Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Has Covid-19 Global Pandemic Impacted Antibiotic Use Among High Caries Risk Children? Evidence from Preventive Oral Health Care Setting in Sri Lanka Volume 7 - Issue 3

Irosha Perera1*, Suranga Dolamulla2, Chandra Herath3 and Manosha Perera4

- 1Preventive Oral Health Unit, National Dental Hospital (Teaching), Ward Place, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

- 2Director, International Health, Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka Department of Health Histories, University of York, UK

- 3Division of Pedodontics, Faculty of Dental Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.

- 4Alumnus, School of Dentistry and Oral Health, Griffith University, Gold Coast, QlD

Received: March 14, 2022; Published: March 23, 2022

*Corresponding author: Irosha Perera, Preventive Oral Health Unit, National Dental Hospital (Teaching), Ward Place, Colombo, Sri Lanka

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2022.07.000263

Abstract

Background: Covid-19 global pandemic ravaged health and wealth of people in developed and developing countries crippling health care systems and economies across the globe. Despite countries resuming normalcy powered by mass scale immunization drives after battling sinister waves of Covid-19 epidemics, its pervasive impact is yet to be fully explored. Early childhood caries (ECC) ranks top among the leading chronic childhood diseases especially among high risk toddlers and children in developing countries and disadvantaged minority groups in developed countries. Covid-19 induced interruptions into preventive oral health care services compounded by lock-down related life-style changes fostering unhealthy dietary patterns were common scenarios in those troubled times. Against this backdrop, present study attempts to explore and expound the impact of Covid-19 milieu on antibiotic use among high caries risk toddlers and children attended a public preventive oral health care unit.

Method: The study design was retrospective, hospital based, and the study setting was the Preventive Oral Health Unit of the National Dental Hospital (Teaching) a premier, multispecialty, tertiary care public dental hospital in Sri Lanka. The patient statistics data base for the year 2019 was used as the pre-Covid-19 baseline, compared with the years of 2020 and 2021 affected by Covid-19 global pandemic. The proportionate episodes of child-patient visits needed antibiotics for dento-alveolar infections to the total number of child-patient visits from 1st January to 31st December each year and during peak Covid-19 periods in 2020 and 2021 were compared. Data were entered and analysed using SPSS-21 Statistical Software Package. Frequency distributions and descriptive statistics were used for data presentation. The means were compared by independent sample T-Test, Mann-Whitney U test and one-way ANOVA test of statistical significance after assessing the distribution of data by Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro- Wilk tests of normality.

Results: In overall, there was a proportionate increase in presentation of symptomatic dento-alveolar infections to total visits during the peak periods of Covid-19 waves in 2020 & 2021 compared to respective months of pre-Covid 19 era (year 2019). The mean percentage proportion of prescribing antibiotics to total number of visits was 18.07 for the year 2019 whilst it was 31.25 and 32.73 for the years 2020 and 2021 respectively. Those indicated increased use of antibiotics in Covid-19 mileu compared to the baseline year. However, those differences did not reach statistical significance (p=0.078) in 3-year comparison. Nevertheless, there was a statistically significant increase (p=0.006) in percentage proportion of prescribing antibiotics to overall visits in 2021 compared to 2019 however, the increase of prescribing antibiotics in 2020 compared to 2019 did not reach statistical significance (p=0.319). Furthermore, comparisons of antibiotic use in months of peak Covid-19 epidemic periods in 2020 and 2021, with corresponding periods of pre-Covid 19 era showed statistically significant increases (p=0.007 and p=0.0001).

Conclusions: As evident from the findings, Covid-19 milieu in its peak periods, significantly impacted the use of antibiotics for dento-alveolar infections of high risk toddlers and children favouring an over- use, which could be attributed to interruptions to proactive preventive oral health care service utilization. As overuse of antibiotics could aggravate the existing global public health threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), this becomes a cause of concern. However, further studies are warranted to confirm the evidence generated from this study

Introduction

Covid-19 global pandemic declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11th March 2020 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) ravaged health and wealth of people in both developed and developing countries crippling health care systems and economies across the globe [1]. New waves of Covid-19 caused by novel strains of highly infectious strains of SARS-Cov-2 virus such as Omicron designated as a “variant of concern” by the WHO affected many countries [2,3]. Despite countries resuming normalcy after battling sinister waves of Covid-19 with mass scale immunization drives encountering many challenges [4], its pervasive impact is yet to be fully explored. Early childhood dental caries (ECC) ranks top among the leading chronic childhood diseases is frequently prevalent but infrequently treated [5,6]. Nevertheless, providing paediatric dental treatment became increasingly challenging in Covid-19 milieu and all guidelines issued in this regard revolved around minimizing aerosol generation procedures (AGP) in providing regular dental treatment among paediatric patients [7]. Consequently, triaging and treating only emergency and urgent cases were emphasized and use of non-invasive or minimally invasive caries management techniques were recommended [7-10], remained preferable choices for clinical practice of post Covid-19 period as well [11]. In contrast, aerosol generating procedures, extractions and use of general anaesthesia or sedation became common procedures in the post lock-down period by some paediatric dentists [12].

Qualification of Early Childhood Caries (ECC) to be treated as emergency cases could be attributed to the fact that the disease affects vulnerable populations such as preschool children with the propensity of presenting with late sequalae of pulpitis and periapical infections with pain and swelling [13]. Nevertheless, oral health care provision as well as Paediatric dental care services has been significantly impacted by the inevitable dental practice modifications induced by Covid-19 global pandemic [12,16-18]. Nevertheless, an international survey on the Covid-19 pandemic and its global impact on dental practice painted the portrait of a contrast picture of a lesser impact on oral health care provision except reduction in access to routine dental care due to country specific temporary lock down periods [19,20]. Nevertheless, this impact was profound for children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who already experience higher levels of dental disease and disadvantage in accessing dental care [17]. Overall reductions in children’s’ dental visits, overwhelming predominance of exclusive emergency treatment provision, deferment of routine and preventive oral health care became the norms in Covid-19 milieu [12,16-18]. Despite, the necessity of deferment and restriction of dental service provision aimed at controlling the risk of transmission of COVID-19 in the dental setting, its impact on oral health of people would be extensive [17]. Provided the chronic, progressive nature of dental disease, the deferral of necessary dental care seemingly aggravates poorer oral health and long-term oral health problems of people [17].

Early childhood dental caries (ECC) and its late sequalae such as pulpitis and dento-alveolar abscesses garnered recognition as leading unmet treatment needs of children [5] thus disproportionately affecting disadvantaged populations [21]. It is rational to argue that prolonged interruptions to preventive oral health care services due to Covid-19 transmission control strategies has increased the existing burden of ECC. The importance of early preventive oral health care visits by toddlers to prevent and reduce the burden of ECC is already known [20]. However, availability of and accessibility to preventive oral health care services became challenging in Covid-19 milieu [15,17-18]. Furthermore, there is compelling evidence to support the negative impact of Covid-19 on preventive oral health care utilization by high risk groups whilst raising the proportion of emergency visits due to aggravated dental diseases [17,18]. Furthermore, as preventive oral health care provision is essential to reduce the burden of late sequalae of dental caries among high risk toddlers and children, the need for novel models of service provision in Covid-19 milieu underpinned by physical and social distancing has been highlighted [17].

Acute and chronic pulpitis and dento-alveolar infections manifested as pain and swelling of late sequalae of untreated dental caries in deciduous (primary teeth) is a common presentation for emergency paediatric dental care [22]. Common mode of treatment for late sequalae of dental caries comprised of prescribing antibiotics, incision and drainage of abscesses, providing pulp therapy (pulpotomy or pulpectomy) or extraction under general anaesthesia in advanced cases. Furthermore, prudent and proper use of antibiotics in paediatric dentistry stipulates prescribing antibiotics subsequent to systemic evidence of spread of infection such as facial swelling, radiological evidence of pathology and after a thorough clinical examination [23]. Pulpitis, apical periodontitis, draining sinus tract, abscess, and acute facial swelling of dental origin need rational use of antibiotics to ensure antibiotic stewardship given the rise of antibiotic resistant microorganisms and adverse drug reactions and interactions [23]. However, studies reported increased dental antibiotic prescribing in oral health care provision during Covid-19 global pandemic for low income populations with high incidence of toothache and odontogenic infections in Canada [24], National Health Service (NHS) in the UK [25] as well as in the Australia under the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefit scheme (APBS) [26]. The global public health threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) attributed to surge of multidrug resistant microbes is well-known [27]. According to the findings of global burden of antibacterial resistance study on deaths and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) attributable to and associated with bacterial AMR for 23 pathogens and 88 pathogendrug combinations in 204 countries and territories in 2019, there were an estimated 4·95 million (3·62-6·57) deaths associated with bacterial AMR in 2019, including 1·27 million (95% UI 0·911- 1·71) deaths attributable to bacterial AMR [28]. AMR is a leading cause of death across the globe, with the highest burdens in lowresource settings [28]. Both Covid-19 global pandemic and AMR posed pervasive catastrophe to public health systems across the globe as a double- edged sward. Overuse and misuse of antibiotics could be considered as a key driver for development of AMR [29,30] whilst their rational use has garnered recognition as a fundamental precaution in this regard [30]. Overuse of antibiotics has potentiated the extraordinary genetic capacities of microbes to exploit every source of resistance genes and every mode of horizontal gene transmission to develop multiple mechanisms of resistance for almost all antibiotics used clinically, agriculturally, or otherwise [31]. A previous study reported the contribution of preventive oral health care to reduce the incidence of dento-alveolar infections among high risk children [32]. Accordingly, 77.3% of children who attended with untreated dental caries were prevented from progressing into symptomatic dento-alveolar infections in the year 2017 by the stringent application of the preventive oral health care package. It is well-known that pulpitis and dento-alveolar infections were a common cause for emergency visits for oral health care among children in Covid-19 milieu [32]. However, it is not clear how such visits impacted antibiotic use in the management of late sequalae of untreated dental caries among children. Such baseline information is crucial for evidence-based update of the guidelines in paediatric dentistry in the present global pandemic and in future ones. Against this backdrop, we aim to investigate the impact of Covid-19 on use of antibiotics in treating dento-alveolar infections among high risk toddlers and children attended the Preventive Oral Health Unit (POHU) of National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted to explore and expound the use of antibiotics for the management of dentoalveolar infections among high risk urban toddlers and children attended the POHU of National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka. The patient statistics were accessed for the years 2019 (pre- Covid-19) and Covid-19 eras (2020 and 2021) from 1st of January to 31st December for each year.

Study Setting

The Preventive Oral Health Unit (POHU) which caters to the high caries risk toddlers and preschool children by a geographically targeted need and demand based model provided the study setting.

Data Sources

Performance statistics data of the preventive dental clinic conducted by POHU for the years 2019,2020 and 2021from 1st January to 31st December of each year were accessed from the data base. Data on number of episodes of prescribing antibiotics for toddlers and children presented with dento-alveolar infections per each month was collected with the total number of visits. Proportionate episodes of prescribing antibiotics were calculated by taking the total episodes of prescribing antibiotics of the given month as the numerator and the total cumulative visits of the month as the denominator converted to a percentage.

Statistical Analysis

Distribution of variables were assessed for normality by using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk test. Independent sample T-test, Mann-Whitney U-Test and one-way ANOVA were used to compare mean proportionate episodes of prescribing antibiotics to total visits at the statistical significance of p < 0.05. Data were entered and analysed using SPSS-21 Statistical Software Package. Comparisons were made for the 3-year (2019,2020 and 2021) as a whole, years, baseline (pre-Covid- 19) 2019 with Covid-19 stricken years: 2020 and 2021 as well as peak Covid-19 periods: April to July 2020 and October to December 2020 and May to September 2021 respectively with the corresponding periods of the baseline year.

Results

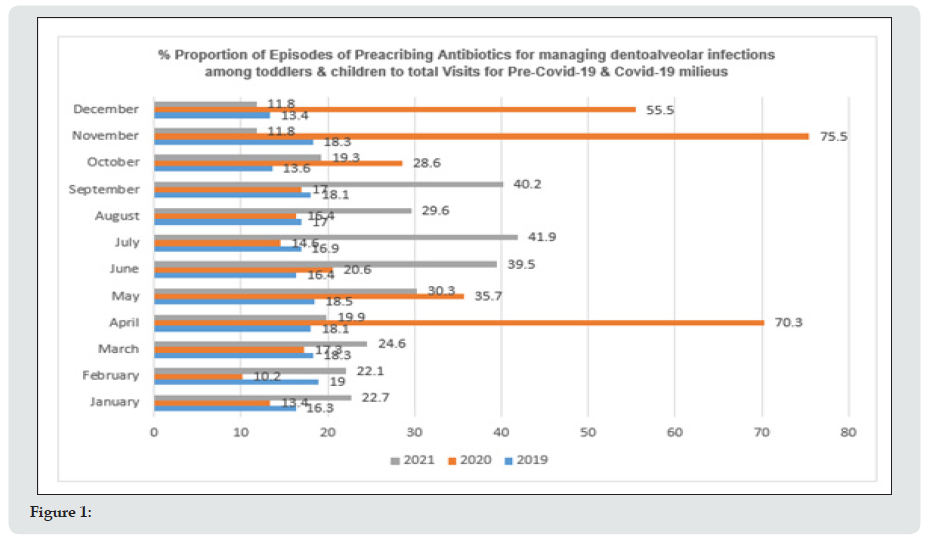

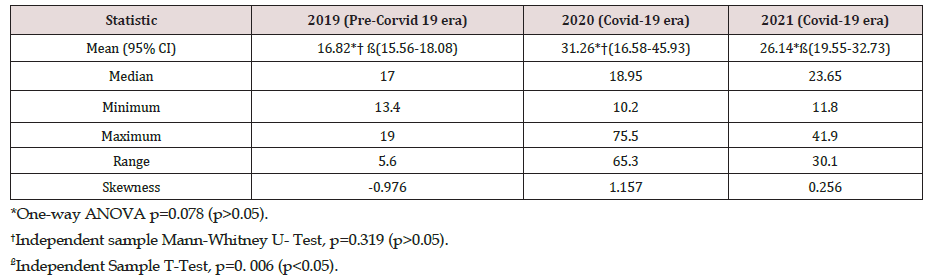

During the pre-Covid-19 baseline year a total of 2911 episodes of prescribing antibiotics for high risk toddlers and children with dento-alveolar infections occurred to a total of 14943 visits. For the Covid-19 stricken 2020 with stringently and partially imposed lock-downs this was 1379 with a total cumulative visits of 8034. Moreover, for the year 2021 which as well demonstrated Covid-19 burden with partially imposed lock downs, a total episode of 1177 antibiotic prescribing happened to a cumulative total visits of 5919. Figure 1 illustrates the monthly % proportion of antibiotic prescribing episodes to high risk toddlers & children presented with dento-alveolar infections to total visits for the years 2019 (pre- Covid 19 era) and Covid-19 milieus in 2020 and 2021. Accordingly, there was an overall marked increase in antibiotic use in the year 2020, especially for the months of April, May and a spectacular increase for the months of November & December 2020, compared to corresponding months in the pre-Covid-19 year 2019. On the other hand, the use of antibiotics was higher in 2021 than in the 2019 especially for the months from May to September 2021. Hence, those surges of antibiotic use corroborated with the peak periods of Covid-19 global pandemic in Sri Lanka. As shown in Table 1, there was a significant increase in % proportion of episodes of prescribing antibiotics for high caries toddlers and children to total episodes of visits to POHU in the year 2021 with Covid-19 milieu compared to pre-Covid-19 year of 2019 (p=0.006). However, this comparison for the year 2020, which marked the emergence Covid-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka did not find a significant difference (p=0.319). Moreover, overall comparisons for pre-Covid- 19 and Covid-19 stricken years of 2021, 2020 and 2021 did not demonstrate significant differences (p=0.078) despite increased episodes of antibiotic prescriptions to total visits in Covid-19 years. Table 2 compares the proportional episodes of prescribing antibiotics for management of dentoalveolar infections among high risk toddlers & children to total number of visits, for the peak Covid-19 periods in 2020 and 2021 with the corresponding periods in pre-Covid-19 era. Accordingly, the mean (95% CI) proportionate antibiotic prescribing was 47.70 (23.83- 71.57) for the peak period of year 2020 whilst it was 16.38 (13.91-18.85) for the corresponding period in 2019. Similarly, the mean (95% CI) proportionate antibiotic prescribing for the peak period of 2021 was 36.30 (29.01-43.58), compared to 17.38 (16.28- 18.47) for the corresponding period in 2019. Those differences were highly statistically significant (p=0.0001 and p=0.007).

Table 1:Comparison of % proportion of episodes of prescribing antibiotics for management of dento-alveolar infections among high risk toddlers & children to total visits for the pre-Covid-19 era (2019) and Covid-19 milieus (2020 & 2021).

Table 2:Comparison of % proportion of episodes of prescribing antibiotics for management of dento-alveolar infections among high risk toddlers & children to total visits for the peak Covid-19 periods in 2020 and 2021 with the corresponding periods of pre- Covid-19- era (2019).

Discussion

Covid-19 global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus remains affecting millions of people, countries, health care systems and economies across the globe since its emergence in December 2019 from Wuhan Province, China [33]. Sri Lanka as a lowermiddle- income developing country with a 21.9 million populations and a per capita GDP of 3682 as per year 2020, [34] became no exception to suffer from the multi-faceted pervasive impact of Covid-19 [35-37]. Sri Lanka employed seven non-pharmaceutical interventions NPIs: contact tracing, quarantine efforts, social distancing and health checks, hand hygiene, wearing of facemasks, lockdown and isolation, and health-related supports to mitigate Covid-19 transmission. However, the second wave that emerged in Sri Lanka in early October 2020 continued despite numerous NPIs [37] until the country resort to mass scale vaccination despite encountering various challenges [38,39]. There is burgeoning literature on the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on health care systems and its use including oral health care from many countries [40-42] that provided useful insights to plan corrective measures to mitigate the negative effect. Furthermore, Covid-19 crisis has increased the burden of AMR with the occurrence of co-infection with bacteria and fungi resistant to antimicrobials whilst causing disruptions to antibiotic stewardship programmed across the globe [43-45]. Antibiotic over-use is a well-known driver for AMR yet became an inevitable outcome of Covid-19 induced health system modifications and health care use, where oral health care became no exception [14-16,18]. However, it is not clear to what extent Covid-19 impacted on use of antibiotics among paediatric dental patients presented with dento-alveolar infections especially in the context of preventive oral health care provision. Against this backdrop, present study provides some novel baseline evidence to bridge this information gap as applied to Sri Lankan context.

However, present findings should be interpreted cautiously as the findings are contextualized to preventive oral health care provision context. Moreover, our data did not include use of analgesics which became mandatory to treat dental pain of children. It is well-known that Covid-19 milieu resulted in overall reductions in dental visits highly skewed towards emergency dental treatment service use both among adults and children for dental emergencies such as pain and swelling due to dento-alveolar infections [46- 49]. In the absence of deferment of aerosol generating treatment procedures, prescribing antibiotics was among the treatment of choice. The salient findings of our research were significantly higher prescribing of antibiotics for high risk toddlers and children presented with dento-alveolar infections during peak periods of Covid-19 with lock-downs in 2020 and 2021 compared to the corresponding periods of the baseline pre- Covid-19 year 2019, Hence, our findings demonstrated an increased incidence of dento-alveolar infections during lock-down periods compared to pre-Covid-19. Our findings were supported by previous work focused on emergency visits of children to POHU in the stringently imposed Covid-19 lock-down period in 2020. That study revealed an overwhelming majority of children presented with toothache, for whom pain relieving and oral hygiene awareness becoming priorities [50]. Moreover, a retrospective study explored oral health care delivery for children during Covid-19 pandemic using the Department of Paediatric Dentistry at Hadassah medical centre, Jerusalem, Israel [16]. This study compared computerized patients records for pre-lock down, lock-down and post lock-down periods. It included 941 mostly healthy 3-6-year-old children [44]. As revealed by the findings, during lockdown most of the children were diagnosed with dento-alveolar abscess (32.3%), compared to 14 and 21% at the previous or subsequent periods, respectively (P < 0.001) [16]. However, treatment provided were different from our study as ours was based on a preventive oral health care setting rather than a paediatric dental clinic. More extractions, pulpectomies and pulp extirpation were the treatments of choice in the lock-down period among paediatric patients in the Israelite study [16] whilst conservative management with antibiotics and analgesics, oral hygiene instructions and dietary advice were the combined treatment that was offered at our setting. Our usual practice was referring the children with dento-alveolar abscesses and symptomatic pulp exposed teeth for pulp therapy provided at Restorative Units of National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka after initial management combined with the preventive oral health care package [51-53]. This comprised behavioural management of the child in the exclusively child friendly environment to gain the cooperation of the child, dietary counselling to address cariogenic dietary habits, oral hygiene and brushing advice, professional fluoride therapy and restorations [51-53]. One restorative unit provided pulp therapy and pulpectomy under general anaesthesia for uncooperative children and other children with special needs who could not be provided with the necessary treatment under general anesthesia. Therefore, attributed to such combined efforts underpinned by the dynamic preventive oral health care model it was possible to dramatically reduce the extractions of symptomatic pulp exposed deciduous/primary teeth of children under general anesthesia over 90% compared to baseline levels without such practices. However, pulp therapy was not provided for children during Covid-19 lock down periods as per circulars issued by the Ministry of Health Sri Lanka stipulating deferment of aerosol generation procedures.

Caries prevention has garnered recognition as the gold standard for orientation of paediatric dentistry professionals which becomes more relevant in emergency situations of pandemics [16]. Nevertheless, prevention and control of premature loss of deciduous teeth due to late sequalae of untreated caries becomes praiseworthy. However, less consideration was given to oral health, despite being an essential and integral component of general health of a child in Covid-19 global pandemic context [54]. As a consequence of lockdowns and deferment of routine dental care, as reported recently in the UK, children and young people including a group of infants who would have been eligible for their first dental visit (365 000, i.e., half of the birth cohort in the previous year), was denied access to routine dental care. Even with resumption of services in June, the capacity to see patients in National Health Service general dental practice was restricted. This was attributed to additional personal protective equipment and fallow time requirements, particularly for all aerosol-generating procedures whilst families remained anxious about returning to perceived ‘high-risk’ environments for non-urgent assessments and treatment [54]. Therefore, providing exclusive preventive oral health care for toddlers and children without restrictions by a developing lower-middle-income country like Sri Lanka seem noteworthy. Lack of statistical significance on proportionate episodes of prescribing antibiotics to overall visits over the pre-Covid-19 and years with Covid-19 milieu could be attributed to overall reductions in visits during lock down scenarios that included emergency visits as well. This finding was supported by other research on emergency dental visits of children [16] as well as adults in Covid-19 lock-downs [24-26]. Moreover, our data did not include toddlers and children who visited the Emergency Treatment Unit (ETU) of National Dental Hospital. Nevertheless, there was high statistical significance on proportionate antibiotic use for total number visits in peak Covid-19 periods in 2020 and 2021 compared to the corresponding periods in the pre-Covid-19 year of 2019. Our previous publication supported significant reduction in utilization of preventive oral health care services in Covid-19 milieu comprising of an aggressive preventive oral health care package with an array of follow up visits [18]. Therefore, transient break down of such services could be directly attributed to occurrence of dento-alveolar infections among children presented with toothache [50]. Moreover, in the absence of such care underpinned by extensive dietary counselling and brushing advice with fluoridated toothpaste it is rational to argue that higher inclination to cariogenic dietary habits by high risk toddlers and children during Covid-19 lock down periods. Therefore, it was important to provide oral health education to children and their parents whilst addressing the acute problems of children [50]. Our usual geographically targeted preventive oral health care package was offered in a child-friendly environment embraced with in-built behavioural management aimed at gaining their cooperation for preventive dental care provision [18,51-53]. As restless, crying children spread more aerosols compared to cooperative children, appropriate and skillful behavioural management techniques have been recommended as a useful strategy to control Sars-Cov-2 infection transmission underpinned by stringent infection control measures [16]. Therefore, prescribing antibiotics for symptomatic dento-alveolar infections helped in gaining their cooperation rather than attempting to provide invasive treatment [16]. Further, our previous research showed the predominantly low socioeconomic background and the cariogenic dietary patterns of toddlers and children attended POHU [51-53,55]. Given the impact of stringently imposed Covid-19 lockdown scenarios on breakdown of normal lifestyles, underpinned by indefinite closure of schools, work-fromhome strategies, impaired health care seeking and breakdown of day-to-day life activities that became pertinent to flatten the rising epidemic curves of Covid-19 infection had its toll of promoting unhealthy lifestyles among adults and children. Consequently, healthy choices did not become easy choices. This notion was supported by a Brazilian study conducted among 1003 parents of children aged ≤13-years that revealed changes in dietary patterns with increase in food intake and the majority willing to take their children only for urgent dental care due to fears of contacting Covid-19 [56]. In contrast, another study conducted among Turkish parents reported reduction in consumption of fast food, packaged food and carbonated beverages by their children whilst supporting the finding of majority of children missing their routine dental appointments due to parental fears of catching Covid-19 [57].

Surveillance of use and consumption of antimicrobials provides useful insights to navigate the policy and practice for their rational use. Data on antimicrobial use collected at the patient level which is thought to be resource-intense provides details on prescribing practices which are vital for managing the antimicrobial stewardship programmed [44]. A recent systematic review on use and misuse of antibiotics in paediatric dentistry revealed a multifactorial relationship leading to increased prescription of antibiotics in pediatric dentistry [58]. However, authors highlighted insufficient evidence in a definitive link in trends of antibiotic prescribing in paediatric dentistry with drug resistance [58]. Moreover, they suggested the importance of introducing interventions on antibiotic stewardship ensuring collaboration between pediatric dentists and patients [58]. Antibiotics have revolutionized health care by preventing and controlling infections, however, since the era of penicillin the use of antibiotics has demonstrated a tremendous rise among medical and dental fraternities [59]. Accordingly, an overuse of antibiotics in dentistry in general and in paediatric dentistry [59- 62] has been reported especially for the treatment of dento-alveolar infections among children [62]. Moreover, the same study revealed the majority of dentists especially those who had a high volume of child patients lacked adherence to professional guidelines for prescribing antibiotics for treatment of dental infections among children [62]. Those findings were further supported by another study conducted among general and paediatric dentists in North Carolina, USA that revealed low adherence to professional guidelines by dentists for prescribing antibiotics for dento-alveolar infections of children [63]. Moreover, similar to an array of other studies [59-62], the commonly prescribed antibiotics in our study were amoxicillin and metronidazole followed by amoxicillin with clavulanic acid. Therefore, routine patient statistics of this nature provides valuable insights in resource constrained settings at institutional sub-unit level.

Protocols on rational use of antibiotics without evidence become unsatisfactory and there is a growing need for translational research on antibiotic consumption which has not become a research priority in many countries especially in developing countries. Further, out of the total health care expenses of around Rs 250 billion incurred by the Ministry of Health Sri Lanka annually, nearly one third is spent on drugs. Antibiotics accounts for a substantially portion (nearly 20%) of the drug bill. For the year 2022, the estimated expenditure is Rs million 121,529 for the Ministry of Health Sri Lanka [64]. Therefore, in a poor resource setting with a very limited fiscal space, managing health expenses is very crucial, especially as the country imports most of its drugs, given the current economic constraints as the country is grappling with foreign currency crisis, management of health expenses becomes even more important. Therefore, rational use of antibiotics in public health care services including oral health care offering services free of charge at the point of service delivery could have made a discernible contribution in this regard. In conclusion, present findings highlight the impact of Covid-19 milieu on increased antibiotic consumption among high risk toddlers and children in preventive oral health care context. Moreover, they support the fact that preventive oral health care model for high risk toddlers and children could not be forsaken despite serious challenges imposed by Covid-19 global pandemic with frequent lock downs and breakdown of routine health care services. Furthermore, rational use of antibiotics in public oral health care services could be a way forward for antibiotic stewardship and for managing the constrained health budget in troubled times.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Dileep de Silva, Department of Community Dental Health, Faculty of Dental Sciences, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka for his overall comments and valuable inputs in Health Economics.

References

- Onyeaka H, Anumudu CK, Al-Sharify ZT, Egele-Godswill E, Mbaegbu P (2021) COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci Prog 104(2): 368504211019854.

- Wang X, Powell CA (2021) How to translate the knowledge of COVID-19 into the prevention of Omicron variants. Clin Transl Med 11(12): e680.

- Ingraham NE, Ingbar DH (2021) The omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: Understanding the known and living with unknowns. Clin Transl Med 11(12): e685.

- Chiu NC, Chi H, Tu YK, Huang YN, Tai YL, et al. (2021) To mix or not to mix? A rapid systematic review of heterologous prime-boost covid-19 vaccination. Expert Rev Vaccines 20(10): 1211-1220.

- Tinanoff N, Baez RJ, Diaz Guillory C, Donly KJ, Feldens CA, et al. (2019) Early childhood caries epidemiology, aetiology, risk assessment, societal burden, management, education, and policy: Global perspective. Int J Paediatr Dent 29(3): 238-248.

- Phantumvanit P, Makino Y, Ogawa H, Rugg-Gunn A, Moynihan P, et al. (2018) WHO Global Consultation on Public Health Intervention against Early Childhood Caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 46(3): 280-287.

- Al-Halabi M, Salami A, Alnuaimi E, Kowash M, Hussein I (2020) Assessment of paediatric dental guidelines and caries management alternatives in the post COVID-19 period. A critical review and clinical recommendations. European archives of paediatric dentistry : official journal of the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry 21(5): 543–556.

- Ilyas N, Sood S, Radia R, Suffern R, Fan K (2021) Paediatric dental pain and infection during the COVID period. Surgeon 19(5): e270-e275.

- American dental association (2020) ADA interim guidance for minimizing risk of COVID-19 transmission.

- Australian dental association (2020) ADA dental service restriction in COVID-19.

- Sales SC, Meyfarth S, Scarparo A (2021) The clinical practice of Pediatric Dentistry post-COVID-19: The current evidence. Pediatric dental journal International journal of Japanese Society of Pediatric Dentistry 31(1): 25–32.

- Schulz-Weidner N, Schlenz MA, Krämer N, Boukhobza S, Bekes K (2021) Impact and Perspectives of Pediatric Dental Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic Regarding Unvaccinated Children: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(22): 12117.

- Cianetti S, Pagano S, Nardone M, Lombardo G (2020) Model for Taking Care of Patients with Early Childhood Caries during the SARS-Cov-2 Pandemic. International journal of environmental research and public health 17(11): 3751.

- Rabie H, Figueiredo R (2021) Provision of dental care by public health dental clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta, Canada. Prim Dent J 10(3): 47-54.

- Marcenes W (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dentistry. Community Dent Health 37(4): 239-241.

- Fux-Noy A, Mattar L, Shmueli A, Halperson E, Ram D, et al. (2021) Oral Health Care Delivery for Children During COVID-19 Pandemic-A Retrospective Study. Front. Public Health 9: 637351.

- Hopcraft M, Farmer G (2021) Impact of COVID-19 on the provision of paediatric dental care: Analysis of the Australian Child Dental Benefits Schedule. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 49(4): 369-376.

- Perera I, Herath C, Perera M, Gajanayake C (2022) Pinch of Prevention in Pounds of Troubles: Utilization of Preventive Oral Health Care Services by High-Risk Children and Other Target Groups Amidst Covid- 19 Milieu. Inter Ped Dent Open Acc J 7(2).

- Koç Y, Akyüz S, Akşit-Bıçak D (2021) Clinical Experience, Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice of Turkish Pediatric Dentists during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina (Kaunas) 57(11): 1140.

- COVID dental Collaboration Group (2021) The COVID-19 pandemic and its global effects on dental practice. An International survey. J Dent 114: 103749.

- Soares RC, da Rosa SV, Moysés ST, Rocha JS, Bettega PVC, et al. (2021) Methods for prevention of early childhood caries: Overview of systematic reviews. Int J Paediatr Dent 31(3): 394-421.

- Ferraz Dos Santos B, Dabbagh B (2020) A 10-year retrospective study of paediatric emergency department visits for dental conditions in Montreal, Canada. Int J Paediatr Dent 30(6): 741-748.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2021) Use of antibiotic therapy for pediatric dental patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill, USA pp. 461-464.

- Rabie H, Figueiredo R (2021) Provision of dental care by public health dental clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta, Canada. Prim Dent J 10(3): 47-54.

- Shah S, Wordley V, Thompson W (2020) How did COVID-19 impact on dental antibiotic prescribing across England? Br Dent J 229(9): 601-604.

- Mian M, Teoh L, Hopcraft M (2021) Trends in Dental Medication Prescribing in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JDR Clin Trans Res 6(2): 145-152.

- Morrison L, Zembower TR (2020) Antimicrobial Resistance. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 30(4): 619-635.

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators (2022) Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399(10325): 629-655.

- Shallcross LJ, Davies DS (2014) Antibiotic overuse: a key driver of antimicrobial resistance. Br J Gen Pract 64(629): 604-605.

- Chiotos K, Tamma PD, Gerber JS (2019) Antibiotic stewardship in the intensive care unit: Challenges and opportunities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 40(6): 693-698.

- Davies J, Davies D (2010) Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74(3): 417-433.

- Perera I, Ratnasekera N, Dissanayake R, Gajanayake C (2018) Contribution of preventive dental treatment options to reduce dental infections among children. The Bulletin of the Sri Lanka College of Microbiologists 16(1): 30.

- To KK, Sridhar S, Chiu KH, Hung DL, Li X, et al. (2021) Lessons learned 1 year after SARS-CoV-2 emergence leading to COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Microbes Infect 10(1): 507-535.

- Annual Report (2020) Central Bank Sri Lanka.

- Wickramaarachchi WPTM, Perera SSN, Jayasinghe S (2020) COVID-19 Epidemic in Sri Lanka: A Mathematical and Computational Modelling Approach to Control. Comput Math Methods Med 2020: 4045064.

- Pathirana Nawodya (2021) COVID-19's Discriminatory Burden on the Sri Lankan Economy Casts a Pall on the Disease.

- Jayaweera M, Dannangoda C, Dilshan D, Dissanayake J, Perera H, et al. (2021) Grappling with COVID-19 by imposing and lifting non-pharmaceutical interventions in Sri Lanka: A modeling perspective. Infect Dis Model 6: 820-831.

- Hayat M, Uzair M, Ali Syed R, Arshad M, Bashir S (2022) Status of COVID-19 vaccination around South Asia. Hum Vaccin Immunother 21: 1-7.

- Wong LP, Alias H, Danaee M, Ahmed J, Lachyan A, et al. (2021) COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine characteristics influencing vaccination acceptance: a global survey of 17 countries. Infect Dis Poverty 10(1): 122.

- Chang AY, Cullen MR, Harrington RA, Barry M (2021) The impact of novel coronavirus COVID-19 on noncommunicable disease patients and health systems: a review. J Intern Med 289(4): 450-462.

- Tonkaboni A, Amirzade-Iranaq MH, Ziaei H, Ather A (2021) Impact of COVID-19 on Dentistry. Adv Exp Med Biol 1318: 623-636.

- Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z (2020) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and Future Challenges for Dental and Oral Medicine. J Dent Res 99(5): 481-487.

- Ukuhor HO (2021) The interrelationships between antimicrobial resistance, COVID-19, past, and future pandemics. J Infect Public Health 14(1): 53-60.

- Dolamulla SS (2021) Reconsidering Middle-Income-Country approaches to a global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) Problem: A Case Study from Sri Lanka. Doctor of Philosophy, University of York, USA.

- Chibabhai V, Duse AG, Perovic O, Richards GA (2020) Collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic: Exacerbation of antimicrobial resistance and disruptions to antimicrobial stewardship programmes? S Afr Med J 110(7): 572-573.

- Wong ES, Hawkins JE, Langness S, Murrell KL, Iris P, et al. (2020) Where are all the patients? Addressing Covid-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care. N Engl J Med.

- Guo H, Zhou Y, Liu X, Tan J (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the utilization of emergency dental services. J Dental Sci 15: 564–567.

- Tobias G, Findler M, Bernstein Y, Meidan Z, Manor L, et al. (2020) Dental emergencies during the COVID-19 no aversion therapy centers. J Dental Sci 5: 000265.

- Moharrami M, Bohlouli B, Amin M (2021) Frequency and pattern of outpatient dental visits during the COVID-19 pandemic at hospital and community clinics. J Am Dent Assoc 30: 0002-8177(21)00584-5.

- Gajanayake C, Perera I, Surendra G (2020) Challenges in emergency oral health care provision in Covid-19 lock-down period. Sri Lanka Journal of Medical Administrators (1): 39-43.

- Perera IR, Wickramaratne PWN, Liyanage NLP, Karunachandra KNN, Bollagala AD, et al. (2013) Preventive dental clinic solutions to tackle early childhood dental caries. International Conference on Public Health Innovations. National Institute of Health Sciences Sri Lanka.

- Karunachandra KNN, Bollagala AD, Perera IR, Liyanage NLP, Kottahachchi MJ, et al. (2013) Behavioural management strategies and oral health related behaviours of preschool children receiving preventive dental care. International Conference on Public Health Innovations. National Institute of Health Sciences Sri Lanka.

- Perera I, Herath C, Perera M, Dolamulla S, Jayasundara Bandara JM (2017) Service Delivery of a Preventive Oral Health Care Model to High Caries Risk Urban Children in Sri Lanka: A Retrospective, Descriptive Study. Journal of Advances in Medicine and Medical Research 20(3): 1-10.

- Okike I, Reid A, Woonsam K, Dickenson A (2021) COVID-19 and the impact on child dental services in the UK. BMJ Paediatr Open 5(1): e000853.

- Surendra G, Perera I, Perera M, Herath C, Attanayake S (2021) Presentation of Untreated Dental Caries for Preventive Oral Health Care and Socio-Behavioural Attributes of Toddlers Attended a Public Dental Hospital in Sri Lanka. Inter Ped Dent Open Acc J 6(3).

- Campagnaro R, Collet GO, Andrade MP, Salles JPDSL, Calvo Fracasso ML, et al. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and pediatric dentistry: Fear, eating habits and parent's oral health perceptions. Child Youth Serv Rev 118: 105469.

- Kalyoncu IÖ, Özcan G, Kargül B (2021) Oral health practice and health-related quality of life of a group of children during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Istanbul. J Educ Health Promot 10: 313.

- Aidasani B, Solanki M, Khetarpal S, Ravi Pratap S (2019) Antibiotics: their use and misuse in paediatric dentistry. A systematic review. Eur J Paediatr Dent 20(2): 133-138.

- Al-Johani K, Reddy SG, Al Mushayt AS, El-Housseiny A (2017) Pattern of prescription of antibiotics among dental practitioners in Jeddah, KSA: A cross-sectional survey. Niger J Clin Pract 20(7): 804-810.

- Konde S, Jairam LS, Peethambar P, Noojady SR, Kumar NC (2016) Antibiotic overusage and resistance: A cross-sectional survey among pediatric dentists. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 34(2): 145-151.

- Aly MM, Elchaghaby MA (2021) The prescription pattern and awareness about antibiotic prophylaxis and resistance among a group of Egyptian pediatric and general dentists: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health 21(1): 322.

- Ahsan S, Hydrie MZI, Hyder Naqvi SMZ, Shaikh MA, Shah MZ, et al. (2020) Antibiotic prescription patterns for treating dental infections in children among general and pediatric dentists in teaching institutions of Karachi, Pakistan. PLoS One 15(7): e0235671.

- Cherry WR, Lee JY, Shugars DA, White RP Jr, Vann WF Jr (2012) Antibiotic use for treating dental infections in children: a survey of dentists' prescribing practices. J Am Dent Assoc 143(1): 31-38.

- Budget estimates (2022) Fiscal year2022 Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...