Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Case Report(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Necrotizing Fasciitis in Children Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Procedures, Treatment Methods, and the Outcome Volume 6 - Issue 4

Hakobyan GV1* Mkrtchyan NM2, Hovhannisyan AR3, Asatryan AM4 and Khachatrayn GA5

1Head of the Department of Surgical Stomatology and Maxillofacial Surgery, Yerevan State Medical University, Armenia

2Assistant Professor, Department of Surgical Stomatology and Maxillofacial Surgery, Clinic of Pediatric Maxillofacial Surgery and ENT, Muratsan University Hospital Complex, Armenia

3Associate Professor, Department of Plastic Surgery Yerevan State Medical University, Armenia

4Resident, Department of Surgical Stomatology and Maxillofacial Surgery, Yerevan State Medical University, Armenia

5Head of the Department of Dental Professional and Continuing Education, Yerevan State Medical University, Armenia

Received:August 05, 2021 Published: August 16, 2021

*Corresponding author: Gagik Hakobyan, Head of the Department of Surgical Stomatology and Maxillofacial Surgery, Yerevan State Medical University, Armenia

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2021.06.000243

Abstract

Background: Necrotizing fasciitis is a potentially life-threatening soft tissue infection, characterized by necrosis of the fascia, subcutaneous tissue, adipose tissue and can be fatal. NF is most common in immunocompromised hosts but may also occur in healthy patients without apparent antecedent injury. It is usually caused by either Group A streptococci or a polymicrobial, synergistic infection. The case that we present is unique in the Republic of Armenia, necrotizing fasciitis of the face in a child.

Methods: We report the case of a 3,5-year-old children who were treated for NF in our unit, inclusive, were reviewed retrospectively. Information recorded included medical history, clinical characteristics, diagnostic procedures, treatment methods, and the outcome.

Results: The essence of the treatment was to prevent further development of necrosis, taking the child out of the state of general intoxication, in connection with, early surgical debridement, anti-intoxication, antibacterial therapy were carried out in several stages. In result , auto transplantation by full thickness skin autograft has been done, maintaining the aesthetic appearance of the wound.

Conclusion: Because necrotizing fasciitis is a surgical emergency, the patient should be admitted immediately to a surgical intensive care unit, where the surgical staff is skilled in performing extensive debridement and reconstructive surgery. Despite the fact that it is rare in children, according to our data, it turned out that the reason for the penetration of microorganisms may be an incomplete injection. Clinicians should be aware of these infections, as early treatment can increase survival.

Keywords: Necrotizing fasciitis; debridement; children; soft-tissue infection

Introduction

Necrotizing fasciitis is a potentially life-threatening soft tissue infection, characterized by necrosis of the fascia, subcutaneous tissue, adipose tissue and can be fatal [1]. In the case of necrotizing fasciitis, the mortality rate is 15-40%. It occurs in all age groups, but the majority of patients are under 40 years of age, there is no difference between genders or race. Because it is rare in children (prevalence 0.02%), it is often misdiagnosed as cellulite, which delays the correct diagnosis and increases the risk of fulminant course and the risk of high mortality [2]. In 1871, U.S. army surgeon named Joseph Jones first described the disease during the Civil War. He called it “hospital gangrene”, in 1924, Melanie studied 20 cases of “streptococcal gangrene”. He was the one to note that subcutaneous necrosis is the hallmark of necrotizing fasciitis. It predominantly affects the tissues of the abdominal wall, the perineum and the extremities, but can be seen in the maxillofacial region also. The term “necrotizing fasciitis” was coined by Wilson in 1952 and has gained wide acceptance [3]. Necrotizing fasciitis of the neck is rare and usually occurs secondary to dental infection, gingivitis, or pulpitis. However, any infection that can cause deep neck infection can cause necrotizing fasciitis. It is characteristic that everything starts with a small injury and there is no chronic disease or other pathology [4]. Local early signs for necrotizing fasciitis are edema, induration and erythema. Skin necrosis is a late sign [5]. The prognosis depends upon accurate diagnosis and early surgical debridement: This is often difficult due to the lack of initial physical signs [6]. NF is most common in immunocompromised hosts but may also occur in healthy patients without apparent antecedent injury. It is usually caused by either Group A streptococci or a polymicrobial, synergistic infection. There are also emerging monomicrobial causes, including those caused by non-Group-A Streptococci such as groups B, C, and G. Early clinical findings are typical for septicemia: fever, severe pain, tachycardia and elevated white blood count.

Case Report

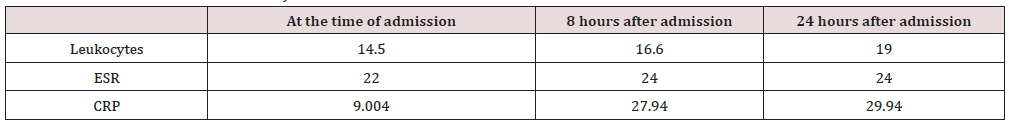

The case that we present is unique in the Republic of Armenia, necrotizing fasciitis of the face in a child. The incident occurred with a 3.5-year-old child, whose dentist tried to administer anesthesia to treat pulpitis of the 84th tooth. There were probably deviations in this (Contamination of the needle tip by oral microorganisms or deviation of injection at right anatomical zone, deviation from the correct anatomical injection site). A 3.5-year-old child was admitted to the hospital with complaints of pain in the right cheek area, edema, fever, weakness, loss of appetite, diarrhea, multiple vomiting (Figure 1). At the primary examination, the appearance was pale, rapid breathing, pulse 130-150 beats per minute , blood pressure 30/10 - 40/20 mm Hg, blackout (darkening of consciousness), from temperature to 39, severe diarrhea: vomiting. Local, the face of the child looks so asymmetrical, due to edema of the lower right third of the face, which has spread to the submandibular region. The palpation to the specified area is soft, the skin is does not fold, less painful, the skin is bluish-red, the submandibular lymph nodes are slightly enlarged (Table 1). During the examination of oral cavity, there was a carious cavity of 84 teeth, the probing was painless, no fluctuations in the area were observed. Slightly hyperemic swollen mucous membrane at the injection site (Figure 2). According to the parent, the complaints have arisen within the last 18 hours , a day ago, the dentist diagnosed pulpitis of 84 teeth in a child, in connection with which infiltration anesthesia was carried out: approximately 1 carpul UBISTESIN FORTE 4% of the drug .In the following hours, the child’s condition continued to be extremely severe, CRP, leukocytes, ESR levels increased (8 hours after admission) blood pressure 60/40 mm Hg, pulse rate 120-140 beats per minute, blackout (darkening of consciousness), an increase in body temperature up to 39.2°C.

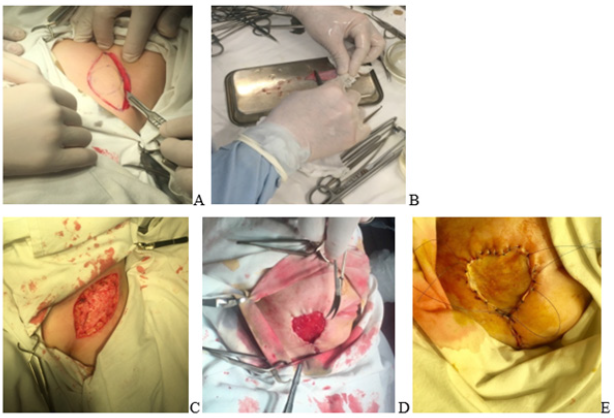

Figure 1: A Child at the time of admission, B: 8 hours after admission, C,D: Child - 8 hours after the first intervention, E,D: Necrectomy at the level of visible healthy tissue after 24 hours.

Figure 2: AB: The appearance of the wound on the 5-10th day – fibrin and necrosis foci C: Applying of xeroform bandages for the next 1-10 days.

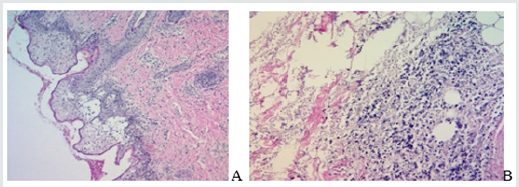

After 8 hours, the lesions of necrosis turned blue-violet, the swelling spread to the entire neck and chest. As a result, toxic shock was diagnosed, post-injection necrotizing fasciitis of the right buccal and submandibular region. As indication of life , it was decided to do an urgent surgery. Two incisions were made in the right buccal region under general anesthesia. A connection was established between the two incisions, drained, as a result of which the interstitial pressure decreased. After the intervention, the child’s condition remains extremely severe, but the pronounced tachycardia decreased to 100 beats per minute, the consciousness darkened due to drug-induced sleep, the skin turned pale, the body temperature up to 37.2-38.2 °C. Over the next 24 hours, a demarcation zone was observed around the site of necrosis, and the skin turned black. At the next stage, it was decided to perform necrectomy at the level of visible healthy bleeding tissues, with the most conservative approach. Under general anesthesia, an intervention was performed along the demarcation zone, the skin was removed along with subcutaneous tissue approximately 4 × 6 cm. After the intervention, the child’s condition was assessed as moderate, clear consciousness, sometimes temperature up to 37.2. Antibacterial, detoxification treatment continued, leukocytosis persists, ESR and CRP levels are still high. A bacteriological study of the products taken from the wound was carried out; as a result, ß -hemolytic streptococcus was found. The study was carried out on the following days before transplantation in order to prevent the development of infection with other microorganisms. In the following days, the wound was bandaged by removing fibrin, focus of necrosis and applying xeroform banda. The removed tissues were sent for pathohistological examination, according to the results of which, according to the microscopic description- аsymmetric vascular hemorrhages were observed in the vessels of the skin, underlying soft, fatty and muscle tissues, thrombotic formations in some vessels, extensive necrosis fields with diffuse moderate inflammatory infiltration, microcerebral hemorrhage, epidermolysis (Figure 3A & 3B).

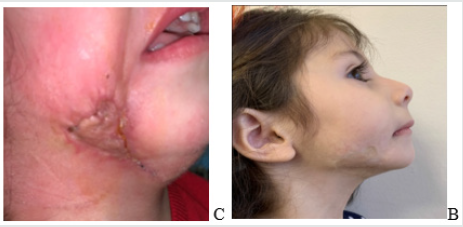

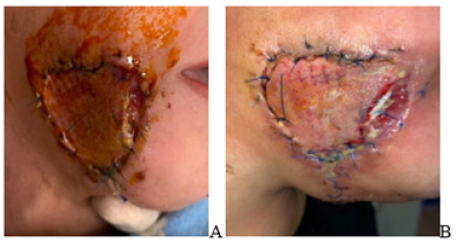

Later, continued antibacterial (Vancomycin, Cipro-Tech 0,2%), anti-intoxication treatment., during which one should pay attention to wound necrectomy, the fact of the presence of a completely healthy wound surface, which was observed on 16-20 days of treatment (Figure 4A,B,C). Next step is important- it’s wound healing, because this zone is a transition area from buccal to submandibular region, excessive stretching can cause the mouth to be stretched with the corresponding side, plastic with local tissues was not appropriate due to the size of the area: In collaboration with plastic surgeons, an operation was performed on the 22nd day of disease - wound healing with autograft with left-sided skin graft in a child (one of the most expedient options (Figure 5). After 5 days the first wound bandaging was performed, during which the edges of the wound in the corner of the mouth were removed, from a crying of baby, during which the muscles tense. The child has neither functional nor psychological problems, does not restrict the movements of the mouth and jaws. There is a certain unevenness of the skin in the repair part of the defect. After the incident other teeth were treated and removed, but there were no complications (Figure 6).

Figure 5A,B,C ,D,E: Taking a full thickness skin autograft from the left inguinal area, repair of the defect with an taken autograft.

Figure 6A,B: The appearance of the wound 5 days after transplantation, the bandage was removed, the edges were removed in a certain area.

Discussion

The described clinical case - necrotizing fasciitis - is a rare disease in children, also known as hemolytic streptococcal gangrene, acute cutaneous gangrene, purulent fasciitis, nosocomial gangrene, synergistic necrotizing cellulite. Necrotizing fasciitis in children is usually monomicrobial, most often due to the gas produced. The infection is estimated to occur in 13 of 100,000 hospitalized children [7]. Diagnosis is difficult because it is necessary to distinguish between noma and cellulite. They differ from each other in their epidemiological, clinical and etiopathological characteristics. Noma is considered an opportunistic disease, but the cause is unknown, the pathogenesis is complex, multifactorial, including interactions between local polybacterial infections, malnutrition, immunosuppression, systemic bacterial or viral infections. For noma is typical to involve deep layers up to the bone. Cervicofacial necrotizing fasciitis is a rare, rapidly progressive polymicrobial infection that infects the skin and subcutaneous tissue, leading to tissue destruction [8]. In the pathogenesis of necrotizing fasciitis, synergistic interactions of streptococci, staphylococci, bacteroids, clostridia, Klebsiella occur. It is usually followed by odontogenic infection, surgery, or post-accident trauma, but not necrotizing stomatitis (as in the case with noma). It is characterized by an acute inflammatory reaction, edema, local venous-arterial thrombosis, resulting in ischemic necrosis and sludging of damaged tissues (Figure 7). Noma often begins as necrotizing gingivitis, progressive necrotizing periodontitis, and then necrotizing stomatitis. Although noma and necrotizing fasciitis has many similar characteristics, there are many cases in which it may be associated with muscle necrosis, but there is no destructive perforation in the entire thickness of the cheeks and lips. In cases leading to noma, the source of polybacterial infection in the chain is primary necrotizing gingivitis/necrotizing periodontitis, which progresses to necrotizing stomatitis. Malnutrition, weakened immune system, and strong inflammatory reactions are some of the factors that can lead to necrotic stomatitis. Diabetes, immunosuppression, and malnutrition are some of the risk factors for necrotizing fasciitis [9].

And since no strain has been found in our case that could cause necrotizing gingivitis or necrotizing stomatitis, the diagnosis of noma has been definitively denied. Cellulite is a bacterial infection of the deep layers of the skin և subcutaneous tissue: It is most often caused by S. pyogenes և S. aureus. Bacteria can enter the skin through scratches on healthy skin, while the hematogenous route is more common in immunocompromised patients[10]. Cellulite is often manifested by redness, swelling and pain in damaged tissues. Injuries are often hot and are associated with lymphangitis. Often accompanied by systemic complaints such as fever and pain. Injuries are often accompanied with lymphadenopathy: Erysipelas is originally described as a butterfly-shaped mass on the face due to the production of an exotoxin, not by the streptococcus itself. The infection does not affect deeper subcutaneous tissue, although it may be associated with tissue swelling [11]. Cellulite is a unique manifestation of haemophilus influenzae that occurs in children under 1 year of age. It rarely occurs on the limbs, the majority (74%) are located in the buccal, periorbital and neck region. Cellulite on the face of newborns is often manifested by an acute fever with unilateral assertion, fever and pain, which may progress to a purple color. Aspiration of the point of maximum swelling usually leads to the appearance of organisms. Cellulite on face is often associated with bacteremia, 10-20% of children may have a secondary injury, including meningitis [12]. In contrast to cellulite, factors suggestive of necrotizing fasciitis include pain that does not match physical examination results, rapid spread of swelling, and bulla formation.

The most common cause of necrotic fasciitis around the head and neck is primary odontogenic or after removal infection. Infection of the tonsils, salivary glands, otogenic-dermatological infections are other rare causes. Patients often suffer from systemic diseases such as diabetes, alcoholism, malnutrition or chronic kidney failure [12]. Necrotic fasciitis in its early stages can be misdiagnosed as a soft tissue infection, such as cellulite or infected erysipelasis (benign). Relatively mild clinical signs may hide severe underlying necrosis. This can delay the necessary surgery, which can be life threatening: Necrotizing fasciitis usually begins at the site of an often-invisible injury, which can be a small puncture wound, a blunt injury, or a surgical scar. A study by Wong clarified the clinical picture of patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Their patients usually complained of severe pain, swelling, and fever. The only initial signs were pain, erythema and hot skin. In addition, the most common initial symptom was pain that did not correspond to clinical symptoms. Other studies have shown that at this early stage it is similar to flu. Lymphangitis and lymphadenitis are usually absent. The intermediate stage of necrotizing fasciitis, according to studies by Wong and other researchers, is characterized by the formation of small bullas. The presence of such bullae, filled with serum fluid, was an important diagnostic feature. Late symptoms in patients include large hemorrhagic bullae, skin necrosis, and crepitation. Children usually have fever, irritability, swelling of the affected area, erythema and pain, disproportionate clinical data. In newborns, it can be difficult to localize pain. Treatment for necrotizing fasciitis begins with early diagnosis. Unfortunately, the diagnosis is often delayed due to the lack of obvious signs and symptoms. Some have tried to develop tests to predict necrotizing fasciitis. Wong և others proposed the LINEREC diagnostic evaluation system (a laboratory indicator of the risk of necrotizing fasciitis) based on a number of laboratory tests, including the number of leukocytes, electrolytes and C-reactive proteins, which had a positive prognosis value of 92.0% and negative predictive value of 96.0% [1].

More research is needed to assess whether such systems are useful. Other methods, such as a frozen section biopsy, CT (computerized tomography), MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), and ultrasound (ultrasound scan ), can help with the diagnosis, but they should never be delayed. CT scan reveals gas accumulated in the tissues, high level of CRP in the blood and leukocytosis. Treatment includes early wound healing, broadspectrum antibiotics for polymicrobial infections (usually penicillin or ampicillin, clindamycin և aminoglycoside), hemodynamic support, re-examination of wound healing (usually within 24- 36 hours), and nutritional support. In addition, seeds should be taken from blood and from infected tissues. Another treatment that is still controversial is hyperbaric oxygenation, which can help with treatment and prevent further side effects. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been shown to be effective in limited studies of less severe infections with toxic shock [12]. A study by Wong and al. researchers found that the only factor that could affect survival in logistic regression analysis was surgical delay. This is evidenced by numerous studies that show that early treatment is associated with significant reductions in mortality.

Conclusion

Necrotizing fasciitis is rare in children. It should also be noted that children cannot provide a complete history of pain, anxiety, which parents may perceive simply as toothache or fever as an acute respiratory infection, before the onset of primary clinical signs. In our case, it has been proven that rapid intensive therapy, antibiotic therapy, and early surgical debridement can lead to complete recovery. Clinicians should be aware of these infections, as early treatment can increase survival.

Conflict of Interest and Financial Disclosure

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest and there was no external source of funding for the present study. None of the authors have any relevant financial relationship(s) with a commercial interest.

Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

References

- Bisno AL, Stevens DL (1996) Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissue, N Engl J Med 334(4): 240-245.

- Viktoria A P feifle, Stephanie J Gros, Stefan Holland-Cunz Alexandre Kämpfen (2017) Necrotizing fasciitis in children due to minor lesions. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports 25: 52-55.

- Marioni G, Rinaldi R, Ottaviano G, Marchese-Ragona R, Savastano M, et al. (2006) Cervical necrotizing fasciitis - A novel clinical presentation of Burkholdena Ceparia infection. Infect 53: 219-222.

- CH Wong, HC Chang, S Pasupathy, LW Khin, JL Tan, et al. (2003) Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 85(8): 1454-1460.

- G Darmstadt (2003) Subcutaneous tissue infections and abscesses in Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. S Long, L Pickering, C Prober (Eds.), Churchill-Livingstone, New York, N, USA, 2nd edition pp. 449-457.

- MA Jackson, J Colombo, A Boldrey (2003) Streptococcal fasciitis with toxic shock syndrome in the pediatric patient. Orthopaedic Nursing/National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses 22(1): 4-8.

- John Rausch, Marc Foca (2011) Necrotizing Fasciitis in a Pediatric Patient Caused by Lancefield Group G Streptococcus: Case Report and Brief Review of the Literature. Case Reports in Medicine.

- Anisha Maria, K Rajnikanth (2010) Cervical necrotizing fasciitis caused by dental infection: A review and case report. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 1(2): 135-138.

- Charles van Niekerk , Razia AG Khammissa, Mario Altini, Johan Lemmer, Liviu Feller (2014) Noma and Cervicofacial Necrotizing Fasciitis: Clinicopathological Differentiation and an Illustrative Case Report of Noma. Aids Research And Human Retroviruses 30(3): 213-216.

- Aisha Sethi (2013) Bacterial Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Tropics, Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease, 9th Edition pp. 515-518.

- Ali Banki, Frank M Castiglione (2016) Infections of the Facial Skin and Scalp. Head, Neck, and Orofacial Infections, A Multidisciplinary Approach pp. 318-333.

- Ericka King, Robert Chun, Cecille Sulman (2012) Pediatric cervicofacial necrotizing fasciitis: a case report and review of a 10-year national pediatric database, Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138(4): 372-375.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...