Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6070

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-6070)

Raya Indigenous Livestock Husbandry Practices in the Highlands of Southern Tigray, Ethiopia

Volume 1 - Issue 2Abraha Negash Gebrehiwot*

- Ethiopian Meat &Dairy Industry Development Institute, Ethiopia

Received: May 25, 2018; Published: June 05, 2018

*Corresponding author: Abraha Negash Gebrehiwot, Ethiopian Meat & Dairy Industry Development Institute, PO Box 1573, Debrezeit- Ethiopia

DOI: 10.32474/SJFN.2018.01.000109

Abstract

Raya indigenous livestock husbandry practices was conducted in Emba-Alaje Enda-Mekoni and Ofla Wereda of Southern Tigray, featured by mountain chains and located at 12°47’ N latitude 39°32’ E longitude. with the aim to determine constraints and opportunities that exist within the farming systems, for better targeted improvement and to design policies strategies to support peculiar livestock husbandry practice, since it is experiences of the greatest successes stories of developing country agriculture and one of the most unsung, especially in the disadvantaged marginalized areas. Single household respondent was used as sampling unit, using Proportional Probability to Size approach. Out of 156HHs, 73.5% were male headed while 26.5% female-headed. Educational status of HHs members was diverse that was composed of 12.8% educated while 41%HHs members were illiterate. Average family size was 4.6±1.84. 83.33%HHs used own family labour, while others use hired labour. Feeding, watering, barn cleaning, animal keeping, monitoring animal health, cow milking, and selling dung cake tasks of wives and children, while feed purchase, buying and selling animals were husband’s duty. Age at first calving was 3.5 years for local while 2.5years for exotic breeds and calving interval was similar 1.5 year. The average milk yield was 2±1 litres for Arado, 5±1 litres for jersey and 10±2 litres for Holstein Frisians. The average cattle herd size were 3+1 in urban, 4.67+4.93 in periurban and 3.75±2.12 in rural farms. There was significant (P< 0.05) difference for cattle breed in lactation length and milk yield but no remarked (p>0.05) difference in Wereda level. Housing system of the study areas were featured backyard compound in 62.18% of the respondents, partial shelter in 17.95% of the respondents and improved barn in 19.87% of the dairy farmer respondents. Alternative interventions for betterment of the indigenous husbandry practice is with the climate change are timely scenario.

Keywords: Raya, Indigenous livestock husbandry, Arado, Holestain fresian

Introduction

Domestication of ruminant animals and their use to produce milk, meat, wool, and hides represents one of the cornerstone achievements in the history of agriculture. The essential feature of the ruminant animal that has fostered its utility as a dairy animal is the presence of a large pre-gastric chamber where microbial digestion of feed particularly fibrous feeds not directly digestible by human, provides various fermentation products that serve as precursors for efficient and voluminous synthesis of milk. Without this symbiosis between animal and microbe, the dairy industry would not have developed, and indeed human culture would be vastly different in its food-gathering methods (Weimer and James, 2001).

In Ethiopia, the livestock production system, which is dominated by indigenous breeds of low genetic potential for milk production, accounts for about 98% of the country’s total annual milk production. The low productivity of the country’s livestock production system in general and the traditional sector in particular is mainly attributed to shortage of crossbred dairy cows; lack of capital by dairy producers, inadequate animal feed resources both in terms of quality and quantity; unimproved animal husbandry system; inefficient and inadequate milk processing materials and methods; low milk production and supply to milk processing centers; and poor marketing system. Making improvement interventions to the traditional sector is, therefore, crucial if development of the livestock sector of the country is targeted. Its large livestock population; the favorable climate for improved, high-yielding animal breeds; and the relatively diseasefree environment for livestock make Ethiopia to hold a substantial potential for dairy development. Considering the substantial potential for smallholder income and employment generation from high-value livestock products, development of the dairy sector can contribute significantly to poverty alleviation and nutrition in the country. With the present trend characterized by transition towards market-oriented economy, the dairy sector appears to be moving towards a takeoff stage [1].

Dairy enterprises are the “white gold” of many developing countries, creating pathways out of poverty while boosting better human nutrition and health, regular income generation, employment, crop farming, and natural resource management. The context for smallholder dairy development in Ethiopia has been changing rapidly, creating both new opportunities and challenges [2]. According to Mburu [3] characterization of smallholder dairy production systems in highlands is critical in understanding the constraints and opportunities that exist within the farming systems. It allows better targeting of dairy improvement research and development. Therefore, information obtained can be valuable for detailed analysis of constraints and opportunities found in smallholder dairy systems and to design policies and strategies to support smallholder dairy development programs in variable intensification that one has to be aware of the challenges of dairy which, is one of the greatest successes stories of developing country agriculture and one of the most unsung, especially in the disadvantaged marginalized areas.

The bulk of Ethiopian livestock’s provision to the economy is not properly identified in conventional national accounts as coming from livestock. These distortions are particularly acute for highland livestock production systems in which animal energy for transport and dung for fuel are as important as conventional milk and meat production [4] that confirmed less attention was given to the sector despite its indispensible contribution to the economy of the majority of dairy farmers and the nation.

Livestock production in Ethiopia is constrained by a multitude of technical, financial, institutional and socio-economic factors [5]. Coordinating inputs (knowledge, finance, social and political capital) of various actors and their expectations in a way to create best practices and innovations could contribute better exploitation of the resource [2]. ‘When there is no bridge, there is always other means!’ [1]. The marginalized disadvantaged dairy farmers did not have exposure and access to affordable improved technological facilities that enable livestock production ease and profitable; consequently they do act according to their local resources and custom which demand due focus and research.

In Ethiopia, particularly in the highlands of Southern Tigray where previous research is very meagre [5], the indigenous livestock husbandry system is very peculiar than any other areas since long period of time but the doubt is their extent of production in comparison to their demand, nutritional needs and economic values, that is why the objective of this paper has targeted on the main indigenous livestock husbandry practices in relation to the livestock resource potential. Thus this work was initiated with the following objectives:-

1. To identify indigenous livestock husbandry practices & constraints in the study area, and

2. To determine the livestock breed composition of the area

Materials and Methods

Description of the Study Area

The research was conducted in Emba-Alaje Enda-Mekoni and Ofla Wereda of Southern Tigray, from December 01, 2011 to February 30 2012, which are featured by mountain chains, where Maichew of Enda-Mekoni is located at 12°47’ N latitude 39°32’ E longitude and an altitude of 2450m.a.s.l. It has a rainfall ranging from 600-800mm , temperature ranging 12-24oC, and relative humidity of 80% , which is highly variable from year to year and erratic in nature. The district is located on about 90-180km south of Mekelle city and 600-690Km north of the capital city Addis Ababa. The study area is also categorized as one of the populated highland areas of the country where land per household is 0.8h. Korem of Ofla lay on 12029’N latitude, 39o32’E longitude and that of Adishehu of Emba-Alaje is located on 120 56’N latitude and 39029’E longitude [6].

Study Population and Sampling Procedures

Single household respondent was used as sampling unit and sample size determination was applied according to the formula recommended by Arsham [7] for survey studies:

SE = (Confidence Interval)/(Confidence level) = 0.10/2.58 = 0.04, n= 0.25/SE2 = 0.25 / (0.04)2= 156

Where, confidence interval=10% and confidence level=99%

Where: N- is number of sample size

SE= Standard error, that SE is at a maximum when p= q = 0.5, with the assumption of 4% standard error and 99% confidence level.

The total sample size was determined to be 156 for the household level interview. Proportional Probability to Size (PPS) approach for uniformity matters as Desalegn [8]. Three approaches namely, participatory rural appraisal for base line information and formal (diagnostic) survey using well-structured questionnaire, farm visit & group discussions of the entire system were used to generate qualitative & quantitative data.

Data Collection and Analysis

A translated pretested semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect information on quantitative and qualitative data: Demographic situations, level of education, type of dairy breed, production performance, production objectives, variety of products, husbandry system, major production constraints, livestock disease incidences; opportunities for improvement and other related issues.. For the field survey, the method of data collection used was single- visit-multiple-subject survey. Data collected were analyzed using Microsoft Excel [9] and Statistical Package for Social Sciences [10] computer software program. Survey results were summarized using descriptive statistics like mean, standard deviation, and percents; mean differences were tested using student’s t.

Result

Household Characteristics of Dairy Farmers

The results obtained on household characteristics are presented in (Table 1). As shown, 25.6% of the respondents were less than 40 years of age, 51.3% of them aged 41-60 years while those with the age of more than 60 were only 23.1%. Of the total households interviewed, 73.5% were headed by males the rest being female-headed. When the issue comes to literacy level, the educational status of the household members was diverse that was composed of 12.8% educated while 41% of the household members were illiterate (i.e., do not read and write). Average family size was 4.6±1.84 that ranged from 1 to 14. Labour use, 83.33% of the interviewed households used own family labour, where as the other proportion of them use hired labour in addition for dairy farming. Feeding, watering, barn cleaning, animal keeping, monitoring animal health, cow milking, and selling dung cake were performed mainly by wives and children, while feed purchase, buying and selling animals were responsibilities of the husband.

Indigenous Livestock Husbandry Practices in Highlands of Southern Tigray

Milking Procedure Practiced

Milking twice per day (morning and evening) was the tradition followed by all households. Among the respondent dairy farmers, 25% of both urban and periurban dairy farmers practice zero grazing and milk their animals at a regular time of the day to supply the product according to their customers demand (Table 2). Whereas the rest of the proportion do not follow regular time of milking apart from maintaining the frequency. The housing systems, the cleaning processes and the procedures followed by the household are predominantly traditional. Udder washing was practiced by 10.89% respondents, of which 23.10% were from Emba-Alaje, 35.3% from Enda-Mekoni, 29.4% were from Ofla urban and 8.6% were Ofla rural areas who introduced cross breed cows.

Feeding Practice

Crop residues from teff, pulses, barley, wheat and maize and sorghum plus hay and natural pasture are the major feed resources the study area. Coping mechanisms practiced in the study areas during feed scarcity were moving to areas with available feed termed as ‘urna’, providing grass harvested from sloppy hills. The other important feed resources include spineless and thorny Cactus while some do practice forage development minimally. The crop residue conservation practices followed by the farmers are subject to nutritional losses. In the urban dairy farming, use of concentrate feeds is a potential alternative through which productivity of cows can be improved; however, the high cost was a limiting factor. Majority of the dairy farmers use leftover house hold feeds such as hull of grain after milling. Hatela (slurry from local brew) was another form of concentrate feed available (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: Traditional crop residue storage practices and crop livestock interaction in the highland mixed farming.

Figure 2: Feed resources of straw hatela mix, straw and stover as well as grazing natural pasture (Adishehu) & thorny cactus treated by flame before chopping (Maichew).

Housing Systems

Housing system of the study areas were featured backyard compound in 62.18% of the respondents, partial shelter in 17.95% of the respondents and improved barn in 19.87% of the dairy farmer respondents. In Urban Emba-Alaje, 76.92% of the respondents practiced improved housing but not hygienic for they do not clean the barn because they deemed crucial bedding to absorb heat for the animals (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Housing systems of the study area: a) A night enclosure in Hashenge b) A modified house with partition for calf pen in Korem c) A modified house with plastic roof in Maichew model dairy farmer, and d) An improved barn in Maichew dairy union

Calf Rearing

Cattle are kept in barns under normal circumstances and calves are kept in houses until they are strong enough to bear the extreme climatic phenomena. Young animals are managed in a traditional way. Suckling calves are kept separate from their dams, except when calves are used to stimulate milk letdown. Traditionally, calve suckling practice is believed to stimulate milk letdown, prevent teat blockage and softened the teat for ease of hand milking. If the calf dies, the hide is stuffed with cereal straw or grass with four legs made of sticks, rubbed by salt so that the dam would lick it to simulate the presence of the calf and stimulate milk letdown. Young children and females in general do mostly attend calves near encampments. Herders are well aware of colostrum feeding for the new born animals and understand the beneficial effect on health of the young.

In all the rural and periurban areas calves are herded in group by child and/or widowed of misery part of the community and encouraged by providing milk of every Wednesday termed as ‘tseba rebue’, while urban areas do practice tethering in backyards. Overnight, calves do spent in calf pen (urban and periurban) or in the normal household home (rural areas) isolated from their dams or herd. In local cows majority of the dairy farmers responded until the cow become dry of that rejects her calf from suckling was related with end of lactation period. But those owners of exotic do practice 4-6 months suckling before weaning. Traditionally, the herders use different types of weaning methods. Weaning is performed by piercing the nose of the calf with thorns, twisting up the nose skin of the calves to prevent suckling (as this causes pain when the wounded nose touches the teat) and smearing of teats with animal dung (Figures 4 & 5).

Figure 4: An enforced weaning practice, where calf’s nose pierced with thorns and twisted up the skin to prevent suckling.

Figure 5: Calf rearing practice: a) A calf tied nearby to his dam a means of milk let down (Maichew) b) Calf tethered in shaded hay in Korem.

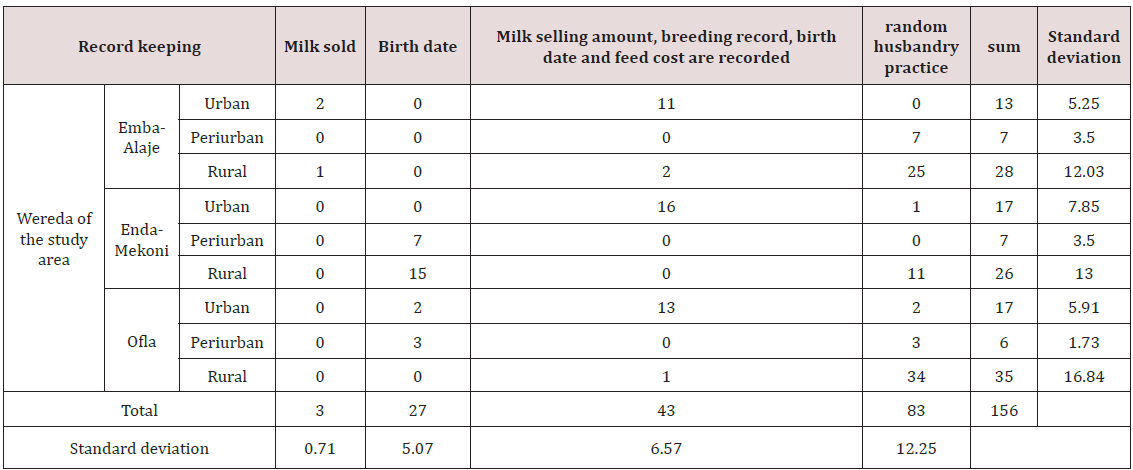

Record keeping

The most important record kept in the dairy farms was birth date that was considered in 44.9% respondents followed by 29.49% respondents to record amount of milk sold, 27.56% respondents used breeding record and 27.56% respondents used feed expenditure record, while 53.20% of the respondents do follow random husbandry practice. Breeding record, birth date and feed cost are recorded. Wereda level 72% of respondents from Enda-Mekoni, 33.33% respondents from Emba-Alaje and 32.76% of respondents from Ofla had record keeping trials (Table 3).

Milk Products Marketing

It was noticed that milk marketing was limited to urban and periurban areas but not in the rural districts. The major milk marketing challenges the respondents complained were 52.56% claimed cultural taboos and distance from market areas while 26.92% of the respondent dairy farmers blamed the discouraging market due to lower understanding of consumers to milk nutrition, poor talents of entrepreneurship of milk producers, and lack of road to transport milk from remote areas. Majority of the studied households reported that the demand for the milk products was high during dry season and low during wet season, besides to the fasting periods.

Dairy Farming Function and Performance

In the study area, the smallholders rear livestock for draught power, milk production, beef production and generate income through live animal sale, especially as a guarantee in case of risk. Also respondents indicated that cattle were used as manure for fertilizing the homestead farmland and compaction of seedbeds. Hide and skin of the animal was used either as source of cash income or used as household furniture such as grain storage, mat and to carry a baby on back of mothers locally termed as “delobo” Others: include manure, dung to smear floors and walls and also for fuel (for cooking purpose or to fire alternative thorny cactus feed). Concerning to dung utilization, 5% of Ofla Wereda respondents do practice biogas, while the rural Enda-Mekoni in vicinity to Ofla have exposure and were in infant stage unlike to Emba-Alaje Wereda where there was no dream of biogas. The interesting thing is dairy farmers exchange dung cake for hatela concentrate feed contracts in majority of urban dairy farms or else cover some part of household earning by selling particularly females of the household (Figure 6).

Figure 6: a) Hide locally used for mat and child bearing ‘delebo’ b) dung cake fuel a means of livestock by products exploitation , and c) Beast of animal-dairy farmers means of transport.

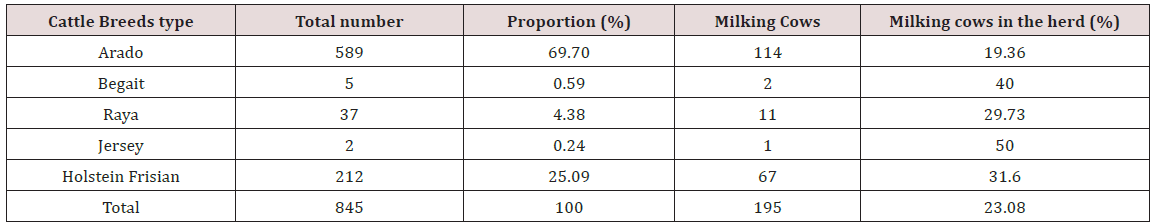

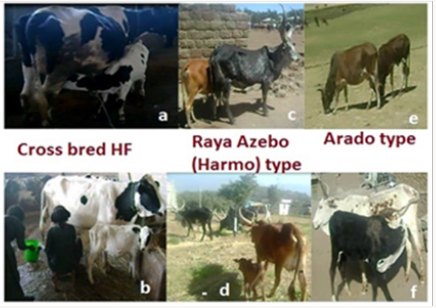

Age at first calving was 3.5 years for local while 2.5years for exotic breeds and calving interval was similar 1.5 year. The average milk yield was 21 litres for Arado, 51 litres for jersey and102 litres for Holstein Frisians. The average cattle herd size were 3+1 in urban, 4.67+4.93 in periurban and 3.752.12 in rural farms. The population of Holstein Frisian decreased from urban to rural while that of the Arado breed increased, indicating that dairy farming in rural destined on Arado while urban destined on Holstein Frisian breeds. Milking cows of the study areas were 23.1% out of 845 cattle owned by the respondents, which were composed of 631 local including Arado, Raya and Begait breeds and 214 crossbred of Holstein Frisian and Jersey upgraded cattle (Figure 7) (Table 4).

Figure 7: Dairy animals of the study area (a and b cross breed; C and d Raya or Harmo type and e and f refers to arado type dairy cows).

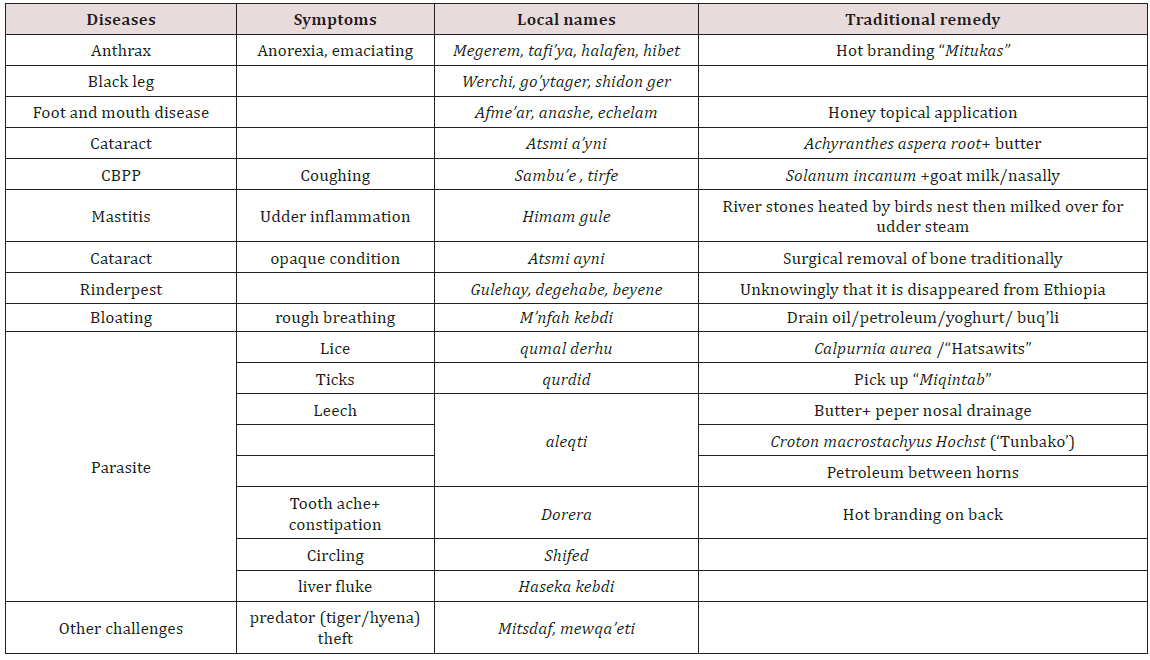

Animal Health Challenges

There was outbreak of FMD regional level, in particular, Emba- Alaje area but controlled due to regional vaccination campaign. In steep gorges of mountain area and less infrastructure, efficiency of the veterinary services or the veterinary personnel highly depends on the availability of facilities such as transportation, veterinary equipment, drugs. Besides, the farmers practice folklore medicine, to save their animals by bleeding, branding and use of herbal medicines. Urban dairy farmers do have better access to veterinary service that could be affordable in comparative to their income from milk. The steep gorges of the study area are part of animal and human hazard losses that enforced some farmers to stick on zero grazing. The author has also experienced to see severely broken or death of animals through falling in the steep gorges (Figure 8) (Table 5).

CBPP= Contagious Bovine Pleuro Pneumonia

Figure 8: Traditional Medication: a) Branding for inflammation; b) Hot branding for broken animals; c) for tafia (Anthrax), and d) Bleeding means of relif to extend life or act of Jewish slaughtering.

Discussion

The mean value of family size in the study areas 4.6±1.84 persons was comparable to CSA [6] report which was 4.5 for Enda- Mekoni, 4.29 for Ofla and 4.36 persons to a household for Emba- Alaje. This slight difference might be the reflection of the steady growth of the population. The proportion of the households who participated in the dairy technology package was 28.8%. In terms of labour use, 83.33% of the interviewed households used own family labour, where as the other proportion of them use hired labour in addition for dairy farming. Feeding, watering, barn cleaning, animal keeping, regulating animal health, cow milking, churning milk, milk selling and selling dung cake were more of performed by wife and children, while feed purchase, buying and selling animals as well as medication activities (bleeding and branding), were responsibility of the husband. Sell and purchase of dairy animals belong to the spouses more of men while women discharge feeding, milking and dairy products processing and selling. Herding to adolescents or hired in free grazing on communal natural pastures that constituted almost the only feed resource for all rural dairy farmers. Similar work by Girma, et al. [11] characterized that children are the primary care takers of cattle at day time. Rural dairy farms are characterized by roofless fenced enclosures to keep cattle during night times; calves being separated from adults and housed in the same shelter with households, however, dairy farming packaged households do abide by zero grazing and modified shelter for the hybrid Holstein Frisian cows.

Milking cows of the study areas were 23.1% out of 845 cattle owned by the respondents, which were composed of 631 local including Arado, Raya and Begait breeds and 214 crossbred of Holstein Frisian and upgraded Jersey cattle The result is indifferent from MoA (2004) report in Ethiopia that 11.82% of 2990 cattle population in 1998 was milking cows. That could be due to time difference and business mindedness of dairy farmers in urban agriculture now than draught oxen focus by the then time. The population of Holstein Frisian decreased from urban to rural while that of the Arado breed increased, indicating that dairy farming in rural destined on Arado while urban destined on Holstein Frisian breeds. Milking twice a day is similar to the milking frequency practiced in many parts of the country. Time of milking is normally early morning and late evening that is consistent with Sintayehu (2008). But time of the day particularly morning hours could vary that milking is delayed during cool seasons.

Average age at first calving was 3.5 years for local, while 2.5 years for exotic breeds and calving interval was similar 1.5 year. The lactation length was averaged 61 months for local cows while 81 months for exotic breeds that matched with Dawit (2009) report in Eastern Tigray who also summarized, milk yield of local breeds from 1.80.4 in Arado to 50.5 of Begait breeds. The average milk yield was 21 litres for local breeds, 51.5 litres for hybrid jersey and102 litres for hybrid Holstein Frisians. There was significant (P< 0.05) difference for cattle breed in lactation length and milk yield but no remarked (p>0.05) difference in Wereda level. Highest lactation length recorded in Maichew Holstein Frisian was 2 years, contrary to the universal record of 10 months exotic breeds, actually the cows displayed no observed heat. The study result disagreed with Mulugeta [12] who reported average daily milk off take from local cows 1.09 litres and crossbred cow 5.97 litres, with overall lactation length of both local and crossbred cows was 7.52±1.64 months as per farmer’s statements. Adebabay [13] recorded local cow’s milk yield of 1.46kg/cow/day. Genzebu (2012) in northern Tigray also added that Arado cows give an average milk yield of 1 - 2 liters/day for an average lactation period of 7.3 months.

In close affinity to Asfaw (2010) work in Arsi zone, generally more number of services per conception was reported using AI as compared to natural mating, attributed to inefficient AI services that included poor quality semen, poor heat detection techniques and inaccurate AI services. The same is true in feeding system that dairy producers practiced inadequate crop residue storage that hinders productivity of the animals. Similar to the reports of FAO, IDF [14] and Thapa (2000) dairy production was influenced by feed problem, poor animal health services and shortage of drugs, dissemination of poor genetic material, poor government attention to dairying, unreliable AI service, working land shortage to expand and/or forage development, market problems for dairy products, financial problem (absence of credit), waste disposal, lack of recording system (poor information flow), lack/poor extension service & training, lower understanding of the respondent, poor hospitality of AI/ veterinary renders. Traditional medication practice such as bleeding and hot branding that damage hide economy of the nation for unreliable remedy could be minimized as remarked PPLPI [15] by pen side diagnostics for common diseases.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Livestock production plays an important role in the socioeconomic and cultural life of the people inhabiting in the mountainous chains of the area. The cows fulfil an indispensable role for the dairy farmers serving as sources drought ox, milk food, income from sale of butter, the only determinant women hair lotion, source of dunk cake for family fuel and served as prestige and confidence to avert risks. The respondent remarked Wedi Lahimika for own bull and no one could cheer you what a cow could do indeed” to mean reliable resource and do have special dignity for the cow [16,17].

Establishment of dairy shades in the urban areas enabled to strengthen women economy who could not have initial capital and land access, to create employment opportunity and access of protein feeds to the other part of society. The marginalized disadvantaged dairy farmers do not have exposure and access to affordable improved technological products to handle and process their milk products where balanced scenarios are implemented by avoiding pasteurizing and packaging costs, raw milk markets offer both higher prices to producers and lower prices to consumers. Constraints of dairy farming involve higher cost of dairy cows, disease problems, fasting leads to poor milk demand, low productivity of the cows, technology to improve shelf life of milk products, fear of hazards, thefts and predators, and land scarcity particularly in the case of mountain area where fragmentation of land is distributed ‘gebo meqolo’ for landless youths. Steep cliff of the area has its own agro-ecological advantage, but featured by cattle falling hazards [18-21].

The amount of milk collected for a single churn varies with the number of milking cows and their productivity. Interventions in input supply system, production technologies, processing, and marketing practice including the crossbred heifer supply, AI and bull services, vaccination, emerging infectious animal diseases prevention and treatment, development of feed sources, access to dairy production technologies, access to market and market information and supportive infrastructure development, and capacity development on skills of dairy cows management are all in infant stage in the Wereda that demand integrated implementation.

1. To recommend possible interventions for the betterment of existing conditions

2. Further study on nutritional composition of cactus feed mixes.

References

- Zelalem, Yilma, Tadelle Dessie, Aynalem Hailu (2009) Public Private Partnership (PPP) A tool to bridge the mismatch between demand and supply of milk in Ethiopia.

- Tesfaye, Lema, Puskur R, Dirk Hoekstra, Azage Tegegne (2010) Commercializing dairy and forage systems in Ethiopia; An innovation systems perspective. IPMS of Ethiopian Farmers Project ILRI Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, pp. 57.

- Mburu L, Wakhungu J, Kang’ethe W (2007) Characterization of smallholder dairy production systems for livestock improvement in Kenya highlands. Livestock Research for Rural Development 19(8).

- IGAD (Intergovernmental Authority on development) (2008) Livestock Policy Initiative. Livestock Livelihoods and Institutions in the IGAD Region. Judith and Steven the IDL group. IGAD LPI Working Paper No.10- 8.

- MOARD (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development) (2007) Livestock Development Master Plan Study. Phase I Report-Data Collection and Analysis. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia pp. 1-68.

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia) (2007) Compilation of Economic Statistics in Ethiopia. CSA, Ethiopia, p. 2-10.

- Arsham H (2005) Questionnaire design and surveys sampling. USA.

- Desalegn, Genzebu, Mekonnen Hailemariam, Kelay Belihu (2012) Morphometric characteristics and livestock keeper perceptions of ‘Arado’ cattle breed in Northern Tigray, Ethiopia. Livestock Research for Rural Development 24(1).

- Microsoft Excel (2007) Microsoft Corporation, One Microsoft Way, Redmond, WA 98052-6399, USA.

- SPSS (statistical Package for Social Sciences) (2007) Statistical package for Social Science. (SPSS, 2007 version 16) for window Chicago, Illinois, USA.

- Girma, Kassie, Awudu Abdulai, Clemens Wollny, Workneh Ayalew, et al. (2011) Implicit prices of indigenous cattle traits in central Ethiopia: Application of revealed and stated preference approaches. ILRI Research report 26. Nairobi, Kenya.

- Mulugeta, Ayalew, Azage Tegegne, B Hegde (2009) Lactation performance of dairy cows in the Yerer watershed, Oromiya region, Ethiopia. In: Tamrat Degefa, Fekede Feyisa (2008) Commercialization of Livestock Agriculture in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP). Proceedings of the 16th Annual conference of the Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP) held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Adebabay Kebede, Firew Tegegne, Zeleke Mekuriaw, Azage Tegegne (2009) On-Farm Evaluation of the Effect of Concentrate and Urea Treated Wheat Straw Supplementation on Milk Yield and Milk Composition of Local Cows. 4(3): 55-56.

- FAO, IDF (2011) Guide to good dairy farming practice. Animal Production and Health Guidelines. FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) and IDF (International Dairy Federation) Rome, Italy.

- PPLPI (Pro-Poor Livestock Policy Initiative) (2009) Innovations for agricultural value chains in Africa. Applying science and technology to enhance cassava, dairy and maize value chains. Dairy value chain overview.

- Alganesh, Tola (2002) Traditional milk and milk products handling practices and raw milk quality in Eastern Wollega. Diredawa, Ethiopia, pp.108.

- Azage, Tegegne, Berhanu Gebremedhin, Hoekstra Dirk (2010) Livestock input supply and service provision in Ethiopia: Challenges and opportunities for market oriented development. IPMS, ILRI, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Delgado C, Rosegrant M, Meijer S (2002) Livestock to 2020: The Revolution Continues. World Brahman Congress, Rock Hampton, USA.

- Kelay, Belihu (2002) Analysis of dairy cattle breeding practices in selected areas of Ethiopia. Berlin, Germany.

- Payne W (1990) An Introduction to Animal Husbandry in the Tropics. New York, pp. 828.

- SNV (Netherlands Development Organization) (2008) Study on Dairy Investment Opportunities in Ethiopia. SNV, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. pp. 1-59.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...