Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Presurgical Infant Orthopaedics - Journey So Far Volume 5 - Issue 2

Ashwina S Banaria1, Sanjeev Datanab2, Shiv Shankar Agarwal2* and SK Bhandarid3

- 1Resident, Department of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics, Armed forces medical college, India

- 2Associate Professor, Department of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics, Armed Forces Medical College, India

- 3Professor, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Armed Forces Medical College, India

Received: November 26, 2020; Published: December 07, 2020

*Corresponding author: Shiv Shankar Agarwal, Assistant Professor, Department of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, India

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2020.05.000206

Abstract

The successful management of patients with cleft lip and palate deformity requires a multidisciplinary approach. Historically, cleft lip and palate care starts with treatment modality of presurgical infant orthopaedics (PSIO). However, the necessity of presurgical orthopaedics in managing the resulting orofacial deformity is the discussion to ponder upon due to the variety of methodologies available and results produced by these devices. The objectives of this paper were to review the journey of PSIO appliances so far, basic principles of PSIO treatment, the various types of techniques and the protocol followed, and to critically appraise the advantages and disadvantages of these techniques. In conclusion, we believe that PSO treatment, with its objective to approximate the segments of the cleft maxilla may reduce the intersegment space in readiness for the surgical closure of cleft sites.

Keywords: Cleft lip and palate; presurgical infant orthopaedics; PSIO

Abbreviations: PSIO: Presurgical Infant Orthopaedics; CLP: Cleft Lip and Palate; NAM: Nasoalveolar Molding; DMA: Dentomaxillary Advancement Appliance; UCLP: Unilateral Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate

Introduction

Cleft lip and palate (CLP) are the most common congenital malformation caused due to variation in development of facial structure during gestation [1]. The incidence of patients with CLP is about 1.7 in 1000 live births globally [2]. The incidence is highest in Afghan population as 4.9 and lowest in Negroid population as 0.4 per 1000 live births [3,4]. The presence of cleft involving lip, palate and alveolus results in disfigurement and distorted growth and development. There is wide presentation of facial features among patients depending upon the severity of the cleft. A wide nostril base, separation in the upper lip of the cleft side is the characteristic feature of unilateral cleft defect. There is lateral and inferior displacement of affected lower lateral nasal cartilage which results distortions in the anatomic form of nose, tripod tilt in skeletal structure, a depressed dome, increased alar rim and deformities in apex of nostril. Shift in the base of the nose, deviation of septum to non-cleft side is also seen in patients with CLP. The separated premaxilla may overhang from the maxilla with variation in size [5,6]. Supervision and management of patients with CLP is a process that begins in infancy and continues in adulthood. Early treatment in the form of Presurgical Infant Orthopaedics (PSIO) is required to reduce the cleft width and to help maxillary arch development, thereby improving occlusion, feeding, speech, hearing, and language development and aesthetics [6,7]. PSIO has been defined as “use of forces to reposition tissues secondarily displaced due to a cleft deformity” [8]. Active and passive orthopaedic appliances have been developed for correction of CLP defect by using compressive & tensional forces or passively guiding growth. The aim of PSIO is to decrease the width of the cleft gap, to achieve a favorable alignment in the cleft segments within the initial few months of infancy prior to cheiloplasty, and to allow surgical repair with minimal tension [9]. In addition, there is improvement and ease in feeding, increased fluid intake, subsequently weight gain, improvement in functioning of tongue, reduced risk of aspiration and reduction in severity of dental & skeletal deviations.

Various methods and treatment protocol have been developed over ages and suggest PSIO prior to the primary surgery in patients with CLP for better surgical aesthetic results and prevent the social stigma. The aim of this review is to sum up the history, evolution, efficacy, advantages, disadvantages, complications, recent advances of different PSIO appliances, and critically analyze the evidence as well as the current status of PSIO.

Historical Perspective

PSIO has been a part of treatment strategy used in the management of patients with CLP for centuries. As early as in 1556, detailed explanation of the indications, surgical technique, and post-operative care of the cleft lip has been documented. A technique involving lip repair with cleft lip pins has been described by Amboise Pare in 1575. However, it was in the year 1689, Hoffmann demonstrated the use of facial binding to narrow the cleft and thereby prevent postsurgical dehiscence. The technique of retraction of the maxilla before surgical repair in patients with bilateral CLP was introduced in 1790 by Desault [10,11]. Adhesive tape binding usage in presurgical preparation was popularized by Hullihen [12]. Brophy in 1927 clinically demonstrated that silver wire passing cleft alveolus can be gradually tightened to approximate the alveolus before lip repair [13]. The modern school of presurgical orthopaedic to mould the alveolar segments using a series of plate system with active forces was introduced by 1950 McNeil [14] later popularized by Burston. Cupid’s bow and the philtrum symmetrical correction as Millard’s rotation advancement closure technique was introduced by Millard in1960 [15]. A pinretained active appliance which could simultaneously help in retraction of premaxilla and expansion of the posterior segments was introduced by Georgiade and Latham in 1975 [16]. The use of a passive orthopaedic plate for slow alignment of the cleft segments was described by Hotz in 1987 [17]. Matsuo’s (1988-91) series of research on molding of neonatal nasal cartilage and nostril with the help of silicone tubes was the gateway to invent newer modern methods [18-20]. The paradigm shift in the PSIO treatment was with the introduction of Nasoalveolar molding (NAM) by Grayson and Cutting in 1993, a novel technique in which presurgical molding of the alveolus, lip and nose is carried out in infants born with CLP [21].

Objectives of PSIO

Literature has highlighted the objectives of PSIO: to stimulate growth of patalal shelves, upper arch development, improvement in the projection of nasal tip leading to overall growth of the face. It also facilitates improvement in occlusion, feeding, speech, hearing, and language development. Eventually, PSIO aim at achieving a more uniform osseous base. The achievements of these objectives facilitate surgical closure and improve the final aesthetic result [22- 25].

Classification of PSIO appliances

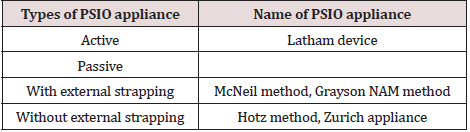

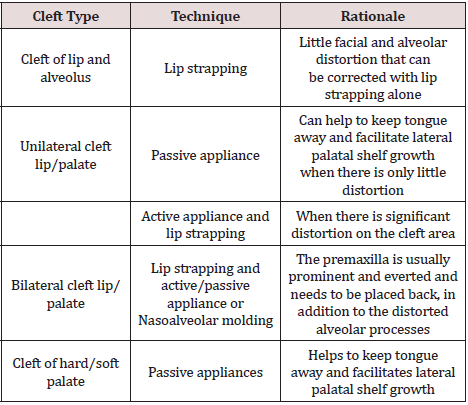

PSIO appliances can be classified into active and passive appliances based of force application (Table 1). Active appliances act by active forces being applied on the separated alveolar processes for growing them into desired anatomic position. The various appliances used for PSIO are discussed below and the technique of PSIO in different cleft types is summarized in Table 2.

Lip taping

Approximation of the alveolar segments within 5 mm of each other can be managed by using Lip taping. In this technique medical adhesive tape such as Steri-strips® is placed across the upper lip in the first week of life following which skin adherent dressing such as Tegaderm ®, are placed over the area of the cleft lip. Elastic forces will exert a retracting, backward pressure against the protruding premaxilla, improve their positions and allow definitive lip skin repairing. The clinical effectiveness of Lip taping is documented, however with only limited studies [26].

McNeil method

The pioneer work for alignment of the alveolar parts presurgical for patients with CLP was done by McNeil, who believed that a normal position of maxilla, alveolar & palatal cleft segment can be achieved by molding and approximating segments into correct preplanned position using a series of appliances. This method not only stimulated soft tissues to grow in cleft region but also modify the postnatal development of the maxilla. This method was further popularized by Burstone, an orthodontist. The advantage of this method is that a smaller number of appointment are required, hence encourage patients who may have to travel long distances for treatment [14,27].

Latham appliance

The Latham appliance also known as the Dentomaxillary Advancement Appliance (DMA) was developed to align the alveolar arch through rapid orthopedic correction and alignment of cleft segments was introduced by Dr Lantham and Georgiade [16,28]. Latham based his treatment concept on the facial growth hypothesis of Scott [29,30] with aim of the procedure ‘to carry the interrupted embryonic process to normal completion’ by maxillary alignment, stabilization of the alignment along with tunneling of the alveolar cleft with periosteum, and reconstruction of the nasal floor to support the alar base. This appliance is an active pin-retained appliance fixed surgically to the bone for patients with age around 2 to 5 months. The appliance works by simultaneously applying pressure to the cleft segments over a 4 to 6-week period to move the alveolar segments into proper position, which is followed by alveolo periosteoplasty and lip adhesion. According to Drs. Latham and Millard, these alignments allow the performance of gingiva periosteoplasty (GPP), providing stabilization of the maxillary segments and reconstruction of the nasal floor [31]. Greater values for cephalometric measurements in maxillary length, maxillary prominence and ANB angle has been found for patients treated with this appliance [32]. However, other authors have concluded that this appliance did not affect dental arch relationships in preadolescent children [33]. The problem associated with procedure is that, besides neonatal maxillary orthopedics, infant periosteoplasty is always performed, although it is more limited with less undermining of periosteum on the maxilla.

Hotz appliance

In Europe, the treatment principles of McNeil for neonatal maxillary orthopaedics were greatly modified by grinding away the acrylic in specific areas to bring out necessary alignment, known as Hotz appliance (Zurich approach). According to Hotz and Gnoinski, the primary aim of presurgical orthopedics is not to facilitate surgery or to stimulate growth, as postulated by McNeil, but to take advantage of intrinsic developmental potentials. In Zurich approach lip operation is performed at the age of 6 months while palate repair is postponed until 5 years of age [34,35]. The appliance is made of hard acrylic or a combination of hard and soft acrylic: it passively covers the alveolar segments and extends slightly into the area of the cleft and the buccal sulci. This appliance assists with both bottle-feeding and to allow some breast-feeding in infants with CLP. Harmonization in the vertical and transverse positions of the cleft segments has been found with Hotz plate therapy [36]. Long-term effects of the Hotz plate and early lip adhesion have been studied by several researchers and it has confirmed that arch width and length of the anterior part of the maxilla improves better than other treatment options [37]. Similarly, the two-stage palatoplasty in combination with application of the Hotz’ plate has good effects on the maxillary growth than one stage palatoplasty without Hotz plate [38].

Nasoalveolar molding

Earlier PSIO appliances were designed to correct the alveolar cleft only, despite the fact that the nasal deformity among these patients remains the greatest esthetic challenge. Grayson [21,39] described a new technique to presurgical mould the lip, alveolus and nose in infants born with CLP. The concept of naso alveolar molding (NAM) works on Matsuo’s principle; [18-20] that the nasal cartilage could be molded due to increased plasticity concurrent to increased levels of maternal estrogen if treatment is initiated within 6 weeks of life. The NAM appliance consists of an intraoral molding plate with nasal stents to mould the alveolar ridge and nasal cartilage concurrently. Beside other advantages of traditional plates, the main objectives of NAM appliances are improving nasal symmetry and lip aesthetics while elongating the columella and correcting nasal cartilage deformity. Hence, a less extensive surgery is required for the lip and nasal repair, and there is less tension on the reconstruction, greater nasal symmetry is be obtained after cleft lip repair using NAM therapy as well as better lip form, reduced oronasal fistulas and labial deformities, and a namely a 60% reduction in the need for secondary bone grafting [24].

Objectives of NAM in unilateral cleft lip and cleft palate (UCLP)

The main objective of NAM for UCLP is to reduce the severity of the original cleft deformity by reducing the width of the alveolar cleft segments and alignment of the base of the nose and lip segments [21]. Taping the lips together helps in correction of the inclined columella upright along the mid-sagittal plane. As the lower mid-face skeletal elements (alveolar ridge and lower maxilla) improve in relation to each other, the overlying soft tissue improves concurrently. The alar rim, which was initially stretched over a wide alveolar cleft deformity, shows some laxity that enables it to be elevated into a symmetrical and convex form. The nasal tip on the cleft side is overcorrected in its forward projection; this is achieved through the use of a nasal stent, an intra-oral acrylic plate, and surgical tapes [39-44].

Objectives of NAM in bilateral cleft lip and cleft palate cases

The main objective being the non-surgical elongation of the columella and also to center the pre-maxilla, along the mid-sagittal plane, retraction of the pre-maxilla in a slow and gentle process to achieve continuity with the posterior alveolar cleft segments. Reduction in the width of the nasal tip, improved nasal tip projection and increase in the nasal alar base width [21,39,43].

Benefits of NAM

Proper alignment of lip, nose and alveolus is achieved, thereby enabling surgeons for better surgical repair of the cleft deformity and hence reduce post-surgical breakdown [42,43]. Approximation of alveolar process before surgery also enables surgeons to perform gingivo-periosteoplasty successfully. NAM provides stable change in nasal shape with less scar tissue and better lip and nasal form. It also reduces the number of surgical revisions for excessive scar tissue, oro-nasal fistulas, nasal and labial deformities, due to proper columellar elongation and lengthening. With the alveolar segments in a better position and increased bony bridges across the clefts, the permanent teeth have a better chance of eruption in a good position with adequate periodontal support [39,40].

Complications of NAM

a) Locked-out segments: It may occurs due to the poor and

un-volunteered molding process, wherein the greater segment

moves more rapidly, without the change in position of the lesser

segment, as a result, the lesser segment gets locked out behind

the greater segment.

b) Nostril overexpansion (Mega-nostrils): This occurs when

the nasal stent application is started before the size of the cleft

gap is adequately reduced. The premature nasal stenting exerts

excessive force against the nasal tissue leading to excessive alar

expansion and resulting in mega-nostrils.

c) Tissue ulceration: It occurs due to application of pressure

by the intra-oral acrylic appliance, which may be due to ill-fitting

appliance. At times the area under the horizontal prolabium

band may also get ulcerated, if the band is too tight.

d) Skin ulceration: It may result due to frequent application

and removing of tape, resulting in irritated and ulcerated skin

over the cheek region.

e) Dislodgement of the acrylic plate: It is the complication

which may result in obstruction of the airway. This can only

occur, if the arms of the appliance are taped too horizontally or

with inadequate activation [39-44].

Prevention of the complications associated with NAM Therapy

a) NAM therapy must be closely monitored and volunteered

at timely basis with adequate application of mechanics and

robust principles of the therapy must be followed.

b) Tissue expanding direction and associated mechanics

should be monitored vigorously and nasal stenting should

commence only after the cleft gap is reduced by minimum 6

mm and softer denture liner must be covered over the nasal stent tip, so as to apply gentle forces.

c) Tissue ulcerations can be prevented by coating of tissue

lubricant over the appliance before insertion into the oral

cavity.

d) Skin ulcerations over the cheek region can be prevented by

using Duo-derm or Tega-derm, underneath the tape strapped.

e) Parents must be thoroughly educated to continue the use

of NAM appliance for their child until the therapy lasts. Feeding

instructions must also be given accordingly.

f) Motivating the parents to visit the dentist on scheduled

appointments and in timely manner is of utmost importance for

a successful NAM therapy [39-44].

Modifications

Recently NAM appliance has been modified by different authors in many ways. It includes modified muscle-activated maxillary orthopaedic appliance [45], incorporation of expansion screw [46], dynamic presurgical nasal remodeling intraoral appliance design [47], extra-oral nasal molding appliance [48], self-retentive appliance with orthodontic wire [49,50], use of TMA wire instead of SS wire for making nasal stent [51] and the latest technique of OrthoAligner “NAM” [52] & NAM custom aligners [53].

DynaCleft ® and Nasal Elevators

DynaCleft® is a premade nasal and alveolar molding device which can be used to successfully mold the upper lip, alveolus and nose prior to cleft lip repair. Traditional surgical adhesive tape (e.g. Silk tape, Steri-strips®) have been used in the past, unlike tape, DynaCleft® offers the benefit of being able to provide a constant approximation force with an elastic centre that allows it to conform to a baby’s mouth better because of its ability to expand and contract. Additionally, the controlled force provided to the prolabium and premaxilla could improve surgical results and decrease the necessity of early lip adhesion surgery. As the DynaCleft® device is pre-made; there is no need to create custom-made devices for the molding process. Studies have shown that with the use of DynaCleft® with a nasal elevator has produced results similar to that of NAM therapy. However, unlike the NAM appliance, it does not require adjustments with growth of the infant. Nasal elevators have been found to improve the shape of the nose and alae, thereby reduce the need for primary surgery to the nose in patients with UCLP. Due to its elastomeric core and stretch property, DynaCleft® allows the infant to feed and cry without limitation.

Conclusion

Many orthodontists working on patients with CLP have shown great enthusiasm for PSIO to improve surgical outcomes with minimal intervention. Although different forms of PSIO appliances are available, it seems that NAM therapy has been especially popular in all over the world. Undoubtedly, every orthodontist or surgeon aims to use the best treatment modality for their patients. Nevertheless, PSIO effects can be confounded by surgical type and timing of the primary repair, as is discussed in many studies. In such cases, one should be cautious when evaluating the particular outcomes for patients with CLP since it is difficult to differentiate the sole effect of an individual surgical or orthodontic intervention.

References

- Thronton JB, Nimer S, Howrd P (1996) The incidence, classification, etiology and embryology of oral clefts. Semin Orthod 2: 162-168.

- Mossey PA, Little J, Munger RG, Dixon MJ, Shaw WC (2009) Cleft lip and palate. Lancet 374: 1773–1785.

- Singh M, Jawadi MH, Arya LS, Fatima (1982) Congenital malformations at birth among live-born infants in Afghanistan, a prospective study. Indian J Pediatr 49(398): 331–335.

- Iregbulem LM (1982) The incidence of cleft lip and palate in Nigeria. Cleft Palate J 19(3): 201–205.

- Grayson BH, Maull D (2004) Nasoalveolar molding for infants born with clefts of the lip, alveolus, and palate. Clin Plast Surg 31: 149-158.

- Berkowitz S (2006) Cleft lip and palate Diagnosis and management. 2nd Ed Springer, Germany, UK p. 395-396.

- Kozelj V (2000) The Basis for Presurgical Orthopedic Treatment of Infants with Unilateral Complete Cleft Lip and Palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 37(1): 26-32.

- Jaeger M, Braga-Silva J, Gehlen D, Sato Y, Zuker R, Fisher D (2007) Correction of the Alveolar Gap and Nostril Deformity by Presurgical Passive Orthodontia in the Unilateral Cleft Lip. Ann Plast Surg 59(5): 489-494.

- Braumann B, Keillig L, Bourauel C, Jager A (2002) Three-dimensional analysis of morphological changes in the maxilla of patients with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 39: 1-11.

- Yang S, Stelnicki EJ, Lee MN (2003) Use of nasoalveolar molding appliance to direct growth in newborn patient with complete unilateral cleft lip and palate. Pediatr Dent 25: 253-256.

- Millard D (1977) Cleft craft: The evolution of its surgery. Bilateral and rare deformities. 2nd Boston, Little Brown, USA p. 81-88.

- Goldwyn RM, Hullihen SP (1973) Pioneer oral and plastic surgeon. Plast Reconstr Surg 52: 250-257.

- Brophy TW (1927) Cleft lip and cleft palate. J Am Dent Assoc 14: 1108.

- McNeil C (1950) Orthodontic procedures in the treatment of congenital cleft palate. Dent Records 70: 126-132.

- Millard DA Jr (1957) A primary camouflage of the unilateral harelook in Transactions of the International Society of Plastic Surgeons T Skoog, RH Ivy (Eds.), The Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, USA p. 160-161.

- Georgiade NG, Latham RA (1975) Maxillary arch alignment in the bilateral cleft lip and palate infant, using pinned coaxial screw appliance. Plast Reconstr Surg 56: 52-60.

- Hotz M, Perko M, Gnoinski W (1987) Early orthopaedic stabilization of the premaxilla in complete bilateral cleft lip and palate in combination with the Celesnik lip repair. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 21: 45-51.

- Matsuo K, Hirose T (1988) Nonsurgical correction of cleft lip nasal deformity in the early neonate. Ann Acad Med Singapore 17: 358-365.

- Matsuo K, Hirose T, Otagiri T, Norose N (1989) Repair of cleft lip with nonsurgical correction of nasal deformity in the early neonatal period. Plast Reconstr Surg 83: 25-31.

- Matsuo K, Hirose T (1991) Preoperative non-surgical over-correction of cleft lip nasal deformity. Br J Plast Surg 44: 5-11.

- Grayson BH, Cutting C, Wood R (1993) Preoperative columella lengthening in bilateral cleft-lip and palate. Plast Reconstr Surg 92: 1422-1423.

- Adali N, Mars M, Noar J, Sommerlad B (2012) Presurgical orthopedics has no effect on archform in unilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 49(1): 5-13.

- Kozelj V (2000) The Basis for Presurgical Orthopedic Treatment of Infants with Unilateral Complete Cleft Lip and Palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 37(1): 26-32.

- Marsh JL (1980) Comprehensive care for craniofacial anomalies. Yearbook medical publishers, Chicago, USA p. 13.

- Uzel A, Alparsian ZN (2011) Long-term effects of presurgical infant orthopedics in patients with cleft lip and palate: A systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 48(5): 587-595.

- Pool R, Farnworth TK (1994) Preoperative lip taping in the cleft lip. Ann Plast Surg 32: 243-249.

- Burston WR (1958) The early orthodontic treatment of cleft palate conditions. Dent Pract 58(10): 767-772.

- Latham RA, Kusy RP, Georgiade NG (1976) An extra orally activated expansion appliance for cleft palate infants. Cleft Palate J 13: 253-261.

- Scott JH (1956) The analysis of facial growth I: The anteroposterior and vertical dimensions. Am J Orthod 44(7): 507–512.

- Scott JH (1958) The analysis of facial growth II: The horizontal and vertical dimensions. Am J Orthod 44: 585–595.

- Millard DR Jr Latham RA (1990) Improved primary surgical and dental treatment of clefts. Plast Reconstr Surg 86: 856-871.

- Latham RA (2007) Bilateral cleft lip and palate: improved maxillary and dental development. Plast Reconstr Surg 119: 287-297.

- Chan KT, Hayes C, Shusterman S, Mulliken JB, Will LA (2003) The effects of active infant orthopedics on occlusal relationships in unilateral complete cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 40(5): 511-517.

- Hotz MM, Gnoinski WM, Nussbaumer H, Kistler E (1978) Early maxillary orthopedics in CLP cases: Guidelines for surgery. Cleft Palate J 15: 405-411.

- Hotz MM, Gnoinski WM (1979) Effects of early maxillary orthopaedics in coordination with delayed surgery for cleft lip and palate. J Maxillofac Surg 7: 201-210.

- Dürwald J, Dannhauer KH (2007) Vertical development of the cleft segments in infants with bilateral cleft lip and palate: effect of dentofacial orthopedic and surgical treatment on maxillary morphology from birth to the age of 11 months. J Orofac Orthop 68: 183-197.

- Hak MS, Sasaguri M, Sulaiman FK, Hardono ET, Suzuki A, et al. (2012) Longitudinal study of effect of Hotz's Plate and lip adhesion on maxillary growth in bilateral cleft lip and palate patients. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 49: 230-236.

- Silvera Q, Ishii K, Arai T, Morita S, Ono K, et al. (2003) Long-term results of the two-stage palatoplasty/Hotz' plate approach for complete bilateral cleft lip, alveolus and palate patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 31: 215-227.

- Grayson BH, Santiago PE, Brecht LE, Cutting CB (1999) Presurgical naso alveolar molding in infants with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 36: 486-498.

- Grayson BH, Cutting CB (2001) Presurgical naso alveolar orthopaedic molding in primary correction of the nose, lip, and alveolus of infants born with unilateral and bilateral clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 38: 193-198.

- Grayson BH, Shetye PR (2009) Presurgical naso alveolar moulding treatment in cleft lip and palate patients. Indian J Plast Surg 42(1): 56-61.

- Lee CT, Garfinkle JS, Warren SM, Brecht LE, Cutting CB, et al. (2008) Nasoalveolar molding improves appearance of children with bilateral cleft lip-cleft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg 122: 1131-1137.

- Shetye PR (2012) Presurgical infant orthopaedics. J Craniofac Surg 23(1): 210-211.

- Suri S, Tompson BD (2004) A modified muscle-activated maxillary orthopedic appliance for presurgical nasoalveolar molding in infants with unilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 41: 225-229.

- Retnakumari N, Vargheese M, Madhu S, Divya S (2013) A new approach in presurgical infant orthopedics using an active alveolar molding appliance in the management of bilateral cleft lip and palate patient: A case report. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 12: 11-15.

- Bennun RD, Figueroa AA (2006) Dynamic presurgical nasal remodeling in patients with unilateral and bilateral cleft lip and palate: Modification to the original technique. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 43: 639-648.

- Doruk C, Kiliç B (2005) Extraoral nasal molding in a newborn with unilateral cleft lip and palate: A case report. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 42: 699-702.

- Singh K, Kumar D, Singh K, Singh J (2013) Positive outcomes of naso alveolar moulding in bilateral cleft lip and palate patient. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 4: 123-124.

- Ijaz A (2009) Nasoalveolar molding of the unilateral cleft of the lip and palate infants with modified stent plate. Pak Oral Dent J 28: 63-70.

- Subramanian CS, Prasad KK, Chittaranjan , Liou E (2016) A modified presurgical orthopedic (nasoalveolar molding) device in the treatment of unilateral cleft lip and palate. Eur J Dent 10(3): 435–438.

- Batra P, Gribel B, Abhinav B, Arora A, Raghavan S (2020) OrthoAligner “NAM”: A case series of presurgical infant orthopedics (PSIO) using clear aligneres. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 57(5): 646-655.

- Bous RM, Kochenour N, Valiathan M (2020) A novel method for fabricating nasoalveolar molding appliances for infants with cleft lip and palate using 3-dimensional workflow and clear aligners. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Ortho 158: 452-458.

- Monasterio L, Ford A, Gutiérrez C, Tastets ME, García J (2013) Comparative study of nasoalveolar molding methods: nasal elevator plus dynacleft versus NAM-Grayson in patients with complete unilateral cleft lip-palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 50(5): 548-554.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...