Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6070

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-6070)

The Effect of Culinary Techniques on The Composition (Lipid, Sodium, Fibers) of Different Prepared Dishes from Bombax Costatum, Cerathotheca sesamoïdes, Cassia Tora and sorghum in The Sudano-Sahel (Region of Cameroon)

Volume 4 - Issue 1M Dangwe1*, R A Ejoh1,2, C M Mbofung1,2

- 1Laboratory of Biophysics, Food Biochemistry and Nutrition, ENSAI, University of Ngaoundere

- 2University of Bamenda, Bambili

Received: May 10, 2021 Published: May 18, 2021

*Corresponding author: M Dangwe, Laboratory of Biophysics, Food Biochemistry and Nutrition, ENSAI, University of Ngaoundere, Cameroon

DOI: 10.32474/SJFN.2021.04.000176

Abstract

Chronic diseases are now the leading causes of mortality worldwide and represent 80% of death cases in developing countries [1]. The prevalence of chronic diseases related to diet is increasing generally in the world and particularly in Cameroon. Nowadays, many compositions of diet are changing due to urbanization. This work aims to determine the effect of culinary techniques on the chemical composition (lipid, sodium, fibers) of dishes with Bombax costatum, Cerathotheca sesamoïdes, Cassia tora and, sorghum in Sudano-Sahelian region of Cameroon. As part of the food consumed in the different families that constitute the sampling population, lipid content was found to be higher in stews of modern cooking techniques than in the old traditional cooking techniques. According to the Student test (P<0.05) stews cooked using the modern cooking techniques showed a significant difference to those cooked using the old traditional cooking techniques. The levels of lipid content in general increase for stews prepared using the modern method than in the old traditional method of cooking. For example, the lipid content in Cerathotheca sesamoïdes increases by 45±1. The content of crude fiber decreases from the old traditional method of cooking to that of the modern method of cooking. For example, Cerathotheca sesamoïdes ranges from 3.10 ± 0.6 to 1.60 ± 0.1 from the old to modern techniques. In general, the student test shows that the fiber content of stews with the old traditional method of cooking is greater than those of the modern method of cooking. In terms of minerals, there is an increase in sodium content from old to modern cooking methods in all the prepared stew that is 6522±156 to 7041±36 for Cerathotheca sesamoïdes. Also, new cooking methods are 114.42% times the sodium content of old cooking methods and the energy values of stew depend on the new culinary techniques, which can be higher compared to those of old culinary techniques.

Keywords:Chronic Diseases; Urbanization; Traditional Culinary Technique; Modern Culinary Technique

Introduction

During the entire human history, populations have experienced changes in ecological relationships that have modified their diet and physical activity and eventually altered their disease pattern [2]. Economic development together with recent technological innovations and modern marketing techniques have modified dietary preferences, and consequently, led to major changes in the composition of the diet. There was a shift towards high fat, refined carbohydrate, and low-fiber diet [3,4]. The dietary transition took place first in the industrialized world and the Sub-Saharan Africans are facing now this same problem in their countries. Indeed, Sub- Saharan African (SSA) is experiencing rapid demographic and epidemiologic transitions [5]. Urbanization is an example of social change that has a remarkable effect on a diet in the developing world [6]. These transitions are associated with increase susceptibility to non- communicable diseases (NCDs), dominated by cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and related risk factors: obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. Recent studies have mainly focused on the nutritional value of traditional dishes in other to fight against malnutrition in terms of deficiencies of food. The presence of malnutrition by exceeding energy intake than energy expenditure in leading to obesity is increasing in the World. This type of malnutrition is a worldwide problem in a developed country and is becoming a public health problem in developing countries [7]. Indeed, some studies show that traditional East African food habits are health benefits [8]. Other studies emphasize the nutritional value of dishes without considering the effects of cooking techniques on the level of nutrients in cooked products [9,10]. Nevertheless, there is a dearth of information on modification of the chemical composition of dishes of Bombax costatum, Cerathotheca sesamoïdes, Cassia tora with sorghum from the people of Africa and especially of Sudano-Sahelian of Cameroon due to urbanization. This purpose aims to determine the effect of culinary techniques on the chemical composition (lipid, sodium, fibers) of dishes with Bombax costatum, Cerathotheca sesamoïdes, Cassia tora, and sorghum.

Materials and Methods

Preparation and the collection of the dishes Identification of the recipes

An interview was carried out on several people from the Sudano-Sahelian Region (Mayo-Danay–Mayo-Kani) and after seeing the modifications of food habits in this region. It was necessary to base this work on the declaration of people born before 1951, who do not know how to read and write. The memory of people between 60 years and above were considered as that of children under 5 years meanwhile people within 35 years, were considered as children under 15 years old.

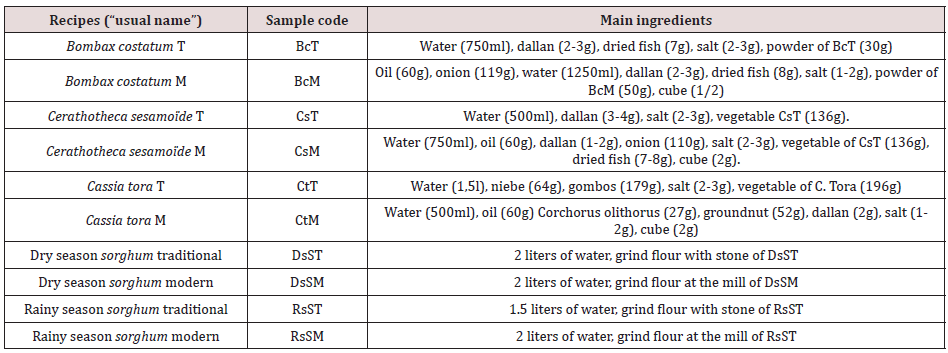

Food samples

The main vegetable and flowers much consumed by those populations are Cassia tora, Bombax costatum, Hibiscus esculenta, Cerathotheca sesamoïdes, Corchorus olithorus accompanied with flour from two species of sorghum (the rainy and the dry season sorghum). The dishes selected with vegetables were collected in the houses of people from this region and among these three types of dishes (Cassia tora, Bombax costatum, Cerathotheca sesamoïdes) were cooked with the different culinary techniques twice. In order to have a good result, the food collected from the houses of women (60 years old) staying in the rural area was considered as “traditional diet” meanwhile the dishes collected from the houses of young women (15-34 years) staying in the urban area were identified to be modern diet. These different samples collected from many houses were put in plastic bags sealed and transferred to the Food Biophysics and Nutritional Biochemistry of the National School of Agro- industrial Sciences. Then the samples were kept in a freezer at -18 °C until analysis. However, the moisture content was determined on fresh samples Table 1.

Proximate and statistical analyses

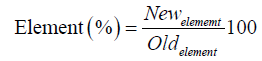

The moisture content was determined by drying in an ordinary Oven at 105 °C to a constant. The energy value was calculated using the Atwater coefficient. weight, ash determination was carried out by simple incineration in a furnace at 5500C for 48h. Lipid was determined using the soxhlet extraction method with hexane as the solvent [11]. The crude fiber was estimated following the acid digestion procedure of [12], and Carbohydrate by difference. Total nitrogen was determined after mineralization in concentrated sulphuric acid and colorimetric determination of ammonium following the procedure described by [13]. The crude protein was calculated as nitrogen*6.25. The mineral content (Na) was determined by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Buck Scientific model 210, USA). The energy value was calculated using the Atwater coefficient. The risk factors of the elements were calculated using the following formula:

Statistical analyses

The values were presented as means with their standard deviation (±SD). One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to test the effect of culinary techniques on the proximate composition of samples. When the effect was significant (P< 0.05) a student « T » was then used for the range test to compare two samples.

Results and Discussion

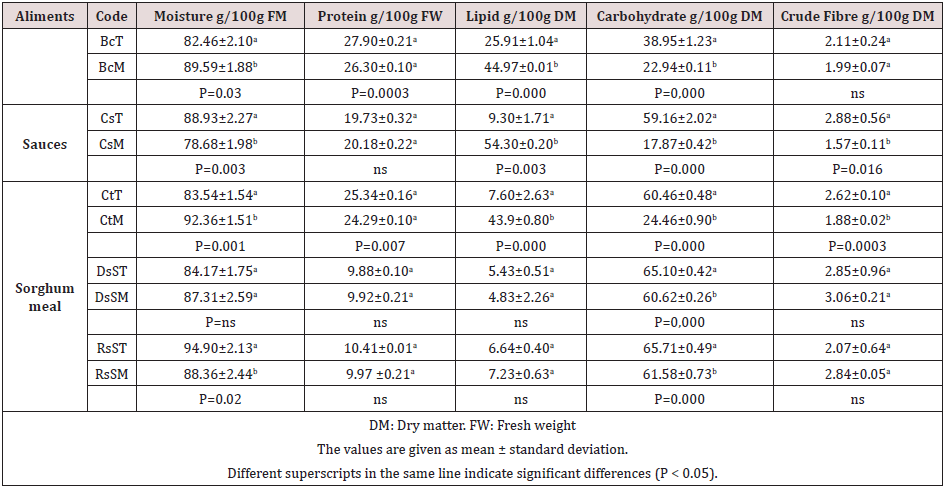

The proximate compositions of dishes are shown in Table 2. The moisture content of dishes is given in gram per 100g of fresh weight. This moisture content ranged from 78.68 to 92.3 g/100g F.W in the sauces and from 84.17 to 94.90 g/100g F.W in the sorghum meal. The student test shows that there is a difference between sauces of Bombax costatum, Cerathoteca sesamoïdes, Cassia tora, and sorghum meal gotten from the rainy season sorghum (RsS) (P<0.05) meanwhile there is no difference between sorghum meal of dry season sorghum (DsS). The moisture content of vegetables and flower of Cerathoteca sesamoïdes, Cassia tora, Bombax costatum are 85.39, 90.70, 95.54 [14-16]. The moisture content of the sauces was higher than those of the vegetables because much water and ingredients were used for the preparation of the sauces in respective of the traditional and modern culinary techniques. The protein content of the dishes ranged from 19.73±0.32% DM to 27.90±0.21% DM for the dishes containing sauces meanwhile those ranges from 84.17±1.75% to 94.90±2.13% deal with those dishes containing the sorghum meal [Table 2]. In general, there is no significant difference between all the dishes (p<0.05). The value of protein in the sauce of B. costatum while using the traditional and modern culinary techniques ranged from 27.90 ± 0.21% DM to 26.30 ± 0.10 % DM. Those of C. sesamoïdes in traditional and modern culinary technique ranged from 19.73±0.32% DM to 20.18±0.22% DM and the protein content of C. tora ranged from 25.34±0.16% DM to 24.29±0.10% DM with traditional and modern culinary technique. The protein content of vegetables and flowers of Cerathoteca sesamoïdes, Cassia tora, Bombax costatum are 5.6, 3.98, 23,92-24,15% [16-18]. In general, there is no significant difference between all the dishes (p<0.05). The value of protein in the sauce of B. costatum while using the traditional and modern culinary technique ranged from 27.90±0.21% DM to 26.30±0.10 % DM. Those of C. sesamoïdes in traditional and modern culinary technique ranged from 19.73±0.32% DM to 20.18±0.22% DM and the protein content of C. tora ranged from 25.34±0.16% DM to 24.29±0.10% DM with traditional and modern culinary technique. The protein content of vegetables and flowers of Cerathoteca sesamoïdes, Cassia tora, Bombax costatum are 4.2, 5.6, 3.98 [16-19]. These values are lower than those for the sauces cooked with these vegetables with their flowers. This can be explained by the fact that many other ingredients have been used for the preparation of those sauces (fish, bean (Vigna unguiculata) which is rich in protein) with the traditional and modern culinary techniques. There is no significant difference between the protein of dry season sorghum after using the traditional and modern setup (9.88±0.10% DM to 9.92±0.21% DM); and the Rainy season sorghum traditional and modern (10.41±0.01% DM to 9.97±0.21% DM). According to [20], the protein content of cereal ranged from 8 to 13% in general. The proteins obtain with our samples ranged from 9.92 to 10.41%. Protein is important for our organism for they are used for structures of the different part of our body [21]. Hence, according to the study of [22], whole grains of cereals protect the organism against non-chronic diseases. The lipid contents of the sauces varying from 7.60±2.63% DW (CtT) to 54.30±0.54% DM (CsM) from the sauces and the content of lipid of sorghum meal also range from 5.43±0.54 % DM (DsST) to 7.23±0.63% DM (RsSM). In general, there is a difference between all the dishes (P<0.05). The lipid contents of the sauces cooked with the traditional and modern culinary techniques are different (P<0.05). The lipid contents of flowers of B. costatum ranged varies from 25.91±1.04% DM (BCT) to 44.97±0.01% DM (BCM).

Meanwhile, those of vegetables of C. sesamoïdes ranged from 9.30±1.71% DM (CsT) to 54.30±0.20% DM (CsM) and the lipid content of vegetables of C. tora also range from 7.60±2.63% DM (CtT) to 43.93±0.80% DM (CtM). The values of lipid with the modern culinary technique are higher than those of traditional culinary technique. Cotton seeds oil and peanut paste are the main contributors to these high lipids contents of the sauces. The high content of lipid is transformed into triglycerides which are made up of a major portion of adipose tissue. High content of triglycerides in the body will develop non-communicable diseases. Hence, the lipid contents of the sorghum meal cook with the traditional and modern culinary techniques are not different (P>0.05). The lipid content of Dry season sorghum cooked using the traditional techniques ranged from 5.43±0.54 % DM (DsST) to 6.29±1.98% DM (DsSM) Dry season sorghum modern and the lipid content of Rainy season sorghum traditional (RsST) ranges from 6,64±0,40% DM to 7.23±0.63% DM. Meanwhile Rainy season sorghum modern (RsST) are similar. These values are higher than those found by Rooney et Serna- Saldivar, [23] of grain sorghum (3%) and can be explained by the different culinary techniques applied to these dishes. The carbohydrate contents of flowers of B. costatum ranged from 22.94±0.11% DM (BcT) to 38.95±1.23% DM (BcM). Those of vegetables of C. sesamoïdes ranged from 59.16 ±2.02% DM (CsT) to 17.87±0.42 % DM (CsM) and the carbohydrate content of vegetables of C. tora ranged from 60.46 ± 0.48% DM (CtT) to 24.46±0.90% DM (CtM). The differences observed in the sauces are due to culinary techniques apply to this preparation and to the types of ingredients which are different. On the other hand, the carbohydrate content of the Dry season sorghum meal drops from 65.71±0.49 % DM (DsST) to 60.62±0.26% DM (DsSM), and the carbohydrate contents for rainy season sorghum drops from 65.71±0.49% DM (RsST) to 61.58±0.73% DM to rainy season sorghum modern (RsSM). The carbohydrate contents of the sauces varying from 22.94±0.11% DM (BcT) to 60.46±0.48DM (CtT) from the sauces and the content of carbohydrate of sorghum meal ranged from 60.62±0.26% DM (DsSM) to 74.58±0.73% DM (RsSM). Indicating that there is a decrease in the carbohydrate content of the flour obtained from the old traditional method to the modern method. This can be explained by the fact that, in the old traditional method. The flour is eating whole without sieving while with the modern method, the flour after milling is sieve before cooking, thus lost of some carbohydrates. Hence, the study of [24] shows that the consumption of whole grain reduces the risk of chronic diseases. The fibers content of the dishes ranged from 1.6±0.1% DM (CsM) to 3.06±0.21% DM (CsT) in the sauces and the sorghum meal to 2.07±0.64 meanwhile the rainy season sorghum traditional is 3.06±0.21% DM with that of the Dry season sorghum modern. In general, the student “T” showed that the values of fibers are similar in the sauce of B. costatum and C. tora but not in the sauce of C. sesamoïdes. The value for the C. sesamoïdes ranged from 2.88±0.56% DM (CsT) to 1.88±0.02% DM (CsM). The fiber content of sorghum meals is similar. In the Dry season sorghum, the value ranged from 2.85±0.96% DM (DsST) to 3.06±0.21% DM (DsSM) and in the rainy season sorghum the value ranged from 2.07±0.64% DM (RsST) to 2.07±0.64% DM (RsSM). Fiber helps to regulate the digestive tract and keep people regular, and it reduces also non-chronic diseases.

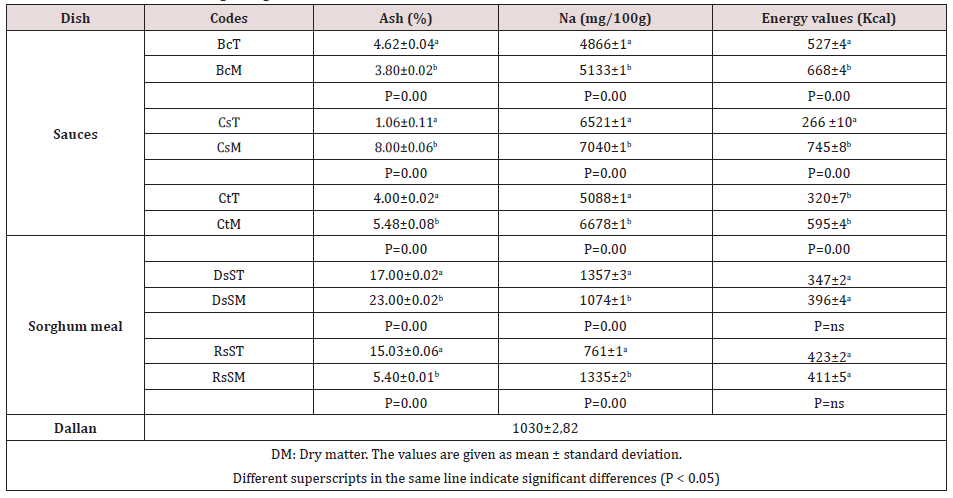

The fibers content of the dishes ranged from 1.6±0.1% DM (CsM) to 3.06±0.21% DM (CsT) in the sauces and the sorghum meal to 2.07±0.64 meanwhile the rainy season sorghum traditional is 3.06±0.21% DM with that of the Dry season sorghum modern. In general, the student “T” showed that the values of fibers are similar in the sauce of B. costatum and C. tora but not in the sauce of C. sesamoïdes. The value for the C. sesamoïdes ranged from 2.88±0.56% DM (CsT) to 1.88±0.02% DM (CsM). The fiber content of sorghum meals is similar. In the Dry season sorghum the value ranged from 2.85±0.96% DM (DsST) to 3.06±0.21% DM (DsSM) and in the raining season sorghum the value ranged from 2.07±0.64% DM (RsST) to 2.07±0.64% DM (RsSM). Fiber helps to regulate the digestive tract and keep people regular and it reduces also the nonchronic diseases. The micronutrient content of the dishes varied in Table 3 (P<0.05). The total ash content of sauces ranged from 1.06 ± 0.11% CsT to 8.00±0.06% CsM. The ash contents of flowers of B. Costatum ranged from 4.62±0.04% BcT to 3.80±0.02% BcM. The ash content of the sauce of C. sesamoïdes ranged from 1.06±0.11% CsT to 8.00±0.06% CsM and the ash content of vegetables of Cassia tora ranged from 4.00±0.02% to 5.48±0.08%. The ash content reflects the content in samples of minerals. These values are lower than those reported by [15,16] in ash content of flowers and vegetables of B. costatum, C. sesamoïdes, Cassia tora which are 9,22%, 9,11%, 12,53%.

The variations in ash are the function of ingredients and they are in situ ash content. The ash content of Dry season sorghum ranged from 17.00±0.02% DsST to 23.00±0.02% DsSM. The ash content of rainy season sorghum ranged from 15.03±0.06% RsST to 5.40±0.01% RsSM. These values are higher than those of [25] in the grain of sorghum which is 1.6%. This could be due to genetic, climatic, and edaphic environmental factors used that would influence the species used. The total sodium of flowers and vegetables in the dishes are varying (p<0.05). In general, the sodium content of B. costatum ranged from 4866±1mg/100g BcT to 5133±1mg/100g BcM. The sodium level of C. sesamoïdes ranged from 6521±1 mg/100g CsT to 7040±1mg/100g CsM and the sodium level of C. tora ranged from 5088±1mg/100g CtT to 6678±1mg/100gCtM. Nevertheless, the values of sodium are higher in the sauces of modern culinary technique B. costatum, C. sesamoïdes and, C. tora than those of traditional culinary technique. The high value observed in the modern culinary technique can be explained by the presence of ingredients like a salt, cube, dallan (1030±2,82mg/100g of sodium) which are rich in sodium.

The total sodium content of the sorghum ranged from 761±1mg/100g in rainy season sorghum (RsST) to 1357±3mg/100g in dry season sorghum (DsST). The sodium content of the sorghum meal from dry season sorghum ranged from 1357±3mg/100g (DsST) to 1074±1mg/100g (DsSM). The content of sorghum meal from rainy season sorghum ranged from 761±1mg/100g (RsST) to 1335±2mg/100g (RsSM). These values are higher than those found by [26] in the grain of sorghum with a value of 6mg/100g. But, in the rainy season sorghum with the traditional culinary technique, this value is higher than those of grain of sorghum. This could be justified by the milling of the grain sorghum. sorghum grain promotes the release of minerals during various technical treatments. Moreover, according to [27], the excess sodium content in the body will help to expand the blood pressure and the development of hypertension in these populations. Hence, the presence of sodium in excess in the blood will increase also the non-chronic diseases. The total energy of sauces varied in Table 4 (P<0.05). It ranged from 266±10kcal CsT to745±8 CsM. The energy level of B. costatum increased from 527±4kcal BcT to 668±4kcal BcM. The energy level of C. sesamoïdes increased from 266±10kcal CsT to 745±8kcal CsM and the energy level of C. tora increased from 320±7kcal CtT to 595±4 kcal CtM.

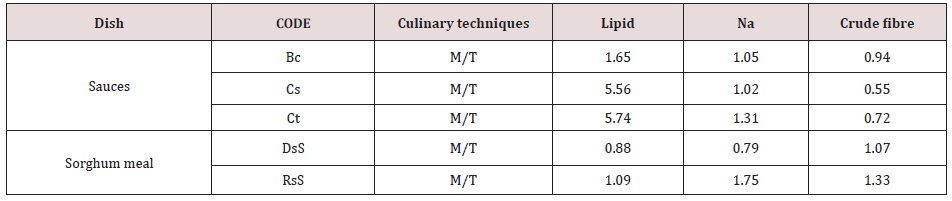

These values of energy are higher in the sauces of modern culinary techniques cooked in the urban area (B. costatum, C. sesamoïdes, C. tora) than those of traditional culinary techniques cook in a rural area. This result is similar to what has been reported by [28] in Tunisia who found that urbanization promotes the consumption of energetic food. The student test showed no significant difference between the energy content of sorghum. The energy content of the sorghum ranged from 347±2kcal in dry season sorghum (DsSM) to 423±2 kcal in rainy season sorghum (RsST). The energy content of the sorghum meal from dry season sorghum ranged from 347±2kcal (DsST) to 396±4kcal (DsSM) are similar. The energy content of sorghum meal from rainy season sorghum ranged from 423±2kcal (RsST) are similar to 411±5 kcal (RsSM). The food risk factor on a dish with modern culinary techniques has been evaluated on lipid, sodium, and crude fiber [Table 4]. The risk factor of lipid in sauces increased from 1.65 B. costatum to 5.74 C. tora. The risk factor of sodium in sauces increased from 1.02 C. sesamoïdes to 1.31 C. tora. The risk factor of crude fibers in sauces increased from 0.55 C. sesamoïdes to 0.94 B. costatum. In general, the modern culinary technique increases the food risk factor in sauces. The risk factor of lipid in sorghum meal ranged from 0.88 dry season sorghum (DsS) to 1.09 rainy season sorghum (RsS). The risk factor of sodium in sorghum meals ranged from 0.79 in dry season sorghum (DsS) to 1.75 in rainy season sorghum (RsS). The risk factor of crude fibers in sorghum meal ranged from 1.07 in dry season sorghum (DsS) to 1.33 in rainy season sorghum (RsS).

Conclusion

Modern culinary techniques sauces (B. costatum, C. sesamoïde, C. tora) are rich in lipid, sodium and have a low content of fiber, the energy value of these sauces are higher than that of the traditional culinary techniques. Traditional culinary techniques sauces are not rich in lipid, sodium but do contain much fiber in the sauce of C. sesamoïde. The modern culinary technique is richer in ingredients than the traditional technique. Nevertheless, our study confirms that there is a risk factor from food sauces prepared from the new system of preparation in the urban area, which is the Sudano-Sahel region of Cameroon.

Conflict of interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mazzucca Stephanie, Elva M Arredondo, Deanna M (2021) Expanding implementation research to prevent chronic diseases in community settings. Annu Rev Public Health 42: 135-158.

- Lucia F, Perry GH, Rienzo ADI (2010) Evolutionary Adaptations to Dietary Changes. Annu Rev Nutr 30: 291-314.

- Maire Bernard (2008) Que savons nous de l’alimentation des migrants? IRD Unité de Nutrition B. P. 64501, 34 394 Montpellier cedex 05. Institut français pour la nutrition (ifn).

- Raquel PF, Guiné Sofia G, Florenca, Maria Joao Barroca, Ofélia Anjos (2021) The duality of innovation and food development versus purely traditional foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology 109: 16-19.

- Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd Allah F, Abera SF, et al. (2017) Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 70(1): 1-25.

- Theodora Ismene Gizelis, Steve Pickering, Henrik Urdal (2021) Conflict on the urban fringe: Urbanization, environmental stress, and urban unrest in Africa.

- Vassilakou T (2021) Childhood Malnutrition: Time for Action. Children (Basel) 8(2): 103.

- Verena R, Oltersdorf MU, Elmafa I, Wahlkvist ML, AOMD Fracp, et al. (2007) Content of a novel online collection of traditional east African food habits (1930s-1960s): data collected by the Max-Planck-Nutrition Research Unit, Bumbuli, Tanzania. Asia pac J Clin Nutr 16(1): 140-151.

- Kana sopp M, Gouado I, Teugwa Mofor C, Smriga M, Fotso M, et al. (2008) Mineral content in some Cameroonian households food eaten in Douala. African journal of Biotechnology 7(17): 3085-3091.

- Ponka, R Fokou E, Beaucher E, Piot M, Gaucheron F (2016) Nutrient content of some Cameroonian traditional dishes and their potential contribution to dietary reference intakes. Food Sci Nutr 4(5): 696-705.

- AOAC (1990) Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemistry. AOAC: Washington, DC.

- Wolf JP (1968) Manuel d’analyse des corps gras. Azoulay, France pp: 500-519.

- Devani MB, Shishoo JC, Shal SA, Suhagia BN (1989) Spectrophotometrical method for micro determination of nitrogen in Kjeldahl digest. Journal of Association of Official Analytical Chemists 72(6): 953-956.

- Tchiégang C, Et Aïssatou K (2004) Données ethno nutritionnelles et caractéristiques physico-chimiques des légumes-feuilles consommés dans la savane de l’Adamaoua (Cameroun).

- Nuha MO, Isam AMA, Etelfadil EB (2010) Chemical composition antinutrients and extractable minerals of Sicklepod (Cassia tora) leaves as influenced by fermentation and cooking. International Food Research journal 17(3): 775-785.

- (2013) CEREOPTA (Centre d’étude et de recherche sur l’économie et l’organisation des productions animales). 18: 50-53.

- Ndong M, Wade S, Dossou N, Guiro AT, Gning RD (2007) Valeur nutritionnelle du Moringa oleifera, étude de la biodisponibilité du fer, effet de l'enrichissement de divers plats traditionnels sénégalais avec la poudre des feuilles. African African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 7(3).

- Morakinyo TA, Akanbi CT, Adetoye OT (2020) Dring kinetics and chemical composition of ceratotheca sesamoides endl leaves. International Journal of Engineering Applied Sciences and Technology 5(4): 456-465.

- Bosch CH (2004) Acmella oleracea (L) RK Jansen In: Grubben GJH, Denton OA (Eds.), PROTA 2: Vegetables/Lé [CD-Rom]. PROTA, Wageningen, Pays Bas.

- Favier JC (1989) Valeur nutritive et comportement des céréales au cours de leurs transformations. Céréales en régions chaudes. AUPELF-UREF, John LibbeyEurotext pp: 285-297.

- Sullivan JR (2004) Digestion and Nutrition.Your body how it works. Chelsea house publishers. An imprint of Infobase Publishing, New York.

- Mellen PB, Walsh TF, Herrington DM (2008) Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. NutrMetabCardiovasc Dis 18(4): 283-290.

- Rooney LW, Serna Saldivar S (1991) Sorghum In: KJ Lorenz, K Kulp, (Eds.), Handbook of cereal science and technology p. 233-269. New York, Marcel Dekker.

- Slavin J (2004) Whole grains and human health. Nutr Res Rev 17(1): 99-110.

- Hulse JH, Laing EM, Pearson OE (1980) Sorghum and the millets: their composition and nutritive value. New York, Academic Press pp: 997.

- Henley ECRDLD, Rooney L, Dahlberg J, Bean S, Weller C, et al. (2010) Sorghum: An Ancient, Healthy and Nutritious Old World Cereal. United Sorghum Checkoff Program.

- Whelton Paul K, Chair Lawrence Appel, Ralph L Sacco, Cheryl AM Anderson, Elliott M Antman, et al. (2012) Sodium, Blood Pressure, and Cardiovascular Disease Further Evidence Supporting the American Heart Association Sodium Reduction Recommendations. Circulation 126(24): 2880-2889.

- Sellam EB, Et Bour A (2015) Double charge de la malnutrition dans des ménages marocains: Préfecture d’Oujda-Angad. Nutrition Clinique et Métabolisme 34: 23-30.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...