Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6070

Short Communication(ISSN: 2638-6070)

How Healthy Was Diet in Genghis (Chinggis) Khan’s Horde in The 13th Century?

Volume 4 - Issue 5Denisenko Oleg*

- Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Received: December 20, 2022 Published: December 22, 2022

*Corresponding author:Denisenko Oleg, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

DOI: 10.32474/SJFN.2022.04.000196

Abstract

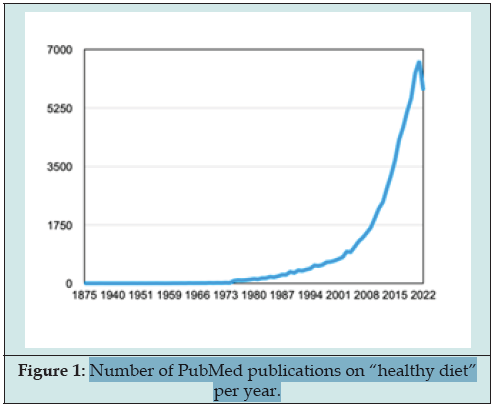

Healthy Diet

Healthy diet refers to the intake of certain nutrients that support healthy life and extend lifespan. PubMed search for “healthy diet” reveals a fast-growing interest in this issue during the last few decades (Figure 1). Studies support the notion that certain diets are positively associated with better health and lower risk of common non-communicable diseases, whereas suboptimal diets increase chances of such diseases [1]. To highlight the magnitude of the association, the EAT-Lancet Commission claimed that unhealthy diets pose a greater risk to morbidity and mortality than unsafe sex, alcohol, drug, and tobacco use combined (https://eatforum.org/ eat-lancet-commission/eat-lancet-commission-summary-report/). The definition of healthy diet is relatively dynamic, reflecting the ongoing evolution in understanding of the roles that different nutrients play in health and disease. Numerous articles and websites provide guidelines to help information seekers with food choices.

The Current Consensus of What Constitutes Healthy Diet Can be Found at the Centers of Disease Control (CDC) Website, it Includes

a) Fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fat-free or low-fat milk, and milk products

b) A variety of protein rich foods such as seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), soy products, nuts, and seeds.

c) Low amounts of added sugars, sodium, saturated fats, trans fats, and cholesterol.

(https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/healthy_eating/index. html). In further support, very similar food intake guidelines can be found in the Genesis.

Recently, the FDA updated the definition of the “healthy” nutrient content claim, which was previously set in 1994. This definition has limits for total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium. Foods must also provide at least 10% of the Daily Value (DV) for one or more of the following nutrients: vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, iron, protein, and fiber. The Mediterranean diet is considered one of the closest to an ideal diet. This notion is supported by the longevity and remarkable health of people living on the Mediterranean islands, including Crete and Icaria. Cretans, for example, lead the world in longevity with highest proportion of the population living past 100 years old. It is not surprising that their diet has attracted so much attention. With some differences between healthy nutrition recommendations, there is also an agreement that an excess of saturated fat and refined sugar should be avoided. Two successful diets discussed below challenge these recommendations and assumptions: a diet from 13th century Mongolia, and one followed by contemporary elite athletes.

Diet in the Genghis Khan Horde

While Mongolian culture itself has no records of eating habits in the 13th century, some information can be found in notes published by European travelers such as Marko Polo and John of Carpini, and in Chinese scripts from that time. They describe a Mongol diet of milk-derived products and all sorts of meat, but without bread, herbs, or vegetables [2]. According to CDC guidelines, this diet is far from being called healthy. Saturated fat from meat, for example, is associated with elevated risk of heart disease, therefore the American Heart Association recommends diets with no more than 5% of calories coming from saturated fat. Apparently, Mongols in Genghis Khan’s army had a substantially higher proportion of saturated fat in their diets. Were their unhealthy eating habits associated with an elevated risk of heart disease and a shortened life expectancy?

There can be no clear answer to this question due to a lack of data. However, we know that every Mongol from sixteen to sixty- one years of age was liable to military service [3] (https://www. worldhistory.org/Mongol_Warfare/). There is even a claim that the mandatory service age in Genghis Khan’s army was from 15 to 70 [4]. For example, one of his best generals, Subutai, retired at the age of 72. We can assume that an average 60-year-old Mongol male in the 13th century was sufficiently healthy and fit to serve in long distance operations and to be competitive in highly intense battles. Between military campaigns, Mongols exercised hard every day to maintain high fitness levels. For comparison, in the 21st century, members of the Armed Forces can retire after 20 years of service, with a mandatory retirement age of 62 for all officers other than generals or flag officers (US Army code). In this regard, there is no big difference between the US 21st and the Mongol 13th century armies. It is hard to compare health and fitness levels of a 60-yearold Mongolian warrior a thousand years ago and a same age officer in a modern army, but it is reasonable to assume that Mongols’ diet was adequate to maintain proper endurance and fitness levels that allowed their army to conquer vast lands of their continent.

Diet of elite athletes: Extensive research has been conducted on the impact of exercise on health and life span. Most studies agree that exercise improves multiple health parameters including decreased incidence of cancer. According to a recent comprehensive study, elite athletes have 5-fold lower all-cause mortality rates (including cancer) than people that do not exercise at all [5]. Even the adverse health impact of smoking is not as bad as lack of exercise. Not surprisingly, athletes live longer than the general population [6,7].

There is no one diet that all athletes use. Preferred food choices are aimed to maintain proper endurance and fitness levels. General considerations include higher carb consumption for energy needs and ingestion of certain protein amounts to maintain muscle mass. Thus, the best diet for an athlete is one that allows them to reach certain fitness goals, rather than one that follows CDC recommendations on healthy food choices. For example, to maintain a competitive long-distance running pace, an average runner needs to ingest 200-300 calories per hour, and most of these calories come from sugar rather than fat. To boost energy, runners use products like Gel 100 (100 calories) which contains 25g of added sugar per serving. It translates to 50-75g per hour, and more than a kilogram or sugar consumed by an ultramarathon runner per day. One can argue that they do not have ultramarathons every day but, like Mongolian warriors, elite athletes also exercise hard every day, with the difference that they consume somewhat less sugar per hour to maintain lower levels of activity. And yet, while eating unhealthy amounts of sugar, elite athletes stay healthy and live long.

Conclusions

On one hand, these examples highlight an obvious argument that calory consumption should not exceed energy expenditure, or how the CDC phrases it, “Stay within your daily calorie needs”. On the other hand, they indicate that instead of “healthy” or “unhealthy” diets, there are diets that serve to support certain activities or lifestyles. These examples also highlight the unknown relative contribution of nutrition, physical exercise, mental state and other factors to health and longevity. Are these factors independent of each other and how additive are their effects? For example, would a Mongolian warrior on a Mediterranean diet be able to serve in the army even longer and retire, say, around ninety? We cannot be certain, but there is no doubt that potential adverse consequences of “unhealthy” food consumption, intended or not, can be compensated by exercise.

Acknowledgements

Author is grateful to S. Stolyar for helpful discussions and A. Stolyar for manuscript editing, his research is supported by a grant from ISAC Program (NIDDK).

References

- Cena H, Calder PC (2020) Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for The Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 12(2): 334.

- Fenner JN, Tumen D, Khatanbaatar D (2014) Food fit for a Khan: Stable isotope analysis of the elite Mongol Empire cemetery at Tavan Tolgoi, Mongolia. J Archaeol Sci 46: 231-244.

- Martin HD (1943) The Mongol army. Royal Asiatic Society, London.

- May T (2007) Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley, pp. 1.

- Mandsager K, Harb S, Cremer P, Phelan D, Nissen SE, et al. (2018) Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness with Long-term Mortality Among Adults Undergoing Exercise Treadmill Testing. JAMA Netw Open 1(6): e183605.

- Garatachea N, Santos Lozano A, Sanchis Gomar F, Fiuza Luces C, Pareja Galeano H, et al. (2014) Elite athletes live longer than the general population: A meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 89(9): 1195-1200.

- Maron BJ, Thompson PD (2018) Longevity in elite athletes: The first 4-min milers. Lancet 392(10151): 913.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...