Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Effectiveness of a School Oral Health Education Program in Yangon, Myanmar Volume 4 - Issue 1

Zar Chi Kyaw Myint1,2, Takashi Zaitsu1*, Akiko Oshiro1, Ko Ko Soe2 and Yoko Kawaguchi1

- 1Department of Oral Health Promotion, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan

- 2Department of Preventive and Community Dentistry, University of Dental Medicine (Yangon), Yangon, Myanmar

Received: April 14, 2020; Published: June 05, 2020

*Corresponding author: Takashi Zaitsu, Assistant Professor, Department of Oral Health Promotion, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Japan

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2020.04.000180

Abstract

Aim: We evaluated the effectiveness of oral health education in terms of oral health literacy, knowledge, behaviors, and oral health status among middle school students in Yangon, Myanmar.

Materials and Methodss: This 1-year study enrolled 10- to 11-year-old students. At baseline, a dentist provided health education to group A (n=247), and peer group leaders reinforced it. Group B (n=195) received no education program. After 6 months, the dentist provided education to both groups, and classroom teachers reinforced it. Both groups received questionnaire surveys and oral examinations at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

Results: There were no between-group differences at baseline. After 6 months, group A showed significant improvements in oral health literacy, knowledge, and behavior as well as reduction in dental plaque, gingivitis, and plaque bacterial levels. Group B only showed improved brushing and mouth rinsing behaviors. After 1 year, all items were significantly improved in both groups, although sweet snack/drink consumption behaviors remained unchanged and dental caries increased. At 1 year, group differences were not significant.

Conclusion: Oral health education is effective in improving oral hygiene, decreasing gingivitis, and reducing plaque bacteria levels by improving oral health literacy, knowledge, and behaviors. However, eating behaviors and dental caries were difficult to change within 1 year

Keywords:School oral health; Oral health education; Middle school

Abbreviations: HPS: Health-Promoting School; OHLI: Oral Health Literacy Instrument; CMOHK: Comprehensive Measurement of Oral Health Knowledge; OHBs: Oral Health Behaviors; DT: Decayed Teeth; FT: Filled Teeth;

Introduction

Dental caries and periodontal diseases are the most common oral health burdens in industrialized countries and in developing countries [1,2]. In some developing countries, dental caries affect a substantial proportion of children and are a public health problem [3,4]. Dental caries are increased among school children in developing countries where limited oral health services [1] and school-based oral care programs are not established [5,6]. Compared to children without poor oral health, children with poor oral health are 12 times more likely to have restricted activity days when missing school [7]. More than 50 million school hours are lost annually because of oral diseases [8]. A health-promoting school (HPS) constantly aims to strengthen its capacity to promote healthy living, learning, and working condition [9]. An HPS has the following key features: [10]

a) Healthy school policies,

b) A physical school environment,

c) A social school environment,

d) Health skills and education,

e) Links with parents and the community, and

f) Access to school health services.

An effective school health program uses cost-effective investments, and each country can improve education and health simultaneously through a health program [11]. Much evidence indicates that an oral health promotion program in school is needed and that it can easily be incorporated into general health promotion, school curricula, and activities [8].

Schools provide an ideal setting for oral health promotion and are one of the best places to give oral health information to children to achieve the goals of a health education program [2,8]. Oral health education messages can be reinforced regularly throughout the school years. A single session of health education cannot achieve the set goals, particularly among young children, and health education programs with reinforcement have shown some effectiveness [12,13]. In schools, peers may strongly influence other students’ behaviors and share experiences and feelings, and peers represent an important role in an adolescent’s socialization process [14]. Teachers have a positive influence on society and are guides and role models for students [11]. Trained teachers and peers can have a key role in the reinforcement and enhancement of the success of school-based oral health education programs [13]. Low oral health literacy is associated with poor oral health knowledge, oral behaviors, and oral health status [15]. School-based oral health education interventions can have positive impacts on improving oral health literacy to develop behavioral outcomes and clinical oral health status among students [16,17].The basic education system in Myanmar consists of primary education (kindergarten to grade 4), lower secondary education (middle grade years 5–8), and upper secondary education (high grade years 9–10). The basic education curriculum is taught from age 5 to 16 years in Myanmar. Secondary schools are usually combined and contain middle and high schools [18]. In Myanmar, 6224 lower secondary (i.e., middle) schools exist and contain 129,945 teachers with approximately 2.79 million students [18].

In 2015, 4539 dentists practiced in Myanmar and the dentist per population ratio was 1:16,000 [19]. A wide gap exists between dental healthcare services and the dental health condition of the population. Not all citizens in Myanmar are covered by health insurance [20]. A comprehensive evaluation and research helps to strengthen a school’s health program and determine the current outcomes of ongoing activities and the program’s cost-effectiveness or benefits [8,21]. In Myanmar, very limited data are available regarding the impact of health education on the clinical oral health status of students [22]. Moreover, the lack of annual school oral health data is a problem when planning a school-based oral health program. Therefore, implementing a cost-effective school-based oral health promotion program is necessary in a country where the number of dental professionals are limited. A previous study [23] in Myanmar reported that students with a mixed dentition had a high prevalence of dental caries and gingivitis, as well as poor oral hygiene and inadequate oral health care habits. Therefore, the present study was targeted at middle school students and aimed to evaluate the effects of oral health education on oral health literacy, knowledge, and behaviors and oral health status among this student population in Myanmar.

Materials and Methods

Sampling methods and sample size

This 1-year follow-up study was conducted in Yangon, Myanmar from December 2017 to December 2018. Two townships with a similar sociodemographic status in Yangon region were selected. Two public schools in each township were randomly chosen; in total, four schools participated in this study. All were middle schools with the same academic performance level, curriculum, and school environment, and none of the schools had organized an oral health education program. In each township, one school constituted group A and the second school constituted group B. After obtaining consent from the school authorities, a written informed consent form was sent to the students and their guardians. The exclusion criteria in this study were students who had systemic diseases or neuromuscular dysfunction, students with fixed orthodontic treatment, and students without their parents’ agreement to participate. The required sample size for this study was 362 students (181 per group), based on a power test of 0.80 and compensating for a 10% loss of response rate. A previous study by Ueno et al. [24], which was also part of a school oral health promotion program, was used as the parameter for sample size calculation.

Study procedure

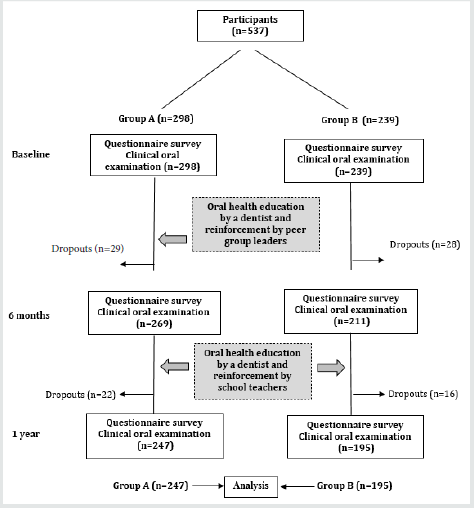

Because the school authorities wanted all students to receive the same benefit, we invited all grade 5 students in the four schools to participate. Therefore, the number of students in each group exceeded the upper limit of the estimated sample size. From 569 eligible students, 32 students were excluded and 537 students (group A: 298 students; group B: 239 students) completed the questionnaire surveys and clinical oral examinations at baseline. Among these, 442 students (group A: 125 boys and 122 girls; group B: 87 boys and 108 girls) completed the 1-year follow-up examination; thus, the follow-up rate was 82.3% (Figure 1). The dropout rate was 18%. The common reasons for dropout included transfer to another school or absence on the examination day. The questionnaire survey and oral examinations were conducted at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year. The study design was a comparative study of two groups; one group received health education at the baseline and at 6 months while the second group received health education only at 6 months. This study received ethical approval from the ethics committees of the Department of Medical Research in Myanmar (No. Ethics/DMR/2017/064), University of Dental Medicine (Yangon), and Tokyo Medical and Dental University (no. D2017-018). The study was conducted in full accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association. Information regarding approval can be provided on request.

Questionnaire survey

To evaluate the students’ skill in reading and understanding information about oral health and to evaluate their knowledge about oral health, 10 items from the reading comprehension section of the Oral Health Literacy Instrument (OHLI) [15] and nine questions from the Comprehensive Measurement of Oral Health Knowledge (CMOHK) questionnaire [25] were used. In the modified OHLI and CMOHK, a “correct” answer was scored with 1 point and an “incorrect,” “do not know,” or “not answered” response was scored with 0 points. Thus, the modified oral health literacy score ranged from 0 to 10 points, and the modified CMOHK score ranged from 0 to 9 points. The original English versions of these questionnaires were translated into the Burmese language and then back-translated. Expert panels confirmed the content and consistency. In a pilot study, the translated Burmese versions were tested among 25% of the participants. Based on the feedback, minor corrections were made so that the questionnaire would be suitable for students. Test–retest reliability was conducted 2 weeks later for reliability testing. The interclass correlation coefficient for oral health literacy and CMOHK were 0.78 and 0.82, respectively. Internal consistency, assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.70 and 0.73 for the OHLI and CMOHK, respectively. Questions regarding oral health behaviors asked the students about daily tooth-brushing frequency (“less than once a day,” “once a day,” “twice a day,” and “more than twice a day”), daily mouth-rinsing habit (“ once a day,” “twice a day,” “three time a day,” and “never”), having a dental visit within 6 months, and daily consumption of sweet snacks and/or drinks from snack shops at schools and near their home (“yes” or “no”). The validity of these questionnaires was reported in a previous paper [23].

Clinical oral examination

One dentist conducted the oral examinations of the students by using a dental mirror and a community periodontal index probe under an artificial light. In the oral examination, the dentist assessed the students’ dental caries status (using the decayed, missing, filled teeth [DMFT] index), based on the World Health Organization guidelines [26]; oral hygiene status, based on the debris index (i.e., DI-S) [27]; and the gingival status of 12 anterior teeth, based on the papillary, marginal, attached gingiva (PMA) index [23,28]. Intra examiner agreement value was defined as “excellent” for dental caries (0.90) and as “good” for DI-S (0.76), PMA (0.77). After the clinical examination, the dentist advised the students in both groups to receive dental treatment, if necessary.

Bacterial tests

A bacteria counter machine (Panasonic, Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure the bacteria in dental plaque from the buccal surface of the cervical portion of the upper left permanent first molar [23]. After the clinical examination, the same investigator conducted the bacterial tests.

Oral health education

At baseline, the dentist provided health education to group A and specially trained peer group leaders. From baseline to 6 months, the peers repeated the dentist’s information by using posters to their classmates in a small group. This activity required only 5–10 minutes per week. By contrast, group B students did not receive education program. After 6 months, the dentist provided both groups health education. From 6 months to 1 year, specially trained classroom teachers reinforced the health education with the students by using posters. They reinforced it once weekly for 5–10 minutes. The dentist used visual modes (e.g., slide projector, photo albums, posters, dental models) for education, followed by self-checkup training by using a hand mirror and dental mirror to improve the students’ self-evaluation of their oral health status. These mirrors were then given to students who received education so they could continue daily checkups at home. The 30-minute health education focused on healthy teeth and gingiva, signs and symptoms of dental caries and gingivitis, treatment, and the prevention of dental diseases. The health education messages were written on posters and displayed on a wall in their classrooms. The topics, instructions, and training program presented the same content to both groups. Burmese language was used for delivering health education. Toothbrush and toothpaste were provided to all participants after the clinical examination.

Statistical analysis

The questions regarding oral health behaviors were categorized under the following domains: tooth-brushing frequency (≤1 time daily [0] or ≥2 times daily [1]); mouth-rinsing behavior (“never” [0] or “ ≥ once a day” [1]); dental visit within 6 months (“no” [0] or “yes” [1]); and daily sweet snack/drink consumption (“no” [0] or “yes” [1]). The clinical outcome of the bacterial test results was categorized as level 1–4 (i.e., “low”; 0) or level 5–7 (i.e., “high”; 1). The association of categorical variables was analyzed by using the Chi-square test and McNemar’s test. Mean differences in continuous values for the within group comparisons were analyzed by using paired t-tests from baseline to 6 months (i.e., the first 6 months) and from 6 months to 1 year (i.e., the second 6 months). The betweengroup comparisons were analyzed at baseline, at 6 months, and at 1 year by using the Student t-test. Statistical Program of Social Science (SPSS, version 21; IBM, Tokyo, Japan) was used for data analysis. The significance level for all results was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Oral health literacy and knowledge

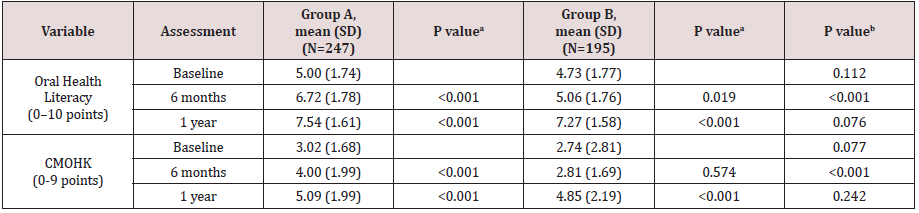

At baseline, no significant difference existed between the two groups for any item. Table 1 shows the Oral health literacy and CMOHK scores of the students at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year. The mean literacy score significantly increased in both groups from baseline to 6 months and from 6 months to 1 year. With regard to the CMOHK, a significant improvement occurred in group A in the first 6 months and in the second 6 months. However, in group B the mean CMOHK score increased significantly only in the second 6 months. In the comparison between the two groups, oral health literacy and CMOHK scores were significantly improved in group A than in group B at 6 months. However, no significant differences existed between the two groups at 1 year.

Table 1: Comparison of the Oral Health Literacy and CMOHK scores in Groups A and B at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

aThe P value is based on the intragroup comparison between baseline and 6 months and between 6 months and 1 year. bThe P value is based on the intergroup comparison at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

Oral health behaviors

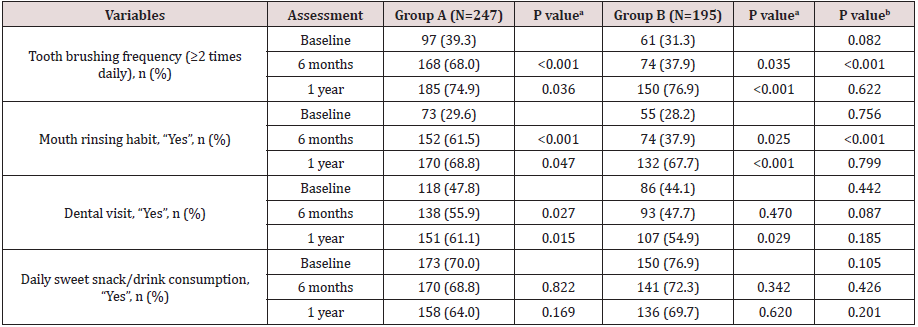

The comparisons of the percentage of students’ oral health behaviors (OHBs) are in Table 2. Students in both groups reported a significant increase in tooth-brushing frequency (≥2 times per day) and in adopting a daily mouth-rinsing habit from baseline to 6 months and from 6 months to 1 year. Dental visit experience was significantly increased in group A for both 6-month periods, whereas it was significantly improved in group B for only the second 6-month period. However, daily sweet snack/drink consumption behaviors did not significantly change after 6 months or at 1 year in either group. In addition, at 6 months, OHBs significantly improved in group A, compared to group B, except for dental visit experience and dietary habit. After 1 year, no significant difference existed between the two groups in OHBs.

Table 2: Comparison of oral hygiene behaviors at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

aThe P value is based on the intragroup comparison between baseline and 6 months and between 6 months and 1 year. bThe P value is based on the intergroup comparison at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

Oral health status

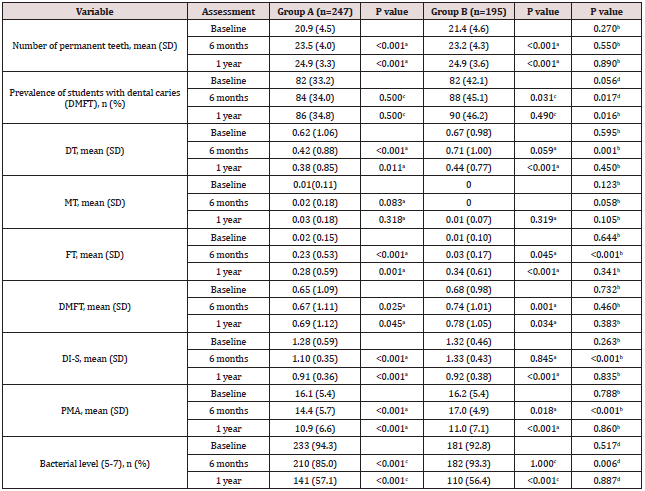

Table 3 shows the oral health status of the students at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

Number of permanent teeth: The number of permanent teeth in both groups significantly increased until 1 year. This parameter was not significantly different between the two groups at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

Dental caries: The percentage of students with dental caries in the permanent teeth (DMFT index) was significantly increased in group B from baseline to 6 months; however, no significant changes occurred in group A in the first 6 months and in the second 6 months. At 6 months and at 1 year, group B had a significantly higher percentage of students with DMFT than did group A. The number of untreated decayed teeth (DT) was significantly reduced in group A in both 6-month periods. By contrast, the number of untreated DT was significantly reduced in group B in the latter 6 months. A comparison between the two groups at 6 months revealed a significant reduction in group A. No significant changes occurred in the mean number of missing teeth within each group or in the between-group comparison within 1 year. A significant increase in filled teeth (FT) was detected in both groups in the first 6 months and in the second 6 months. At 6 months, group A had a significantly higher number of FT than did group B. After 1 year, no significant differences were detected between the two groups. Dental caries (DMFT index) was increased in both groups from baseline to 6 months and from 6 months to 1 year. No difference in the DMFT values existed between the groups at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

Oral hygiene condition: The mean DI-S was significantly reduced in group A in the first 6-month and second 6-month periods. However, in group B, the DI-S did not show a significant reduction until 1 year. At 6 months, the mean DI-S score was significantly reduced in group A, compared to group B. The intergroup comparison of the mean DI-S revealed no significant changes at 1 year. Gingival condition. In group A, gingivitis (PMA index) was significantly reduced in the first 6-month and second 6-month periods. However, gingivitis in group B significantly worsened from baseline to the 6-month follow up. A significant reduction in gingivitis only occurred in group B from 6 months to 1 year. Gingivitis was significantly different between the two groups only at 6 months.

Oral bacteria level: In the intragroup comparison, the percentage of group A students with a high level of bacteria (i.e., level 5–7) significantly decreased from baseline to 6 months and from 6 months to 1 year. However, the percentage of group B students with a high bacteria level (i.e., level 5–7) significantly reduced from 6 months to 1 year. The reduction in the bacterial level was significantly different between group A and group B only at 6 months.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effectiveness of oral health education on oral health literacy, knowledge, behaviors, and oral health status among middle school students in Yangon, Myanmar. Our findings indicated that an oral health education program had significant positive effects on the oral health of middle school students in Myanmar, and it may be an economically cost-effective education method. Group A students had a significant improvement in oral health literacy, knowledge, behaviors, increased number of FT, and reduction in plaque, gingivitis, and plaque bacteria levels from baseline to 6 months. This outcome may be completely attributed to the impact of health education with self-checkup training by the dentist. Daily self-checkup training could help children observe and judge their oral health condition correctly. Moreover, peer group leaders could lead their peers and effectively deliver information. Several studies [6,29-31] report that health education with a peer group approach effectively improved the oral health related knowledge, behaviors and oral hygiene status of students.

Table 3: Comparison of the oral health status at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

aThe value is based on the intragroup comparison between baseline and 6 months and between 6 months and 1 year.

bThe value is based on the intergroup comparison at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

cThe value is based on the intragroup comparison between baseline and 6 months and between 6 months and 1 year.

dThe value is based on the intergroup comparison at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year.

However, group B students also had significant improvements

in oral health literacy, tooth-brushing and mouth-rinsing habits, and

FT during the first 6 months. This finding indicated that, even in the

absence of health education, the impact of school dental checkups

improved oral health related knowledge, behaviors, and number

of filled teeth among the group B students. Dental screening in the

school setting, followed by informing their guardians about the oral

condition of their child as detailed recommended to received dental

treatment improved the children’s oral health [32]. Moreover, some

children may have tried to search and obtain correct answers and

gain knowledge about oral health through various sources.

In this study, a control group without health education was

not used because of ethical reasons. All students have the right to

receive the benefits of health education; therefore, we divided the

students into two groups—the early intervention group (group A)

and the late intervention group (group B)—and compared their

results.

During the second 6 months, significant improvements

occurred in both groups in oral health literacy, knowledge, and

behaviors (except sweet snack/drink consumption) with a

reduction in plaque accumulation, gingivitis, and plaque bacterial

level. No significant differences occurred between the two groups

at the 1-year examination. This finding may be because, compared

to group A, the students in group B surprisingly improved their

knowledge, behaviors, and clinical oral health status from 6

months to 1 year. These results suggested that health education by

a dentist could be effectively augmented and reinforced by school

teachers. Previous papers [33-35] also report the same outcomes

as in this study and indicate that reinforcement of health education

addressed to students by school teachers helped the students to

improve their knowledge, their behaviors related to oral health, and

their oral hygiene status (based on the DI-S). Another reason for

this finding is that the students in group B had previous exposure

to an oral examination by the same dentist and they were therefore

willing to follow the dentist’s instructions.

A previous paper [23] suggested that a bacterial count using

a bacteria counter machine requires only 1 minute to obtain and

the device is easy to use. Moreover, students or children can easily

recognize their oral hygiene status by checking the face icon.

In addition, the machine can be used as a motivating factor for

students. Education messages and instructions were the same in

the first 6 months and the second 6 months in group A. Therefore,

the progress in group A in the second 6 months was not substantial,

compared to the progress in the first 6 months. However, they

maintained good oral health knowledge, behaviors, and oral health

status until the 1-year follow up.

The findings of this 1-year study were in contrast with those

of a previous study [36], which reported that students who

received health education earlier had better improvements in

tooth-brushing behaviors and the bacteria plaque score than did

students who received an education program later. However, the

reinforcement used in the aforementioned study was different

from the reinforcement used in the current study. The DMFT was

significantly increased in both groups within 1 year. Several studies

[37-40] have been conducted in Bangladesh, Tanzania, Greece, and

Indonesia to evaluate the impact of health education on dental

caries. The investigators in these studies had a similar conclusion

as that of this study. In the current study, the dental caries status

was recorded by using the DMFT index, which thus permitted the

recording of carious cavities.

One year may be a short period for detecting changes in caries.

A significant number of students visiting the dental clinic might

have had a positive effect on the increased number of FT after the

education program. A previous study [37] conducted in Bangladesh

also reported that an education program significantly reduced

untreated dental caries among adolescents. The comparison of the two groups revealed that students who received dental screening

with oral health education had a significant increase in the number

of dental visits and FT and reduction in untreated dental caries.

This study’s findings indicated that school oral health education

programs are a potential solution for the shortage of dentists and for

poor oral health behaviors and poor oral health status of students

such as those in Myanmar. Investigators in a previous 2-year study

in Pakistan [6] concluded that dentist-led, teacher-led, and peer-led

strategies of education methods are equally effective for improving

oral health knowledge and oral hygiene status among students.

In the current study, sweet snack/drink consumption behaviors

did not change in either group during the 1-year period. Some

previous studies [6, 35,40] demonstrated a significant reduction

in sweet snacks consumption behavior after implementing health

education, which contrasts with the findings of the present study.

In Myanmar, every school has a school canteen and most snacks

and drinks available for students are sweet and unhealthy foods.

The temptation to ingest sugary foods and drinks is difficult for

students to refuse during their snack time at schools. To change this

dietary habit, school officials need to modify unhealthy snacks to

healthy snacks in school snack shops. Moreover, the tooth-brushing

environment is unsatisfactory in schools, and environmental

changes are definitely needed in schools. School oral health

promotion programs in Myanmar require effective cooperation

between school authorities, teachers, peer groups, families,

professionals, and support from the government to improve the

oral health status of students.

One limitation of the present study was that the four selected

schools were not representative of the whole Myanmar population.

Moreover, the duration was only 1 year. Further long-term studies

with larger samples should be conducted for the generalization

of the results. Another limitation is that some questions used

categorical responses to record sugar consumption practices at the

school snack shops. In addition, oral hygiene behavior outcomes

were based on information derived from self-reported surveys (i.e.,

information and response bias exist). The improvement in the oral

health status of the participants, as well as a decrease in the risk

indicators of dental caries and gingivitis [23], indicated that the

students well improved their oral health literacy and knowledge,

and they adopted good oral hygiene behaviors long after the

education programs. We believe that these favorable outcomes

of a school oral health education program could be a good model

for expanding health-promoting schools in Myanmar and in other

developing countries.

Conclusion

Oral health education in schools improved the students’ oral health knowledge, oral hygiene behavior, and clinical oral health status of Myanmar middle school students. The impact of peer and school teachers as health educators is an economical cost-effective method and could be used as a model for future school oral health education programs in Myanmar.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the school authorities and students who participated in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Petersen PE (2005) Priorities for research for oral health in the 21st Century-the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Health 22(2): 71-74.

- Kwan S, Petersen PE (2003) Oral health promotion: an essential element of a health-promoting school. WHO Information Series on School Health, Document Eleven, Geneva.

- Bali Declaration-Good Oral Health as Investment in Children’s Future (2013) The 7th Asian Conference of Oral Health Promotion for School Children (ACOHPSC) held on September 12–14, 2013 in Bali, Indonesia. Geneva, Switzerland: FDI World Dental Federation.

- Bansal R, Sharma S, Shukla AK, Parashar P, Singh D, et al. (2015) Prevalence of dental caries among school children in Meerut. Asian Pac J Health Sci 2: 84-88.

- Bhardwaj VK, Sharma KR, Luthra RP, Jhingta P, Sharma D, Justa A (2013) Impact of school-based oral health education program on oral health of 12 and 15 years old school children. J Educ Health Promot 2: 33.

- Haleem A, Siddiqui MI, Khan AA (2012) School-based strategies for oral health education of adolescents-a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health 12: 54.

- United States General Accounting Offices (2000) Oral health: dental disease is a chronic problem among low-income populations. Report to Congressional Requesters. Washington DC, USA.

- Kwan SYL, Petersen PE, Pine CM, Borutta A (2005) Health-promoting schools: an opportunity for oral health promotion. Bull World Health Organ 83(9): 677-685.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global Standards for Health Promoting Schools, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Local action creating health promoting schools, Geneva.

- World Health Organization–Western Pacific Region (YEAR) Urbani school health kit teacher’s guide. Manila, Philippines pp. 1-19.

- D’Cruz AM, Aradhya S (2013) Impact of oral health education on oral hygiene knowledge, practices, plaque control and gingival health of 13- to 15-year-old school children in Bangalore city. Int J Dent Hyg 11: 126-133.

- Haleem A, Khan MK, Sufia S, Chaudhry S, Siddiqui MI, Khan AA (2016) The role of repetition and reinforcement in school-based oral health education-a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 16: 2.

- Tome G, Matos M, Simoes C, Diniz JA, Camacho I (2012) How can peer group influence the behavior of adolescents: explanatory model. Glob J Health Sci 4: 26-35.

- Sabbahi DA, Lawrence HP, Limeback H, Rootman I (2009) Development and evaluation of an oral health literacy instrument for adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 37: 451-462.

- Singh H, Kabbarah A., Singhal S (2017) Evidence brief: behavioural impacts of school-based oral health education among children. Toronto, Canada pp. 2-16.

- Ueno M, Takeuchi S, Oshiro A, Kawaguchi Y (2013) Relationship between oral health literacy and oral health behaviors and clinical status in Japanese adults. J Dent Sci 8(2): 170-176.

- Ministry of Education; Nay Pyi Taw (2016) Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. National Education Strategic Plan 2016-21 Summary. Naypyidaw, Myanmar pp. 1-60.

- Aung EE, Maung K, Zaitsu T, Kawaguchi Y (2018) An overview of oral health situation and challenges in Myanmar. Asian J Res Med Med Sci 1: 1-10.

- Latt NN, Cho SM, Htun NMM, Saw YM, Myint MNHA, et al. (2016) Healthcare in Myanmar. Nagoya J Med Sci 78: 123-134.

- (2012) World Health Organization (WHO) Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Health education: theoretical concepts, effective strategies and core competencies. Geneva.

- Thwin KM, Zaitsu T, Ueno M, Kawaguchi Y (2018) Effects of oral health education in Myanmar preschool children and guardians. J Investig Clin Dent 9: e12346.

- Kyaw Myint ZC, Zaitsu T, Oshiro A, Ueno M, Soe KK et al (2019) Risk indicators of dental caries and gingivitis among 10-11-year-old students in Yangon, Myanmar. Int Den J 70(3): 167-175.

- Ueno M, Takayama A, Adiatman M, Ohnuki M, Zaitsu T, et al. (2013) Application of visual oral health literacy instrument in health education for senior high school students. Int J Health Promot Educ 52: 38-46.

- Macek MD, Haynes D, Wells W, Bauer-Leffler S, Cotten PA, (2010) Measuring conceptual health knowledge in the context of oral health literacy: preliminary results. J Public Health Dent 70: 197-204.

- (2013) World Health Organization (WHO). Oral Health Surveys: Basic-Methods, 5th edition. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Greene JC, Vermillion JR (1964) The Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. J Am Dent Assoc 68: 7-13.

- Massler M, Schour I (1952) Epidemiology of gingivitis in children. J Am Dent Assoc 45: 319-324.

- Keikhaee R, Rakhshani F, Fijan S, Keikhaee M, Rad J, Roostaee F (2014) The effectiveness of oral health education by peers on knowledge and performance of students in Zabol, Iran. Int J ResMed Sci 2: 222-227.

- Saxena V, Jain M, Tiwari V, Torwane NA, Sharva V, De J et al (2015) Oral health promotion by peer group model approach among orphanages in Bhopal City, Central India. J Orofac Res 5: 77-79.

- Sushanth VH, Krishna M, Suresh Babu AM, Prashant GM, Chandu GN (2011) A peer group approach model of oral health promotion among orphans at Puduchery, South India. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 1: 71-75.

- Arora A, Khattri S, Ismail NM, Kumbargere Nagraj S, Prashanti E (2017) School dental screening programmes for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12: CD012595.

- Naidu J, Nandlal B (2017) Evaluation of the effectiveness of a primary preventive dental health education programme implemented through school teachers for primary school children in Mysore City. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 7: 82-89.

- Preethi S (2015) Dental health education and the role of teachers in imparting oral health education in Indian schools. J Educ Ethics Dentistry 5: 57.

- Conrado CA, Maciel SM, Oliveira MR (2004) A school-based oral health educational program: the experience of Maringa-Pr, Brazil. J Appl Oral Sci 12: 27-33.

- Redmond CA, Bkinkhorn FA, Kay EJ, Davies RM, Worthington HV, et al. (1999) A cluster randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of a school-based dental health education program for adolescents. J Public Health Dent 59: 12-17.

- Haque SE, Rahman M, Itsuko K, Mutahara M, Kayako S, et al. (2016) Effect of a school based oral health education in preventing untreated dental caries and increasing knowledge, attitude, and practices among adolescents in Bangladesh. BMC Oral Health 16: 44.

- Mbawalla HS (2013) Planning, implementation and evaluation of a school program to promote oral health among Tanzanian adolescents [dissertation]. University of Bergen, Norway.

- Angelopoulou MV, Kavvadia K, Taoufik K, Oulis CJ (2015) Comparative clinical study testing the effectiveness of school based oral health education using experiential learning or traditional lecturing in 10-year-old children. BMC Oral Health 15: 51.

- Hartono SW, Lambri SE, van Palenstein Helderman WH (2002) Effectiveness of primary school based oral health education in West Java, Indonesia. Int Den J 52: 137-143.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...