Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Presentation of Untreated Dental Caries for Preventive Oral Health Care and Socio-Behavioural Attributes of Toddlers Attended a Public Dental Hospital in Sri Lanka Volume 6 - Issue 3

Gayan Surendra1, Irosha Perera2*, Manosha Perera3, Chandra Herath4 and Sumith Attanayake1

1Office of Deputy Director General (Dental Services), Ministry of Health, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2Preventive Oral Health Unit, National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka

3Alumnus, School of Dentistry and Oral Health, Griffith University, Gold coast, Queensland, Australia.

4Division of Pedodontics, Department of Community Dental Health, Faculty of Dental Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

Received:July 15, 2021 Published: July 26, 2021

*Corresponding author: Irosha Perera, Preventive Oral Health Unit, National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka, Ward Place, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2021.06.000237

Abstract

Background: Rapidly progressive dental caries without treatment (untreated dental caries) among toddlers denotes one of the leading unmet health needs. Preventive oral health care is essential to address this need.

Aim: To assess untreated dental caries burden, socio-demographic attributes and oral health behaviours of toddlers ≤ 3-years who attended a premier tertiary care public dental hospital in Sri Lanka.

Design: Retrospective data were collected for 24-months period comprising socio-demographic, oral heath behaviours, untreated dental caries among toddlers ≤ 3-years attended the Preventive Oral Health Unit of National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka. Toddlers were grouped as having <6 and ≥ 6 untreated carious teeth.

Results: Of 236 toddlers aged ≤ 3-years, the majority was aged 2-3 years and represented all ethnic groups. The overwhelming majority of mothers were housewives whilst 41.5% of fathers were skilled/unskilled workers. As reported by parents, three fourths of toddlers were without previous dental visits, but practiced assisted tooth brushing twice daily. However, 68.2% indulged in daily cariogenic dietary pattern which was significantly associated with the high burden of untreated dental caries among toddlers (p=0.007).

Conclusions: Parents across all social strata should be educated and empowered on modifying the daily cariogenic dietary pattern to a healthy balanced diet and accessing preventive oral health care for their toddlers at risk of progressive dental caries.

Keywords:Early childhood caries; untreated dental caries; toddlers; preventive oral health care; Sri Lanka

Introduction

Oral health is fundamental to overall health, growth, and wellbeing of children. Nevertheless, early childhood caries (ECC) the infectious, transmissible disease has become the leading chronic childhood disease across the globe affecting 30-50% children in high income countries [1,2] upto 90% in low- and middle-income countries [2] and vulnerable population groups [3]. As emerged from the findings of global burden of disease study 2010, untreated caries in primary (milk) teeth was the tenth most prevalent condition affecting 9% of global population [3]. Despite reaching epidemic proportions both in developed and developing countries affecting millions of child populations, this global public health priority [4] remains stagnant due to lack of priority action for its sustainable prevention and control. ECC is defined by the American Association of Paediatric Dentistry as presence of one or more noncavitated or cavitated decayed lesions, missing due to caries and filled tooth surface in any primary teeth in a child aged 71 months or younger [5]. Severe early childhood dental caries S-ECC denotes a sinister manifestation of ECC defined as occurrence of any sign of smooth surface caries in a child younger than 3-years [5]. The biofilm induced acid demineralization of enamel and dentine of primary teeth of toddlers and children often overlooked by parents, until the advanced stages. The consequent pain and infection negatively impact on quality of life of children and their parental care givers, with difficulties encountered by children in eating, sleeping, and performing vital daily activities [6,7]. Furthermore, recent research revealed that country level prevalence of ECC was associated with malnutrition among 0–2-year-olds and with anaemia among 3-5-year-olds [8]. Therefore, ECC poses a serious cause for concern in health and well-being of children and an essential element to integrate oral health into global health agenda of children.

ECC remains a persistent public health challenge in Sri Lanka: a developing lower-middle-income country substantiated by evidence from national oral health surveys 2015-2016 [9] as well as 2002-2003 [9]. According to 2015-2016 national oral health survey report, the prevalence of dental caries in the form of decayed, missing and filled teeth among 5-year-olds was 63%, of them 96.2% had untreated dental caries [10]. On the other hand, prevalence of untreated dental caries among Sri Lankan 5-year-olds was 60.7% [9]. Similar findings were emerged from national oral health survey report 2002-2003 demonstrating caries prevalence of 65.31% among 5-year-olds whilst reporting 63.51% prevalence of untreated dental caries [10]. Therefore, stagnation of reduction of ECC burden among 5-year-old children indicates a serious cause for concern. Moreover, a study conducted among semi-urban 1-2-year-olds revealed 32.19% prevalence of ECC, predominantly presented as untreated dental caries [11]. Further local research findings revealed ECC prevalence of non-cavitated decayed teeth ranging from 23% to 65% among the 12-24 months-old-toddlers and 17% to 32% among 12- 18-month-old-toddlers [12,13]. Exploring presentation and socio-behavioural attributes of ECC provides opportunities for sustainable interventions addressing the underlying causes by customized culturally appropriate strategies. Against this backdrop, present study was undertaken.

Objective: To assess the socio-demographic attributes, oral health behaviours and untreated dental caries among toddlers ≤ 3-years who attended a premier tertiary care public dental hospital in Sri Lanka.

Method

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted among toddlers and children attended the Preventive Oral Health Unit (POHU), National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Hospital Sri Lanka from 16 th July 2017 to 31st August 2018. The study population comprised children ≤ 5-years of age attended POHU for preventive oral health care. For the present paper, data on toddlers aged ≤3-years were included. Children having special needs such as birth defects, not presented with at least one parental care giver were excluded.

Study sample

Toddlers aged ≤3-years were included into the study using non-random consecutive sampling technique. The sample size calculation was done using following formula [14]. n=z2 p (1-p)/ d2 n=sample size, z=critical value of specified confidence interval (1.96), p=anticipated population proportion (90%), d=absolute precision required on either side of the proportion (5%). Anticipated proportion was obtained by conducting an exploration of prevalence of untreated dental caries among toddlers attended POHU in 2013-2014. n =1.962x 0.90 x 0.10/ 0.052 =138. Therefore, sample size was taken as 138.

Study setting

Preventive Oral Health Unit of National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka former Dental Institute, Ward place, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Data collection

An interviewer-administered, pre-tested, validated questionnaire was used for data collection. It comprised socio-demographic information, brushing habits and night feeding habits of the child, dietary pattern of the child, clinical oral examination data and treatment details. Questionnaire was developed in English language and translated into Sinhala and Tamil languages ensuring uniformity and language equivalence by expert consensus. Data were collected by Dental Surgeons attached to POHU performed as trained bi-lingual data collectors. The questionnaires were administered in preferable language to the parental care givers, and it was pre-tested at toddlers’ oral health screening programmes held at selected polyclinics held at Colombo Municipal Council region. This helped in improving the clarity, understandability cultural acceptability, time taken for completion and of the questionnaire. Data were collected ensuring privacy and confidentiality of the respondents and it took average 10 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Data analysis

Data were entered and analysed using SPSS-21 statistical software package. Frequency distributions and group comparisons were used for presenting data. Distribution of untreated dental caries among toddlers was assessed using tests of normality- Shapiro-Wilkinson and Kolomogorov-Smirnov tests. As the distribution was skewed, median score of untreated dental caries was used to dichotomize the untreated caries burden as <6 and ≥ 6. Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact tests of statistical significance were used for group comparisons to determine associated factors for untreated dental caries burden. Dietary pattern assessed by daily and weekly consumption of cariogenic food items comprising biscuit, buns, toffees/chocolates, milk packets etc. and healthy food comprising vegetables, fruits, pulses, yoghurt, cheese etc. Toddlers who consumed one or more cariogenic food items more than four days per week were categorized into “High consumption of cariogenic food”, those who consumed healthy food more than 4 days per week with infrequent consumption of cariogenic food items were categorized as “High consumption of healthy food” and toddlers who consumed both cariogenic and healthy food in a similar frequency were categorized into “Mixed” type.

Ethical aspect

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from Ethics Review Committee, Sri Lanka Medical Association. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. They were informed that participation was entirely voluntary which would not affect the optimal preventive oral health package provided for their toddlers. Administrative approval was obtained from Director, NDHTSL. Deidentified data were entered and analysed.

Results

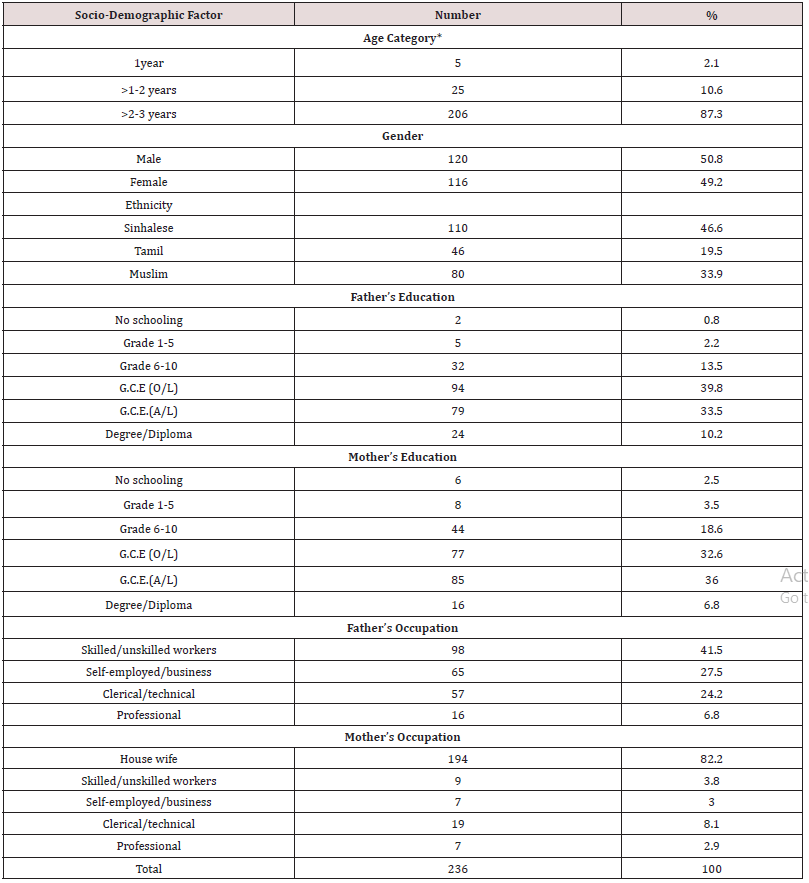

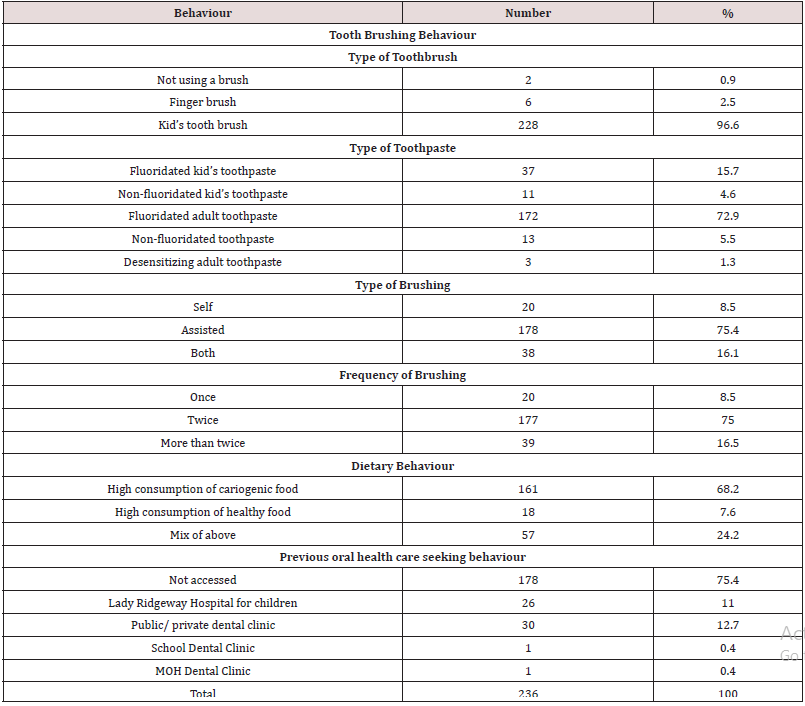

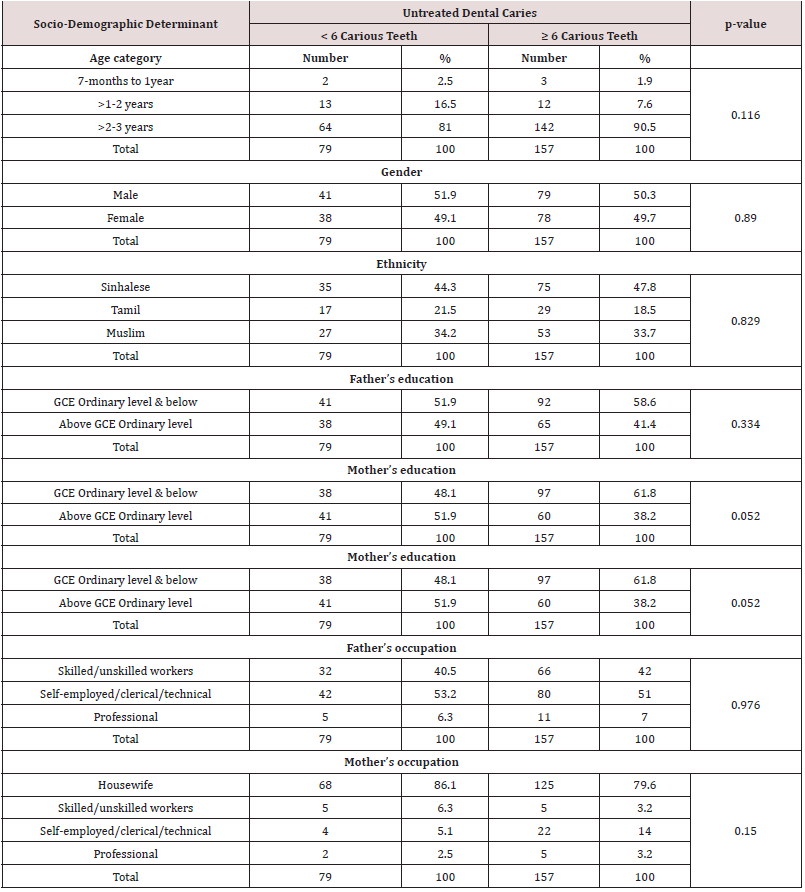

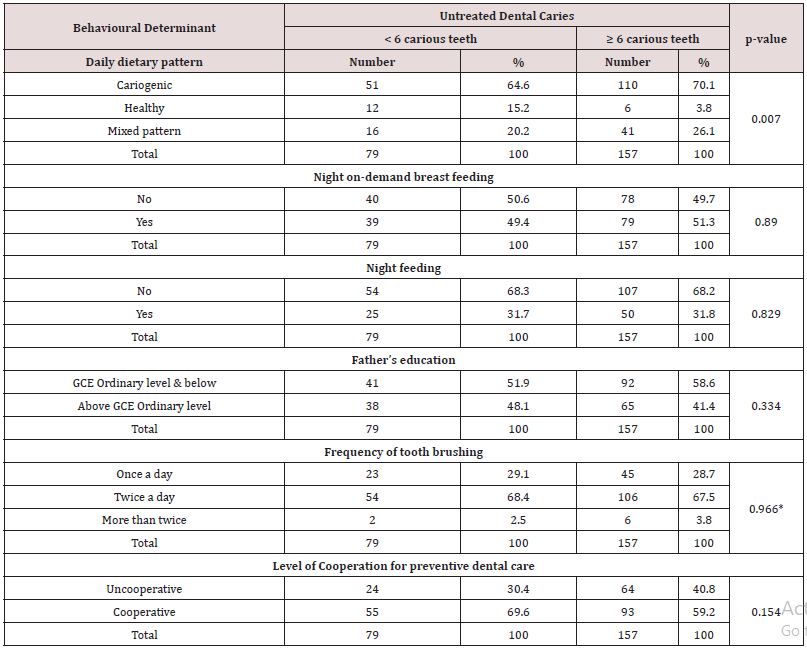

Table 1 demonstrates the socio-demographic profile of toddlers who attended the Preventive Oral Health Unit of National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka. The overwhelming majority (87.3%) was aged 2-3 years with the mean age of 2.55 years, with slight male preponderance (50.8%). Toddlers represented all three ethnic thus demonstrating ethnic diversity. The majority of fathers and mothers have attained GCE (O/L) and GCE (A/L) qualifications nevertheless, 0.8% of fathers and 2.5% of mothers had not attended schools. Moreover, 6.8% of toddlers had fathers and mothers who had obtained degrees and diplomas. According to occupational status the majority of fathers were skilled/unskilled workers (41.5%) or self-employed (27.5%) while the great majority of mothers were house-wives staying at home (82.2%). As shown in Table 2 below the overwhelming majority (96.6%) of toddlers were using kid’s toothbrush whilst 72.9 and 15.9% used adult and kid’s fluoridated toothpaste respectively as reported by parental care givers. Moreover, 75% practiced assisted tooth brushing twice daily. Over two third (68.2%) indulged on daily practice of cariogenic dietary pattern dominated by daily frequent consumption of biscuits, buns, toffees/chocolates with absence of consuming fruits, pulses and yams on a daily basis. Furthermore, 75.4% of toddlers with untreated dental caries had not previously accessed oral health care. As illustrated in Table 3, of socio-demographic attributes of toddlers, maternal educational attainment was marginally significantly associated with high untreated caries burden. Importantly, of behavioural determinants daily cariogenic dietary pattern was highly significantly associated with the high untreated caries burden of toddlers (p=0.007), whilst all other socio-demographic and behavioural attributes did not show significant associations.

*mean ± SD (2.55 years ±0.543 years).

Discussion

In the absence of established routine oral health screening for toddlers in Sri Lanka despite commendable service provision in maternal and childcare services, problem-based visits become the norm. Availability of and accessibility to child-friendly preventive oral health care services become fundamental to cater to toddlers having rapidly progressive ECC. Preventive oral health services should be targeted to address the socio-behavioural attributes of toddlers that increase their risk of ECC burden. Against this backdrop, present study explored and expounded the presentation and socio-behavioural attributes of untreated dental caries among a cohort of toddlers attended the preventive oral health unit (POHU) of National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka. Considering the fact of mean eruption time of first deciduous teeth among Sri Lankan children being 8.6 months [15], the burden on untreated dental caries presented among toddlers aged upto 2-years raises a serious cause for concern. Completion of the deciduous dentition (milk teeth) occurs at the age of 2 ½ years in general.

Nevertheless, toddlers as young as 12 months had presented with untreated early childhood dental caries. Untreated dental caries has garnered recognition as the leading unmet health need among children [16]. Early access to available preventive oral health care services is fundamental to prevent and control progression of ECC among toddlers and preschool children [17]. Sri Lankan national programme of oral health care for pregnant mothers has been introduced in 2009 [18], currently in place across the country yet indicating variable coverage and reported success in preventing the burden of ECC,19. In addition to Dental Surgeons, Paediatricians and Primary Health Care providers in maternal and child health services have a pivotal role to play in reducing the burden of severe ECC. It is well-known they are the first contact health care providers for toddlers much before accessing dental care services. This notion was clearly evident in present findings as ¾ of toddlers did not visited a dental clinic despite having progressive ECC [19].

As emerged from the findings, of an array of socio-behavioural attributes that were assessed, cariogenic dietary pattern underpinned by daily consumption of processed food items with refined sugar i.e.. biscuits, buns, toffees, chocolates, milk packets were significantly associated with high burden of untreated dental caries among toddlers. Moreover, mother’s educational attainment showed marginal significance in this association. These findings were in agreement with voluminous research that was conducted in other countries as well as in Sri Lanka linking the high ECC burden with Cariogenic dietary pattern among toddlers [20-25]. From public health through to molecular perspectives Cariogenic diet has garnered recognition as the predominant aetiological factor for untreated dental caries among toddlers and children [20-25]. Recent research evidence suggests significantly different oral biofilm associated microbiome associated with severe ECC among toddlers on cariogenic diets [26]. Furthermore, the caries preventive action of fluoride toothpaste could get attenuated by frequent consumption of refined sugars as sweets and biscuits [26]. Healthy dietary pattern underpinned by cutting down refined sugar which is the main aetiological for dental caries [26] and adherence to home cooked main meals and healthy snacks such as fruits, boiled vegetables and yams, pulses, eggs etc. has garnered recognition as a fundamental determinant in health and wellbeing of toddlers and children. The dietary recommendations speculated by the World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the importance of limiting the contribution of sugar <5% of total daily energy intake [27] which is more stringent than <10% limit, specifically aimed at reducing the risk of dental caries burden among children and adults [28,29]. Further, this scientific evidence is incorporated in the guidelines on complimentary feeding issued by Family Health Bureau, instructing not to add sugar for the food of the toddler up to 1-year and to add it sparingly in quantity and frequency afterwards. Despite overwhelming majority of mothers being educated housewives as emerged from present findings, they had seemingly overlooked providing healthy snacks for their toddlers. Therefore, it is important to provide dietary counselling for those mothers, during all health care seeking encounters for their toddlers that includes dental office as well. As it is difficult and challenging to achieve persistent behavioural changes [4], with regular follow up visits and customized packages of oral health education and counselling are required that are socio-culturally appropriate [4].

The findings revealed that majority of children were practicing assisted brushing twice daily with fluoride toothpaste. These findings corroborated the findings of other studies conducted in Sri Lanka [30] and elsewhere [31]. In the light of evidence of well proven caries protective effect of fluoride toothpaste having a high burden of untreated dental caries among toddlers with reported tooth brushing practices may appear contradictory at first glance. Nonetheless, , it is reasonable to speculate the reported brushing habits succeeded developing dental caries with symptoms rather than proceed before developing caries (Table 4). Accordingly, introducing a smear layer of fluoride toothpaste for tooth brushing from 1-3 years, with gradual increase in toothpaste content upto a size of a gram from 3-years-onwards has been strongly recommended for prevention and control of ECC among toddlers internationally and locally. Furthermore, it is not clear whether social-desirability response bias influenced the parental reports and the possible impact of common uncooperative behaviours of toddlers for tooth brushing. Parents should be imparted skills in gaining cooperation of toddlers for effective tooth brushing during antenatal visits and thereafter. Moreover, the fears and concerns of parents on introducing caries protective toothpastes with 1000 ppm for their high-risk toddlers should be explored and addressed. As emerged from the findings, night feeding practices dominated by on-demand night breastfeeding was common among present cohort of toddlers. Similar findings have been reported by others studies as well [32]. Present study did not find an association between night feeding practices and ECC burden, which was corroborated by another study [32]. However, in contrast to those findings a plethora of studies found prolonged breast feeding as a behavioural attribute that was significantly associated with the increased risk of ECC among toddlers and preschool children. A systematic review and meta-analysis on breast feeding and increased risk of ECC had synthesized evidence suggesting this connection but possibly confounded by other inadequately explored factors due to existed study limitations [33]. Therefore, authors recommended further studies with methodological refinements and qualitative explorations [33]. Current Sri Lankan guidelines insist on the need for exclusive breastfeeding upto six-months and continuation of the practice with appropriate complimentary feeding up to 2-years with the option of further continuation. However, mothers should be cautioned on night feeding practices and prolonged on-demand night breast feeding practices among toddlers aged ≥ 2-years having ECC. This becomes important as they need to address other modifiable risk factors such as less optimal tooth brushing and cariogenic dietary patterns that would further increase the risk and severity of ECC.

*Fisher’s exact test.

Recent Cochrane review revealed that providing advice on diet and feeding practices for pregnant women and other caregivers of children up to the age of 1-year had a limited impact on reducing the incidence ECC in early years of their children [34]. Hence, it is recommended to explore other interventions among care givers that have the potential to reduce the ECC incidence and features of interventions that make them more effective [34]. Another study reported that non-dental personnel could promote maternal oral health by provision of oral health education, risk assessment and referral whilst indicating optimism in potential sustained improvement in child oral health despite remaining weaknesses in existing evidence [35]. Preventive Oral Health Unit (POHU) of NDHTSL employs a dynamic preventive oral health care package comprising behavioural management of uncooperative children, parental/ care giver awareness and counseling, motivational interviewing, clinical preventive dentistry underpinned by professional fluoride applications and much more [16,17,25]. The aim is to make a toddler having high risk for dental caries converting to a low caries risk toddler by providing treatment for existing dental caries by preventive oral health care and improving oral health status. Literature supports the success of such strategies in oral health promotion of children however, demonstrating short-term influence in changing oral-health-behaviours of children [4]. Therefore, POHU keep the toddlers on maintenance therapy by regular follow up visits. Despite having a high burden of symptomatic untreated dental caries, three fourth of toddlers had not obtained oral health care as demonstrated in the present findings.

These findings corroborated that of Perera et al. [31]. This did not come as a surprise as preventive dental visits for toddlers are not in place as a routine practice in Sri Lanka compounded by high levels of dental anxiety among toddlers and children as well as dominated problem-based visit patterns in oral health care [25]. Nevertheless, the early childhood care and development package recommends dental visit to a dental clinic when the toddler is 1-year-old with or without having teeth and thereafter follow up visits in every 6-months as required. Paediatric health care encounters provide a unique opportunity in this regard to sensitize the parents. Moreover, the need for novel specific strategies to provide preventive dental care for toddlers at risk of ECC has been emphasized [23]. Nevertheless, our findings should be interpreted cautiously within its limitations. The small sample size and crosssectional study design provided a snap-shot of existing situation which does not indicate a temporal relationship. Moreover, consumption of cariogenic foods was not quantified to determine whether the dietary habit was directly related with high burden of ECC. This could become a limitation in making comparisons between low consumption and high consumption of cariogenic food. Ideally, a quantitative cut-off value on consumption is needed to define high or low intake of cariogenic foods or what is meant by ‘cariogenic’ , ‘healthy’ or ‘mixed diet’. Further, confounding variables such as plaque control, cariogenic bacterial counts and other risk factors for dental caries have not been accounted for which were obviously beyond the scope of this study. Further studies, therefore, warranted in this regard with methodological refinement.

Conclusions

As any untreated dental caries (tooth decay) among toddlers denotes many missed opportunities of a preventable and controllable leading chronic childhood disease, our findings demonstrate important practical implications. Parents across all ethnic and socio-economic strata should be educated and empowered by child health care providers and paediatric dental surgeons on the dire need for curtailing the refined sugar based unhealthy daily dietary patterns of their toddlers to reduce their untreated dental caries burden. Adherence to a healthy dietary pattern and accessing preventive oral health care services by toddlers would be a way forward in this regard.

References

- (2016) Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Oral health and dental care in Australia. Key facts and figures 2015. Canberra: AIHW, Dental Statistics and Research Series Cat no DEN 229.

- Peltzer K, Mongkolchati A (2015) Severe early childhood caries and social determinants in three‐year‐old children from Northern Thailand: a birth cohort study. BMC Oral Health 15: 108.

- Calvasina P, Muntaner C, Quinonez C (2015) The deterioration of Canadian immigrants' oral health: analysis of the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 43: 424‐432.

- Gibbs L, Waters E, Christian B (2015) Teeth Tales: a community-based child oral health promotion trial with migrant families in Australia. BMJ Open 5: e007321.

- (2008) Council on Clinical Affairs. Definition of Early Childhood Caries (ECC). American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

- Fernandes IB, Pereira TS, Souza DS, Ramos-Jorge J, Marques LS, et al. (2017) Severity of Dental Caries and Quality of Life for Toddlers and Their Families. Pediatr Dent 39(2): 118-123.

- Mansoori S, Mehta A, Ansari MI (2019) Factors associated with Oral Health Related Quality of Life of children with severe -Early Childhood Caries. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 9(3): 222-225.

- Folayan MO, El Tantawi M, Schroth RJ, Vukovic A, Kemoli A, et al. (2020) Early Childhood Caries Advocacy Group. Associations between early childhood caries, malnutrition and anemia: a global perspective. BMC nutrition 6: 16.

- (2018) National Oral Health Survey Sri Lanka 2015-2016. Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

- (2009) National Oral Health Survey Sri Lanka 2002-2003, Colombo: Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition, Sri Lanka.

- Kumarihamy SL, Subasinghe LD, Jayasekara P, Kularatna SM, Palipana PD (2011) The prevalence of Early Childhood Caries in 1-2 yrs olds in a semi-urban area of Sri Lanka. BMC Res Notes 4: 336.

- Shahim FN (2003) Factors of risk to early childhood caries in a selected district in Sri Lanka. Thesis (MD), Post Graduate Institute of Medicine. University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

- Nanayakkara NAR (2013) Prevalence & severity of Early childhood caries (ECC) and associated factors among aged 12-47 months attending weighing posts in medical officer of Health area Ampara (Master of science in Community Dentistry) University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

- Lwanga, Stephen Kaggwa, Lemeshow Stanley, World Health Organization (1991). Sample size determination in health studies : a practical manual / SK Lwanga, S Lemeshow. World Health Organization.

- Perera KAKD (2008) Effects of socio-demographic, maternal and childhood factors on deciduous dentition among the children in Kalutara District. Thesis (MD) Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

- Perera I, Herath C, Perera M, Dolamulla S, Jayasundara Bandara JM (2017) Service Delivery of a Preventive Oral Health Care Model to High Caries Risk Urban Children in Sri Lanka: A Retrospective, Descriptive Study. Journal of Advances in Medicine and Medical Research 20(3): 1-10.

- Perera IR, Wickramaratne PWN, Liyanage NLP, Karunachandra KNN, Bollagala AD, et al. (2013) Preventive dental clinic solutions to tackle early childhood dental caries. International Conference on Public Health Innovations. National Institute of Health Sciences Sri Lanka.

- (2009) Oral Health Care during Pregnancy. Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health Sri Lanka.

- Ranasinghe N, Usgodaarachchi US, Kanthi RDFC (2016) Evaluation of the oral health care programme during pregnancy in reducing dental caries in young children in the district of Gampaha, Sri Lanka. Asian Pac J Health Sci 3(4): 256-265.

- Un Lam C, Khin LW, Kalhan AC, Yee R, Lee YS, et al. (2017) Identification of Caries Risk Determinants in Toddlers: Results of the GUSTO Birth Cohort Study. Caries research 51(4): 271–282.

- Zhang M, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Li Y, Shao C, et al. (2020) Assessment of risk factors for early childhood caries at different ages in Shandong, China and reflections on oral health education: a cross-sectional study. BMC oral health 20(1): 139.

- Moimaz SA, Borges HC, Saliba O, Garbin CA, Saliba NA (2016) Early Childhood Caries: Epidemiology, Severity and Sociobehavioural Determinants. Oral Health Prev Dent 14(1): 77-83.

- Bissar A, Schiller P, Wolff A, Niekusch U, Schulte AG (2014) Factors contributing to severe early childhood caries in south-west Germany. Clin Oral Investig 18(5): 1411-1418.

- A Cehreli SB (2016) Evaluation of Possible Associated Factors for Early Childhood Caries and Severe Early Childhood Caries: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Survey. J Clin Pediatr Dent 40(2): 118-123.

- Karunachandra KNN, Bollagala AD, Perera IR, Liyanage NLP, Kottahachchi MJ, et al. (2013) Behavioural management strategies and oral health related behaviours of preschool children receiving preventive dental care. International Conference on Public Health Innovations. National Institute of Health Sciences Sri Lanka.

- Agnello M, Marques J, Cen L, Mittermuller B, Huang A, et al. (2017) Microbiome Associated with Severe Caries in Canadian First Nations Children. J Dent Res 96(12): 1378-1385.

- Moynihan P (2016) Sugars and Dental Caries: Evidence for Setting a Recommended Threshold for Intake. Adv Nutr 7(1): 149-156.

- Moynihan PJ, Kelly SA (2014) Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake: systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. J Dent Res 93(1): 8-18.

- Dissanayaka C, Gamage M (2020) A descriptive analysis of reasons for early childhood caries among a selected group of Sri Lankan preschool children. Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health 49(3): 246–250.

- Perera PJ, Abeyweera NT, Fernando MP, Warnakulasuriya TD, Ranathunga N (2012) Prevalence of dental caries among a cohort of preschool children living in Gampaha district, Sri Lanka: a descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 12: 49.

- Tham R, Bowatte G, Dharmage SC, Tan DJ, Lau MX, et al. (2015) Breastfeeding and the risk of dental caries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 104(467): 62-84.

- Riggs E, Kilpatrick N, Slack-Smith L, Chadwick B, Yelland J, et al. (2019) Interventions with pregnant women, new mothers and other primary caregivers for preventing early childhood caries. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (11): CD012155.

- Ajwani S, Johnson M (2019) Effectiveness of preventive dental programs offered to mothers by non-dental professionals to control early childhood dental caries: a review. BMC Oral Health 19(1): 172.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...