- Al Khotani A, Bello LA, Christidis N (2016) Effects of audiovisual distraction on children’s behaviour during dental treatment: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Acta Odontol Scand 74(6): 494-501.

- Gazal G, Tola AW, Fareed WM (2016) A randomized control trial comparing the visual and verbal communication methods for reducing fear and anxiety during tooth extraction. Saudi Dent J 28(2): 80-85.

- Khan S, Rao D, Jasuja P (2019) Passive Distraction: A Technique to Maintain Children's Behavior Undergoing Dental Treatment. Indo Americ J Pharmaceut Sci 6: 4043-4044.

- Attar RH, Baghdadi ZD (2015) Comparative efficacy of active and passive distraction during restorative treatment in children using an iPad versus audiovisual eyeglasses: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 16(1): 1-8.

- Aldossari GS, Aldosari AA, Alasmari AA (2019) The long-term effect of previous dental treatment under general anaesthesia on children's dental fear and anxiety. Int J Paediatr Dent 29: 177-184.

- Alshoraim MA, El Housseiny AA, Farsi NM (2018) Effects of child characteristics and dental history on dental fear: cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 18(1): 33-39.

- Merdad L, El Housseiny AA (2017) Do children's previous dental experience and fear affect their perceived oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL)? BMC Oral Health 17(1): 47-52.

- Murshid EZ (2011) Characteristics and dental experiences of autistic children in Saudi Arabia: Cross-sectional study. J J Autism Dev Disord 41(12): 1629-1634.

- Al-Namankany A (2018) Assessing dental anxiety in young girls in KSA. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 13(2): 123-128.

- Alasmari AA, Aldossari GS, Aldossary MS (2018) Dental Anxiety in Children: A Review of the Contributing Factors. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 12(4): SG1-SG3.

- Felemban OM, Alshoraim MA, El Housseiny AA (2019) Effects of Familial Characteristics on Dental Fear: A Cross sectional Study. J Contemp Dent Pract 20(5): 610-615.

- Riba H, Al Shahrani A, Al Ghutaimel H (2018) Parental Presence Absence in the Dental Operatory as a Behavior Management Technique: A Review and Modified View. J Contemp Dent Pract 19(2): 237-241.

- Porritt J, Buchanan H, Hall M (2013) Assessing children's dental anxiety: a systematic review of current measures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 41(2): 130-142.

- Armfield JM (2010) How do we measure dental fear and what are we measuring anyway? Oral Health Prev Dent 8(2): 107-115.

- Singh P, Pandey R, Nagar A (2010) Reliability and factor analysis of children's fear survey schedule dental subscale in Indian subjects. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 28(3): 151-155.

- Paglia L, Gallus S, Cianetti S (2017) Reliability and validity of the Italian versions of the Children's Fear Survey Schedule Dental Subscale and the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Eur J Paediatr Dent 18(4): 305-312.

- Armfield J, Heaton L (2013) Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: a review. Aust Dent J 58(4): 390-407.

- Klassen JA, Liang Y, Tjosvold L (2008) Music for Pain and Anxiety in Children Undergoing Medical Procedures: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ambul Pediatr 8(2): 117-128.

- Ten Berge M, Veerkamp JS, Hoogstraten J (2002) Childhood dental fear in the Netherlands: prevalence and normative data. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 30(2): 101-107.

- Nakai Y, Hirakawa T, Milgrom P (2005) The children's fear survey schedule–dental subscale in Japan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 33(3): 196-204.

- Isong IA, Rao SR, Holifield C (2014) Addressing dental fear in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study using electronic screen media. Clin Pediatr(Phila) 53(3): 230-237.

- Setiawati AD, Suharsini M, Budiardjo SB (2017) Assessment of dental anxiety using braille leaflet and audio dental health education methods in visually impaired children. Journal of International Dental and Medical Research 10: 441-444.

- Gordon SM, Dionne RA, Snyder J (1998) Dental fear and anxiety as a barrier to accessing oral health care among patients with special health care needs. Spec Care Dentist 18(2): 88-92.

- Carter AE, Carter G, Boschen M (2014) Pathways of fear and anxiety in dentistry: A review. World J Clin Cases 2(11): 642-653.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...