Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Emergency Oral Health Care Provision for Late Squeal of Early Childhood Dental Caries in Covid-19 Lockdown Scenario Volume 5 - Issue 2

Gayan Surendra1 and Irosha Perera2*

- 1Office of Deputy Director General Dental Services, Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka

- 2Department of Preventive Oral Health Unit, National Dental Hospital Teaching, Sri Lanka

Received:December 17, 2020; Published: January 05, 2021

*Corresponding author: Irosha Perera, Department of Preventive Oral Health Unit, National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka, Ward Place, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2021.05.000210

Abstract

COVID-19 denotes a multifaceted global public health challenge that persists to impact health systems, economies, and societies across the globe almost over a period 12 months. Consequently, oral health care services have transformed to minimize the risk of COVID-19 infection transmission by adherence to patient triaging, risk stratification and meticulous infection control. Stringently imposed country-wise locks down scenarios were common in the first wave of COVID-19 that lasted early part of this year. Early childhood dental caries (ECC) as the most common chronic childhood disease affect toddlers and young children often resulting emergency paediatric dental visits due to its late sequel such as pain, swelling and infection. Against this backdrop, this short report investigates provision of emergency oral health care for children presented with late sequel of ECC to a premier tertiary public dental hospital in Sri Lanka during stringently imposed lock down.

Abbreviations: ECC: Early Childhood dental Caries; PPE: Personal Protective Equipment

Background

COVID-19 denotes an unprecedented persistent global public health challenge transforming health care delivery towards triaging and redefining of treatment priorities [1]. Providing emergency health care for patients while streamlining resources for managing COVID-19 epidemic has become the overarching goal of health administrators. Sri Lanka is a lower-middle-incomedeveloping country, possessing an efficiently pro-poor public health care delivery model [2]. Oral health care services are closely being integrated into the existing public health care delivery model from outpatient dental care to specialized care [3]. Oral health is fundamental to performing vital daily functions such as eating, speaking, and sleeping. A community’s opportunity to access to dental care, therefore, is considered to be a fundamental human right [4]. Early childhood dental caries (ECC) denotes one of the most common chronic childhood diseases [5] often goes untreated giving rise to late sequalae such as symptomatic pulp exposed teeth and frequent dento-alveolar infections. Consequently, such conditions give rise to emergency visits of children having dental pain and swelling [6]. Less optimal oral hygiene practices, cariogenic dietary patterns and lack of availability and accessibility to preventive oral health care services are the major determinants of dento-alveolar infections among children [7]. Untreated childhood dental caries, hence, constitutes one of the common unmet health needs in children especially from socially disadvantaged and culturally diverse backgrounds [8]. Preventive oral health package tailored to such children could make them “low risk” thereby preventing and controlling frequent emergency dental visits. This model has catered to high caries risk urban children in the Colombo Municipal Council area [9,10] identified as one of the high-risk zones for COVID-19 epidemic in the Colombo district. National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka is the premier multi-specialty tertiary care public dental hospital in the country. In this backdrop, present report explores some aspects of emergency management services offered by this hospital for children presented with pain, swelling and infection due to ECC in the peak of lockdown period and the challenges encountered.

Methodology

The data were extracted from performance statistics of Preventive Oral Health Unit (POHU), National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka, from 6th April 2020 to 5th May 2020 for a random sample of visits. Data were entered and analysed using SPSS-21 statistical software package.

Results

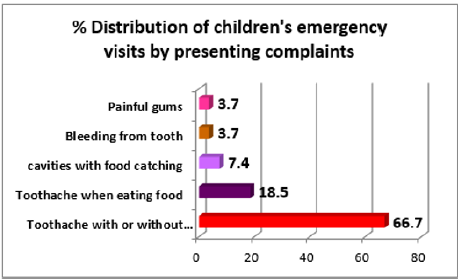

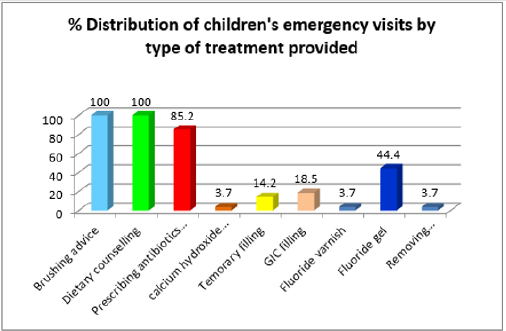

Figures 1 & 2 show presenting complaints and types of emergency management services provided respectively for 27 visits of children with ages ranging from 2 to 7-years. Accordingly, the majority, 66.7% of children’s visits were due to tooth ache with or without facial swelling. Consequently, 85.2% visits needed prescribing antibiotics and analgesics combined with other necessary treatment procedures. Dietary counseling and brushing advice were provided for 100% of visits.

Discussion

Children who made emergency visits for dento-alveolar infections were attended by dental surgeons who adhered to protocols of cross-infection control fully equipped with personal protective equipment (PPE). All parental care givers and children were triaged with history taking and temperature checks at the main entrance conducted by Nursing Officers supported by Health Assistants. This procedure was repeated at the waiting area of POHU. While prescribing antibiotics and analgesics, dietary and brushing advices highlighting the need for fluoride toothpaste use, night brushing and healthy dietary pattern were emphasized. Moreover, fluoride gel and varnish applications, simple fillings and fissure sealant applications were performed for selected children while addressing their painful teeth to augment further prevention of emergency dental visits due to acute exacerbations of dentoalveolar infections. This fostered stay-home-stay-safe strategy fundamental to containment of spread of COVID-19 [11,12]. Those complied with the international guidelines on paediatric dentistry that emphasized triaging and exclusive treatment for emergency cases by minimizing aerosol generation procedures underpinned by case-base selection of biological, non-invasive, or minimally invasive treatment methods [13]. Few children had repeated doses of antibiotic and analgesics as there were relapses of pain and residual infections which got aggravated at night resulted in making late night emergency visits to the emergency treatment unit. Other children developed toothache while eating food that needed special oral hygiene advice and management. Break down of routine preventive oral health care provision that comprised of regular follow-up visits could have substantially impacted on the oral health status of those children. This could have been mediated by cariogenic dietary patterns and less optimal brushing habits common among children who belong to families of low socioeconomic backgrounds [14]. A recent study conducted in Brazil reported those changes in dietary habits of children as perceived by parents and their fears in accessing dental care for the children except for urgent visits [15]. Therefore, such factors could have contributed for patterns of utilization of preventive oral health services observed in this study during COVID-19 waves. However, the absence of provision of routine services on comprehensive management of advanced childhood dental caries such as pulp therapy appeared problematic. Consequently, managing dental pain of some children became challenging. Furthermore, prevailed transport problems and allocation of health assistants for priority services at Infectious Disease Hospital and other hospitals with COVID-19 care provision resulted in unavailability of supportive staff at times.

Conclusion

Relieving dental pain and consequences of advanced early childhood dental caries by providing emergency management services during COVID-19 lock down scenario was a formidable challenge. However, the services provided for the children were helpful in controlling dento-alveolar infections whilst restoring their oral health status. With antibiotics and analgesics, the majority of children presented with dental pain and multiple dental caries received professional fluoride applications. The need for re-commencement of routine preventive and conservative dental treatment for high caries children with strict adherence to optimal safety measures seems an emerging need.

References

- Schrag D, Hershman DL, Basch E (2020) Oncology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 323(20): 2005-2006.

- Smith O (2018) Sri Lanka: Achieving Pro-Poor Universal Health Coverage without Health Financing Reforms. Universal Health Coverage Study Series No. 38, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, USA.

- (2018) National Oral Health Survey Sri Lanka 2015-2016. Colombo: Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine, Sri Lanka.

- Perera I, Kruger E, Tennat M (2012) GIS as a decision support tool in health informatics: spatial analysis of public dental care services in Sri Lanka. Journal of Health Informatics in Developing Countries 6(1): 422-433.

- American Academy of Pediatric dentistry Definition. (2008) Definition of Early Childhood Caries (ECC). American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry 4(3): 15.

- Azodo CC, Chukwumah NM, Ezeja EB (2012) Dento-alveolar abscess among children attending a dental clinic in Neigeria. Odonto-stomatologie tropicale 35(139): 41-46.

- (2019) Ending childhood dental caries: WHO implementation manual. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence CC BY-NC-SA 3.0IGO.

- Isong I, Dantas L, Gerard M, Kuhlthau K (2014) Oral Health Disparities and Unmet Dental Needs among Preschool Children in Chelsea, MA: Exploring Mechanisms, Defining Solutions. J Oral Hyg Health 2: 1000138.

- Perera IR Wickramaratne PWN, Liyanage NLP, Karunachandra KNN, Bollagala AD, Kottahachchi MJ, et al. (2013) Preventive dental clinic solutions to tackle early childhood dental caries. National Institute of Health Sciences, Kalutara. International Conference on public health innovations. Conference Programme and abstract book, p. 55.

- Perera IR, Herath CK, Perera ML, Dolamulla SS, Jayasundara Bandara JMW (2017) Service delivery of a preventive oral health care model to high caries risk urban children in Sri Lanka: a retrospective descriptive study. British Journal of Medicine & Medical Research 20(3): 1-10.

- Ratnasekera N, Perera I, Kandapolaarachchige P, Surendra G, Dantanarayana A (2020) Supportive care for oral cancer survivors in COVID-19 lockdown. Psychooncology 29(9): 1409-1411.

- Jayasuriya NSS, Perera IR, Ratnapreya S (2020) Maxillofacial Surgery and COVID-19, the Pandemic! J Maxillofac Oral Surg 19: 475–476.

- Al-Halabi M, Salami A, Alnuaimi E, Kowash M, Hussein I (2020) Assessment of paediatric dental guidelines and caries management alternatives in the post COVID-19 period. A critical review and clinical recommendations. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 21(5): 543-556.

- Karunachandra KNN, Bollagala AD, Perera IR, Liyanage NLP, Kottahachchi MJ, et al. (2013) Behavioural management strategies and oral health related behaviours of preschool children receiving preventive dental care. International Conference on Public Health Innovations. National Institute of Health Sciences Sri Lanka.

- Campagnaro R, Collet GO, Andrade MP, Salles JPDSL, Calvo Fracasso ML, et al. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and pediatric dentistry: Fear, eating habits and parent's oral health perceptions. Child Youth Serv Rev 118: 105469.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...