Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Clinical Case(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Early Third Molar Extraction: When Germectomy Is the Best Choise Volume 4 - Issue 4

Jo Se Rim1 and Hee Ja Na2*

- 1Department of Dentistry, San Raffaelle University of Milan, IRCCS San Raffale Hospital, Italy

- 2Oral Surgeon Rome, Italy

- 3Professor of Surgery Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Surgery School of Medicine, University of Miami Florida, USA

Received: July 23, 2020; Published: August 10, 2020

*Corresponding author: Cardarelli Angelo, Specialist in Oral Surgery, Adjunct Professor, Department of Dentistry, San Raffaelle University of Milan, IRCCS San Raffale Hospital, Italy

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2020.04.000192

Introduction

Third molars are often removed in order to prevent complications and various other problems associated with impacted third molars and their removal. Abortion of mandibular third molars is a procedure carried out at an early age in those subjects where there is insufficient room for the eruption of the third molars. On the other hand, one can also decide to remove the second molars and to annex ate orthodontically the third molars in the arch.

Decision Making

The best time to perform a Germectomy is during one of the three stages of tooth development. The orthodontist will create a treatment strategy that will determine when the surgical phase should commence. While the need may no doubt exist, a global agreement exists on the fact that lower molars should be considered only one between several factors able to cause malocclusion. Thus, the germectomy of the third molars has to be performed only in carefully selected patients after a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation of the single case[1-4].It is also important to note that dental age and bone age to not always correspond with chronological age. In some children calcification of the tooth bud occurs early, while in other children it may be delayed[5-8].

Stage 1: 7-11 years old – Start of tooth bud calcification.

Stage 2: 12-15 years old –Crown mineralization is complete.

Stage3: 14-18 years old –Root formation partially complete.

This period is the most favorable for germectomy because the crypt’s bony cover is partially resorbed, and the crown is still in a submucosal position. While the tooth is retained inside its follicular membrane, there is no risk of infection. When extraction is called for, it is also preferable to operate before the crown has erupted. Doing so avoids peri coronal bacteria.

Surgical Protocol

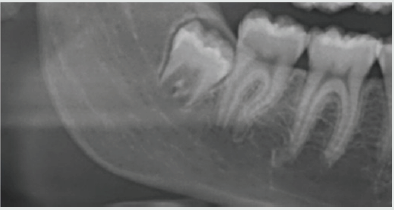

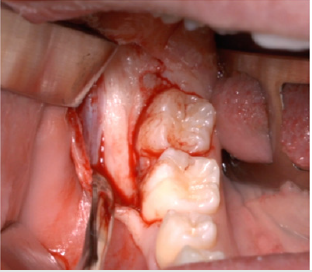

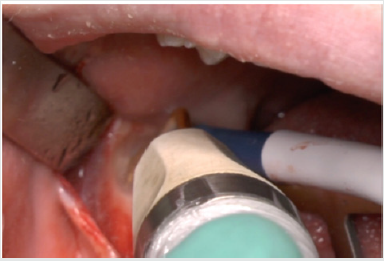

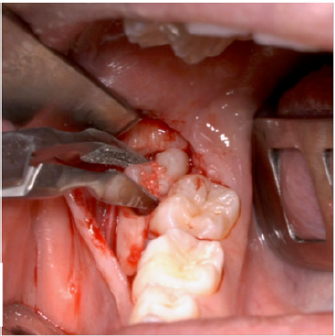

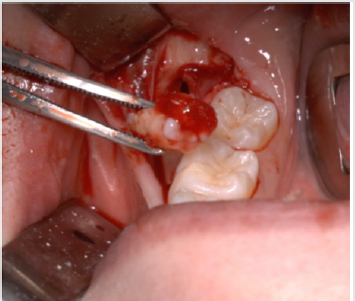

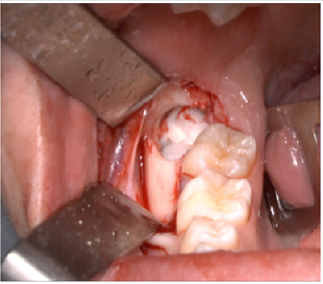

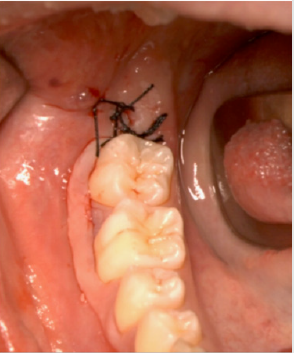

A full-thickness triangular flap is reflected ted with a horizontal incision at the base of the papillae between the sixth and seventh and a distal discharge incision with a vestibular pattern(Figures 1-4).Then we proceed with the osteotomy that can be performed with rotating instruments mounted on a straight handpiece or with a piezoelectric terminal with the dedicated(Figures 5 & 6). Tooth bud sectioning helps reduce the extent of bone removal required and is conduct- ed when the opening is too narrow for total eruption. The crown is secured with the sharp end of a fine elevator at a stage when the roots are not yet formed. The section is carried out from the outside to the inside using aspindle-shaped bur, starting from the previously exposed buccal portion.This section is always incomplete because it must not\reach the lingual wall of the bone crypt. The tooth is then fractured by using a straight elevator along the incision and the fragments are removed using suction cannula or curved hemostatic forceps.The alveolar cavity is cleaned with saline irrigation and filled with collagen sponge and the (4/0) sutures is performed(Figures 7-13).

Conclusions

Germectomy, or early third molar ex- traction, is generally indicated when inf lammation, edema, and pain are exhibited in the young adult patient. The clinician notes by both physical observation and panoramic X-ray that the space restriction will inhibit complete tooth emergence with normal dental and periodontal characteristics [2]. At this early stage of eruption, extraction is some- times associated with complications, chiefly from infection. Also, the surgical procedure may prove challenging. This is due to the nature of the complete root formation and root morphology relative to the mandibular canal. The periodontal environment may also be compromised by the resorption of the alveolar wall of its distal root. Thus, extracting before these challenges arise is the preferred option[9-10].

References

- Srivastava P, Shetty P, Shetty S (2018) Comparison of surgical outcome after imparted third molar surgery using piezotome and the conventional rotary handpiece Contemporary Clinical Dentistry 9(6): 318.

- Jiang Q, Qiu Y (2015) Piezoelectric versus conventional rotary techniques for impacted third molar extraction . A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicine 94(41): 1685.

- Al Moraissi EA (2015) Does the piezoelectric surgical technique produce fewer postoperative sequelae after lower third molar surgery than conventional rotary instruments ? A systematic rewiev and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 45(3): 383-391.

- Goyal M, Marya K. (2011) Comparative evaluation of surgical outcome after removal of impacted mandibular third molars using a Piezotome or a conventional handpiece : a prospective study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 50(6): 556-561.

- Benediktsdottir IS , Wenzel A, Petersen JK, Hintze H (2004) Mandibular third molar removal risk indicators for extended operation time postoperative pain and complications . Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 97(4): 438-446.

- Oikarinen K (1991) Postoperative pain after mandibular third molar surgery . Acta Odontol Scand 49(1): 7-13

- Rullo R, Addabbo F, Papaccio G, Daquino R, Festa VM (2013) Piezoelectric device vs Conventional rotative instruments in impacted third molar surgery: Relationships between surgical difficulty and postoperative pain with histological evaluations. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 41(2): 33-38.

- Mantovani E, Arduino PG, Schierano G, Ferrero L, Gallesio G, et al. (2014) A split-mouth randomized clinical trial to evaluate the performance of piezosurgery compared with traditional technique in lower wisdom tooth removal. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 72(10): 1890-1897.

- Arun K Garg (2017) Tooth Extractions, Socket Grafting and Third Molar Extractions. Group MIAMI pp. 240.

- A Cardarelli, Arun K Garg (2020) Piezolectric Surgery of Impacted Teeth.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...