Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6628

Case Report(ISSN: 2637-6628)

Meningoencephalitis and Spontaneous Acute Subdural Haematoma Complicating COVID-19: Report of an Unusual Case and Review of Literature Volume 5 - Issue 1

Muneer Abubaker1, Afshan Hasan1, Suhail Hussain2, Yahya Paksoy3 and Abdul Rafi Mohammed1*

- 1Consultant Family Physician, Primary Health Care Corporation, Qatar

- 2Consultant Stroke Physician, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

- 3Consultant Neuroradiologist, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

Received: January 25, 2021; Published:February 04, 2021

Corresponding author: Abdul Rafi Mohammed, Consultant Family Physician, Primary Health Care Corporation, Qatar

DOI: 10.32474/OJNBD.2021.05.000205

Abstract

Neurological complications of COVID-19 are not uncommon and can sometimes be serious and even fatal. We report a case of COVID -19 complicated by meningoencephalitis and spontaneous subdural hematoma requiring emergency craniotomy. Patient had a stormy course in intensive care and eventually died. As far as the authors are aware only handful of COVID-19 patients complicated with subdural hematoma have been previously reported in the literature.

Keywords:COVID-19; Pneumonitis, Intensive Care; Subdural hematoma; Meningoencephalitis; Craniotomy

Introduction

The novel coronavirus SARS CoV2 was first identified in Wuhan, China in December 2019. Since then COVID-19 has become a global pandemic causing considerable morbidity and mortality especially in elderly and persons with underlying health problems such as diabetes. The spectrum of the clinical picture includes asymptomatic infection, mild respiratory symptoms, severe pneumonia, multisystem involvement and coagulopathy leading to intensive care admission. Reports of serious cerebrovascular and neurological complications associated with COVID-19 are still emerging.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old male with well controlled type 2 Diabetes, presented to primary care with fever, sore throat and cough. He had no exposure to COVID-19. His other co-morbidities included hypertension, dyslipidemia, and palpitations for which he was on Metoprolol. Clinically he was febrile but hemodynamically stable. SARS COV2 RT-PCR test was reported positive the following day. By then he developed dyspnea and was referred to secondary care emergency services where he was found to be febrile, tachypneic and desaturating on air. Chest x-ray showed bilateral diffuse patchy opacities suggestive of COVID Pneumonitis. The following day he deteriorated further and was shifted to intensive care.

Timeline of Significant Events in Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

Day 1: Admission to ICU, respiratory support with Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV). Chest x-ray worsened and commenced on Remdesivir, cefuroxime and dexamethasone.

Day 4: Intubated due to restlessness and tachypnoea. ECG showed ST elevation, Troponin rose to 79 from 10. Bedside echo showed no wall motion abnormality, good LV contractility and no pericardial effusion. Cardiologist opined this to be likely myopericarditis.

Day 5: Developed SVT which settled with carotid massage.

Day 10: AF with rapid ventricular response and hemodynamic instability. Reverted to sinus rhythm after three DC shocks and Amiodarone.

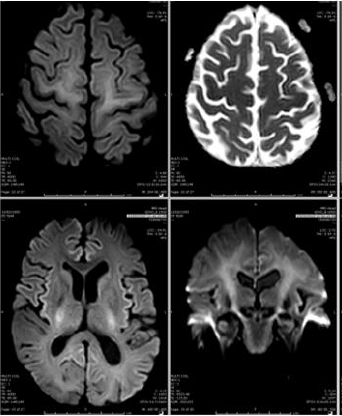

Day 11: Non enhanced CT scan brain done for suspected encephalitis, reported normal. MRI brain indicates COVID-19 encephalopathy (Figure 1).

Day 12: Hypokalemia induced VT. Treated with DC shock and started on Amiodarone and Colchicine.

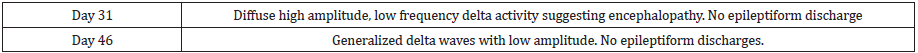

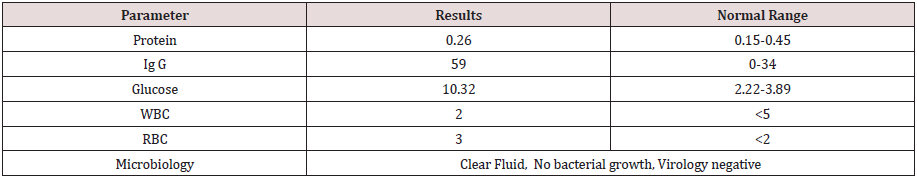

Day 21: Unconscious despite stopping sedation, EEG (Table 1) CSF analysis (Table 2) indicated COVID related encephalopathy.

Day 24: Metabolic acidosis corrected by dialysis. AF with hypotension, treated with two DC shocks and Amiodarone, reverted to sinus rhythm.

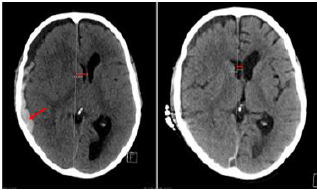

Day 29: Developed unequal pupils and low GCS. CT head showed Right acute subdural hematoma (Figure 2).

Day 30: Emergency right craniotomy and evacuation of SDH. Day 36: Developed tachypnea. CTPA showed no evidence of pulmonary embolism.

Day 62: Oliguria with volume overload. Commenced dialysis with vasopressor support.

Day 66: Rising inflammatory markers and worsening chest x-ray.

Day 72: Hypotension and bradycardia followed by PEA. Patient died despite resuscitation.

Figure 1: Non enhanced MRI brain Diffuse weighted images ( show perirolandic and bilateral corticospinal hyperintensity without diffusion restriction indicating COVID 19 encephalopathy. But there was no susceptibility on SWI (susceptibility weighted imaging) indicating any hemorrhage.

Figure 2: CT head on the left shows right acute subdural hematoma (red pointed arrow) measuring 18 mm in maximal thickness causing 13 mm leftward midline shift (red straight line). Post craniotomy CT Head on the right shows interval re expansion of the right lateral ventricle, left sided midline shift reduced to 5.5 mm (redstraight line)

Discussion

With the rising number of COVID-19 cases throughout the

world, neurological involvement is being increasingly recognized

as a complication associated with it. A recent systematic review

of 225 case studies, showed neurological manifestations ranging

from mild symptoms like anosmia, ageusia and headache to

serious complications such as stroke, altered sensorium, seizures

and encephalopathy [1]. The mechanisms through which SARSCoV-

2 affects the Central Nervous System (CNS) are not yet fully

understood. Possible routes for viral spread are hematogenous

spread, direct spread to the brain crossing the blood brain barrier

and spread through neuronal pathways [2]. The target receptor for

the coronaviruses is the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE

2) receptor which is also found in the glial cells of the brain and

spinal cord tissues. The other mechanisms of brain injury include

cytokine‐mediated systemic inflammation (cytokine storm) and

hypoxic brain injury.

Clinical picture of COVID-19 related neurological manifestations

include polyneuropathy, encephalitis and acute ischemic or

hemorrhagic cerebrovascular events involving both peripheral

and central nervous system [3]. COVID-19 ischemic strokes are

more common than hemorrhagic strokes, and the average time

from diagnosis of COVID-19 to an ischemic stroke in one study

was about 10 days [4]. A panel of experts from World Stroke

Organization reported the risk of ischemic stroke during COVID-19

to be around 5% [5]. Intracranial hemorrhage in COVID-19 disease

has been linked to cytokine storm or coagulation abnormalities [6].

COVID-19 is associated with a prothrombotic state and severity

of this is linked to the elevated D-dimer levels [7]. Apart from

coagulation abnormalities, the other laboratory parameters which

are reported to be deranged in COVID-19 patients with neurological

involvement include elevated levels of Interleukin-6, procalcitonin,

C-reactive protein and blood urea nitrogen. decreased lymphocytes

and platelets compared to patients without CNS manifestations [8].

Our patient also had deranged clotting profile, raised CRP, raised

procalcitonin high D-dimer and thrombocytopenia.

The diagnosis of COVID-19-related encephalitis can be

challenging as the definitive confirmation of viral encephalitis

depends mostly on isolation of virus from cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF). This is extremely difficult or almost impossible as SARSCoV-

2 virus dissemination is transient and it’s CSF titer may be

very low [9]. CSF analysis was done in our patient which revealed

normal cell count and no organism was isolated. Two case series

have been reported which involved analysis of CSF from 12 patients

where CSF had no white blood cells and the PCR assay for this

virus was negative [10,11]. Apart from encephalitis, neurological

complications include hemorrhage and infarction. In a multicenter

retrospective observational case series, 18 patients with COVID-19

infection developed intracranial bleed within 11 days. Out of these

6 had Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH), 11 had Subarachnoid

Hemorrhage (SAH) and 1 had Subdural Hemorrhage (SDH) [12].

ICH and SAH could possibly be linked to arterial hypertension which

can be induced by binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 receptors, and

thrombocytopenia [13]. ICH is linked with high mortality rates and

hence, patients who are considered as high risk with multiple comorbidities,

previous history of aneurysms and on anti-coagulants,

need to be identified, and early interventions can improve their

outcome [14].

It has been reported that traumatic SDH can be a rare presenting

feature of underlying COVID-19 infection [15]. But there was no

history of trauma in our patient and in fact the SDH in this case was

spontaneous. Atraumatic SDH can be associated with anticoagulants

but our patient was not on them. There have been reports of

association of SDH with coagulopathy which could be inherited as

well as acquired [16]. COVID related coagulation abnormality is a

well-recognized complication especially in patients on intensive

care [17] and this could explain the reason for the development of

SDH in our patient. Radmanesh et al reported a large retrospective

observational case series involving 241 COVID-19 patients who

underwent CT or MRI of the brain. The most common radiological

findings were nonspecific white matter microangiopathy (55.4%),

chronic infarct (19.4%), acute or subacute ischemic infarct (5.4%), and acute hemorrhage (4.5%). White matter microangiopathy

was associated with higher 2-week mortality in this study [18].

In our patient initial imaging showed age related involutional

changes with periventricular leukoencephalopathy secondary

to microangiopathy. He had a repeat CT scan 16 days later in

view of anisocoria and reduced GCS, which showed an acute

spontaneous right frontal Subdural hematoma with midline

shift. Subsequent imaging later also revealed features suggestive

of meningoencephalitis. The treatment of COVID-19-related

encephalitis is mainly supportive. A variety of treatments, including

high-dose IV steroids, IV immunoglobulin, and immunomodulators

(e.g., rituximab), have been tried in various cases, with somewhat

limited outcomes [19]. Treatment of SDH is either Craniotomy with

evacuation of hematoma or burr hole insertion with insertion of

drain [20].

Conclusion

Subdural hematoma as a complication of COVID-19 is extremely rare and is a part of the wide spectrum of neurological conditions seen in such patients. COVID-19 related neurological manifestations are being increasingly recognized but questions remain unanswered about the frequency and severity of neurological symptoms, the underlying etiology and sequence of disease progression. Hence further research is needed to understand the neurological complications of COVID-19. Patients with COVID-19 should be evaluated early for any neurological involvement, and timely workup is crucial to reduce subsequent morbidity and mortality.

References

- Sharifian Dorche M, Huot P, Osherov M, Wen D, Saveriano A, et al. (2020) Neurological complications of coronavirus infection; a comparative review and lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurol Sci 15(417): 117085.

- Baig AM, Khale eq A, Ali U, Syeda H (2020) Evidence of the COVID-19 Virus Targeting the CNS: Tissue Distribution, Host-Virus Interaction, and Proposed Neurotropic Mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci 11(7): 995-998.

- Umapathi T, Kor AC, Venketasubramanian N, Lim CC, Pang BC, et al. (2004) Large artery ischaemic stroke in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Neurol 251(10): 1227-31.

- Craen A, Logan G, Ganti L (2020) Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Case Report. Cureus 12(4): 7846.

- Qureshi AI, Abd-Allah F, Al-Senani F, Aytac E, Borhani-Haghighi A, et al. (2020) Management of acute ischemic stroke in patients with COVID-19 infection: Report of an international panel. Int J Stroke 15(5): 540-554.

- Yaghi S, Ishida K, Torres J, Grory BM, Raz E, et al. (2002) SARS2-CoV-2 and stroke in a New York healthcare system. Stroke 51(7): 2002-2011.

- Leonardi M, Padovani A, McArthur JC (2020) Neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19: A review and a call for action. J Neurol 267(6): 1573-1576.

- Gogia B, Fang X, Rai P (2020) Intracranial Hemorrhage in a Patient With COVID-19: Possible Explanations and Considerations. Cureus 12(8): 10159.

- Ye M, Ren Y, Lv T (2020) Encephalitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun 88: 945-946.

- Kandemirli SG, Dogan L, Sarikaya ZT, Kara S, Akinci C, et al. (2020) Brain MRI Findings in Patients in the Intensive Care Unit with COVID-19 Infection. Radiology 297(1): 232-235.

- Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, et al. (2020) Neurologic Features in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. N Engl J Med 382(23): 2268-2270.

- Nawabi J, Morotti A, Wildgruber M, Boulouis G, Kraehling H, et al. (2020) Clinical and Imaging Characteristics in Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Acute Intracranial Hemorrhage. J Clin Med 9(8): 2543.

- Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Jiang C, Liu PP, Poutanen SM, et al. (2009) SARS-coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest 39(7): 618-625.

- Thompson BG, Brown RD, Amin-Hanjani S, Broderick JP, Cockroft KM, et al. (2015) A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 46(8): 2368-2400.

- Altschul DJ, Unda SR, de La Garza Ramos R, Zampolin R, Benton J, et al. (2020) Hemorrhagic presentations of COVID-19: Risk factors for mortality. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 198: 106112.

- Garbossa D, Altieri R, Specchia FM, Agnoletti A, et al. (2014) Are acute subdural hematomas possible without head trauma?. Asian J Neurosurg 9(4): 218-222.

- Levi M, Thachil J, Iba T, Levy JH (2020) Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Haematol 7(6): 438-440.

- Radmanesh A, Raz E, Zan E, Derman A, Kaminetzky M (2020) Brain Imaging Use and Findings in COVID-19: A Single Academic Center Experience in the Epicenter of Disease in the United States. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 41(7): 1179-1183.

- Ghosh R, Dubey S, Finsterer J, Chatterjee S, Ray BK (2020) SARS-CoV-2-Associated Acute Hemorrhagic, Necrotizing Encephalitis (AHNE) Presenting with Cognitive Impairment in a 44-Year-Old Woman without Comorbidities: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep 21: 925641.

- Pavlov V, Bernard G, Chibbaro S (2012) Chronic subdural haematoma management: An iatrogenic complication. Case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep 2012: 1220115397.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...