Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6679

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6679)

British Non-Regular Services Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of Pre-Deployment Military Advice for The Gulf War Volume 3 - Issue 2

Deidre wild1* and Emmie Fulton2

- 1Senior Research Fellow (Hon), Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Coventry University, Coventry, England

- 2Behavioural Interventions Research, Coventry University, Coventry, England

Received: December 08, 2018; Published: January 10, 2019

Corresponding author: Deidre wild, Senior Research Fellow (Hon). Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Coventry University, Coventry, England

DOI: 10.32474/RRHOAJ.2019.03.000156

Abstract

Little has been written about the receipt of advice and its perceived usefulness, or even if it was routinely provided by the British military to Voluntary and Reserve (non-Regular) Services troops in preparation for deployment to the Gulf War. The study in its entirety comprised data from three postal questionnaires (each six months apart) completed by 95 veterans commencing six months after their return home. Their perceptions of the usefulness of two forms of advice were explored] for domestic preparations (e.g. wills and insurance) and ii] for managing social relationships (close relationships and other military personnel) during pre- deployment to the Gulf War 1991. They also provided recommendations as to how such advice could be improved. Advice for domestic preparations (completion of wills and insurance, etc.) was received by 56% of the participants, but advice for managing social relationships with family and other military personnel once mobilised was sparse (8:8%) and in the main, was provided by charities. This last form of advice was perceived by most of the non-recipient veterans as being of a low priority for the military even though most of the veterans indicated qualitatively that it would have been useful. The veterans’ recommendations are discussed.

Keywords: Gulf War (1991); Voluntary Services Health Professional Veterans; Military Advice; Pre-Deployment

Introduction

The Mobilisation of British Voluntary Services and Reserve Health Personnel

In November 1990, the `British Government recognised that there was an insufficient number of Regular Services medical personnel to meet the projected casualties from the impending war with Iraq, commonly known as the Gulf War (GW). Part- time Territorial Army (TA) and equivalent Voluntary Services’ (VS) personnel working in health professional roles (doctors, nurses, and other professions allied to medicine) were invited to volunteer [1]. As the initial response proved to be inadequate, retired ex Regular Services health professional personnel whose names had been retained by the military on the Reserve List were compulsorily called up: an action not undertaken since the Korean War (1950-53). Several United States (US) authors [2,3] report that for US Reservists, pre-deployment to the GW proved to be an unusually short time in which to make domestic preparations; wind-up civilian work-life; mobilise into new military groups and receive training specific to the requirements of deployment to a war in the Middle East. Some US Reservists were reported as being dissatisfied and distressed because they had not anticipated either their call-up or their stressful transition from ‘civilian to soldier’ [3]. These reactions could well have been similar for the British health professional veterans (HPVs) who like their US Reservist counterparts, lived and worked in civilian communities and not in military establishments [4,5]. Those in the part-time TA received support from their community-based parent TA Units but the ex- Regular Reservists both called up and volunteers, often had not retained military connections. In effect and despite being on the Reserve List, they were no longer part of the ‘military family’ [6].

The importance of giving support to military families prior to and during British and other nations’ military separations in peace and war has been emphasised by many authors prior to the GW, as a means of avoiding disruption to the psychological wellbeing of service personnel during deployment [7-10]. Early evidence of such support for British families during the GW was found only in one small British study by Quinault (1992) in which 12 wives of RAF deployed personnel described their military support as adequate but found that as with US military families [11], a lack of accurate information-giving increased their levels of stress [12]. There appears to be a paucity of early research concerned with the reactions of British non-regular Services health professional troops towards the GW’s unique conventional and expected unconventional (chemical/biological) warfare context and circumstances. In its place, it seems that there has been a reliance upon the outcomes of the more extensive early US GW research [13,14] to fill the British experiential gaps with the assumption that socially, organisationally and culturally, US troops were ‘like with like’ in relation to their British counterparts. Therefore, despite the time lapse since data collection and this article, it is believed that this study and its findings remain relevant. In response to the paucity of literature, this part of the study incorporated 4 questions:

a) What advice was received by the HPVs from the military?

b) In what form was it received?

c) How effective was it according to the perceptions of the HPVs?

d) What recommendations do the HPVs suggest that could improve advice during pre-deployment.

Methodology

Design

The study utilised a longitudinal design comprising an initial postal questionnaire survey and two follow up postal questionnaires, each issued six months apart. The first questionnaire sought retrospective experiential data comprising reactions to warrelated (pre-deployment and deployment) circumstances; advice; health; social support, and social and professional relationships in the six months before and in the first six months following the return home. The second and third questionnaires requested the provision of prospective repeated data at 12 months and at 18 months post war in the above key areas of interest where change could be anticipated.

Recruitment of the Participant Sample

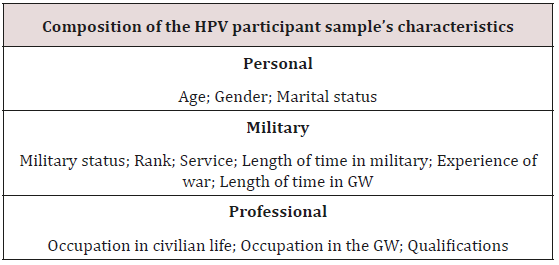

Recruitment was conducted between July and August 1991 some 4-5 months after the non-regular Services’ troops return home from the GW. The first of three stages of the recruitment of the non-regular Service troops as study’s participants was initially opportunistic. One HPV Reserve called-up nurse (a colleague known to the lead author) held a personal contact list of 74 HPVs who had returned home together by air in late March 1991 following the end of the GW. As it would have been unethical for the researcher to have had direct access to the contact list, the colleague acted as an intermediary by forwarding a letter from the author to those named with details of the study and a pre-paid postal return envelope for the return of completed contact details and consent form. In the event, 57 (47 ex regular Reservists and 10 Territorial Army personnel) of the 74 HPVs agreed to participate in the study: a return rate of 77%. In the second recruitment stage, a purposeful increase of the VS TA group to match the size of the Stage 1 recruited Reservists (n=47) and in similar health professional roles was sought. This was achieved by asking the 10 consenting VS TA participants from Stage 1, to act as ‘intermediaries’ in making a ‘snowball’ access to similar others within their own or other TA units. To facilitate this, each of them was supplied with 5 introductory letters (n=50) with pre-paid return contact slips for direct return to the author. As a result, a further 33 TA HPVs agreed to participate in the study raising the total for the VS TA to 43. Although there was no way of knowing if the total number of letters (n=50) had been issued by the initial TA HPV participants, the estimated percentage (assuming all letters had been issued) for recruitment in this stage was 66%. Finally, in a third recruitment stage, a GW veteran Welfare Officer in the Order of St John of Jerusalem (a voluntary service that provides welfare support to the army) having heard of the study, made direct contact with the author to seek inclusion for the 10 Welfare Officers (WOs) who had been volunteers in the GW. Using the same return system as in previous stages, 5 (50%) of these veterans agreed to become participants. Personal, professional and military demographic characteristic variables (as independent variables) of the participant sample of 95 HPVs are given in Table 1.

Procedure

First a pilot study with 5 participant HPVs assisted the researcher through focus groups and interviews in the preparation of the first questionnaire that included the receipt and acceptability of advice from the military during pre-deployment. Each of the three questionnaires, issued at 6 monthly intervals, comprised closed questions followed by related free text justification. This dual approach provided opportunity for a greater depth of understanding more so than either could have achieved if employed alone [15]. The pilot study’s HPVs identified two forms of pre-deployment advice that they claimed to have received from the military:

a) advice for domestic preparations, e.g. wills, life insurance, work and domestic financial affairs, and

b) advice for managing social relationships at home and in the military.

These form the focus of this article and coupled with demographic data given in Table 1, enabled the analysis of advice to be seen from personal, civilian and military perspectives.

Variables of Interest and Data Analysis

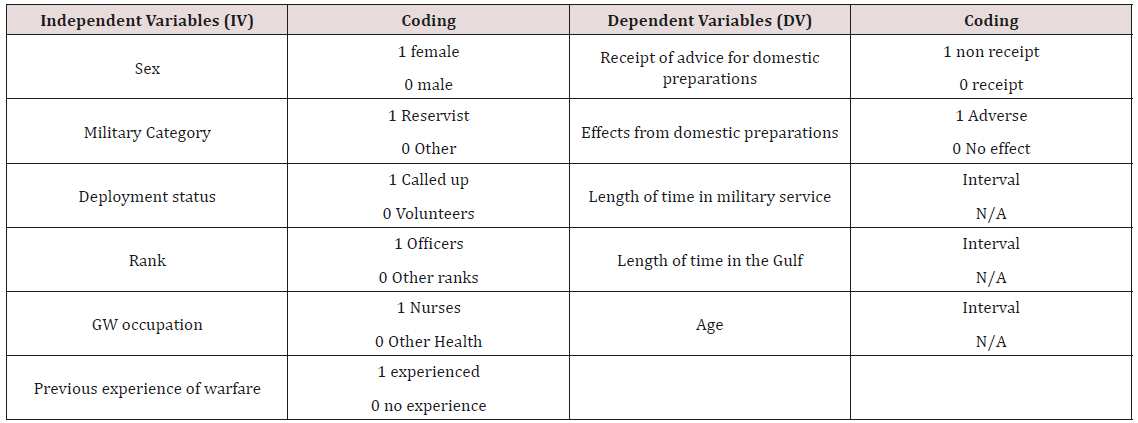

In 1993, the data were first analysed and then re-analysed in 2012 when presented as part of a successful PhD thesis. Quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 20. Logistic regression was employed to establish the relationship between a categorical dependent variable (DV) with one or more of the above characteristic independent variables (IV). It calculates the likelihood (ratio of the odds) of an event occurring or not. Table 2 provides the two types of variables and their values of interest (given as 1). Qualitative data were examined by two researchers independently identifying and categorising the key words or phrase labels using Thematic Analysis [16]. The labels were devised to capture as closely as possible the meaning of the HPVs’ original words or phrases [16,17]. Where there were differences of interpretation between the researchers, a joint reanalysis of the data was made to facilitate consensus.

Ethical Considerations

Although the study preceded the introduction of formal National ethical standards and procedures for British research, the general principles of: doing no harm; seeking participant informed consent; the acceptance of participant autonomy over compliance, and of respect for rights to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality [18] were upheld throughout the research process. Authoritative military and academic advice were taken before and throughout the study to avoid sensitive issues. All information forwarded to the HPVs cautioned them against breaching the Official Secrets Act. The data have been held securely and in accordance with the Data Protection Act, 1987 and its update in 1998. All data has been stored anonymously in digital format on a password-protected computer.

Results

Return Rate

A total of 134 contact letters were issued across the three recruitment stages resulting in 95 consenting HPVs and provided an estimated minimum overall response rate of 71%. It is of note that at the time of recruitment to the study, the total numbers of volunteer TA and Reserve personnel deployed to the GW had not been reported in the public domain but figures given some years after the GW suggest that the 95 HPVs in the participant sample represent a subset of some 9% of the total Reserve and TA (or similar VS organisations) health professional personnel sent to the GW [19].

Characteristics of the Participant Sample

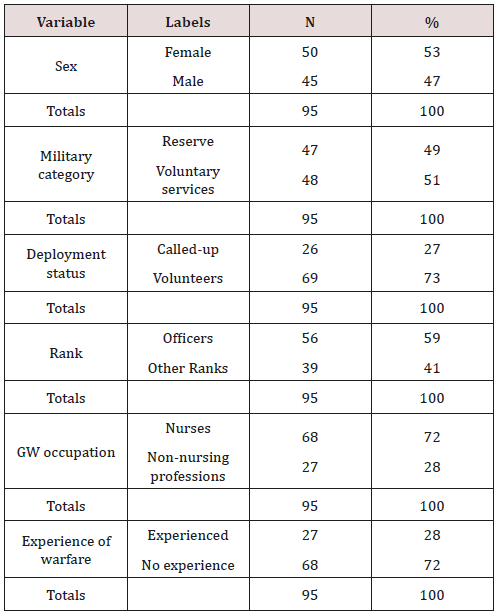

The personal, military and health professional details of the participants were collected. As shown in Table 3, there were 6% more females than males and the HPVs’ ages ranged from 23 to 53 years (mean=37; SD=8.59; median=35). Of the 48 in the Voluntary Services, all save the 5 Welfare Officers were in the Territorial Army [TA] and all were volunteers, whereas of the 47 in the Reserve, 26 (27%) were mandatorily called-up and the remaining 21 (21%) were volunteers. There were 18% more officers than those in other ranks. Sixty-eight (72%) of the HPVs were in nursing roles during the GW as compared with 27 (28%) in other health professions. Of the 95 HPVs, 27 (28%) had past warfare experience and of these, 17 (18%) were ex Regular Reservists and 10 (10%) were in the TA. The remaining 68 (72%) had no experience of warfare. Sixtyseven of the 68 nurses provided their civilian nursing qualifications (1 missing) and during the GW, 49 (73%) worked as Registered General Nurses; 4 (6%) as Registered Mental Nurses, and the remaining 14 (21%) were State Enrolled Nurses. All other health professionals (doctors, physiotherapists, etc.) were allocated to the same professional roles in the military as they held in civilian life. Only combat medical technicians (akin to civilian ambulance paramedics) worked in non-health civilian roles prior to the GW. The time spent in the Gulf for most HPVs was between 2 and 3 months. When the HPVs’ length of time in the Gulf was compared with their deployment military status using a Mann-Whitney U test, Reservists spent less time in deployment (mean rank=37.16) than those in the VS (mean rank = 58.61): a significant difference (U=618.500, Z= -2.414, p<0.01).

Types of Advice

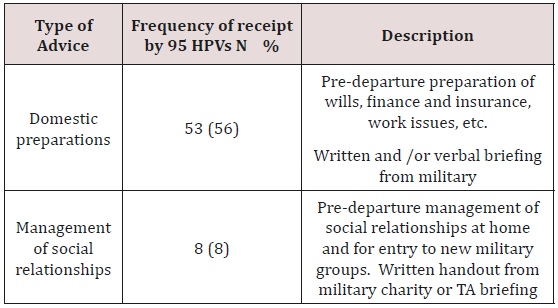

Table 4: Types of advice suggested in the Pilot Study as issued by the British military during pre-deployment (N=95).

The Pilot Study participants identified two forms of advice given by the military and/ or by related charities during pre-deployment to the GW with their respective frequencies of receipt by the 95 HPV participants, as shown in Table 4. ‘Advice for domestic preparations was the most frequently received form of advice (56%), whereas the receipt of advice regarding social relationships was considerably lower (8%). Both forms of advice were given in a written format and in the case of those in the TA, also in verbal briefings.

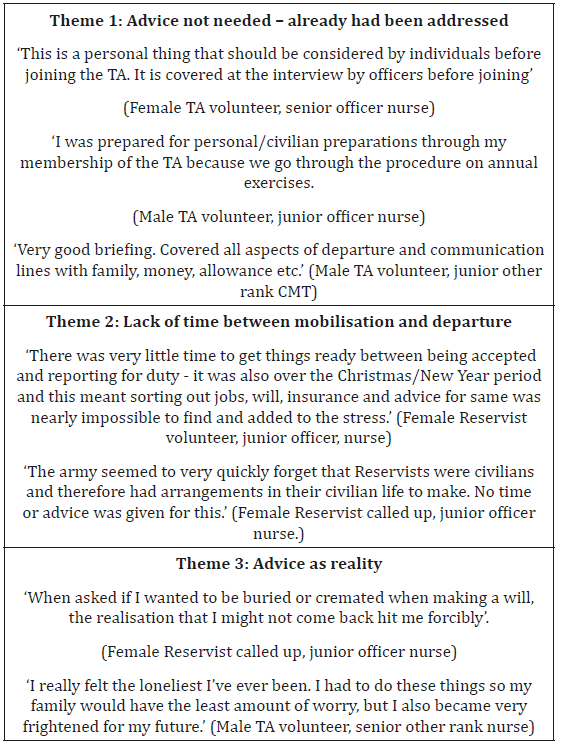

Frequency of Receipt of Advice for Pre-Deployment Domestic Preparations

Fifty-three of the 95 HPVs (56%) received advice from the military regarding their domestic preparations. Eight HPVs provided related descriptive comments and of these, five were in the TA. As shown in Table 5, Theme 1, those in the TA confidently recounted that their domestic affairs had already been adequately prepared as a routine annual requirement for all members of the part-time VS military and as such did not seem to need the advice. Of the remaining 42 (44%) participants who did not receive this form of advice, 33 provided written comments hypothesising on the effect such advice might have had if it had been received. Comments from the 33 non-recipients of advice for domestic preparations are given as Themes 2 and 3 in Table 5. In theme 2, some HPVs associated their non-receipt of advice with not having enough time between mobilisation and departure to the Gulf in which to access or put advice into practical use. It is also suggested that the timing of such preparations (during the run-up to Christmas 1990) had a negative effect upon their stress levels even before departure to the Gulf as they tried to juggle home commitments with military requirements. Furthermore, some Reservists called-up emphasised that they had civilian responsibilities that required additional attention (e.g. rearranging care for dependent relatives, arranging work cover if self-employed) but the military were perceived as making little or no allowances for these issues. As indicated in the last comments in Table 5, the making of wills raised the HPVs’ consciousness of the gravity of their situation and its potential for life-threat (injury or death). This was likely to have been particularly difficult for Reservists call-up, who had no choice in having to place their lives at risk.

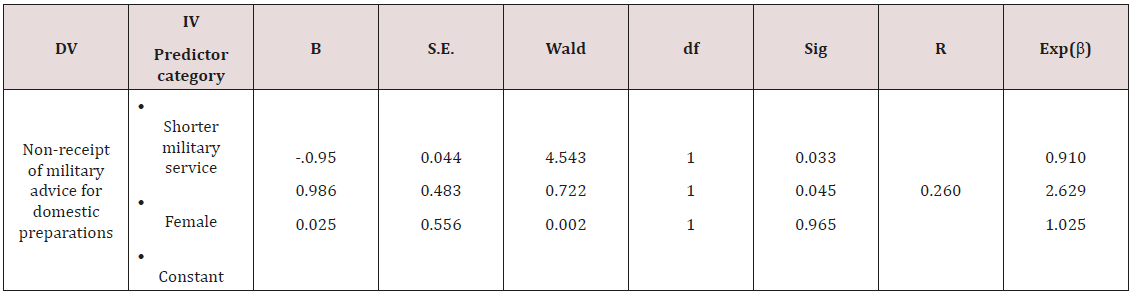

Predicting the likelihood of Non-Receipt of Military Advice for Domestic Preparations

Table 6: Logistic regression to predict the likelihood of non-receipt of military advice for domestic preparations with sample characteristics (N=95).

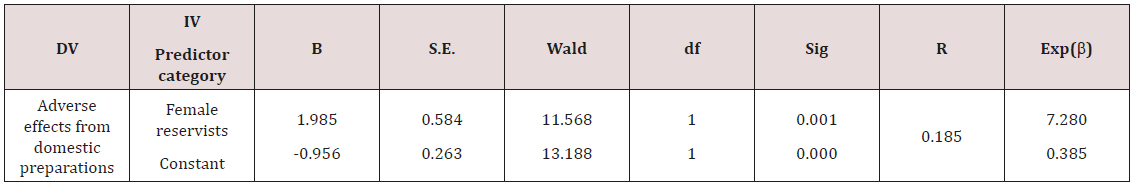

Using logistic regression as shown in Table 6, ‘time in military service’ (shorter time) and gender (females) were the best predictors of the ‘non-receipt of advice’. When both variables were re-entered into the Logistic regression model as the interaction term ‘gender/time in the military’, the output was not significant. Thus, those who were female and those with a shorter length of military service each had a significant and independent likelihood of being the non-recipients of advice (shorter military service R=0.260, β=0-910, p=0.033; female R=0.260, β=0.0986, p=0.045). When the 95 HPVs were asked to indicate if they had experienced any effects (practical or psychological) from undertaking domestic preparations, 34 (36%) HPVs described experiencing ‘adverse’ effects and 57 (60%) stated that they had ‘no effects’. The remaining 4 (4%) HPVs perceived these effects as ‘positive’ indicating a sense of relief at having made adequate provision for themselves and their families (in some cases, will-making was a task that had been put off in the past). Of those with adverse effects, a majority (28:82%) provided written comments indicating that making their wills heightened a morbid anticipatory fear about going to war. As shown in Table 7, using logistic regression to predict those most likely to have adverse effects from domestic preparations, a significant interaction between gender and military status indicated that female reservists were those most likely to have adverse effects (R=0.185, β=7-280, p=0.001). Using chi-square, no significant relationship was found between those in receipt of advice for domestic preparations with those with adverse effects arising from undertaking such preparations (χ2 =0.33, df=1, p>0.05).

Table 7: Logistic regression to predict the likelihood or not of effects from domestic preparations in sample characteristics (N=91).

*4 values excluded

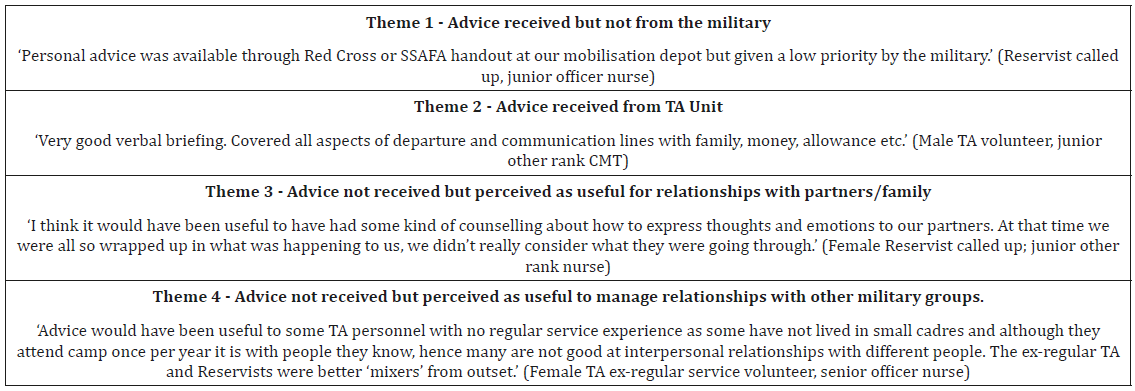

Receipt of Pre-deployment Military Advice Regarding the Management of Social Relationships

Four TA respondents commented that they had received good advice from their TA Unit in the form of a ‘briefing’ for the management of their social relationships prior to departure to the Gulf. A further 4 Reservists stated that they had been recipients of handouts from military charities such as Soldiers, Sailors, Air Force Association (SSAFA) but had received nothing directly from the military. The remaining 87 (92%) stated that this type off advice had not been received. Thirty-two HPVs provided related comments. Of these, 8 had received advice and 24 were from non-recipients, who speculated upon the potential usefulness of such advice had they received it. Examples drawn from both sets of comments are given below in Table 8 under thematic headings. Thematic analysis of the 24 non-recipient HPVs’ comments given in Table 8 revealed that all participants believed hypothetically that if they had received advice on how to manage their social relationships, it could have been beneficial. Those with close partners (Theme 3) suggested that such advice could have lessened their tendency towards selfcentredness and withdrawal which caused spousal resentment and upset with other family members prior to departure. Other HPVs hypothesised that the receipt of this advice could have been beneficial in their coping with the relationship difficulties that arose when joining new military groups both during pre-deployment training and following arrival in the Gulf (Theme 4).

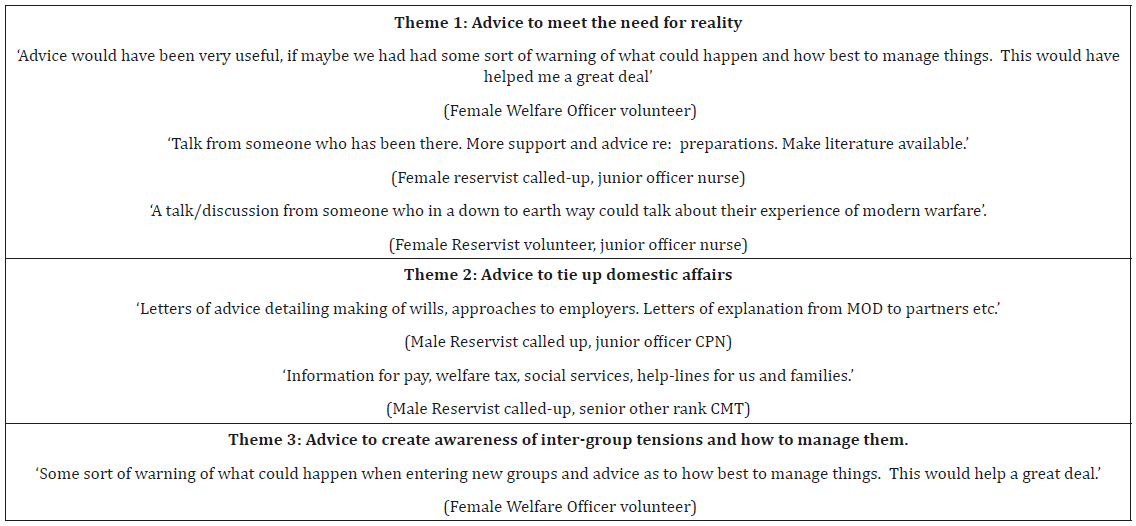

HPVs’ Recommendations to Improve Advice During Pre-deployment

Ninety-seven recommendations were given by 81 (85%) of the 95 HPVs, regarding improvements to all aspects of the experience of pre-deployment to war. Of these, the most frequently suggested recommendation by 48 (59%) of the 81 HPVs) was to improve advice for domestic preparations. Of these, three themes were formed as given in Table 9. In theme 1, some HPVs recommended that they should be pre-warned regarding the reality of the war that lay ahead as part of their preparations and most wanted this to be delivered by an experienced war veteran. Others (theme 2) wanted written information listing the practical domestic requirements to be met before departure as described above but they also included a direct military contact via letter to partners explaining why the non-regular health professionals had been requested to volunteer or had been called up. The final theme addressed the psychosocial issue of entry to new groups and recommended being forewarned of the likelihood of inter-group difficulties and how to manage these. The remaining 14 (15%) said that ‘no improvements were necessary’.

Discussion

The study aimed to describe the frequency of receipt of the two forms of advice received during pre- deployment by the HPVs, how they were accessed and their perceived quality and usefulness. The small number of VS TA recipients of pre-deployment advice for domestic preparations accessed it through their units with delivery from personnel with experience of participation in previous wars. As such, there appears to have been dissemination of verbal and written advice concerning these TA preparations. From the comments, the TA HPVs appear to have had their domestic preparations well in hand as a requirement for their military routine preparations for annual exercises. As they appeared to regard their upkeep as a personal responsibility rather than a pressure from the military, this might suggest that they had adopted a problem-focussed coping strategy towards domestic preparations rather than the emotion-focussed coping strategy apparent in the comments from some Reservists. Meredith [20] contend that by adopting the first approach, it is likely that the sense of internal control and resilience to stress could increase [21]. The above findings are akin to other published findings from this study showing that the TA HPVs were more satisfied with their pre-deployment training for the GW than their Reservist counterparts [22].

The non-receipt of pre-deployment advice for domestic preparations was associated independently with the HPVs who were female and those with a shorter military service. One tentative explanation for this gender effect could lie in the observed unequal distribution in civilian life in the undertaking of housework workload where the greater share is more likely to be undertaken by females rather than males [23]. Conversely males tend to attend to matters of family finances. These factors, coupled with the additional family pressures associated with the festive season at the end of 1990, may have led a significant number of females to become overwhelmed by the enormity of juggling personal, family and military tasks in the short pre-deployment time. Females were the most likely non-recipients of advice for their domestic affairs, but female Reservists were those most likely to have reported adverse stress effects from undertaking them. The latter took the form of anticipatory morbid thoughts of death and injury when making wills or taking out new or additional insurance. It seems plausible that the lack of adverse effects from domestic preparations in VS TA females could have been influenced by their close alignment with males through shared military training and roles; mutual commitment to the TA’s organisational requirements, and their self-confidence in having relatively unproblematic and in-place preparations. Additionally, Wood [24] suggest that females can learn male dominance behaviours through shared training, which in turn can lead to greater gender equality [24].

In this study, those with a shorter military service were more likely to have had less advice for domestic preparations than those with a longer service. This is not dissimilar to the findings of McCubbin [25] who found that younger service personnel (i.e., by default, those who are the most likely to have a shorter military service experience) were those who tended to avoid formal and informal advice. Case [26] in reviewing the knowledge-base for people’s assessment of threat report that the uptake of information is determined by the nature of the stressor, the would-be recipient’s appreciation of the effectiveness of responses to the threat (response efficacy), and their beliefs about their own ability to carry out effective responses (self-efficacy) [26]. Thus, it seems that HPVs with shorter service time could have had less anticipatory understanding about warfare; less recourse to war-related advice, and less belief that such advice could make a difference to their actions. For them, advice could have seemed irrelevant. In a study of US females deployed to the more recent Iraq and Afghanistan wars, Carter-Visscher [27] reported that females perceived themselves as having a lower level of preparedness for deployment and exhibited greater pre-deployment concerns about family than males [27]. These findings re-echo some of the present study’s gender findings, despite differences in sampling, military structures and cultures.

Pincus [28] notes that as the military person becomes more involved with military preparations for deployment so too is there a gradual withdrawal from family up to the date of departure [28]. Although the importance of the provision of military support to families prior to and during the time of military separation has been emphasised by many authors before the GW [7-10], there is little evidence of any prioritisation for the issue of British military advice for managing social relationships before departure to the GW. Less than ten per cent of the HPVs received advice for the management of their social relationships prior to departure (even though the pilot study respondents raised it as an available form of military advice). However, had it been received, the non-recipient HPVs believed that the pre-departure strain on family relationships, arising all be it understandably from the HPVs’ self-confessed war-focused attitudes since call-up, could have been eased. Others hypothesised that had it been received, it could have reduced the inter-personal tensions reported in other parts of this study concerned with the HPVs’ entry into new military groups during pre-deployment and later during deployment. The paucity of such advice could be of relevance to other published data from this study whereby it has been suggested that the HPVs’ lack of stress management training from the military during pre-deployment [22] showed a tendency towards avoidance by the military of issues that were perceived to be of ‘psychosocial’ origins.

It is not possible from these data to quantify whether the receipt or not of either form of advice is related to: its availability from the military; the ability and desire of the individual to access it; the receptiveness of the individual’s open or closed mind towards its content; avoidance or denial of its context, or anticipation of its relevance to a given situation [29]. For these, further research with the close co-operation of the military would be necessary. Certainly, as the receipt or not by the HPVs of advice for domestic preparations was not significantly associated with its effects, this could suggest that even when there was receipt of this form of advice, it did not appear to act as a stress moderator, as previously reported in a study of the receipt of health care advice [30]. Furthermore, in comparative research by Sharpley [31], no evidence was found that military pre-deployment stress briefings reduced psychological stress [31]. It could be argued that advice for social relationships from any source was so low that it is impossible to determine its therapeutic value, but the HPVs’ recommendations were clear that more effort should be made by the military to target audiences where there is likely to be the most need; and that the form of the advice (content, presentation), and logistics (its timing) are tailored to meet the reality of their needs.

Limitations

The study in its entirety is believed to be one of the earliest of the British GW studies and although some 28 years have passed since the War’s end and the study’s data collections began, interest in the GW and its unique circumstances (including the unresolved illness in some veteran troops) has not waned. Indeed, unlike this study, many British Gulf War studies have been based upon data collected not months but many years after the GW. Such lengthy delays have been recognised as raising the possibility of increasing error in participants’ recall [32,33]. As with many studies that seek to explore, describe and explain unforeseen life events (and including aspects of warfare), the ideal of representative samples and controls before, during and after such events [34] was neither feasible nor realistic for the present study. It is acknowledged that the non-random sample selection could have caused bias but it is believed that the efforts to ‘engineer’ the same-subject sample with participant representation in the key military dimensions of military category (Reserve/ VS), deployment category (called up/ volunteer) and GW occupation (nurses/ CMTS/ other health professionals), go some way towards lessening this potential effect. It can also be suggested that the study’s reliability is strengthened by the high ‘acceptance to participate’ of the HPVs (71%) and the high HPV participation retention level (90.5%) across the 18 months of the duration of the study.

Conclusions

Although those in the TA were comparatively well organised for the GW due to their annual domestic preparations for military exercises, this was not the case for some of the female Reservists who qualitatively showed morbid stress responses to their preparations. Overall females and those with a shorter military service were the least likely to have received this form of advice. Advice for the management of social relationships with families and with new military groups during the pre-deployment phase did not appear to have been recognised by the military as areas where advice could be useful. In contrast, veterans were clear in their recommendations as to how future need for advice for these social relationship’s difficulties could be met. We suggest that listening to the voices of those who have experienced warfare can better support the development of advice with relevant content and an efficacious mode of delivery in the future. By doing so, some of the stress of pre-deployment could be reduced.

References

- De la Billiere P (1992) Storm Command: A personal account of the Gulf War. Harper Collins Publishers, London pp. 118.

- Peebles-Kleiger, MJ, Kleiger JH (1994) Re-integration stress for Desert Storm families: Wartime deployments and family trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress 7(2):173-194.

- Dunning CM (1996) From citizen to soldier: Mobilisation of Reservists (1996). In: Ursano RJ, Norwood AE (Eds.) Emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War. Veterans, families, communities and nations. American Psychiatric Press, Inc, Washington DC, USA, pp. 197-226.

- Huebner A, Mancini J (2005) Adjustments among Adolescents in Military Families when a parent is Deployed. Final report to the military Family Research Institute and Department of Defense Quality of Life Office., Military Family Research Institute, Lafayette, Indiana. Purdue University.

- Lemmon KM, Chartrand JM (2005) Caring for America’s children: Military youth in the time of war. Paediatics in Review 30(6): 42-48.

- Dandeker C, Greenberg N, Orme G (2011) The UK’s Reserve Forces: Retrospect and Prospect. Armed Forces and Society 37(2).

- Hill R (1949) Families under stress: Adjustment to the crises of war separation and reunion. New York: Harper, pp. 443.

- Wallis CG (1968) Stress in service families. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 61(10): 976-978.

- Wawman JR (1968) The changing military environment. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 61(10): 979-982.

- Hamilton S (1986) Supporting Service Families: A report on the main problems facing spouses of Australian Defence Force personnel and some recommended solutions. Australian Department of Defence Publication.

- Figley CR (1993) Coping with the stressors on the home front. (Psychological research on the Persian Gulf War). Journal of Social Issues 49(4): 51-71.

- Quinault W (1992) Problems among the dependants of RAF personnel during the Gulf War. Nursing Practice 5(2):12-23.

- Gifford RK, Marlowe D, Wright KM, Bartone PT, Martin JA ., Wright, K.M., Bartione, P. t...... and Martin, J.a. (1992) Unit cohesion in Operations Desert Shield/Storm unit cohesion I Operations Desert Shield/ Storm. The Journal of the US Army Medical Department 11/12: 11-13.

- Perconte ST, Wilson AT, Pontius EB, Dietrick AL, Spiro KJ (1993) Psychological and war stress symptoms among deployed and nondeployed reservists following the Persian Gulf War. Military Medicine 158(8): 516-521.

- Creswell W (2003) Research design: qualitative and mixed methods approaches. 2nd (edn). Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, New Delhi, USA.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual Res Psych 3(2): 77-101.

- Krippendorff K (2004) Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage, Newbury Park and London: 272-273.

- Merrill J, Williams A (1995) Benefice, respect for autonomy and justice: principles in practice. Nurse Researcher 3(1): 24-34.

- Lee HA, Gabriel R, Bolton PJ, Bale A J, Jackson M (2002) Health status and clinical diagnoses of 3000 UK Gulf War veterans. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 95(10):491-497.

- Vogt, DS, Pless AP, King LA, King DW (2005) Deployment stressors, gender, and mental health outcomes among Gulf War I veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress 18(3): 272-284.

- Meredith LS, Sherbourne CD, Gail S, Hansell L, Ritschard HV, et al. (2011) Promoting Psychological Resilience in the U.S. Military. Rand Corporation.

- Wild D (2018) UK Gulf War Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of and Recommendations for Pre-Deployment Training: The Past Informing an Uncertain Future?. Research and Reviews. Health Care Open Access Journal 2(2).

- Bianci SM, Milkie MA, Sayer LC, Robinson JP (2000) Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces 79(1): 191-228.

- Wood W, Christensen PN, Hebl R, Rotherber H. (1997) Conformity to sex-typed norms, affect, and the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73(3): 523-535.

- McCubbin HI, Dahl BB, Lester GR, Benson D, Robertson ML (1976) Coping repertoires of families adapting to prolonged war-induced separations. Journal of Marriage and the Family 38(3): 461-471.

- Case DO, Andrews JE, Johnson JD, Allard SL (2005) Avoiding versus seeking: the relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Librarians Association 93(3): 353-362.

- Carter Visscher R, Polusny MA, Murdoch P, Thuras P, Erbes CR, et al. (2010) Predeployment gender differences in stressors and mental health among U.S. National Guard troops poised for Operation Iraqi Freedom deployment. Journal of Trauma Stress 23(1): 78-85.

- Pincus SH, House R, Christensen J, Adler LE (2001) The emotional cycle of deployment: A military family perspective. Journal of the Army Medical Department 2(5): 15-23.

- Wilson TD (1999) Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation 5(3): 249-270.

- Miller SM, Managan CE (1983) Interesting effects of information and coping style in adapting to gynaecological stress: should a doctor tell all? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45(1): 223-236.

- Sharpely JG, Fear T, Greenberg N, Jones M, Wessley S (2007) Pre- operational stress briefing in the military: does it have any effect? Occupational Medicine Advance.

- Wessley S, Unwin C, Hotopf M, Hull L, Ismail K, et al. (2003) Stability of recall of military hazards over time: evidence from the Persian Gulf War of 1991. British Journal of Psychiatry 183(4): 314-322.

- King DW, King LA, Gudanoowski D, Vreven DL (1995) Alternative representations of war zone stressors relationships to posttraumatic stress disorder in male and female Vietnam veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 104(1):184-195.

- Parker RM (1993) Threats to the validity of research. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 36(3): 131-138.

.png)