Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Case Report(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Posterior Indirect Adhesive Restorations: for Vital Posterior Teeth: Clinical Report Volume 1 - Issue 5

Dalenda Hadyaoui*, Imen Kalghoum, Nasri Sarra, Belhssan Harzallah, Mounircherif and Hajjemi Hayet

- Department of Fixed Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dental medicine, Monastir, Tunisia, Africa

Received: June 11, 2018; Published: June 19, 2018

*Corresponding author: Dalenda Hadyaoui, Department of Fixed Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dental medicine, Monastir, Tunisia, Africa

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2018.01.000123

Abstract

This article describes a case of compromised posterior vital teeth treated by indirect bonded ceramic restorations. A 24 year old female patient presented to the department of Prosthodontics. He was complaining about sensitivity in the posterior region. A comprehensive examination revealed failing amalgam restoration in the first molar with compromised cusps in the first molar. The treatment plan included indirect bonded ceramic restorations consisting of inlay and on lay on the concerned teeth.

Introduction

The daily use of indirect bonded restoration is very frequent in case of extended coronal destruction. The major treatment goal of compromised vital posterior teeth is minimal invasiveness based on adhesion which have made operator’s strategies completely changing in favor of minimally invasive bonded restorations. The principal advantage of those restoration is that preparation allows a greater preservation of healthy tissue than one for a

Clinical Report

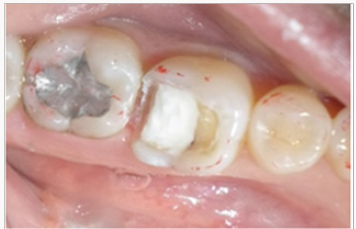

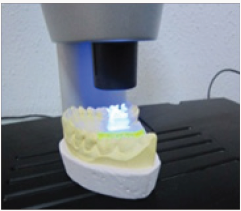

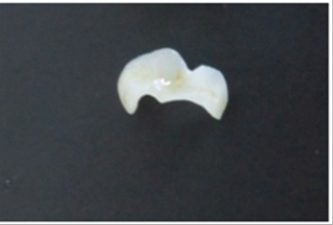

A 24 year old female patient presented to the department of Prosthodontics. She was suffering from a dental sensitivity in the posterior region. After a comprehensive examination, failing amalgams restorations in the first and right molar was evident and recurrent decay was noted. The second molar presented an MOD amalgam restoration whereas the first molar presented compromised cusps. The margins of the cavities were supra gingivally placed. During the first Appointment The failed amalgam, the recurrent decay were removed and temporary restorations were placed (Figure 1), and bonded ceramic restorations were planned. The first step was to mark the patient’s bite with an articulating paper. The preparation was, then, performed using diamond burs. The depth of the cavity was 1.5 mm with rounded occlusion axial angles .Undercuts was avoided with a cervico axial wall convergence of 1O° to 2O° (Figure 2). Dentin close to the pulp was covered with ionomer glass cement (Figure 3) and the margins were finished. The temporization was performed using a silicon index and acrylic resin (Texton) and cemented with a temporary a non eugenol cement (Figure 4). Full arch impression was taken using a silicone material (high viscosity washed with a low viscosity) (Figure 5). The restorations were manufactured from etcheable ceramic bulks (Cerec Vita Block1) via Cerec in Lab (Figures 6-8). For a secure bonding, the use of rubber dam was necessary. The thickness of the inlay and the on lay was recorded using a pair of tactile compasses and the thickness of the cuspal coverage in on lay was also measured.

The preparation surfaces were cleaned with special paste. The total-etching technique was used for the condition of tooth surfaces with 37% phosphoric acid gel for 30 seconds, then rinsed off. Resin luting agent is then applied to the preparation and the all ceramic restoration. The inlay-onlay was seated and excess luting material was removed. Gross excess resin can be removed after a spot cur. The restoration should be supported while the resin is cured. Light curing is then done in accordance with the resin manufacturer’s recommendations. The occlusion and the articulation were checked carefully after the inlay-onlay was luted in order to avoid fracture (Figure 8). Patient was recalled after 6 months for follow up in order to evaluate color, marginal adaptation, abrasion, secondary caries, fracture and post-operative pain.

Discussion

Indirect bonded all ceramic restorations are considered as an attractive alternative for Class I and II amalgam. They become highly recommended for treating vital posterior teeth especially when excessive width cavities and fractures may preclude the use of direct posterior composite restorations. They are stronger than composite resins with superior physical properties. Their clinical effectiveness is strongly related to the development of dental ceramics as well as bonding systems. [10,11]. In our case the use of lithium disilicate was extremely recommended. In fact, this material has been tested after the simulation of 5 years of wear. In comparison to other ceramics and even enamel in the study, the wear of lithium disilicate was very low, showing a sound surface without any wear of opposing dentition [12]. From an esthetic standpoint, the lithium disilicate material is very versatile. The opacity is controlled by the nanostructure of the material [13]. The restoration in our case, it was indistinguishable from the tooth being restored, after bonding. The morphologies of preparation can be different, depending on clinical situation, but there are some general rules to apply: Hence, the preparation should have smooth flowing margins to facilitate the fabrication of the restoration [14]. Box walls should converge in an occlusion direction. This will facilitate optical capture, Nevertheless, this rule was not completely respected. In order to achieve a balance between the preservation of tooth structure and strength of the material and in order to avoid fracture caused by insufficient material thickness, authors concluded that the idealized inlay preparation design requires a cavity depth of between 1.5 and 2 mm; cavity width of 1/3 the intercuspal distance; and a total occlusal convergence angle about 2O°and rounding of all internal line angles. Finally, to ensure a secure bonding with a durable result the margins should be supragingivally located and when an indirect restoration is demanded the cavities should not be extended below the enamel-cement joint [15,16].

Conclusion

Among all the treatment options available for aesthetic intracoronal restorations, ceramic inlay-onlay have performed reasonably well in clinical situations, when a vital posterior tooth is compromised because of wide preparations, compared with other materials. Nevertheless, they are extremely technique sensitive and the indication should be considered carefully, and further experience is necessary before they can be generally recommended for clinical use. There does not appear to be any one ceramic onlay technique or material which clearly provides clinical performance superior to the others, however the use of IPS max lithium disilicate offers new opportunities in restorative dentistry. The material’s strength and optical properties offer multiple options for achieving highly durable and esthetically pleasing restorations.

References

- Rocca GT, Krejci I (2007) Bonded indirect restorations for posterior teeth : From cavity preparation to provisionalization. Quitessence int 38(5): 371-379.

- Roulet JF, Soderholm KJM, Longmate (1995) Effects of treatment and storage conditions on ceramic/composite bond strength. J Dent Res 74(1): 381-387.

- Shen C, Oh WS, Williams JR (2004) Effect of post-silanization drying on the bond strenght of composite to ceramic. J Prosthet Dent 91(5): 453- 458.

- Monticelli F, Toledano M, Osorio R, Ferrari M (2006) Effect of temperature on the silane coupling agents when bonding core resin to quartz fiber posts. Dent Mater 22(11): 1024-1028.

- Silva RHBT, Ribeiro APD, Catirze ABCE (2009) Clinical performance of indirect - onlay for posterior teeth after 40 months. Braz J Oral Sci 8(3): 154.

- Barghi N, Berry T, Chung K (2000) Effects of timing and heat treatment of silanated porcelain on the bond strength. J Oral Rehabil 27(5): 407- 412.

- Fligor J (2008) Preparation design and considerations for direct posterior composite inlay-onlay restoration. Practical procedures and aesthetic dentistry 20(7): 413-419.

- Felden A, Shmalz G, Federlin M (1998) Retrospective clinical investigation and survival analysis on ceramic inlays and partial ceramic crowns: results up to 7 years. Clin Oral Invest 2(4): 161-167.

- Saridag SS, Sevimay M, Pekkan G (2013) Fracture resistance of teeth restored with all-ceramic inlays and onlays after eight years. Oper Dent 38(6): 626-634.

- Kramer N, Frankenberger R (2005) Clinical performance of banded leucite-reinforced glass ceramic inlays and onlays after eight years. Dent Mater 21(3): 262-271.

- Kramer N, Ebert J, Petschelt (2006) A Ceramic inlays bonded with two adhesives after 4 years. Dental materials 22(1): 13-21.

- Hopp CD, Land MF (2013) Considerations for ceramic inlays in posterior teeth; a review. Clinical cosmetic and investigation Dentistry 18(5): 21- 32.

- Fligor J (2008) Preapration design and considerations for direct posterior composite inlay-onlay restoration. Pratical procedures and aesthetic dentistry 20(7): 413-419.

- Abraham S, Attur K, Singh SKN (2011) Aesthetic Inlays. International journal of dental clinics 3(3): 62-64.

- Thompson MC, Thompson KM, Swain (2010) The all-ceramic, inlay supported fixed partial denture.Part 1.Ceramic inlay preparation design: a literature review. Aust Dent J 55(2): 120-127.

- Ahlers MO, Land MF (2013) Considerations for ceramic inlays in posterior teeth: a review. Clinical cosmetic and investigational Dentistry 5: 21-32.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...