Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4676

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4676)

Causative Factors Affecting Livelihood Status of Cassava Producers in Kwara State of Nigeria Volume 6 - Issue 2

Sadiq MS1*, Singh IP2, Ahmad MM3, Lawal M4 and Kabeer YM1

- 1Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, FUD, Nigeria

- 2Department of Agricultural Economics, SKRAU, India

- 3Department of Agricultural Economics, BUK, Kano, Nigeria

- 4Department of Agricultural Education, Federal College of Education, Nigeria

Received: January 22, 2019; Published: January 30, 2019

Corresponding author: Sadiq Mohammed Sanusi, Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, FUD, Nigeria

DOI: 10.32474/CIACR.2019.06.000233

Abstract

Empirical analysis of poverty determinants is crucial in evolving strategies in ensuring no poverty and zero hunger among the smallholder cassava farmers who championed cassava food security in Nigeria. Thus, the present research determined the poverty status and the causative factors that affect livelihood status of cassava farmers in Kwara State of Nigeria using field survey information of 2018 production season (wet season) elicited via structured questionnaire complemented with interview schedule from 123 active cassava producers sampled through multi-stage sampling design. The collected data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The results showed a young farming population with the interest and zeal to invest in cassava production if given adequate support. However, almost half of the sampled population finds it difficult to keep the body and soul together as per capita daily income of N367.82 ($1.19) per household head to carter for farm family needs is below the threshold of $1.90 recommended by World Bank for per person per day. However, the major factors affecting the livelihood status of the cassava farmers were decline in labour productivity owing to old age, too many mouths of non-productivity dependents to contend with at household level, fatigue due to long farm distance which affects labour efficiency and medic expenditure due to ill-health of the farm family member which drain their capital investment. Therefore, the study recommends provision of social interventions which is crucial for risk management and building a resilient livelihood. In addition, there is a need for improvement on the social amenities and the gesture of health insurance scheme should be extended to the farmers so as to boost their moral towards striving to ensure cassava food security in the studied area and the country in general.

Keywords: Poverty status; Causal factors; Cassava farmers; Kwara State; Nigeria

Introduction

Sengul and Tuncer [1] defined poverty as a situation which prevents people from achieving an internationally acceptable level of well-being owing to the deprivation that encompasses shortfalls or inadequacies in basic human necessities. This situation, which is alluded to production failure owing to suppression of markets, institutional and distributional failure is characterized by disease, low life expectancy and physical and mental retardation [2,3]. Economic progress in developing countries since 1990s has led to an increase of more than 1.6 billion in the number of people living above the moderate poverty line. They include 750 million rural people who continue to live in rural areas-demonstrating that rural development has been and will continue to be essential to eradicating hunger and poverty [4]. People exiting low-productivity agriculture are moving mostly into low-productivity informal services, usually in urban areas. The report further showed that since 1990s, the rates of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa have changed very little, and the absolute number of poor has increased.

Poverty in Nigeria is pervasive although the country is rich in human and material resources that should translate into better living standards. In recent times, the need to attain the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) has necessitated the drive to eradicate extreme poverty in developing countries to become more urgent [5]. The significance of rural poverty is underscored by the fact that as much as 45 to 80% of the national populace in most developing countries in Africa resides in rural areas and largely dependent on agriculture for livelihood sustainability [2,6]. Instead of finding a pathway out of poverty, poor rural Africans who migrate to cities are more likely to join the already large numbers of urban poor. A similar dynamic is seen in South Asia, where the rural poor are more likely to escape poverty by remaining in rural areas than by moving to cities [4].

The viability of the value chain of cassava production which is the aim of government initiative on cassava production promotion and other donor agencies in collaboration with the government (e.g. IFAD) can only be sustained if the producers of the raw material in the value chain have a sustainable livelihood. Most of the studies conducted on cassava in the studied area explore mostly on the value addition and production with little or no effort to look at the viability of the farmers’ income to sustain them and keep their business afloat. It is in view of these that this research was conceptualized to provide policymakers with an insight into a framework for decision, which is needed to effectively minimize poverty and its monetary and non-monetary dimensions. Therefore, Kwara State was chosen as a pilot area given that it is a major cassava producing area in the ecological zone (Northcentral) which has the highest comparative advantage in cassava production in Nigeria.

In addition, empirical proof on the nature of poverty among the smallholder cassava farmers who are the powerhouse of the chain viz. the extent of influence of the source of income on agriculture and inequality in income is necessary for policy choices. Although, the predicted poverty minimization scenarios for smallholder farmers vary greatly depending upon the nature and rate of poverty-related policies as actual evidence suggests that the depth and severity are still at its worst in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [7,8]. Therefore, the present research aimed at determining the poverty status and the causative factors affecting the livelihood status of cassava farmers in Kwara State of Nigeria. The specific objectives were to describe the socio-economic characteristics of the producers in the studied area; to determine the poverty status of the producers in the studied area; and, to determine the causative factors affecting livelihood status of the cassava producers in the studied area.

Research Methodology

Kwara State of Nigeria lies between longitudes 40 20’ and 40 25’ East of the Greenwich meridian and latitudes 80 30’ and 80 50’ North of the equator. The population of the state is approximately 2.3 million and has a landmass of approximately 36,825 square kilometres with varying physical features like hills, lowland, rivers etc. Its vegetation is derived savannah with two distinct wet and dry seasons, with mean annual precipitation and monthly temperature of 1000-1500mm and 250C-340C, respectively [9]. The major occupation of the inhabitants is agricultural activities complemented by trade, artisanal, Ayurvedic medicine etc. The multi-stage sampling design was used to draw a sample size of 128 cassava farmers and the undated data elicited from the farmers through the administration of structured questionnaire complemented with interview schedule. In generating the sample size, Agricultural zone D was conveniently selected given that cassava crop adapts well in all the agricultural zones in the state and due to the cost and time constraints of the final year undergraduate research student. In the next stage, two Local Government Areas (LGAs), namely Offa and Oyun were purposively selected due to the preponderance of cassava producers. From each of the selected LGAs, four villages were randomly selected and from each of the selected villages, 16 farmers were randomly selected, thus given a total sample size of 128 farmers. However, only 123 retrieved questionnaires were found valid for analysis. Objectives 1, 2, and 3 were achieved using descriptive statistics; Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) poverty index; and, logarithm regression model (logit), respectively.

Empirical Model

OECD Equivalence Scale

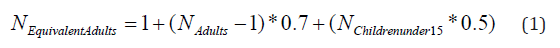

The OECD scale which takes into account both household size and composition was used to determine the adult equivalent and it is specified below (Anonymous, 2007):

The first adult is given a weight of 1.

The other adults are given a weight of 0.7, to reflect economies of scale.

Children are given a weight of 0.5 to reflect their presumably lower needs.

Construction of the Poverty Line

Poverty line has been defined as the minimum or the cutoff standard of per capita income below which an individual or household is described as poor [10]. According to Federal Office of Statistics (FOS) (2013), as reported by Sadiq and Kolo [10], there is no official poverty line in Nigeria and as such many earlier studies have used poverty lines which are proportions of the average per capita income. However, in this study per capita income which is considered more appropriate in past studies because it is consistent and does not change over a period of time when compared to expenditure was adopted. Therefore, the poverty line was defined as the two-thirds (2/3) of the mean value of per capita income in the study area. The farm households were categorized into the poor and non-poor group using the two-third mean per capita income as the benchmark [11]. Households whose mean per capita income falls below the poverty line are regarded as being poor while those with their income above the benchmark are non-poor. It is worth to note that when dealing with poverty, income should be used as the parameter for measurement and not consumption which is just one out of the two to three components of income as postulated by Keynes theory. The reason is that being food insecure (consumption) does not imply being poor as some people have misery instinct, but being poor implies being food insecure. However, when dealing with food security, expenditure should be used as the parameter for measurement and not income as income scope exceed consumption.

PCHMI = THMI / HHS (2)

MPCHMI = TPCHMI / TNR (3)

PL = 2 / 3*MPCHMI (4)

Where:

PCHI = Per Capita Household Monthly Income

THMI = Total Household Monthly Income

HHS = Household Size

MPCHMI = Mean Per Capita Households Monthly Income

TNR = Total Number of Respondent

TPCHMI = Total Per Capita Households Monthly Income

PL = Poverty Line

FGT Poverty Index

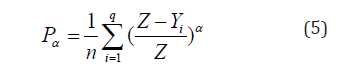

Following Sadiq and Kolo [10] the FGT poverty index developed by Foster et al. [12] was adopted to measure poverty status among cassava farmers in Kwara State of Nigeria. The FGT poverty index is given as:

Where:

P = Poverty index

n = Total number of households in the population

q = The number of poor households

z = The poverty line for the household

yi = Household income

α = Poverty aversion parameter and takes on value 0, 1, 2

(z-yi/z)a= Proportion shortfall in income below the poverty line

α takes on the value of 0,1,2 to determine the type of poverty index.

When α = 0 in FGT, the expression reduces to

p0=q/n (6)

This is called poverty incidence or gap, describing the proportion of the population that falls below the poverty line.

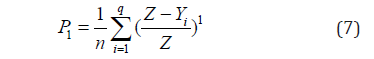

When α =1 in FGT, the expression reduces to

This is called the Poverty depth

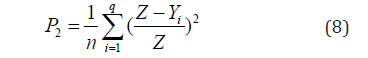

When α =2 in FGT, the expression becomes

This is called Poverty Severity Index. This index weighs the poverty of the poorest household more heavily than those just slightly below the poverty line. It adds to the poverty depth an element of unequal distribution of the poorest household’s income below the poverty line.

Logistic Regression Model

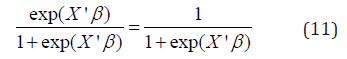

The logit model assumes:

An equivalent form can be stated as:

This can be expressed as

And re-written as

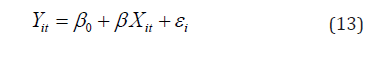

Where;

Yit= an unobservable latent variable for household poverty status (Poor =1, Otherwise = 0)

Xit = Vector of explanatory variables

X1 = Age (year)

X2= Gender (male =1, female =0)

X3= Marital status (Married = 1, otherwise =0)

X4= Education (year)

X5= Household size (number)

X6= Farming Experience (year)

X7= Operational holding (hectare)

X8= Farm acquisition status (inheritance =1, otherwise = 0)

X9= Non-farm income (yes = 1, otherwise = 0)

X10= Extension contact (yes =1, no= 0)

X11= Farm distance (kilometer)

X12= Access to credit (yes =1, no = 0)

X13= Sickness of household member (number)

X14= Security threat (yes = 1, no = 0)

β0 = Intercept

β(1-n) = Vector of parameters to be estimated

εi = Chance variable

Results and Discussion

Socio-Economic Characteristics of Cassava Farmers in the Studied Area

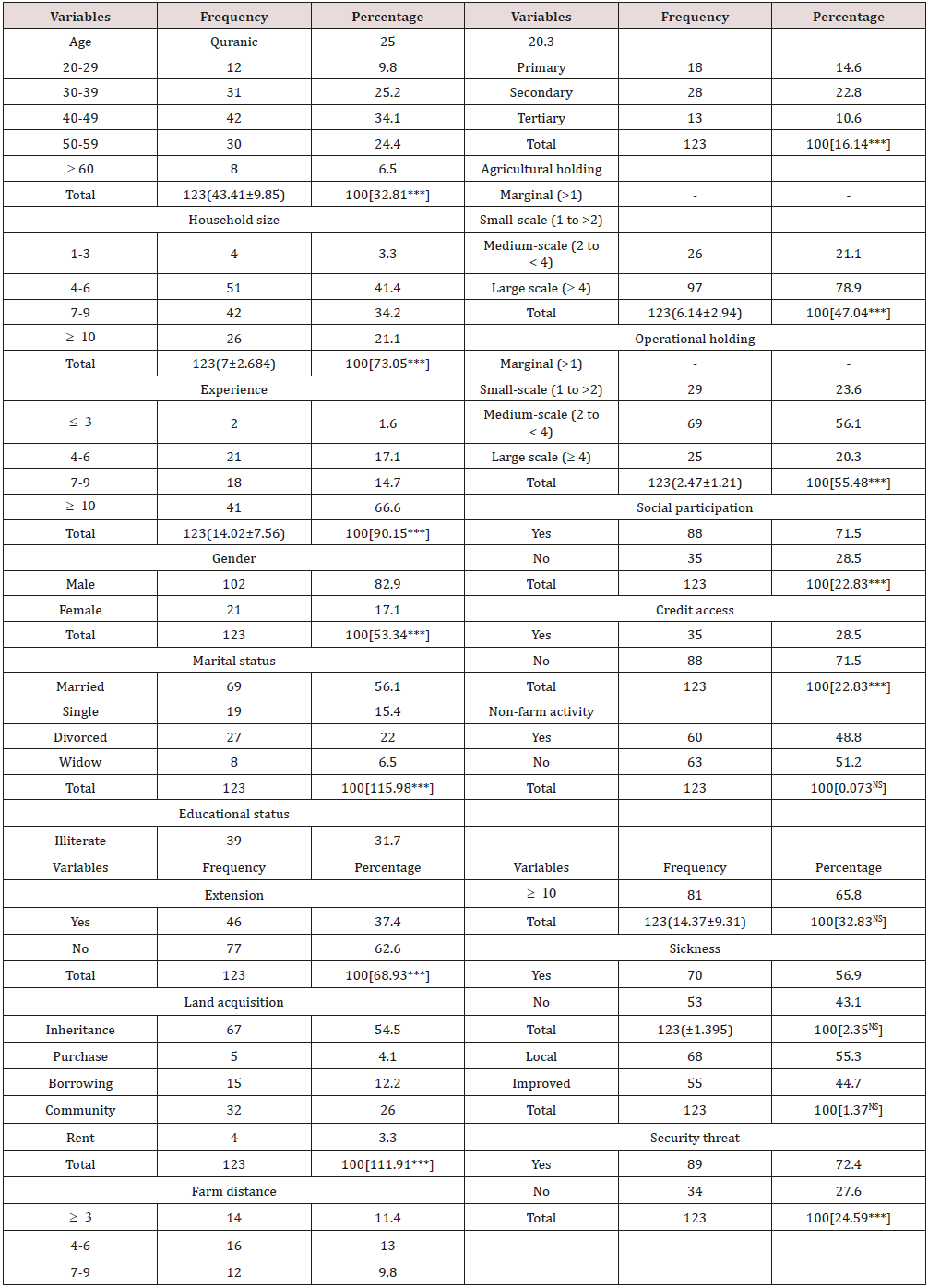

The results showed the labour force of the farming population to be active and economic viable (43.41±9.85), indicating the tendency of adoption and dissemination of cassava innovation in the studied area (Table 1). In addition, it implies that the youth are interested in cassava production. Most of the farmers had large household size (7±2.68) in order to have access to free family labour for farm operations. Most of the farmers were married (56.1%), an indication that they will pay adequate attention to cassava production in order to ensure household food security and meet up with other family expenditures. Access to productive resources and the tedious nature associated with cassava farming made the male farmers (82.9%) to have potential dominance over their female counterpart in cassava production in the studied area. The population of the farmers with literacy (68.3%) outnumbers those farmers with non-literacy, an indication that farm innovations will have wide acceptability as adoption categorization theory characterized innovators to be educated. Most of the farmers had adequate years of experience (14.02±7.56) in cassava farming which if brought to bear will make them to be rational and efficient in farm resource allocation. Most of the farmers cultivate cassava in order to augment their income and household consumption, and not purposely for commercial purpose given that the operational holding of majority (56.1%) of the farmers is medium scale.

Table 1: Socio-economic characteristics of cassava farmers in the studied area.

Source: Field survey, 2018 Note: *** NS; are 1% risk level and Non-significant; while values in ( ); [ ] are mean and standard error; and, Chi2 respectively.

However, the mean value of the agricultural holding (6.14±2.91) indicates that most of the farmers are into crop diversification in order to insulate their household food security against eventualities of risk and uncertainty. The major modes of land acquisition (inheritance and communal: 80.5%) in the studied area will not permit adoption of mechanized cassava farming as these landforms on recurrent basis are subject to fragmentation and disputes among the heir apparent and the bonafide community members. Despite that majority (55.3%) of the sampled farmers indicated that they used local cassava variety, almost half (44.7%) of the sampled farmers adopted improved cassava variety. The reason for use of local variety may be attributed to conservativeness probably because of past experience and fear of capital lost due to the failure of the improved variety. In addition, most of these farmers had no access to extension services (62.6%), thus the more reason for the adoption of local cassava variety. The labour productivity of most of the sampled farmers seems to be affected as the average kilometer of a 14.37km trek from their respective homes to farms is too far. More than half of the sampled farmers (51.2%) did not engage in non-farm activities while almost half (48.8%) of the sampled farmers partake in non-farm income perhaps in order to augment their household income base and to insure themselves against risk and uncertainty that may plaque their crop enterprise in future. Most of the farmers (71.5%) had no access to pecuniary economic advantages due to their inability to take advantage of the social capital pool in the studied area. The failure of most of the farmers to join co-operative associations might be the major reason why the majority (71.5%) had no access to credit as small to medium scale farmers in their individual capacity mostly lacks the collateral for credit advancement [13].

Moreover, lending agencies preferred to advance credit to the co-operative organization as its creditworthiness is more reliable and the cost of credit administration is relatively cheaper. Most (56.9%) of the farmers encountered ill-health challenges among their household during the last production, an indication that their stream capital base is been affected by medical expenditure towards rehabilitating the vulnerable members. In addition, an average of 1 person per household fell sick during the last production season. The quantity of family labour made available for farm operation during the last production is likely to be affected, thus making the farmers incur extra cost in hiring additional labour for farm operations. Most (72.4%) of the farmers faced security challenges especially farmers/herders’ clashes, thus indicating that the farm family food security and to a larger extent their lives were threatened during the last production period. Therefore, the study suggested the need for policymakers to engage both the herders and farmers in dialogue given that land is an indispensable resource for both agricultural activities, and the agriculture sector which is the only pivot for food security in a resource-poor economy can only thrive in a society devoid of rancor. The Chi2 values for almost all the socio-economic characteristics were significant at less than 10% probability level, an indication that the proportional distribution of each of the socio-economic variables was real and not due to chance. However, the Chi2 for socio-economic variables viz. seed variety, non-farm income and distance to the farm were non-significant, an indication that the variation in the distribution is due to chance.

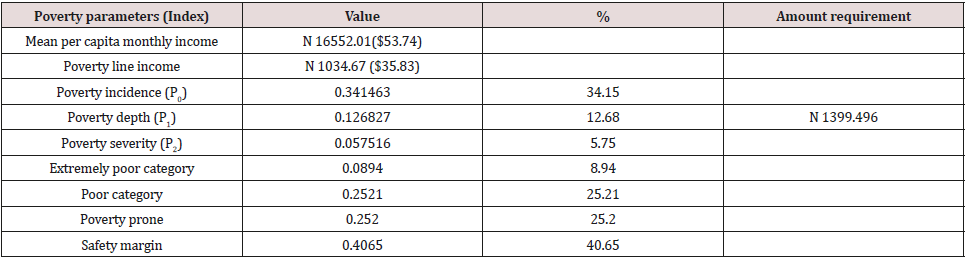

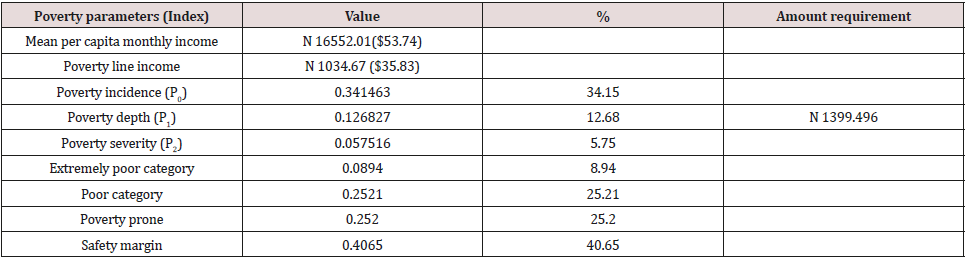

Table 2: Poverty profile of the cassava farmers.

Source: Field survey, 2018

Note: $1 is equivalent to N 308.

The results of the poverty status of the cassava farmers showed that 34.15% of the sampled cassava producers were poor i.e. were living below the poverty as their per capita monthly income is below the threshold of N11034.67 ($35.83/per capita/month) during the studied period and require approximately N1399.50 kobo ($4.54) to exit from poverty as indicated by the poverty gap index (Table 2). Furthermore, this implies that the poor cassava farmers were living on per capita income of N367.82 ($1.19) per day which is too low to make them meet up with their household daily needs. Considering the mean household size of 7 persons per household, it amounts to per capita income of N52.55 ($0.17) per family member/day which is lower than the world bank recommended international threshold of $1.90 per person/day for people living in sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, 2018). This result indicates a problem of food insecurity among the cassava farmers in the studied area as this amount will not enable them to meet-up with the recommended minimum daily calorie intake of 2250Kcal required per head per day. However, 5.75% of the sampled cassava farmers were found to be the poorest among the poor in the studied area as indicated by the poverty severity index. In addition, relying on the poverty severity index (0.0575) it can be inferred that there is no much difference in the income of the farmers who fell below the poverty line. Furthermore, the disaggregation results showed that 8.94% and 25.21% of the sampled farmers were extremely poor and poor respectively, while 25.20% of the sampled population is prone to poverty in the studied area.

Causal Factors Affecting Livelihood Status of Cassava Farming Household

Table 3: Poverty determinants of the cassava farmers.

Source: Field survey, 2018.

Note: values in ( ) are standard error; NCCP= Number of cases “correctly predicted”.

The significance of the LR Chi2 at 10% degree of freedom indicated that the logit model is the best fit for the specified equation and the parameter estimates are different from zero. In addition, the multicollinearity test result indicates absent of collinear relationship between the exogenous variables as evidenced from the variance inflation factors (VIF) which were less than 10.00 (Table 3). However, co-operative membership variable was excluded from the analysis due to high collinear relation with credit as evidenced by the Pearson correlation matrix (result not reported). The results showed the number of cases that were correctly predicted to be 97.65% of the 123 observations subjected to the analysis. It is worth to note that since the model subjected to analysis is a generalized linear model (GLM), the MacFadden R2 needs no explanation as it has little or no empirical extent as when compared to its equivalent R2 when dealing with OLS estimation. The results showed that poverty status of the cassava farmers in the studied area was influenced by almost all the predictor variables except farmers’ education, the variety of stem cuttings used, extension contact, security threat and access to credit as evidenced from the significance of the estimated coefficients at 10% degree of freedom. The positive significance of the age coefficient shows how the decline in labour efficiency as farmers advance in age will affect their income base, thus making them vulnerable to poverty. Old farmers mostly lack the strength to do the manual work that is common in local cassava production. In addition, aged farmers are more concerned about food security rather than heighten income (materialism) which in a situation of any shock in income will affect their livelihood. It should be noted that being food insecure does not necessarily implies being poor given that some people have misery attitude towards consumption. It is worth to note that consumption which is the basis for measuring food security and not poverty status is a component of income as postulated by the Keynesian theorem.

Furthermore, aged farmers are conservative and most reluctant about innovation in order not to jeopardize their farm family food security in the event of any form of risks in the future. The marginal and elasticity implications of an additional year to a farmer’s age will increase his/her vulnerability to poverty by 0.0066 and 7.589% respectively. The less family responsibility shoulder by female farmers as compared to their male counterparts with large family expenditure to carter for makes the former to be less vulnerable to poverty as indicated by the negative significance of the gender estimated coefficient. The nature of the farm family in the studied area is polygamous characterized, thus making the female parents to carter for their wards only as compared to the male parents who take the responsibility of the entire household. Even in the situation that the household head is a woman she has limited responsibility (her children) to carter for. The marginal and elasticity implications of being a female farmers/household heads will decrease vulnerable to poverty by 0.147 and 3.378% respectively. The negative significance of the marital status coefficient implies that farmers who maintained single status are less vulnerable to poverty as compared to married farmers who have many mouths to feed or expend on. The marginal and elasticity of a farmer being single will decrease his/her vulnerability to poverty by 0.199 and 3.192% respectively. The positive significance of the household coefficient means that farmers with large farm family dominated by aged, children and perhaps young ones in school, increase in the household size will not boost farmer’s income base but rather deplete his/her meager income base due to excessive expenditure on household food security and other needs required to keep the body and the soul together, thus affecting the farmers livelihood as the going concern of the business which they rely on for sustenance/ livelihood is threatened. In addition, farmers will incur extra cost in hiring extra labour required for its on-farm operation (cassava production), thus reducing his capital base thereby making them vulnerable to poverty. The marginal and elasticity implications of an additional person to a farm family household will increase the tendency of a farmer to be prone to poverty by 0.51 and 9.478% respectively.

The negative significance of the experience coefficient implies that the ability of the cassava farmers to be rational and efficient in managing their on-farm and non-farm activities will make them generate remunerative returns (high income) from farm enterprises, thus minimizing their vulnerability to poverty. The marginal and elasticity implications of an additional year of experience will reduce the tendency of cassava farmers to be prone to poverty by 0.0076 and 2.925% respectively. The negative significance of the operational holding coefficient means that farmers with large operational holdings are less likely to be poor as they are likely to have a marketable surplus to cushion any shock that will make them prone to poverty. The marginal and elasticity implications of an additional hectare to the operational holding will increase the livelihood status of the cassava farmers by 0.247 and 17.91% respectively. The negative significance of form of land acquisition coefficient indicates that cassava farmers who acquired their farms by other means other than inheritance are less likely to be poor as they have the capacity to engage in cassava commercialization which will fetch them high income as compared to those farmers who inherited their farmlands which land fragmentation and dispute over acquisition by heir apparent in the future can only permit subsistence and not commercial production of cassava, thus exposing the latter to poverty. The marginal and elasticity implications of farmers whose mode of farm acquisition is by inheritance to be prone to poverty will increase by 0.047 and 0.700% respectively. The negative significance of the non-farm income coefficient means that farmers who diversified their income sources are less likely to be poor given that they are able to insure or insulate themselves against any unforeseen eventualities (risks and uncertainty) which can threaten their continuous sustenance as against those farmers whom due to paucity of capital stick to one source of income.

Therefore, the marginal and elasticity implications of the poverty status of those farmers who earn income from non-farm activities will decrease by 0.209 and 2.908% respectively. The positive significance of the farm distance coefficient implies that farmers whose farms are far apart from their home are likely to be prone to poverty given that much of the useful time to be expended on the farm is wasted in trekking to reach the farm and also labour efficiency is affected due to fatigue, thus affecting income from cassava production due to low output productivity. In addition, some of the farmers incur costs on transportation which have implications on the meager income base. Therefore, the marginal and elasticity implications of a unit increase in the farm distance from farmer’s home will increase his/her poverty level by 0.006 and 2.298% respectively. The positive significance of the household sickness coefficient indicates that farmers facing ill-health challenges among their household members are prone to poverty given that medic’s consumption in trying to revive the sick ones is an extra cost which depletes farmers’ income base. In addition, the labour efficiency both in quantity and quality required for non-farm operation is affected as extra cost need to be incurred on hired labour to bridge the labour shortfall required for cassava production, thus affecting the income stream of the farmer. The marginal and elasticity implications of a unit increase (person) in the number of a farm family who falls sick will lead to an increase in the poverty status of the farmer by 0.034 and 1.137% respectively.

Even though that few of the idiosyncratic factors have no significant influences on poverty, their signs have little empirical extent. The positive sign of education coefficient indicates that farmers with high educational levels are likely to be prone to poverty due to their search for high paid greener pasture other than on-farm and non-farm activities which are presumed to be dirty jobs meant for jobless people in the rural areas. The negative sign of extension contact coefficient means extension agents deviate from their mandate as they discuss political matters with farmers other than farm innovation, thus making farmers with access to extension contact vulnerable to poverty as valuable time supposed to be spent on farm operations is wasted. The positive significance of the stem cuttings variety though non-significant implies that those farmers who cultivated local variety of cassava will harvest low yield of cassava output which in turn will translate into low income which can hardly liquidate the cost of cultivation more less the household expenditure, thus making them susceptible to poverty. Therefore, if the going concern of the on-farm business is affected, then the livelihood of the farm family who depends on farm income as a source of livelihood sustenance will be in jeopardy. The inverse relationship of access to credit means that farmers who had access to credit were prone to poverty given that the credit advanced was not productive as it was used for a purpose other than investment i.e. capital consumption and not capital investment, thus affecting their income base due to retirement when the credit matures. The positive sign of security threat challenges implies that those farmers who faced security challenges viz. farmers/herders’ clashes and communal conflicts have their income base affected due to low return as a result of low cassava output, thus making them prone to poverty.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Based on the results it can be concluded that the majority of the sampled farming population is dominated by economically viable able-bodied young farmers who had interest in cassava production. However, more than one-quarter of them were found to be too poor to meet up with their household needs which owe to age, large household composed of weak people, long distance to the farm and sickness related matters affecting the farm family. Therefore, the study recommends the provision of social intervention to improve the livelihood status of aged farmers, advice farmers on the imperativeness of sustainable livelihood, provision of social amenities to improve the livelihood of cassava farmers in the studied area, thereby enhancing the value chain of cassava production in the studied area. Provision of social protection in the studied area will encourage poor households to invest in riskier but more remunerative livelihood activities, thereby reducing liquidity constraints and supporting labour mobility. The social protection programmes should be designed in such a way that it should link the social benefits to direct promotion of rural employment and agricultural production i.e. linking public export schemes, food purchase schemes and school feeding programmes to smallholder cassava farmers as suppliers. Social protection can also help to contain income inequality and promote a more equitable and sustainable pathway of structural transformation and growth. The provision of social protection programmes will go a long way in fostering a healthier, better-educated population and a more skilled workforce capable of responding to changing demand and joining the transition to higher levels of cassava productivity in the studied area and the country in general.

References

- Sengul S, Tuncer I (2005) poverty levels and food demand of the poor in Turkey. Agribusiness 21(3): 289-311.

- Olubanjo OO, Akinleye SO and Soremekun WA (2007) Poverty determinants among farmers in Ogun State, Nigeria. Medwell Agricultural Journal 2(2): 275-280.

- Swastika DKS, Hardono SG, Supriyatna Y, Purwantini TB (2007) The characteristics of poverty and its alleviation programmes in Indonesia. Palawija Newsletter 24(3): 5-8.

- FAO (2017) The state of food and agriculture 2017-leveraging food systems for inclusive rural transformation.

- Atemnkeng JT (2015) The nexus of economic growth, inequality and poverty reduction: The role of the Cameroon labour market. In: Addressing poverty and inequality in the post 2015 development agenda. Proceedings of the African Economic Conference 2015 held in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, p. 6-35.

- Sabir HM, Hussain Z and Saboor A (2006) Determinants of small farmers poverty in the Central Punjab (Pakistan). Journal of Agriculture and Social Sciences 2(1).

- Owuor G, Ngigi M, Oumaand S and Birach EA (2007) Determinants of rural poverty in Africa: The case of small holder farmers in Kenya. Journal of Applied Sciences 7(17): 2539-2543.

- Ogbonna MC, Onyenweaku CE and Nwaru JC (2012) Determinants of rural poverty in Africa: the case of yam farm households in Southeastern Nigeria. International Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development 15(2): 1129-1137.

- Anonymous (2007) Part 2: Adjusting for differences across individuals. Constructing the welfare aggregate. Bosnia and Herzegovina Poverty Analysis Workshop.

- Sadiq MS, Kolo MD (2015) Poverty profile of rural farming household in Niger State and its implication on Food security in Nigeria. International Journal of Agricultural Research and Review 3(2): 161-171.

- World Bank (2013) World Development Report (WDR). Oxford University Press, UK.

- Foster JE, Greer J, Thorbecke E (1984) A class of decomposable poverty measures. Econometrica 52(1): 761-766.

- World Bank (2018) 2018 World Hunger and Poverty Facts and Statistics.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...