Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1381

Research Article(ISSN: 2644-1381)

British Non-Regular Services Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of their Social Relationships, Support and Sharing of Gulf War (1991) Experiences in the 18 Months Post-War Volume 2 - Issue 3

Deidre Wild*

- Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Coventry, UK

Received: February 19, 2020; Published: March 02, 2020

*Corresponding author: Deidre Wild, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Coventry, Coventry UK

DOI: 10.32474/CTBB.2020.02.000138

Abstract

Using data collected in 1991 and recently re-analysed, this article describes and compares 95 British Voluntary Services and Reserve health professional veterans’ (HPVs) perceptions of their social relationships, their uptake of formal and informal support (including advice), and the need to talk about their Gulf War (1991) experiences in the 18 months after their return home. The study design comprised three six monthly postal questionnaire surveys issued over eighteen months post-war. Qualitative and quantitative data were gathered in each survey. As the 95 participant veterans made the transition from soldier to civilian, at 12 months post-war there was a peak in their receipt of formal and informal social support, and a concurrent marked increase in difficult social relationships from the first questionnaire’s findings. Other war-experienced veterans were the preferred post war donors of support and to a lesser extent family members. Social sharing was prevalent in the first six months post war but the veterans found it increasingly difficult to talk about their experiences even though they wanted to across the remaining postwar periods. In effect by the end of the study, three spheres of some veterans’ sense of social wellbeing were compromised with those at home, at work, and in their wider social life.

Keywords: Gulf War; British; health professional veterans; social relationships, support and sharing

Abbreviations: HPVs: health professional veterans; GW: Gulf War; VS: Voluntary Services; TA: Territorial Army

Background

Social support has been defined as a human activity with either the presence or absence of psychosocial support from significant others [1].Types of social support have been described as: emotional (promotes self-esteem/ empathy, affection), informational (provides useful information), tangible (giving of material or practical aid) [2] and appraisal (self-evaluation of support) [3]. It has been conceptualized also as a system with a range of social networks [4]. The presence of social support does not necessarily mean that social interaction has taken place [5]. Furthermore, the effects of personal interaction can be beneficial or harmful to the recipient of support [6,7].This is dependent upon the extent to which support is appropriate to the recipient’s circumstances and irrespective of whether it is perceived by the recipient or donor as helpful at the time of delivery [7]. Studies that focus upon the recipient’s reactions to support and the way that donor support is offered suggest that if this is negatively framed, the recipient can become susceptible to low self-esteem, inferiority, passivity, or submission [8,9]. This in turn may influence the recipient’s perception of the usefulness or not of the support given [9]. Evidence suggests that social support moderates the psychological impact that follows adverse life events[1,6,10], while other research outcomes conclude that social support plays an important part in acting against the effects of stressors [3,4,11] and in improving recovery from ill health [12]. The quality and availability of inter-personal relationships have been identified as affecting the immune system’s responses [13]. Furthermore, a lack of social support has been associated with an increased likelihood of ill health and mortality [2,12,14].Some authors have found that having supportive social networks tend to reduce distress in individuals when under stress, but the converse was found for those with unsupportive or critical social relationships [15-18]. Reviews of social support research [1,11] conclude that seeking to establish a relationship between health and social support is often undermined by methodological inadequacies including the formulation of concepts and measurements. Dakof and Taylor (1990) studied helpful and unhelpful support in terms of it being present or absent in the perceptions of 55 patients with a life-threatening disease [4]. Emotional support from intimate others was identified as the most helpful type of support, whereas informational support and tangible aid were the least helpful. However, they draw attention to the complexity and diversity of the types and effects of social support uncovered in their study. This led them to conclude that measuring social support as a sole concept is limited unless the specific behaviors of the recipient and donor are also recognized [4]. Despite methodological challenges arising from situational complexity, in a study with a randomly selected sample of 254 adults in US society, adaptive personality characteristics and positive family support was reported as having acted directly or indirectly in maintaining psychological health by reducing depression arising from other normally occurring life events [14]. In a family study of deployed military, younger service personnel were found to be less aware of the availability of informal and formal military support [19]. Rime (1995) adds to the complexity of support by describing two thought processes that could arise in an individual after an emotional experience [20]. In the first, mental rumination is given as the process of conscious thinking about the event over an extended period of time, and the second is the social sharing of the experience in which the person openly communicates the experience to others [20]. However, his conclusion from a series of controlled studies was that when rehearsal (mental rumination) of a past emotional episode was extended over a long period, this was associated with a poorer emotional recovery. Positive outcomes from studies of social sharing (talking or writing about traumatic events) are given by several authors and include improved health [21,22] and immunological function [23]. Some of these authors further suggest that not confronting trauma leaves it unresolved and although writing about trauma (as opposed to talking about it) can cause more initial distress, it allows a person time to think through the meaning of trauma and possible solutions for themselves [23]. Finally, Pennebaker and Harber [24] undertook a study of collective talking and thinking about the GW with a cohort of Dallas residents during and after the GW. They found that during the event talking and thinking about it was high as a means of collective social support for about two weeks. This was followed by a six-week period of inhibition, where talking declined but thinking about it continued. Then a final phase of adaptation occurred where the respondents neither talked nor thought about the event.

Methodology

Design

Using a predominately prospective longitudinal design comprising three postal questionnaire surveys, each 6 months apart, the data included in this article were collected in the first questionnaire issued some six months after the War’s end. A small pilot study to refine the materials and agree the content preceded the main study. The transcripts from the pilot study suggested that the seeking of social support should be a separate variable from the need to talk about the war as the respondents appeared to describe each in different terms.

Materials

The questionnaire contained a series of related closed and open questions. This ‘mix’ of quantitative and qualitative data enabled a greater depth of understanding of the HPVs’ experiences than either method when employed alone [25].

Sample recruitment procedure

A GW nurse veteran known to the author acted as an intermediary by contacting (she held the addresses) and informing 73 veterans (who returned home from the GW with her in one cohort) about the study. From this, the first 57 HPVs (47 Reservists and 10 Territorial Army [TA] personnel) consented to receive questionnaires. The first TA participants facilitated the addition of a further 33 TA GW volunteers to join the study via a snowball system of contact with similar others they had served with in the Gulf. Finally, five Welfare Officers from the Order of St John of Jerusalem joined the study having heard of it via a press release.Thus, the final sample comprised 47 Reservists (26 called-up and 21 volunteers); 43 volunteer TA, and 5 volunteer Welfare Officers.

Mode of Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and logistic regression with a forward stepwise Wald was used as the main predictive test. Qualitative data in the form of the HPVs’ comments were examined first by two researchers independently identifying and categorizing key words or phrases. The phrase labels produced were devised to capture as closely as possible the meaning of the HPVs’ original words or phrases. This thematic analysis has been described by several authors [26,27]. The two researchers then made cross comparisons (and when necessary re-examined the data) to reach consensus. In some instances, the qualitative data were transformed into new variables to permit the use of descriptive statistics.

Ethical considerations

Although the principles adhered to early in 1991 preceded the formal ethical requirements for today’s research, the general principles of doing no harm; securing informed consent; the acceptance of autonomy over compliance, and respect for rights to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality [28] was upheld throughout the research. Authoritative military and academic advice were taken throughout the study to avoid potentially sensitive issues in the materials. All information forwarded to the HPVs cautioned them against breaching the Official Secrets Act. The data were ¬held securely and in accordance with the Data Protection Act, 1987 and its update in 1998.

Key questions and variables of interest for this article:

1. What proportion of HPVs experienced war-related and

unrelated difficult relationships from before the war to 18

months post-war?

2. Who in the HPVs’ social network were identified as the

main sources of difficult relationships from before to 18 months

post-war?

3. What was the HPVs’ frequency pattern for informal and

formal support from during deployment to 18 months after the

GW and who did they identify as the most and least preferred

donors?

4. What was the frequency pattern for the HPVs’ social

sharing (by talking) about the GW across the post war time

phases and to what extent did those who had not shared, want

to do so?

Variables of interest and their values are given in (Table 1).

Results

Characteristics of the participant sample

The participant sample of 95 HPVs represented a range of health professions (nurses; doctors; combat technicians, physiotherapy, welfare officers and laboratory staff) and provided an estimated questionnaire return rate of 71%. The initial 95 HPV participant sample was reduced to 89 in the second time-phase and to 86 in the third and final time-phase. Personal, professional and military characteristic data were formatted mainly as dichotomous variables. Those relevant to the present inquiry are given in (Table 2). There were 6% more females than males and the HPVs’ ages ranged from 23 to 53 years (mean=37; SD=8.59; median=35).Of the 48 volunteers, all except the 5 Welfare Officers were in the TA whereas of the 47 ex Regular Reservists, 26 (27%) were mandatorily called-up and the remaining 21 (21%) were volunteers. There were 18% more officers than those in other ranks. Sixty-eight (72%) of the HPVs were in nursing roles during the GW as compared with 27 (28%) in other health professions. Of the 95 HPVs, 27 (28%) had past warfare experience and of these, 17 (18%) were ex Regular Reservists and 10 (10%) were in the TA. The remaining 68 (72%) had no experience of warfare. When the Figure 1- for the civilian occupations of the 95 HPVs were cross tabulated with their qualifications, 67 held nursing qualifications and of these, 49 (73%) worked as Registered General Nurses; 4 (6%) as Registered Mental Nurses, and the remaining 14 (21%) as State Enrolled Nurses. All health professionals worked in the same professional roles but across a much narrower range of specialisms in the GW than in their civilian work. Only combat medical technicians (akin to paramedics) worked in a variety of non-health civilian roles prior to the GW.

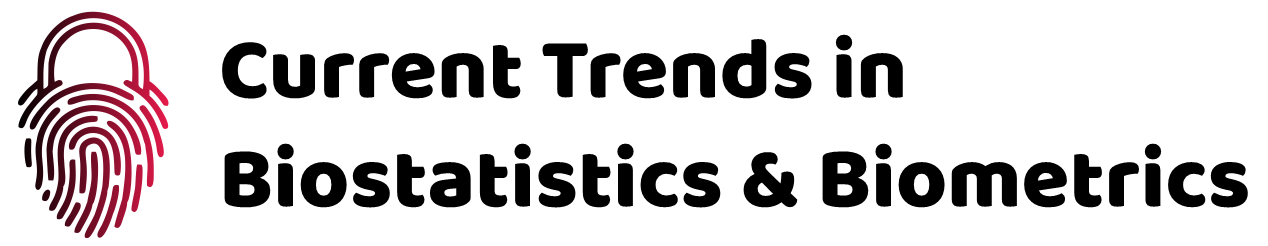

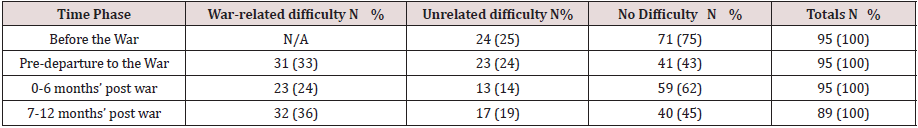

The HPVs’ social relationships from before the war to 18 months post war

As shown in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 1, war-related relationship difficulties were at higher levels in each time phase after the war than relationships difficulties unrelated to the war. In the first 6 months post-war phase, the HPVs’ percentage frequencies for war-related and unrelated difficult relationships both decreased from those given for pre-departure suggesting the probability of a ‘honeymoon effect’ of greater wellbeing following reunion [30]. The level of HPVs with difficult relationships unrelated to the war showed a small increase across the 7-12-month phase but at a level below that for pre-departure. This was followed by a further decrease in the 13-18 months to a level lower than at any time before the war. In contrast, the percentage frequencies for those who had war-related relationship difficulties showed a linear increase over the three post–war phases to levels that were higher than those recorded for unrelated difficult relationships in the same timeframe. These observations suggest that although some pre-war relationship difficulties unrelated to the war re-occurred during the first 6 months post-war phase, others were resolved over a longer time. In contrast, an increasing number of HPVs began to experience war-related relationship difficulties for the first time across the post-war time phases that had not been experienced before the war at pre-departure.

Table 3: HPVs with and without war-related and unrelated difficulty with social relationships from before to after the War.

Figure 1: Percentage changes over time in those with war-related and war-unrelated sources of difficulty from before the war to 18 months post-War.

Legend: Series 1: GW related difficulties Δ; Series 2: Unrelated

difficulties

Time-phases:

1 - Before the War.

2 - Pre-departure

3 - First 6 months post war

4 - 7-12 months post war

5 - 13-18 months post war

The HPVs with difficult relationships (GW-related and unrelated)

were asked to identify those in their social networks who

were the greatest sources of difficulty in each time phase. As shown

in (Table 4), in the 6 months before the war and at pre-departure to

the Gulf, parents were identified as the source of greatest difficulty,

but this declined over the post-war phases. Partners also were a

high source of difficulty before the war and in particular prior to

departure. However, unlike parents, there was a marked increase

in difficulty with partners during the first six months after the

War followed by a further increase across the 7-12 months’ phase

before a small decrease by 18 months post-war (most likely due to

the resolution of some with problems unrelated to the war). Both

of these post-war percentage frequencies for partners as sources of

difficulty were higher than those calculated for before the war. Of

the other family members, difficult relationships with children had

a low frequency for before the War and although this increased in

the aftermath phases, the number of children identified as ‘difficult’

remained small. Of the groups outside of close family, i.e. employers

and work colleagues, who were reported as having been more

supportive/ accepting than close adult family members at the time

of mobilization, both showed sharp percentage increases as sources

of difficulty in the 7-12 and 13-18 month time-phases. Furthermore,

although few in number, relationship difficulty with friends and

TA unit colleagues who had not gone to the GW emerged as a new

source of difficulty in the penultimate and final time-phases. It is

of note that by calculating the number of sources of relationship

difficulties per HPV it was possible to see that by these time phases

each HPV had more sources of difficult relationships than in the 0-6

months post-war.

Table 4: HPVs identification of sources of relationship difficulties from 6 months before to 18 months after the Gulf War.

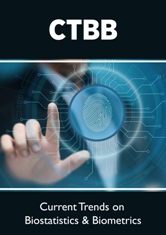

The uptake of formal and informal social support after the GW

In Table 5 the time phases’ frequencies for HPVs referred for formal counseling /support (provided by senior officers, clergy, nurses, or psychologists) are reported comparatively with those for informal support. As shown, formal counselling /support has a much lower level of uptake in comparison with seeking of informal support in each post-war time phase. The populations seeking formal counselling/ support were similar in the two later time phases (most were the same HPVs) but not when these were compared with those in first time phase where the population was largely different. The relative consistency of those seeking informal support could suggest a likelihood that many of the same HPVs sought informal support in more than one of the time-phases but this was not substantiated by crosstabulation. For, as shown in Table 4, just as the sources of relationship difficulties changed over time so too did the population of HPVs experiencing them.

Identification of the HPVs most likely to seek informal support across the three post-war time phases

Logistic regression was used to identify the best predictor for seeking informal support from the sample characteristics in each of the 3 post-war time phases. In the first 6 months postwar using the interaction term gender/military category, female Reservists had a greater likelihood than TA and VS females and males of seeking informal support during the 0-6 months postwar (B=2080, r=0.139, Exp(B)=5.208, p<0.001).No significant personal or military predictor was found for the 7-12 months post war(p>0.05) but in the 13-18 months post war females (but not specifically Reservist females) were identified as those most likely to seek informal support (B=1.884, r=0.169, Exp(B)=6.58, p<0.01).

The HPVs’ uptake of military advice and their identification of and preference for their post-war donors of informal support

Forty-five (47%) of the HPVs received advice (informative advice) for post-war adjustment between the war’s end and embarkation. Of these, 24 HPVs (53%) found the advice ‘wholly or partially helpful’ and 21 (47%) found it ‘unhelpful’. As shown in Comment Box 1, reasons for disaffection ranged from criticism of the timing of advice and its delivery to the appropriateness of content. In general, it was not taken seriously by either those delivering it or those receiving it. Several comments particularly from Reservists reflect these opinions including with hindsight, that had it been received in a more organized, consistent and timely way, it could have been beneficial. After the return home, other war veterans and to a lesser extent spouses/partners were qualitatively identified from the HPVs open responses as those most likely to be the preferred donors of informal support, as given ‘as given in comment Box 2. The HPVs appeared to be more critical of partners, parents and friends. For, although willing to listen, they were not always perceived by the HPVs as being able to respond with the depth of understanding that the HPVs felt that they needed. Some HPVs recognized that it was difficult to articulate their feelings even when there was the availability of close family willing to listen. In contrast, other HPVs claimed to find an ease of shared understanding with those in the military who had had similar war-related experiences and often these communications were described as not being dependent upon what was said. In Comment Box 2, a range of comments are presented to illustrate some of the communication problems experienced by the HPVs following their re-entry into civilian life at home up to 18 months post-war with close family, friends, in the workplace with former colleagues, and with those in the TA Units who did not volunteer for duty in the war.

Social sharing by talking about war experiences

As shown in Table 6 and illustrated in Figure 2, the majority of

HPVs had talked about the war in all of the post-war time-phases.

Those who had not needed to talk had their lowest percentage

level in the 0-6 months post-war and their highest percentage

level in the 7-12 months post-war, whereas for those who had not

talked but wanted to, the converse was found. By 13-18 months

post war, there was a drop to the lowest percentage level for those

who had talked about the war which qualitatively suggested that

the HPVs were beginning to withdraw from those in their social

network. At the same time, there is their awareness that they had

not talked to anyone in depth about the war despite wanting to, but

their inhibition was perceived as due to the fault of others rather

than themselves. This situation is illustrated in the two following

comments given for the 13-18 months pre-war:

a. ‘No-one is interested - no-one is receptive.’(Male Reservist

called up, junior other rank nurse. Survey for 13-18 months

post war).

b. ‘I feel the need but have not found anyone to talk to that

really wants to listen - fully.’ (Female Reservist called up, junior

officer nurse. Survey for 13-18 months post war)

Figure 2: Percentages of the HPVs with and without verbal social sharing across the post war time phases.

Legend: Series 1 - Had not talked about the War but wanted to. ¨.

Series 2 - Had no need to talk about the War.

Series 3 - Had talked about the War.

Time phases: 1 - First 6 months post-war. 2 - 7-12 months post war.

3 - 13-18 months post-war.

Discussion

Despite evidence of a ‘honeymoon’ effect in the first 6 months post war [30], the pre-departure level of war-related relationship difficulties did not diminish in the longer term of this study but continued to increase. Although parents were identified as the greatest source of relationship difficulty before departure this was not the case after the war where increased relationship difficulty was observed primarily with partners. In the seeking of informal support for post war adjustment problems, the HPVs showed a preference for GW and other war experienced veterans as donors and to a lesser extent spouses/partners, similar to the findings of other studies [29-31]. Having good social support has been associated with moderating the impact of traumatic effects [1,4,7,29,32]. Conversely, several authors contend that where social support is absent or inadequate, this can induce adverse effects upon mental and physical health [14]. The HPVs’ qualitative evidence indicates that after the first six months post war, a gradual distancing from partners/spouses took place most likely due to an inability to communicate satisfactorily about war-related experiences, as in veterans of other wars [29,30,32,33]. Even when spouses/partners were involved in providing social support, some HPVs reported that meaningful interaction did not taken place [6,29]. It can be hypothesized that the above preference for veteran donors’ support could have created or added to difficulty in relationships with spouses/partners, if this excluded them from undertaking a supportive role. Increased social isolation and decreased social support could suggest the potential for some of these HPVs to have stress-related illness. In this, the 7-12 months seems to be a crucial point in time for the emergence of adjustment problems. This could be because concurrently the HPVs had their highest level of close (spouse/partners) relationships difficulties and in the seeking of formal and informal social support. Although the percentage of HPVs who talked about the War decreased towards the end of the study, at this same time almost one quarter of the HPVs who had not done so, still wanted to talk about the war. The relatively low levels of formal support across the postwar timeframe of 18 months suggests that the HPVs who were experiencing adjustment problems did not appear to recognize or consider that this could be of benefit. This may be because, as with some aspects of pre-deployment advice [34], military advice given at the time of embarkation and designed to alert the HPVs to the potential for post-war adjustment problems, was not taken seriously or found to be useful by most of those in receipt of it.

The present quantitative and qualitative findings show that after the first 6 months post-war, the HPVs’ self-evaluation and communication with those close to them (partners/spouses) became more difficult with increased time from the war. Although there is evidence of resolution of some difficulties within their close relationships (particularly difficulties unrelated to the war), by the end of the study, war-related difficulty with friends, work colleagues and with TA personnel who did not volunteer for the war increased in the same timeframe.That HPVs disappointed with homecoming were more likely to experience difficult relationships in each post-war time-phase, could add further substance to the concept that the negative quality of reunion on return home can have subsequent detrimental effects upon a veteran’s social network of relationships [35]. Females Reservists were found to be more likely to seek social support than females in the TA and males in general in the 0-6 months post-war. This finding is not surprising as following the return to the UK, Reservists were geographically scattered after demobilization with no parent military unit for support or indeed close proximity with other GW veterans. From being part of the ‘military family’ suddenly they were back where they started as civilians but with little time to adjust to civilian life. The friends made under the testing circumstances of the war were scattered often without time to say goodbye [35].This was not the experience of female (and male) TA, who were welcomed back to their units and praised by the media and society, but this largely excluded Reservists [35].

In the 7-12 months post war, although the seeking of informal support and talking about the war reached their respective peaks and difficulty with social relationships had escalated from the preceding time-phase, no significant personal or military characteristic indicator for informal social support was found. In the 13-18 months post-war, females were significantly more likely to seek support than males (as was also found for deployment). Reasons for this could lie in past studies that show that females are more likely than males to respond emotionally to adverse threatening stressors [36] and to perceive their psychological responses in more negative terms. It is also suggested that females place a stronger value on interpersonal relationships [37] and report more distress than males [38].

Limitations

The major limitation was the opportunistic selection of the participant HPVs. This was unavoidable due to the constraints of finance, distance and security (no access available to either a representative military sample or suitably selected controls.). However, although generalization cannot be an intended outcome, the mixed method approach is believed to have maximized understanding of these particular HPVs’ responses and increased the trustworthiness of the findings. Unravelling the complexity of social support and all of its different mechanisms lay beyond the scope of this study, as was the recommended measurement of individual HPV’s’ resources of personal hardiness, personality type, and other individual factors. No claim is made that the contribution of the present findings adds greatly to the psychosocial theory of social support. Rather it is intended to contribute to a pragmatic complex social history of the experiences of this particular group of HPVs as casualty carers in a modern war.

Conclusion

Supporting troops during and after war is a much-discussed topic for the military and society in general. The data presented aims to give insight into the HPVs’ experience of social support and their preferences for those who gave it. The pattern of warrelated relationship difficulties with close spouses/partners, longstanding friends, colleagues at work and TA colleagues who did not volunteer for GW duty, presents a rollercoaster of difficulties with different members of the HPVs’ social network across the life span of the study. By its end, some HPVs were showing signs of becoming isolated and an increased number of them had not talked about the war even though they wanted to do so (as opposed to not needing to talk). Formal counselling support was at a low level throughout the post-war time span and one reason for this could be because the HPVs did not have sufficient insight into their adjustment problems to know that they needed professional formal help. Alternatively, it could be that for some veterans’ families “taking the horse to water does not necessarily mean it will drink”. Thus, the real challenge for veterans would seem to be accessing a type of support that increases the confidence and knowledge of veterans (and that includes their significant others) so that they can recognize and address their own adjustment problems and develop healing strategies with support but not undue pressure from others.

References

- ThoitsPA (1982) Conceptual methodological and theoreticalproblems in studying social support as a buffer against life stress. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 23(2): 145-159.

- Kaplan BH, Cassel JC (1977) Social support and health. Medical Care 15(5): 47-58.

- Berkman LF, Syme L (1979) Social networks host resistance and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology 109(2): 186-204.

- Dakof GA, Taylor SE, (1990) Victims’ perceptions of social support: What is helpful from whom. Journal of Personality and Social Support 58(1): 80-89.

- Cohen S (1988) Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology 7(3): 269-297.

- Eaton L (1993) Misfortunes of war. Nursing Times 89(30): 16-17.

- Gottlieb B H (1983) Social support as a focus for integrative research in psychology. American Psychologist 38(3): 278-287.

- Shinn M, Lehmann S, Wong NW (1984) Social interaction and social support. Journal of Social Issues 40(4), 55-76.

- Brickman P, Rabinowitz VC, Coates D, Cohn E, Kidder L (1982) Models of helping and coping. American Psychologist 37(4):364-384.

- Fisher JD, Nadler A, WitcherAlagna S (1982) Recipient reactions to aid. Psychological Bulletin 91(1): 27-54.

- DunkelSchetter C, Folkman S, Lazarus RS (1987) Correlates of social support receipt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53(1): 71-80.

- Kuklic JA, Mahler HIM(1989) Social support and recovery from surgery. Health Psychology8(2): 221-238.

- Kennedy S, KiecoltGlaser JK, Glaser R (1988) Immunological consequences of acute and chronic stressors: Mediating role of interpersonal relationships. British Journal of Medical Psychology 61(1): 77-85.

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH (1991) Life stressors personal and social resources and depression: A 4-yesr structural model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 100(1): 31-38.

- Rook KS (1984) The negative side of social interaction: Impact on psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 46(5): 1097-1108.

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D (1988) Social relationships and health. Science 241(4865): 540-545.

- Lepore SJ (1992) Social conflict social support and psychological distress: Evidence of cross-domain buffering effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63(5): 857-867.

- Vinokur AD, van Ryn M (1993) Social support and undermining in close relationships: Their independent effects on the mental health of unemployed persons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65(2): 350-359.

- McCubbin HI, Dahl BB, Lester GR, Benson D, Robertson ML (1976) Coping repertoires of families adapting to prolonged war-induced separations. Journal of Marriage and the Family38(3): 461-471.

- Rime B (1995) Mental rumination, social sharing, and the recovery from emotional exposure. In J W Pennebaker (Ed.) Emotion disclosure and health. Washington DC: American Psychological Association 271-292.

- Schatzow E Herman JL (1989) Breaking secrecy: Adult survivors disclose to their families. Psychiatric Clinis of North America 12(2): 337-349.

- Pennebaker JW, Beall SK(1986) Confronting a traumatic event: Towards an understanding of inhibition and disease. Journal of Abnormal Psychology95(3): 274-281.

- Pennebaker JW, KiecoltGlaser JK, Glaser R (1988) Disclosure of traumas and immune function: Implications for psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology 56(2): 239-245.

- Pennebaker JW, Harber K (1993) A social stage model of collective coping: The Loma Prieta earthquake and the Persian Gulf War. Journal of Social Issues 49(4): 125-145.

- Kaplan B, Duchon D(1988) Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in information systems research: A case study. Management Information Systems Quarterly 12(4): 571-586.

- Krippendorff K (2004) Content analysis : An introduction to its methodology.Newbury Park and London Sage 272-273.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual Res Psych 23(2): 77-101.

- Merrell J, Williams A (1995) Benefice respect for autonomy and justice: principles in practice. Nurse Researcher 3(1): 24-32.

- Borus FB(1973) Reentry: adjustment issues facing the Vietnam returnee. Archives of General Psychiatry 28(4):501-506.

- Yerkes SA, Holloway C(1996) War and homecomings: the stressors of war and of returning from war. In Ursano Norwood AE (eds) Emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War Veterans families communities and nationsWashington DC American Psychiatric Press Inc pp.25-42.

- Greenberg N, Langston V, Scott R (2006) How to TRiM Away at Post Traumatic Stress Reactions: Traumatic Risk Management Now and in the Future. In Human Dimensions in Military Operations Military Leaders’ Strategies for Addressing Stress and Psychological Support35-(1): 35-36.

- Raphael B (1986) When disaster strikes A handbook for caring professions. London: Hutchinsonpp. 219.

- Hobfoll SE, Spielberger CD, Breznitz S, Figley C, Folkman S, (1991) Warrelated stress: Addressing the stress of war and other traumatic events. American Psychologist 46(8): 848-855.

- Wild D, Fulton E (2019) British NonRegular Services Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of PreDeployment Military Advice for The Gulf War. Research & Reviews Health Care Open Access J 3: 2.

- Wild D (2019) Ninety-Five British Gulf War Health Professionals’ Met and Unmet Expectations of Re-Entry to Civilian Life Following Military Deployment. Current Trends Biostatistics & Biometrics 1(5):117-125.

- BenZur H, Zeidner M (1991) Anxiety and bodily symptoms under threat of missile attack; The Israeli scene. Anxiety Research4(2): 79-95.

- Andrews B Brewin CRRose S (2003) Gender social support and PTSD in victims of violent crime. Journal of Traumatic Stress16(4): 421–427.

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE (1995) Sex differences in distress: Real or artifact?. American Sociological Review60(3): 449-468.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...