Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Prediction of Dental Bud Lag from Anthropometry Volume 7 - Issue 5

Yaniris Figueroa Céspedes* and Leslie Imara de Armas Gallegos

- Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Stomatology Raúl González Sánchez, Cuba

Received: June 08, 2022; Published: June 23, 2022

*Corresponding author: Yaniris Figueroa Céspedes, Master’s in Emergencies Dental Care, First Degree Specialist in Comprehensive General Stomatology, Third Year Resident of Orthodontics, Faculty of Stomatology Raúl González Sánchez. Havana, Cuba

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2022.07.000273

Abstract

Introduction: Anthropometric indicators at birth are usually the starting point for measuring child development, but can these measurements be taken as a predictor of tooth bud lag?

Objective: To determine which anthropometric variables are potentially predictive factors of dental bud lag.

Material and Methods: An observational, descriptive correlational, retrospective and cross-sectional study was carried out, between March 2020 and September 2021. The study population was made up of all children enrolled in the second and third year of life in three Nursery Schools belonging to the Vedado Teaching Polyclinic in the Plaza de la Revolución Municipality, which constituted the universe of this study. The sample consisted of those who attended from November to December 2020. All children were reviewed only once. The data was collected in a form created and validated for this purpose. Variables such as dental eruption, tooth bud gap, weight, height, head circumference at birth were studied. Their association was established using a logistic regression model, considering a significance level of 5%.

Most relevant results: From the statistical point of view, significant differences were found between low birth weight and delayed eruption of the primary dentition (p = 0.043). Similarly, an association was found between dental bud delay and Microcephaly (p=0.008). However, we discarded the alternative hypothesis of the existence of a negative relationship between size and bud lag, since we did not obtain a statistically significant association (p=0.301).

Conclusions: The anthropometric factors that are potentially predictive in the eruptive lag of our population are: birth weight and head circumference at birth as opposed to height at birth.

Keywords: Dental eruption; dental emergency; dental bud; tooth bud lag; birth weight; birth length; birth head circumference; anthropometry

Introduction

Anthropometric indicators at birth are usually the starting point for measuring child development, but can these measurements be taken as a predictor of tooth bud lag? In this sense, we can say that the correct evaluation of the dental bud gap should not be carried out in isolation, since the physical characteristics of the newborn should be considered, which are described by anthropometric measurements. The controversy lies in the significance of these factors, their relationships, their effect and the way they manifest themselves. The elucidation of these relationships represents an important aspect to investigate, especially in children from day care centers, who are in a stage in which decisive changes occur at the level of craniofacial growth and occlusion development, and therefore, we can better observe the association of these two characteristics. Knowledge of these variables has great practical application, since their alteration could suggest or alert the stomatologist of a delay in the child’s development, which is of great importance in terms of detecting risks and anomalies that affect dental development during the first childhood., allowing timely and convenient decision making. Reason why anthropometry should be an element to take into account in our daily practice, if it is a dental outbreak, as part of an evaluation of the complete health status. Thus, we have a valuable asset in the etiological diagnosis, as a tool in treatment planning. Therefore, we intend that it constitutes an invitation to reflect on the current situation regarding topic [1,2].

But if we go back in history, we find that in 1957, Falkner published one of the first studies that related the eruption of primary teeth with anthropometric variables [3]. Recent publications [2-4] are oriented in this sense in various regions of the country. However, today they are not of considerable magnitude, being restricted to very specific samples and locations. The achievement of this purpose requires the successive development of research in the areas of health. Reason why the results cannot be extrapolated to the Havana or Cuban population. However, it constitutes scientific evidence and a useful reference, given the scarcity of publications on the subject that has already been commented on [5-9]. Everything expressed conditions the fact that we are facing an investigation that is very necessary and, above all, timely. Therefore, the key question of this research is: What anthropometric factors are potentially predictive of dental bud lag? So, the intention of this work is none other than: To determine which anthropometric variables that constitute potentially predictive factors of the dental bud gap. To achieve this major objective, we have as specific: Determine the association of weight, height and head circumference at birth with the gap of the dental bud.

Material and Methods

An observational, descriptive correlational, retrospective and cross-sectional study was carried out, in the period between March 2020 and September 2021. The study population was made up of all the children enrolled in the second and third year of life in three Nursery Schools belonging to the Vedado Teaching Polyclinic in the Plaza de la Revolución Municipality, which constituted the universe of this study. The sample consisted of all the children who attended during the month of November and December 2020.

All children between 13 and 36 months of age, with Cuban nationality, as well as both parents, were considered as inclusion criteria. At the same time, children whose parents did not want to participate in the research were excluded, as well as those with congenital defects, syndromes or pathologies that affected the eruption, avulsion and/or extraction of primary teeth. All children were examined only once, in a single stage, by a single examiner. The data was also obtained from the standardized Clinical History of Children’s Circles, which were collected in a form created and validated for this purpose. The variables studied were:

Tooth eruption, which was described as erupted tooth or nonerupted tooth. Depending on whether or not the integrity of the gingival tissue has been broken, any part of its anatomy is visible in the oral cavity, regardless of the degree of eruption. Tooth bud lag was described as: no lag, delayed bud, or premature bud. According to what corresponds between the moment of the outbreak and the range of ages predicted for the eruption in the table of Chronology of the human dentition of Mayoral [10].

Birth weight was grouped into low weight, normal weight and overweight: according to the measurement made at the time of birth and recorded in the standardized clinical history of the Children’s Circle and guidelines established by the WHO [11]. Height at birth was grouped into short, normal and tall according to the measurement made at the time of birth and recorded in the standardized clinical history of the Children’s Circle and guidelines established by the WHO [11]. Head circumference was grouped into microcephaly, normocephaly, and macrocephaly. According to the measurement made at the time of birth and recorded in the standardized clinical history of the Children’s Circle and guidelines established by the WHO [11].For the processing of the information collected, the statistical software SPSS version 8.0 for Windows was used. For document management, the Zotero software was used, which allowed the categorical organization of documents and references in multiple formats. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were presented for each variable as appropriate. In addition, the influence of the various independent variables on the delay in the eruption of the primary dentition was evaluated using a logistic regression model, considering a significance level of 5%. The final report was made through Microsoft Office Word 2010. As it is a study of direct action on the human being, with psychic and social repercussions, it consists of ethical aspects, considering what was agreed in the second “Declaration of Helsinki”. The authorization of the directors of the Children’s Circles and the Informed Consent signed by the parents/guardians were obtained.

Results

Table 1 highlights the weight at birth and its relationship with the lag of the dental bud, where in the three categories of the pattern weight at birth the general trend is towards no lag. 12 underweight children were reported (7.18%); with a greater tendency to delay the dental bud (1.19%) than to its precocity (0.59%). In relation to normal weight children 144 (86.2%), we can see that it tends more to a premature eruption (16 cases 9.58%) than to delayed eruption (seven cases 4.19%). On the other hand, in patients with overweight in no case, evidenced eruptive delay. These differences were highly significant from a statistical point of view, with an association between low birth weight and delayed eruption of the primary dentition.

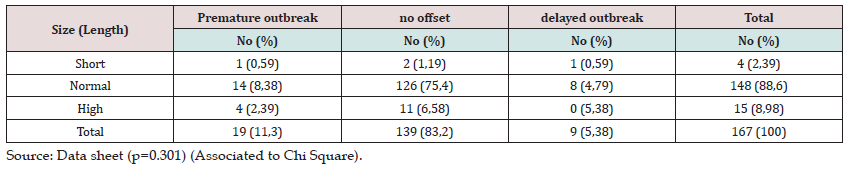

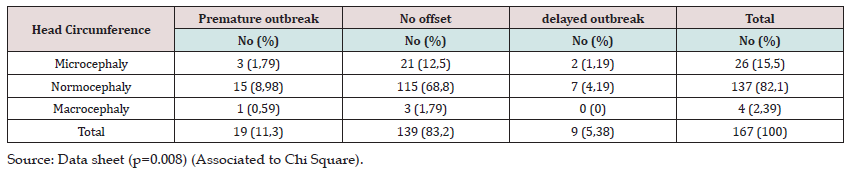

Table 2 provides an overview of height at birth and its relationship with dental bud lag, where in the three categories, the pattern of height at birth has a general tendency towards no lag (83.2%). In the cases of short stature (2.39%); in the same way, the premature and late outbreaks were presented (0.59%). In relation to children with normal length 148 (88.6%), we can see that it tends more to a premature outbreak (14 cases 8.38%) than to delayed eruption (eight cases 4.79%). patients with tall stature in no case, evidenced delay of the dental bud. In this sense, we did not obtain a statistical association between these variables. Regarding the evaluation of the head circumference, 82.1% of the children had between 33 and 37 cm of head circumference at birth (137 children). Microcephaly was detected in 26 children (15.5%) and macrocephaly in four children (2.39%). We found, in turn, that the delay in the dental bud prevailed in children with micro and normocephaly, two and seven, for 1.19% and 4.19%, respectively. Within the three groups, those cases that did not have a delay in dental bud predominated. These differences were statistically significant (Table 3).

Discussion

The results presented above reveal that there is an association between low birth weight and delayed outbreak. These conclusions coincide with the study by Pavičin I. et al. [12], Vargas [13]. Several studies [14,15] record results that support the criterion of the interrelation of these variables. Possibly this occurs because dental formation and calcification occurs from the prenatal stage, later the calcification of the incisor teeth (which are the first to emerge) ends and thus complete their eruption in the mouth [14]. Weight seems to influence the timing of primary tooth eruption, and the higher the birth weight, the sooner the first four teeth erupt. This is why most of the investigations [16-20] addressed the relationship between birth weight and the eruption of the first tooth, finding a statistically significant association in most cases. In this way, they classify it as: a determinant or predictor of the eruption chronology of the first milk tooth. Similarly, Khalifa [21] describe an inverse relationship, but when gestational age is corrected, no statistically significant differences were found. It seems to be concluded that children who weigh more at birth complete their dentition earlier, which is associated with hormonal factors due to their more accelerated development compared to normal weight children [22].

However, in this sense, Loayza [23] points out that the state of body weight at birth may have an influence on alterations in the order and delay in the chronology of eruption during the primary dentition stage, as well as an early mixed dentition with a high incidence of malocclusions. As we pointed out earlier, in our population, 7.18% are children who were born weighing less than 2,500g. Fact that we contrast with ; Contreras [2] who only found 1.3% with low weight, while other authors found higher distributions such as Ramos [24] 36.98% of children with <2500g. The latter ensures that all infants with low and high birth weight presented a normal rash; no infant with low birth weight presented delay and we found no association between weight and dental eruption (p=0.167), nor differences in the average ranges of the number of dental eruptions between infants with normal weight and high birth weight. In agreement with authors such as Andrade and Bezerra [22], they did not find any delay in children with low birth weight. Special attention should be paid to this last element, especially when we have a predominance in our sample of children over 2 years of age, since the author believes that dental emergencies at this age begin to be more conditioned by other factors. If we consider that, children with low birth weight generally tend to recover growth velocity between 2 and 3 years of age, during the recovery phase or recovery phase. This phase is characterized by a rapid increase in weight, length, and head circumference, with an accelerated growth rate, surpassing infants found in the general population at full term and normal birth weight. Catch-up weight growth is compensatory weight gain above normal standards for the specific age between birth and 24 months. Bearing in mind that recovery and delay in dental eruption in underweight children is even more evident up to 24 months of age [25]. When comparing this variable with other studies, it must be taken into account that the differences may also be due to the fact that when we speak of low birth weight, we are dealing with a complex entity, which includes premature infants (born before 37 weeks of gestation), term infants small for their gestational age, and neonates in which both circumstances are added, in which the most adverse outcomes tend to occur [11].

These three groups have their own subgroups, with elements associated with different causal factors and long-term effects. Understanding and differentiating the different categories and their subgroups is an essential first step in prevention. It is very important to clarify this starting point in the research method, as it can generate bias [11]. These results also allowed us to rule out the alternative hypothesis of the existence of a negative relationship between size and bud lag, since we did not obtain a statistically significant association, as did Contreras [2]. This is because with stricter parameters the number of infants with short lengths was small. However, Freixas [4] confirms that there is an association between these variables. In this regard, the author concludes that contrary to the results of previous studies, this could be due to a greater influence of postnatal development on dental growth, which is evident in children with smaller height at birth. Although the influence of size at birth also persisted to a lesser extent. Likewise, he considers that if age is to be estimated from erupted teeth, an incorrect estimate will be made in children of smaller birth height. Another element to consider is that our study is limited only to children between 13 and 36 months, where teeth in the posterior sector are erupting, whose eruption is more conditioned by the current size of the patient. Under this reasoning, we can find our theoretical support in what was stated by Karlberg, but published by Contreras [2] who cites that the majority of children (82.9% of the sample) of children born small for gestational age show a growth recovery during the first 6 months of age, consequently, if there were any influence of weight, length at birth, it could be evidenced in the earliest stages of the infant and in the first dental emergencies, which would correspond to the group of incisors. The current results reinforce the view that children with short length at birth may have erupted as many teeth as those of normal birth weight or even more. However, we found that Oziegbo [19] reported a positive relationship between size and dental emergence.

For his part, Contreras [2] compared his results with the study by Ounsted et al. He reported that children between the ages of 1 and 2 years had 0.1 more erupted teeth for every centimeter of height [26]. Like the weight at birth, most studies are aimed at relating the baby’s height and the time of the first eruption, turning out to be generally positive. We have an example of this in the research carried out by Pavičin I et al. [12], but this difference became non-significant when age was adjusted. In short, we can see that there is no unanimity in the criteria regarding height and its relationship with dental growth. The evaluation of the relationship with the dental bud should be based on nutritional assessment and not on weight and height separately, which would offer a much more precise view than the method used here. The intention to explore the relationship between dental gap and head circumference was given by the fact that this variable has been little addressed in research. Together with this, it is known that it is a useful tool for nutritional evaluation, except in the presence of hydrocephalus, decreases in head circumference are not unusual during the first days of life, while head molding and scalp edema are still being resolved; for that reason, head circumference should be re-measured 3 days after birth [2]. Regarding the evaluation of head circumference, an association was found between dental bud delay and microcephaly. In this sense, we can find our theoretical support in the fact that the head circumference is a reflection of the growth of the brain, it is an indicator of delayed development and identifies growth insufficiencies of nutritional origin [27]. This acquires even more relevance in our research when Rodríguez and Arletaz [28] state that the appearance of teeth in the oral cavity is associated with head circumference. However, Vejdani,et al. [29] did not show a positive relationship between the circumference of the baby’s head at birth and the time of the first eruption of the tooth. In the same way, Chalco [30] and Contreras [2] for the head circumference pattern, did not find an association with dental eruption, as well as Shuper et al, as reported by Contreras [2] in their research. Concluding that in our population the anthropometric factors that are potentially predictive in the eruptive gap of our population are: birth weight and head circumference at birth as opposed to height at birth.

References

- Çoban B, Kansu L, Dolgun A (2018) Timing and sequence of eruption of primary teeth in southern Turkish children. Acta Medica Alanya 2(3): 199–205.

- Contreras Ventocilla KM (2016) Relationship between the anthropometric patterns of the newborn and their deciduous dental eruption, Hospital EsSalud Marino Molina – 2016, Thesis to opt for the Professional Title of Dental Surgeon]. [Lima - Peru]: National University of San Marcos. Faculty of Dentistry EAP of Dentistry.

- Khaled Ghabani M (2017) The influence of weight and height on the eruption of primary dentition. University of Valencia, Cuba.

- Freixas Piñeiro Y (2016) Order and chronology of the primary dentition bud. Salvador Allende Polyclinic. Boyeros Municipality. 2015. [Thesis to opt for the Title of First Degree Specialist in Orthodontics]. [Havana. Cuba]: University of Medical Sciences of Havana. Faculty of Stomatology: “Raúl González Sánchez”.

- Šindelářová R, Žáková L, Broukal Z (2017) Standards for permanent tooth emergence in Czech children. BMC Oral Health 17(140): 8.

- K Vinod, Singh R, Suryavanshi R, Ashok Kumar, Singh RK, Ranjan R (2016) Eruption chronology of Primary Teeth in Garhwa district, Jharkhand, India. IAIM 3(5): 81–84.

- Carreño B, Cruz S de la, Piedrahita A, Sepulveda W, Moreno F, et al. (2017) Chronology of tooth eruption in a group of Caucasoid mestizos from Cali (Colombia). Rev Estomatol 25(1): 16–22.

- De Souza N, Manju R, Hegde AM (2018) Development and evaluation of new clinical methods of age estimation in children based on the eruption status of primary teeth. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 36(2): 185–190.

- Galician Arms LI, Rodriguez-Gonzalez S, Batista Gonzalez NM, Fernández- Pérez E (2019) Update on the order and chronology of the outbreak of the temporary dentition.

- Mayoral J, Mayoral G, Mayoral P (1984) Orthodontics. Fundamental principles and practice. 3rd Editorial Science and Technology, Havana, Cuba.

- (2017) Global nutrition targets 2025: low birth weight policy brief. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Pavičin IS, Dumančić J, Badel T, Vodanovic M (2016) Timing of eruption of the first primary tooth in preterm and full-term delivered infants. Bull Int Assoc Paleodont 8(1): 5.

- Vargas Dadalto EC, Wetler Marcona C, Martins Gomes AP (2018 ) Eruption of the first deciduous tooth in infants born pre-term: monitoring of 12 months. Rev Odontol UNESP 47(3): 168–174.

- Arteaga Flores GE (2017) Influence of current nutritional status and birth weight on the eruption of primary incisors in infants under one year of age treated at the 'El Porvenir' Polyclinic EsSalud-La Libertad. Thesis to opt for the title of professional Surgeon Dentist]. [Trujillo -Peru Antenor Orrego Private University, Cuba.

- Takashi Hanioka, Miki Ojima, Keiko Tanaka (2018) Association between secondhand smoke exposure and early eruption of deciduous teeth: A cross-sectional study. Tob Induc Dis 16(4): 15.

- Xiao Zhe Wang, Xiang yu Sum, Jun Kang Quan (2019) Effects of Premature Delivery and Birth Weight on Eruption Pattern of Primary dentition among Beijing Children. Chin J Dent Research 22(2): 131–137.

- Vahdat G, Zarabadipour M, Fallahzadeh F, Khani R (2019) Factors influencing eruption time of first deciduous tooth. Journal of Oral Research 8(4): 305.

- Shaweesh AI, Al-Batayneh OB (2018) Association of weight and height with timing of deciduous tooth emergence. Archives of oral biology 87(1): 168–171.

- Oziegbe EO, Adekoya-Sofowora C, Esan TA, Owotade FJ (2008) Eruption chronology of primary teeth in Nigerian children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 32(4): 341–345.

- Wu H, Chen T, Ma Q, Xu X, Xie K, et al. (2019) Associations of maternal, perinatal and postnatal factors with the eruption timing of the first primary tooth. Sci Rep 9(1): 1–8.

- Khalifa Afrin M, Reyad Atef ElG, Abd El-Mohsen MM (2014) Relationship between gestational age, birth weight and deciduous tooth eruption. Egypt Pediatr Assoc Gaz 6(2): 41–45.

- Arid J, Vitiello MC, Assed Bezerra da Silva R, Assed Bezerra da Silva L, Mussolino de Queiroz A, et al. (2018) Nutritional status is associated with permanent tooth eruption chronology. Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences 16(1): 7.

- Loayza Puga E (2017) Relationship of nutritional status and dental eruption of the upper central incisor in children 6-9 years of age in the I.E.E. 54085 Virgen de la Fátima of the district of Huancarama Peru, Technological University of the Andes. Faculty of Health Sciences. Professional School of Stomatology.

- Martínez-Ramos I, George Valles Y, Llópiz Milanés Y, Vidal B (2017) Characteristics of dental occlusion in children aged 4 and 5 years. MEDISAN 21(11): 3.

- Castro C, Mota EL, Cangussu MC, Vianna MI (2019) Low birth weight and the delay on the eruption of deciduous teething in children. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant 19(3): 701–710.

- Verna CB, Birte Melsen (2019) Orthodontic Aspects of Missing Teeth at Various Ages. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 199.

- Machado Martínez M (2009) Effects of Fetal Malnutrition on Growth and Development of the Craniofacial Complex. Thesis to qualify for the Scientific degree of Doctor of Stomatological Sciences, Santa Clara, University of Medical Sciences “Dr. Serafin Ruiz de Zárate Ruiz”. Villa Clara. Faculty of Stomatology.

- Rodriguez S, Arletaz MS (2011) The role of craniofacial skeletal growth in orthodontics. Monograph.

- Vejdani J, Naemi V (2011) Relationship between birth weight and eruption time of first deciduous tooth. J Res Dent Sci 7(4): 30–34.

- Jara Chalco B, Rodríguez Torres L (2008) Tooth eruption in relation to postnatal growth and development in children 18 to 29 months of age. Kiru 3(2): 70.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...