Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1381

Research Article(ISSN: 2644-1381)

The Role of cumulative ‘Hassles’ as a Potential Source of Mental and Physical Distress in Gulf War Health Professional Veterans Volume 3 - Issue 2

Deidre Wild*

- Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Coventry, UK

Received: August 21, 2020; Published:September 11, 2020

*Corresponding author: Deidre Wild, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Coventry, Coventry UK

DOI: 10.32474/CTBB.2020.03.000160

Abstract

Ninety-five Gulf War health professional veterans (HPVs) completed three six monthly postal questionnaires beginning in the Autumn of 1991. A part of these comprised repeated datasets for several aspects of inquiry for up to 5 time-phases that formed a trajectory from before to after the Gulf War (GW). The areas of inquiry of relevance to the focus of this article are changes to the HPVs’ belief in the morale justification for the war; attitude to life; need for formal counsel, and quality of sleep. Other stressor aspects that have already been published and could also have acted as “hassles” impacting upon the HPVs are summarized. In most instances, the quantitative data is illuminated by related qualitative comments. By viewing the potential ‘hassles’ as changes across time, it leads to the overall view that for a minority of HPVs, participation in the GW was a roller-coaster of disruption to mind and body. As such, the underlying ‘hassles’ need to be better understood in order to reduce them and their effects.

Keywords: Gulf War; health professional veterans; ‘hassles’

Introduction

Norwood and Ursano (1996) conceive the study of war stressors as evolving across a timeline of many different experiential phases, which they give as: pre-deployment; deployment; sustainment; hostilities; reunion, and reintegration [1]. In contrast, Dunning (1996) sees stressor change in participation in the GW by non-regular troops through their transition from pre-war citizen to deployment soldier to post war citizen, which has the chronology of war as implicit rather than explicit [2]. The nature of anticipatory stress in US combat and support troops, drawn from interviews conducted by Wright et al (1994) during and after the GW, although adopting a simple chronological approach of pre-deployment, through deployment and after the return home, further organized the findings under headings of adaptation; morale; cohesion; family relationships and concerns, and potential problems [3]. Whereas Gifford et al. (1996) extended their chronological approach by linking it to policy decision-making [4] and recommend that:...”rather than looking at the veterans of that war as products of events that occurred in a few weeks in January and February of 1991, we must consider the web of events that occurred over a much longer period from the decision to send forces to Operation Desert Shield through to their homecoming.” (Gifford et al, 1996) From a theoretical perspective, these authors share common ground for the study of modern warfare that broadens the reductionist research approach with its traditional tendency to focus upon combatants, males, and regular service personnel. They seek meaning from descriptive work that places emphases upon potential and changing GW stressors (in a context of time and place), concurrent with the responses of the veteran's bio-psychosocial changes [1-4]. In doing so, they also reflect changes in the fabric of the military culture in both the US and UK with the greater employment of women and in roles that unusually could take them to the front [5], and the use of non-regular soldiers to supplement and support regular service troops (such as those in this study) [6]. It has been said that the adverse health outcomes from the GW were not an expectation [7] given its short duration and swift military conclusion, its low casualty rates, and prompt return home of troops. Furthermore, that warfare has changed has been highlighted by Jones et al. [8]. They show that the proportion of military personnel involved in combat over the 20th Century has decreased with increased time, and the numbers of those in support roles has increased and continues to do so in terms of a new UK part-time Reserve force [9]. With this in mind, this article seeks to add to the responses to the question as to why some GW non-combatant veterans have been shown to be prone to post war mental and physical illness [10] when so few were directly involved in military action. In doing so, it will consider factors other than combat that could have contributed to this phenomenon. The research work of Kanner (1981) found that daily hassles significantly increase the chances of developing both physical and mental illness [11]. Later research by Bouteyre et al. [12] also supports the concept that there is a relationship between daily hassles and the development of health problems. Thus, these findings are relevant to the present study's findings from several areas of potential 'hassle' over and after the GW of 1991.

Methodology

Design

Using a retrospective and prospective design, comprising

three postal questionnaire surveys, each 6 months apart, the data

included in this article were collected for each of the following

time-phases:

a. before the war; deployment; 0-6 months post war (Return

home/Reunion) - Survey 1;

b. 7-12 months (Reintegration) - Survey 2,

c. 13-18 months post war (Aftermath) - Survey 3.

A small pilot study to refine the materials and identify and

agree the content preceded the main study.

Materials and Procedure

In all questionnaires, a ‘mix’ of quantitative and qualitative

data were collected to enable a greater depth of understanding

of the HPVs’ experiences than either method could produce when

employed alone [13]. Areas of inquiry for the purpose of this article

are as follows:

a. the HPVs’ changing opinion of the morality of the GW;

b. the need and reasons for formal counsel;

c. the HPVs ‘ attitude to life;

d. quality of sleep

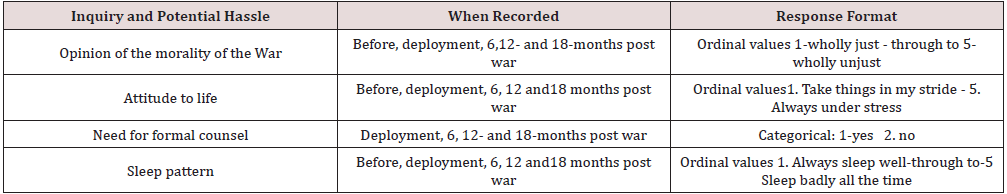

Table 1 provides the nature of the inquiry; time-phase when

recorded and the format of the data collected.

Participant sample recruitment procedure

The first 57 HPVs (47 Reservists and 10 Territorial Army) positively responded when contacted to join the study by an intermediary GW nurse veteran (known to the author), who held the target participants’ addresses. Through these first 10 TA participants a further 38 TA participants in similar GW roles were added using a snowball technique. In this way, comparable numbers of TA volunteers were recruited to that of the first group of Reservists (called up or volunteers). Finally, 5 Order of St John of Jerusalem Welfare Officer (all volunteers to the GW) joined the study voluntarily representing half of those who volunteered for the GW. The total of 134 contact letters issued across the three recruitment stages resulted in 95 consenting HPVs and gave an estimated minimum overall response rate of 71% from the three stages of recruitment. At the time of recruitment to the study, the number of volunteer TA and Reserve personnel deployed to the GW had not been reported in the public domain. Figures given some years after the GW suggest that the 95 HPVs in the participant sample represent some 9% of the total population of Reserve and TA (or similar voluntary military organization) deployed personnel [14].

Mode of Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using appropriate descriptive statistics. Qualitative data in the form of the HPVs’ comments were examined first by two researchers independently identifying then categorizing them into thematic groupings using key word or phrase labels. This thematic analysis has been described by several authors [15,16]. The comments then were then placed in their entirety within themes and subthemes by two independent researchers who made cross comparisons (and if necessary, reexamined the data) to reach consensus.

Ethical considerations

Although the principles adhered to early in 1991 preceded the formal ethical requirements of today’s research, the general principles of doing no harm; securing informed consent; the acceptance of autonomy overcompliance, and respect for rights to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality [17] were upheld throughout the research. Authoritative military and academic advice were taken throughout the study to avoid potentially sensitive issues. All information was forwarded to the HPVs cautioned them against breaching the Official Secrets Act. The data were held securely and in accordance with the Data Protection Act, 1987 and its update in 1998.

Results

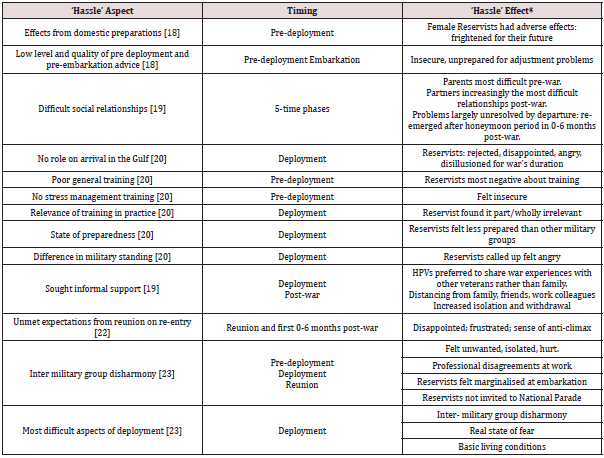

Summary of aspects of the GW as potential ‘Hassles’ (already published)

Table 2 gives a summary of other potential ‘hassles’ related to the GW that have already been published. Despite their tendency to be confined to one or more time-phases, they add to a context of adversity for some HPVs which may have lasting effects. The numbers in the first column refer to the publications which have been entered with corresponding numbers into the Reference List to aid further reading.

Change in the HPVs’ opinion of the morality of the war

Establishing the HPVs’ opinion of the morality of the GW over 4 (excluding deployment) of the 5-time phases was a means of gauging attitudinal change over time. As shown in Table 3, before mobilization to the war a large majority of the HPVs thought the war was a just cause and many embraced it during pre-deployment as an exciting opportunity. This remained the majority opinion (a just cause) but of a gradually dwindling number throughout the remaining time phases with the percentage of those with the opinion of unjust given before the War increasing overall by 23% by 18 months post war. To determine the significance of the direction of these data, the original 4 categories were transformed into two, comprising just and part/wholly unjust. When the 4 data entries were compared, the change in the HPVs' opinion of the justness of the war was significant (Q=11.85, df=3, p<0.05) Qualitatively, all of the related comments at 6 and 12 months post war were provided only by those who changed to being negative about the war from being positive before it. In the first comment, the HPV challenged the legality of the politics of the GW's origins and in the second another vented his personal frustration not having the opportunity to achieve what he perceived were the military goals, and as a consequence began questioning the morality of the war: “Political storm and ministerial inquiries over supply of arms for Iraqi munitions factories raises doubt over the justification of the War, although Iraqi invasion of Kuwait was still illegal”. (Male TA volunteer, senior officer doctor). “No, feel now unjust, mainly because of the failure to finish it - remove Hussain - and the lack of support offered to the Kurds. Makes me think that the effort to liberate Kuwait was undertaken more because of the potential loss of oil to the Western world and less because it was the right thing to do.” (Male TA volunteer, junior officer nurse). By 18 months post war, the comments became brief and blunt. These included the expression of strong and often bitter feelings of having been personally (all comments from Reservists) manipulated by the politics that led to war: “I feel we were used in a Petro-economic ploy disguised as a just cause.” (Male Reservist volunteer, senior other rank nurse) “Know what the media coverage was and now totally skeptical of political and military reasons.” (Female Reservist called-up, junior officer nurse) ”Unjust. I would not volunteer again. This was a political war concerned only with oil. It was a waste of life and resolved nothing. The politicians should hang their heads.” (Male reservist volunteer, senior officer, nurse)

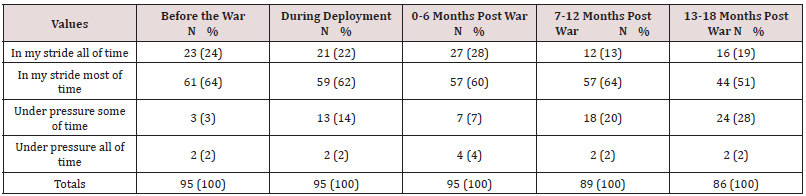

HPVs’ attitude to life from before to after the GW

As shown in Table 4, a majority of HPVs claimed that they took things in their stride all or most of the time in each of the time phases. However, those recording that they were under pressure some/all of the time (categories combined) during deployment represented 16% of the HPVs, but by 18 months post-war, the percentage figure for being under pressure some /all of the time had almost doubled to 30% of the HPVs. Thus reintegration, following the met or unmet expectations of earlier reunion in the first 6 months (often referred to as the honeymoon period), was marked by a sharp increase in stress that continued up to 18 months post war. It is of note that difficulty in relationships with partners [20] followed a similar post-war incremental upwards trajectory to that of being 'under pressure some/all of the time' (categories combined). The 5 sets of data for the HPVs’ attitude to life were compared using a Friedman Matched Test for the 86 HPVs who completed all of the data set, and a significant difference in attitude to life over time was found (÷ 2 = 23.34, df = 4, p < 0.001). There were few open comments provided by the HPVs for this data set across time. Perhaps the HPVs felt their chosen closed response was adequate, or perhaps there was some reticence to write about feelings that they may not have wanted to reveal or fully comprehend at that time. At six months post war, of the comments received, these two seem full of optimistic advice: ‘It has put life into perspective. If it is not as serious as a Gulf War issue, then it should not provoke too much worry. I am glad to be alive.’ (Male TA volunteer, senior other rank nurse) ‘To enjoy life and not to find problems that aren’t there.’ (Female Reservist called up, junior officer nurse) By 12 months, the tone in the comments received had changed with reference to the potential for post war-related mental health problems but applied to 'others', not herself.: ‘Definitely need more emphasis upon the psychological changes that may affect people.’ (Female TA volunteer, senior officer nurse) Similar to the preceding time-phase, of the few comments at 18 months, a retrospective understanding of how to protect a person's bio-psychosocial health during warfare seems to have been thought through but there was scant reference as to how to cope with post-war problems: ‘Counselling, reassurances, accurate information.’ 'Don’t go unless you really want to. Do a battle stress trauma course. Understand your motivations for going. Don’t take any extra emotional baggage with you.’ (Female volunteer, welfare officer). (Male Reservist called-up, junior other rank nurse).

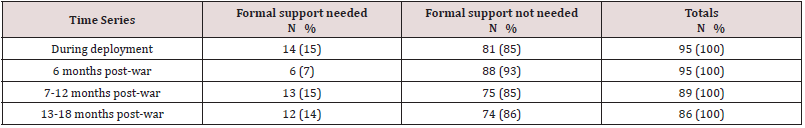

The HPVs’ requirement for formal counsel over the postwar time-phases

Frequencies and percentages of the HPVs who did and did not require formal counsel from during deployment to 18 months post War are given in Table 5. As can be seen in each time phase, a minority of the HPVs required formal counsel across the four-time phases. Of these, the percentage requiring such counsel was highest during deployment (17%) and lowest in the 0-6 months post War (6%). Of the post war time phases, the highest percentage of HPVs sought it during the 7-12 months (15%), in which the number was almost double that observed for the 0-6 months post war. Inferential statistics were not used due to the small numbers During deployment, fourteen HPVs (8 Reservists and 6 TA) recorded that they had received formal counsel during deployment via medical or self-referral to military personnel with a designated counselling role, i.e. commanding officers (CO), chaplains, medical officers, Welfare Officers, psychologists, and psychiatrists. Of this small number of recipients, 7 received counsel from an army chaplain, 3 from a nurse, and equal numbers from either their CO (2) or a psychiatrist (2). The low number of those requiring formal counsel was to be expected as it was known that within the military culture there was a reluctance to admit to problems that needed formal psychological help lest he or she be thought of as weak by peers. As an alternative, 38% of the HPVs sought informal support from colleagues during deployment and in the 3 successive post-war time-phases the percentages seeking informal support were much higher (23%, 24%, 27%, respectively) than for formal support in the same post-war time-phases. Of those who needed formal counsel, 10 (71%) were female officers of whom 5 were Reservists, 3 were TA and 2 were Welfare Officers. The remaining 4 were males in other ranks. None of the Reservist or TA officers sought counsel from a CO or used the Welfare Officers’ services (perhaps they did not want a record of their problems) but instead, 5 went to an army chaplain, 2 to a nurse, and one to a psychiatrist. In contrast, although none of the 4 male other rank HPVs consulted a chaplain or a Welfare Officer, two consulted their CO, one went to a nurse, and one to a psychiatrist: all of whom were ranked as officers. Thus, none of those in receipt of formal counsel used the services of the VS Welfare Officers whose key role was to provide counselling and none of the officers went to their CO whose role was that of a line manager. Nine of the female officers and one other rank male provided reasons for their formal counsel and its perceived usefulness. Of these, 2 comments were related to the intense fear reactions when under attack, as illustrated in one of these comments: “First night many SCUD alerts - no sleep for 48 hours. Then some joker shouted a hoax alert. I flipped! Went to the medical centre and stayed overnight and went on duty the next day. OK since then. Male nurse excellent but doctor not so helpful.”(Female Reservist called up, junior officer nurse) In contrast, the 2 Welfare Officers described their need for support from a chaplain to cope with the stresses of their own role: ‘I was the Red Cross [welfare support]. Went to chaplains - because they understood the pressures of a caring role.’ (Female Welfare Officer volunteer).

Three further comments express, an interpersonal problem at work from a male, other rank, CMT [counsel from an unhelpful CO]; difficulty with cultural differences associated with religion from a female junior officer, nurse [counsel from an unhelpful chaplain], and an unspecified family problem at home from a female junior officer, nurse [from a helpful nurse]. The remaining 3 comments, while providing little insight into the nature of the HPVs’ problems, indicated that neither the counsel received nor the counsellor was helpful, as illustrated in the following comments: ‘I spoke with clergy, not only for myself but for serving soldiers as a whole. The reply I got didn’t give me any comfort or support. Left questions unanswered.’ (Female TA VS, junior officer nurse) ‘The matron was the most unhelpful and unsympathetic woman I have ever met.’ (Female Reservist, junior officer nurse) Despite the small numbers, these findings suggested that for most of the HPVs in receipt of formal counsel during deployment, only two found it helpful and their counsellors empathetic. Officers seemed to show a preference for formal counsellors who were not related to their more senior chain of command. In the first 6 months post-war, comments from the HPVs who needed formal support did not described the nature of their ‘stress’ or ‘stressors’, despite providing testimony that they had experienced stress since returning home from the War: ‘Counsellor was very useful. I could relate to things that were discussed in relation to my war stress.’ (Female reservist volunteer, junior officer nurse) Furthermore, it was not clear in other comments if the HPVs associated participation in the War as a factor that amplified the effects of the resumption of the common life stressors of job change; job pressure, and bereavement, as described in the comment below: “Following the return from the Gulf I moved to a new [with the military] posting (2IC). This put an awful lot of pressure on me. I became very drained (ill) picked up a continual viral infection. I couldn’t work at who I was anymore. My self-concept just totally altered. In the end I went to a psychologist”’ (Female Welfare Officer volunteer) All of the 13 HPVs’ comments related to the 7-12 months post war provided war-related reasons as to why formal counsel had been needed. Of these, 11 express a mixture of health and social problems due to withdrawal: ‘Since coming home, sleeping problems leading to increased alcohol consumption to unacceptable levels.’ (Male Reservist called up, junior other rank CMT); ‘Feeling depressed and lonely. Lack of concentration at work - sent home. Also, relationship problems.’ (Female TA volunteer, junior officer nurse)), ‘Lack of confidence /self-esteem since coming home. Saw Doctor’. (Female TA volunteer, junior officer nurse). Two further comments indicate that although formal help from doctors had been sought, the advice/treatment was not taken or the HPV was dispatched without interest from the doctor: “Increasing depression, feeling under pressure - work and home. I refused the treatment offered as the GP merely wanted to give me anti-depressant tablets - they would not have helped.” (Female Reservist called up, junior officer nurse) ‘Unable to maintain interest in relationships, too restless to move on in all aspects of life - feel I am underachieving. Sought counselling about my feelings from doctor but he wasn’t interested.’ (Male Reservist called up, senior other rank nurse) A lack of coping with events at work that brought back unpleasant memories from war is referred to in the first comment. ‘Not coping well with constant death and bereavement on oncology unit. Feel it strongly relates to Gulf.’ (Female VS volunteer, junior officer nurse).

Only one comment focused upon financial hardship as a consequence of participation in the War and the downwards spiral of related events that followed: ‘I experienced severe financial difficulty as a result of the Gulf War. I didn’t fit into the correct brackets for Government assistance. As a result, I have since lost my fiancée, my house and furniture. I am currently living in a B &B and have done so since returning from the Gulf.’ (Male Reservist volunteer, junior other rank CMT) By 18 months post war, comments were received from 12 HPVs who had required formal counsel. Of these, 7 HPVs’ problematic situations appeared to be related directly to the war, but this relationship was less clear in the remaining 5 comments. Of the war-related problems, similar health descriptions to those reported in the 7-12 months post war were reported most likely because 11 of the 12 HPVs were the same participants as at 12 months post war.: ‘Colds, tiredness, depression - I feel there must be a connection with the War.’ (Female Reservist called up, junior officer nurse). Some HPVs’ combined health problems with difficulties in their social relationships: ‘Disillusioned with previous employers. They dismiss my opinions stating that I have post- traumatic stress disorder. I’ve started using various alternative therapies to combat my feelings of stress, e.g. aromatherapy, relaxation tapes etc.’ (Male Reservist volunteer, junior other rank nurse) ‘Very unhappy and confused - marital problems - related to the War.’ (Male Reservist called up, senior other rank physiotherapist). Of the remaining 5 HPVs, one had continuing bereavement problems, and 4 raised problems arising at work but were unsure if these were directly related to the War.

The quality of sleep

Twenty-six HPVs (84%) contributed comments to the main theme of quality of sleep as for during deployment. Most related this to being under real or threatened attack. Some claimed as a consequence to have developed a state of hypervigilance that continued into post-war life. Others blamed the unfamiliar shift work undertaken in the war, but interestingly none blamed the long working hours. This comment given for deployment aptly captures all of these disruptive and seemingly lasting cumulative effects: “Disturbed sleep patterns, plus SCUD attacks every night caused excessive tiredness, until shifts cut back - then only generally tired. Greater increase of alertness and awareness to a point when any siren (police style) plus excessive tiredness prompted reflex actions. Duration of effects until long after return home”. (Female TA volunteer, senior officer nurse) In a few of the other deployment comments, lack of and disturbed sleep were perceived in terms of the stress outcomes some HPVs experienced: ‘Extreme tiredness and not feeling rested. Concentration was difficult after a while’ (Female Reservist called up, junior officer nurse) ‘After the 12 hr shift every-day period, we slept for long periods but even these periods were interrupted due to SCUD alerts, so sometimes a slight depressive state ensued and at times tempers became a little frayed’. (Male Reservist volunteered, junior other rank nurse) In other comments, the deployment work patterns were seen as a source not only of tiredness but also of isolating the HPVs one from another, due to being on different shifts: ‘They [work patterns] can lead to tiredness and lack of social contact - others were asleep when I came off and not awake when I left.’ (Female TA volunteer, senior officer nurse, field facility) Finally this comment relates exhaustion to the environmental and climatic conditions of life under war conditions in the Middle East and again, the outcome was one of isolation: ‘Too much travelling to and from work. Heat very exhausting. Very dusty causing chestiness. Also in cellars, dark and depressing. Felt very isolated’. (Male TA volunteer, junior other rank CMT, support facility)

The quality of sleep was categorised as being better, the same, or worse - than that before the War and was requested for each of the post-war time phases, 75% HPVs said that, in comparison to before the War, their sleep was the same, 22 (23%) said that it was worse, and 2 (2%) said that it was better than before the War. The 24 HPVs with changes (better or worse) in their sleep quality from before the War, were asked to comment as to why it had changed. Of those with worse sleep, 11 (50%) gave comments indicating that they were 'more easily aroused'; 5 (23%) indicated that they felt 'anxious’' and it was 'difficult to get off to sleep', 3 said that they had 'vivid dreams that disturbed their sleep', and 3 made similar comments to this one: ‘Let people sleep/rest whenever possible. Avoid making people do menial tasks just for the sake of.’ (Female TA volunteer, junior officer nurse) Both of the HPVs with better sleep said that they felt 'less stressed than before the War'. but did not explain why. These data, although indicative of change in one-quarter of the HPVs from before to after the War and in the main , of a problematic nature, suggest that the HPVs associated the changes in post war sleep to be related to some extent to their experience of the War and living in a war-zone.

Discussion

Although the above variables may seem diverse, their outcomes when adverse and experienced cumulatively can have a powerful effect upon the bio-psychosocial being of a person. In addition to the 'hassles' expressed in this article, other powerful and concurrent 'hassles' feature in several published articles based upon this study (see Table 2) leading to the view that there was no shortage of them to plague the military in and after the GW and irrespective of whether a combatant or a non-combatant. On the contrary, it seems logical to believe that they promoted stress in those who may at that time already have been vulnerable or were susceptible to becoming vulnerable. Zimbardo et al. [24] have defined stress as an individual’s response to external circumstances: ‘...the pattern of specific and non-specific responses an organism makes to stimulus events that disturbs its equilibrium and taxes or exceeds its ability to cope’. In contrast, Folkman (1984) conceives stress as an outcome that is onerous and detrimental to wellbeing arising from self-appraisal of a relationship between the environment and the individual [25]. Common life stressors are those associated with occupational overload (including emotional exhaustion, de-personalization and diminished personal accomplishment) [26], and exposure to major life events [27] including those that are catastrophic [28]. Physiological stress reactions are internal, predictable and spontaneous. For example, the GW soldier who is described as being frozen to the spot during a SCUD attack with the inability to don IPE clothing as a protection against chemical contamination, reminds us that extreme fear can immobilize a person to the point when he or she cannot function [29]. Physiological changes such as short-phase stress responses include increased respiration, blood pressure and heart rate; sharpened cognition; blunting of pain and altered intestinal action. Prolonged exposure to stressors can lead to stress responses that include muscular tension, sleep disturbance, eating disorders, withdrawal, and release of stress hormones and suppression of these can lead to the adoption of health damaging behaviors [30]. Psychological stress and physiological stress have both been found to contribute to adverse health in animals under laboratory conditions [31,32]. Short and longer-term physical and psychological stress responses arising from war-related stressors that lie outside of a person’s normal experience, have collectively been termed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) [33]. This can have an acute onset or be delayed by months or years after a traumatic event and become a chronic persistent syndrome.

Despite the 'hassles' effect on some HPVs, the majority of them did not overtly admit to stress or illness in the post war time-phases, in fact some were very positive in their approach to life throughout. Several authors suggest that good survival is dependent upon the individual's personal resources (coping mechanisms) to counter stress effects [34,35]. Furthermore, the concept of ‘hardiness’ is also beneficial with its elements of control, commitment and challenge. However, in some aspects of the data , Reservists do seem to have found life harder than those in the TA in the GW and this was not without reasoned cause as they had more than their share, fair or otherwise, of additional 'hassles' (they perceived their pre-deployment training as poor or bad; they did not feel as well prepared as other military groups; some had no role on arrival in the Gulf; others felt they were marginalized at embarkation, and all were excluded from national celebrations). Furthermore, it is likely that living in the community as civilians, they would have had less military bonding and contact with military networks in which to share their experiences by way of de-stress than those in the TA or Regulars.

Limitations

The outcomes of many British GW studies have been based upon data collected not months but many years after the war’s end. Such lengthy delays have been recognized as raising the possibility of increasing error in participants’ recall [36,37]. As with many studies that seek to explore, describe and explain unforeseen life events (and including aspects of warfare), the ideal of representative samples and controls before, during and after such events was neither feasible nor realistic for the present study. It is acknowledged that the non-random sample selection could have caused bias but it is believed that the efforts to ‘engineer’ the same-subject sample with participant representation in the key military dimensions of military category (Reserve/ VS), deployment category (called up/ volunteer) and GW occupation (nurses/ CMTS/ other health professionals), go some way towards lessening this potential effect. It can also be suggested that the study’s reliability is strengthened by the high ‘acceptance to participate’ of the HPVs (71%) and the high HPV participation retention level (90.5%) across the 18 months of the duration of the study.

Conclusion

This article has sought to place the impact of some of the HPVs’ experiences of the war within time-phases that extended from before to up to 18 months after the war’ s end. By doing so it has been possible to see more clearly and within context, the HPVs’ reactions as non-combatants to matters of morality (e.g. the justness of the war), or principle (referral to formal counsellors), or deprivation (lack of sleep), as well as ascertaining differences between the groups within the participant sample. Not expected to be a conventional war at outset by the Allied Command, the spectre of chemical contamination loomed equally large for both HPVs and combatants alike, creating a shared atmosphere of intense fear. Reservists appeared to be less resilient to adversity than those in the TA whose training was up to date but both groups suffered from inter military group disharmony as their most difficult stressor. From the findings, it can be suggested that health workers should inquiry about a patient’s service history of ‘hassles’ in order to exercise insight into their potential effects.

References

- Norwood AE, Ursano RJ (1996) The Gulf War. Ursano RJ and Norwood AE (Eds.), The emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War Veterans family’s communities and nations Washington DC, USA American Psychiatric Press Inc p. 3-21.

- Dunning CM (1996) From citizen to soldier: Mobilization of Reservists. Ursano RJ and Norwood AE (Eds.), Emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War Veterans family’s communities and nations Washington DC, USA American Psychiatric Press Inc pp. 197-226.

- Wright KM, Marlowe DH, Gifford RK (1996) Deployment stress and Operation Desert Shield: preparation for the War. Ursano RJ Norwood AE (Eds.), Emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War Veterans families, communities and nations. Washington DC, USA American Psychiatric Press Inc pp. 283-314.

- Gifford RK, Ursano JR, Stuart JA, Engel CC (2006) Stress and stressors of the early phases of the Persian Gulf War. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B Biological Sciences 361(1468): 85-91.

- Muir K (1992) Arms and the woman. London, UK Sinclair Stevenson.

- de la Billiere P (1992) Storm Command: A personal account of the Gulf War. London Harper Collins Publishers.

- Mc Manners H (1993) The scars of war. Harper Collins Publishers, London, UK.

- Jones E, Hodgins Vermaas R, McCartney H, Everitt B, Beech C (2002) Post combat syndromes from the Boer War to the Gulf War: a cluster analysis of their nature and attribution. British Medical Journal 324(7333): 321- 324.

- Dandeker C, Greenberg N, Orme (2011) The UK’s Reserve Forces: Retrospect and Prospect. Armed Forces and Society. Sage Publications Online 37(2): 341-360.

- Iverson AC Greenberg N (2009) Advances in psychiatric treatment. Royal Psychiatrics 15(3): 100-106.

- Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer AD, Lazarus RS (1981) Comparison of two modes of20stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events.” Journal of behavioral medicine 4(1): 1-39.

- Bouteyre E, Maurel M, Bernaud J (2009) Daily hassles and depressive symptoms among first year psychology students in France: the role of coping and social support. Stress and Health 23(2):93-99.

- Creswell W (2003) Research design: qualitative and mixed methods approach. Sage Publications Folkman S (Eds.), Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 46(4): 839-352.

- Lee HA, Gabriel R, Bolton PJ, BaleA J, Jackson M (2002) Health status and clinical diagnoses of 3000 UK Gulf War veterans. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 95(10): 491-497.

- Krippendorff K (2004) Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Newbury Park and London, UK Sage pp. 272-273.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual Res Psych 3(2): 77-101.

- Merrill J, Williams A (1995) Benefice respect for autonomy and justice: principles in practice. Nurse Researcher 3(1): 24-32.

- Wild D, Fulton E (2019) British Non-Regular Services Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of Pre-Deployment Military Advice for The Gulf War. Research & Reviews Health Care Open Access J 3(2).

- Wild D. (2020) British non-regular Services health professional veterans' perceptions of their social relationships, social support and sharing Gulf War (1991) Experiences in the 18 Months Post-War. Current Trends in Biostatistics & Biometrics 2(3).

- Wild D. (2018) UK Gulf War Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of and Recommendations for Pre Deployment Training: The Past Informing an Uncertain Future?. Research & Reviews, Health Care Open Access Journal 2(2).

- Wild D. (2019) Recall of Casualty Care During the Gulf War (1991) by British Non-regular Services Health Professional COJ Nurse Healthcare. 5(2).

- Wild D. (2020) Ninety-Five British Gulf War Health Professionals’ Met and Unmet Expectations of Re-Entry to Civilian Life Following Military Deployment. Current Trends in Biostatistics & Biometrics 1(5).

- Wild D. (2020) Civilian and part-time Services health care professionals' reactions to military roles during deployment to the Gulf War (1991) (in Press)

- Zimbardo P, McDermott M, Jansz J, Metaal N (1995) Psychology a European text. London, UK Harper Collins Publisher pp. 412-426

- Folkman S (1984) Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 46(4): 839-852.

- Maslach C, Florian V (1988) Burnout job setting and self-evaluation amongst rehabilitation counsellors. Rehabilitation Psychology 33(2): 135-157.

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH (1967) The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 11(2): 213-218.

- Raphael B (1986) When disaster strikes. A handbook for caring professions Hutchinson, London, UK.

- O'Brien LS, Payne RG (1993) Prevention and management of panic in personnel facing a chemical threat - lessons from the Gulf War. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 139(2): 41-45.

- Chrousos GP, Gold PW (1992) The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioural homeostasis. Journal of the American Medical Association 267(9): 1244-1252.

- Ader R, Cohen N (1993) Psychoneuroimmunology: Conditioning and stress. Annual Review of Psychology 44: 53-85.

- McEwan BS, Stellar E (1993) Stress and the individual, Mechanisms leading to disease. Archive of Internal Medicine 153(18): 2093-2101.

- Raphael B, Middleton W (1988) After the horror. British Medical Journal: Clinical Research Edition 296(6630): 1142-1144.

- Kobasa SC, Maddi SR, Kahn S (1982) Hardiness and health: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 42(1): 168-177.

- Wiebe D J (1991) Hardiness and stress modification: A test of proposed mechanisms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60(1): 89-99.

- Wessley S, Unwin C, Hotopf M, Hull L, Ismail K, et al. (2003) Stability of recall of military hazards over time: evidence from the Persian Gulf War of 1991. British Journal of Psychiatry 183(4): 314-322.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...