Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4676

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4676)

Can Socio-Economic Incentives Improve the Livelihoods of Communities Surrounding Rehabilitated ecosystems? An empirical evidence of Kondoa Rehabilitated Rural Areas, Dodoma, Tanzania Volume 1 - Issue 3

Chami Avit A*

- Department of economic studies, The Mwalimu nyerere memorial academy, Tanzania

Received: March 01,2018; Published: March 13,2018

Corresponding author: Chami Avit A, Department of economic studies, The Mwalimu Nyerere Memorial Academy-Zanzibar Campus, The Mwalimu Nyerere Memorial Academy, Tanzania

DOI: 10.32474/CIACR.2018.01.000115

Abstract

Communities need motivation in order to effectively and sustainably participate in conserving the surrounding environmental resources. However the contribution of socio-economic incentives towards improving the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems remains scantly known. This study was an attempt to reveal the less known contribution of socioeconomic incentives towards improving the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems drawing empirical evidences from Kondoa Rehabilitated Rural Areas (KRA), Dodoma, Tanzania. The cross-sectional research design was employed. Simple random sampling technique was used to select 30 respondents from each of the four study villages and make a total of 120 respondent households.

The study was conducted in Mafai, Ntomoko, Kalamba-Juu and Kalamba-Chini villages. Data were collected using pre-tested and pilot-tested questionnaires, focus group discussions and interviews. Ms-Excel and SPSS 20.0 computer software were used to analyze data. Descriptive statistics were employed to reveal various parameters in the study. Chi-square test was further employed to reveal the contribution of economic incentives on the total household income. The study findings revealed five socio-economic incentives which are widely adopted in the KRA namely tree seedlings, fertilizer, improved seeds, beekeeping inputs and education programs. It was further reported from the study findings that the income earned from practicing activities related to socio-economic incentives to be high as it accrues 61% of the total household income.

The Chi-square test further revealed that contribution of socio-economic incentive to total household income is statistically significant at p<0.05. It was concluded from the study findings that socio-economic incentives were highly useful towards enhancing household income and consequently resulting to positive outcomes to the livelihood activities prevailing in the area. The adoption of socio-economic incentives was found quite useful in the course of improving the livelihoods of the households in KRA hence leading to sustainable conservation of the biodiversity resources in KRA. Based on the study findings, the conservationists, environmentalists and policy makers are hereby urged to effectively capacitate the communities surrounding the rehabilitated rural areas with an indepth understanding of how to utilize and commercialize the applied socio-economic incentives so as to effectively conserve the surrounding biodiversity resources while earning substantial income in return.

Keywords: Socio-economic incentives; Livelihoods; Rehabilitated rural areas

Abbrevations: KRA: Kondoa Rehabilitated Rural Areas; NEMC: National Environmental Management Council; LAMP: Land Management Program; HADO: Hifadhi Ardhi Dodoma; HASHI: Hifadhi Ardhi Shinyanga; HIMA: Hifadhi Mazingira Project; SCAPA: Soil Conservation and Agro-forestry Program; KEA: Kondoa Eroded Area; UMBCP: Uluguru Mountain Biodiversity Conservation Project; WCST: Wildlife Conservation Society of Tanzania; UMADEP: Uluguru Mountain Agriculture Development Project

Introduction

Background information

According to IUCN [1] many of the most biodiversity rich ecosystems and species in Eastern Africa lie in remote rural areas that are physically or financially beyond the reach of government environmental and protected areas agencies. Their conservation depends primarily on the actions of the surrounding local communities which are mainly characterised by poor, limited and insecure livelihood base. A substantial body of literature posits that the majority of communities surrounding potential ecosystems and species depend on resources from the surrounding biodiversity for their day-to-day subsistence and income as they often have few alternatives for securing their livelihoods. The provision of socioeconomic incentives for these community members to conserve biodiversity is of paramount importance since community economic incentives are based on allowing local communities opportunity to benefit from conservation [2,3]. There have been wide applications of numerous environmental conservation strategies in the course of arresting the prevailing degradations and fragmentations of ecosystems in many areas in the world. The existing strategies have been dominated by two approaches namely protectionist approach and economic incentive provision approach. Protectionist approach attempts to fence off or reserve areas for nature and exclude people from the reserved areas [4].

According to Guthiga [5] this protectionist approach has been labelled as the 'fortress conservation', 'coercive conservation' or 'fence-fine' and it has dominated mainstream thinking in conservation for a long time. On the other hand economic incentives approach refer to specific inducements designed and implemented to influence government bodies, business, non-governmental organisations, or local people to sustainably and responsibly conserve, utilize and manage environmental resources whereas socio-economic incentives mostly reflect livelihood measures that strengthen and diversify the livelihoods of biodiversity users or residents of biodiversity areas [6]. The economic incentives approach aim at influencing people's behaviour by making it more desirable for them to conserve, rather than degrading or depleting environmental quality through communities’ course of their livelihoods' activities [1-3,7]. Tanzania has been widely acknowledged as one of the most important nations in Africa for biodiversity conservation with more than 25% of the Tanzania mainland total area been set-aside as a protected area [8]. The initiatives of allocating protected areas in the country go in line with rehabilitation initiatives which partly enhance the existing biodiversity conservation including Eastern Arc Mountains, Wetlands, Marine and Fresh Water Areas, forest reserves and partly enclose, improve and establish new biodiversity conservation areas including eroded and infertile areas. There have been deliberate initiatives by the government and donors to rehabilitate, restore and promote the recovery of the degraded ecosystems in Tanzania [9].

Towards arresting environmental degradation, a number of national, regional and district level programs were established including the formulation of the Division of Environment in the Vice President’s Office, the National Environmental Management Council (NEMC), and the Land Management Program for Environment Conservation (LAMP) in Babati District. Other programs are the Hifadhi Ardhi Shinyanga (HASHI) project, the Hifadhi Ardhi Dodoma (HADO) project, the Hifadhi Mazingira project (HIMA) of Iringa, the Soil Erosion Control and Agro-forestry Program (SECAP) in Lushoto District, and the Soil Conservation and Agro-forestry Program (SCAPA) in Arumeru District [10]. Hifadhi Ardhi Dodoma (HADO) is a soil conservation project which started in 1973 in several areas of Dodoma Region, aiming at reducing land degradation in rapidly deteriorating areas through physical soil conservation measures such as afforestation, appropriate cultivation methods, control of run-off by contour band construction and planting vegetation in the river beds [11-14]. Among other drastic measures, HADO project evicted all forms of human activities and all livestock from the 1256 km2 of Kondoa Eroded Areas in 1979 [15,16].

These led to the quick land rehabilitation entailing high restoration of soil fertility and vegetation in the worst affected areas which later became known as Kondoa Rehabilitated Areas [14,17]. Kondoa Rehabilitated Areas (KRA) are among rehabilitated protected rural areas found in the central of Tanzania. The present situation in KRA indicate that they face enforcement and administration inefficiency towards handling exploitation pressures from local communities surrounding the rehabilitated protected areas [14,18]. This is due to the fact that KRA hold the entire source of livelihoods for the surrounding rural communities hence subjects the rehabilitated protected areas to an intensive reliance and dependence on the resources for sustaining their livelihoods [18,19]. In line with weaknesses and deficiencies of the existing command and control measures in place, there has been an experienced rampant increase of unsustainable land-uses and other human activities in the areas [14,18,20]. Moreover, the successful rehabilitation of Kondoa areas attracted many human activities including farming, house building (brick making and burning, building poles, thatch grass, ropes etc.), tree felling for fuel wood and farm expansion, and sporadic grazing of livestock [18,21].

Literatures suggest successful rehabilitation constrains such as over extraction of the available resources, unsustainable land uses and poor institutional framework which exist along the resettlement process have made the resettlement process unsustainable [22,23]. The existing situation in the areas also demonstrates that farmers and livestock keepers grasp quickly whatever chances happen to make use of new land-use opportunities, unlike early 1970s when intensive conservation efforts existed in the areas [18,20]. In contrast to the prevailing situation in Kondoa Rehabilitated Areas, various approaches of environmental management measures have been employed to protect the natural resources and ensure sustainable livelihoods in the area. Traditional environmental management approach namely command and control measures has been practiced unsuccessfully, whereby enacted legislations, policies and regulations in place provided little control on existing rapid human activities and unsustainable land uses [14,17].

Equally, the measures implicate minimum legal measures against the offenders on various issues mentioned in the district environmental protection by-laws due to poor and weak institutional framework [24]. Meanwhile, application of socioeconomic incentives approach of environmental management has been widely used in the area with little knowledge and information on the contribution of socio-economic incentives towards improving the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems hence the rationale of undertaking this study. This study was an attempt to reveal the less known contribution of socio-economic incentives towards improving the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems drawing empirical evidences from Kondoa Rehabilitated Rural Areas, Dodoma, Tanzania.

Problem statement and study objectives

The substantial body of literature corroborates the existing wide understanding of the significant merits of socio-economic incentives measures over command and control measures of environmental management measures [2,3,6,7]. The widely posited socio-economic incentives’ significances including their least-cost efficient means of sustainably conserving environmental ecosystems as they drive up the cost of environmentally harmful social, economic and livelihoods activities and increase the returns from conservation activities [1,3,25,26]. Despite the existing wide understanding on the merits, significances and challenges of socio-economic incentives in the course of enhancing biodiversity conservation initiatives [2,3,6,7] still the contribution of socio-economic incentives towards improving the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems remains skimpy known.

This study was an attempt to reveal the less known contribution of socio-economic incentives towards improving the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems drawing empirical evidences from Kondoa Rehabilitated Rural Areas, Dodoma, Tanzania. The study findings provide useful inputs for conservationists, environmentalists and policy makers. The underscored contribution of socio-economic incentives towards improving the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems is useful in the course of making use of designing effective environmental conservation measures which integrates community livelihoods at large. The fact that REDD+ programs have been widely accounted to result into positive and significant impacts on communities livelihoods at the household level Bond 2009, the revealed contribution of socio-economic incentives towards improving the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems stands as useful inputs for helping in intensifying impacts of REDD+ projects, hence scaling-up the available livelihoods options to communities and households surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems.

Therefore, the overarching objective of this study was to assess the contribution of socio-economic incentives the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems by drawing empirical evidences from Kondoa Rehabilitated Rural Areas (KRA), Dodoma, Tanzania. Specifically, this study sought to:

a) Assess the adopted socio-economic incentives in KRA.

b) Determine the income accrued by KRA surrounding

communities from practicing socio-economic incentives.

c) Assess the contribution of economic incentives to the livelihoods of KRA surrounding communities.

Research Methodology

Description of the study area

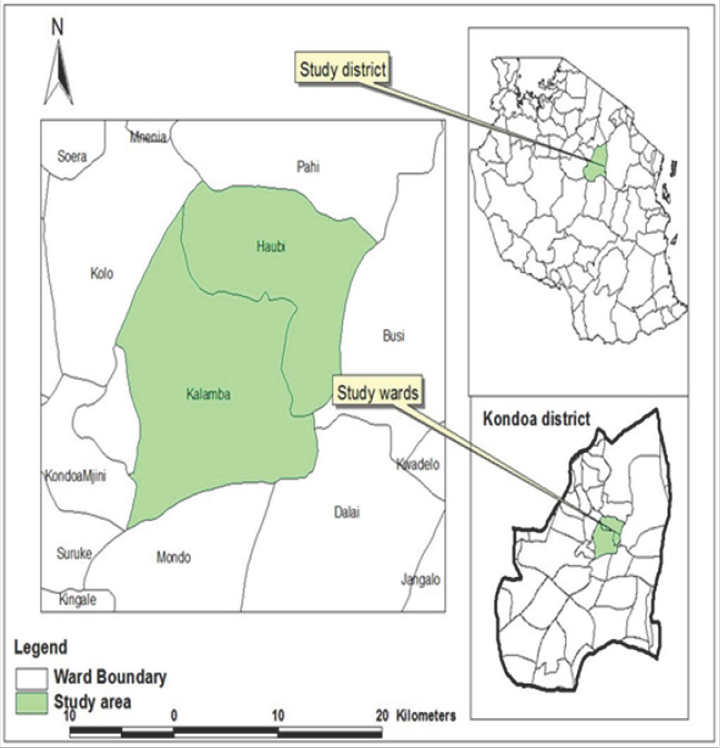

Location: The study was conducted at Mafai, Ntomoko, Kalamba juu and Kalamba chini villages in Haubi and Kalamba wards respectively. The study villages and its human settlements are bordering Kondoa Rehabilitated Areas. The study area is found in Kondoa District, Dodoma Region in central Tanzania and it is located at S40 43" 28' E350 50" 2’. According to Mbegu 22, the study area has semi-arid climatic conditions and nearly ten percent of Kondoa District area with about 1256sq.km. The study area was categorised as being severely degraded, and hence was referred to as the Kondoa Eroded Area (KEA). This calls sound rehabilitation measures which turned KEA into Kondoa Rehabilitated Area (KRA) [15]. Currently, human activities have been reintroduced in study area with high prevalence of livelihoods activities on the resources from the rehabilitated closed area [22]. The fact that the selected study villages border some of the forest reserves found in Kondoa Rehabilitated Areas was the criteria for the selection of the study villages.

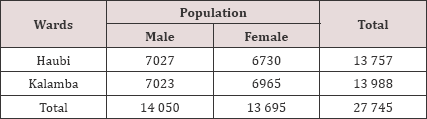

Population: The population found in the villages surrounding Kondoa Rehabilitated Areas is mainly composed of Rangi tribe. Current the study area population is mainly dominated by male who account for 51 of the total population in the area as shown in (Table 1).

Table 1: Population profile of the Haubi and Kalamba wards in KRA.

Economic activities: The successful rehabilitation of the eroded areas which took place in 1970s attracted many human activities including farming, house building (brick making and burning, building poles, thatch grass, ropes etc.), fuel wood and fertile land for farm expansion and sporadic grazing of livestock hence high population and settlement increase [18,21]. Subsistence farming is dominant in Haubi and Kalamba wards and it stands as the main economic activity and source of livelihoods for many households in the area.

Food crops are maize, sorghum, pearl millet and sweet potatoes while cash crops include sunflower, groundnuts, simsim, finger millet and peas [27]. Livestock keeping occupies the second important position to farming whereas cattle, goats, sheeps, donkeys and chicken are kept by the majority of the households in the area [27]. Of recent, changes of climatic conditions and loss of soil fertility have led to low productivity hence exacerbating poverty among the majority of the households in the area (Ndanga, 2012).

Research design: This study employed a cross-sectional research design. Under this design, data on the variables of interest were collected more or less simultaneously, examined once, and the relationship between variables determined [28]. The employed study design was advantageous as it was compatible to the available time and resources.

Sampling procedures

Two wards namely Haubi and Kalamba were purposively selected for this study. The study wards which were of two categories; Haubi was in the category of the ward bordering the protected Ikome forest reserves and sometimes referred to be inside KRA and the Kalamba ward was in the category of ward found outside KRA. In considering the time available for conducting the study as well as financial resources available, two villages were randomly selected from each of the study wards to constitute the sampling frame for the study. Using simple random sampling technique of drawing playing cards, four villages were selected from the study wards namely Mafai, Ntomoko, Kalamba-Juu and Kalamba-Chini. The study population was formed of the total number of households from the four randomly sampled villages.

The households were randomly picked from the village register books in which all households' heads were listed. In villages where register books were absent, the names of people residing in the particular village were recorded with the assistance of village leaders from each hamlet and simple random sampling was used through random generated numbers technique so as to avoid bias. Key informants were purposively selected based on the positions they hold in relation to conservation and rehabilitation of KRA. These included HADO staff in KRA, village government chairpersons and executive officers, institutions representatives and village elders from the selected four villages in the study area.

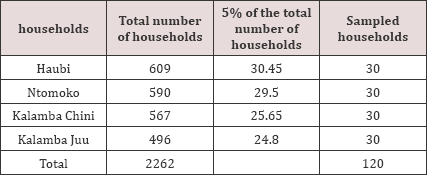

Sample size determination

The households residing in each village were randomly drawn from the compiled list of village registers which was used as a sampling frame for the study. The study went across the sampling frame of the total number of the households available in the study area as proposed by the study such that the provided sampling technique gives a standard sample size which could reasonably represent the population in the question Kothari, 2004, Babbie, 2007. Boyd 1981, cited by Njana [29] recommended a sampling intensity of 5% of total number of households in a study site. Boyd 1981 further posits that the study sample size is considered adequate and able to fit statistical analyses if and only if it entails the reasonable proportion of the units from the sampling frame but being not less than 30 units. For the purpose of this study a sampling intensity of 5% was adopted. This was equivalent to 120 households meaning that 30 households were randomly sampled from each of the four villages as presented in the (Table 2).

Table 2: Distribution of respondents in the surveyed villages.

Data collection

Towards addressing the study specific objectives, both primary and secondary data were collected. A combination of both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods were used to achieve triangulation and complementary. The combination also increased the validity of results [28]. Before actual data collection, research instruments were calibrated by pre-testing and pilot testing of the study data collection tools in the10 households; five households from each ward where actual data collection was to be done. The analysis of the tested instruments was done to improve the instruments' consistency, validity and reliability. In the course of collecting data various data collection methods were involved including Household questionnaire survey, Key informants interviews, Focus group discussions and Literature Review were employed to yield both primary and secondary

Data processing and analysis

After data collection exercise, primary data were checked for completeness before coding, entering and verification for analysis. The filled questionnaires were cleaned to remove all unintended information and were made ready for coding. The coding process resulted to the data entry exercise. The entered data were cleaned to resemble the collected information. Microsoft Excel and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 20.0) computer programs were employed for proper housekeeping, arrangement, management and analysis of the collected data. Data analysis for each objective was rigorously performed, presented and discussed. Chi-square test was used analyse the contribution of economic incentives to total household income in the study area.

Results and Discussions

Socio-economic characteristics of respondents

This study shed light on the relevant social-economic characteristics of the 120 respondents who were involved in this study. The characteristics include age, sex, education, marital status and occupation as they are summarized and presented in (Table 3). Respondents' characteristics were important in order to provide a snapshot on the background of the respondents and their suitability for this inquiry.

Table 3: Socio-economic characteristics of respondents (n=120).

Age of respondents: The fact that most (60.8 %) of the heads of respondents were aged between 41 and 60 years and 37.5% of the heads of household in study villages were aged between 20 and 41 years which is considered as the productive or working age, it implies availability of the workforce in various economic and conservation activities. Since the study found that many heads of household in the study villages were aged within the productive age, the study finding is in line with Giliba [30] assertion that most of people found in the study villages can effectively participate in environmental conservation activities, adopt and utilize the economic incentives available in the study area. This suggests that age is useful socio-economic characteristic in influencing sustainable management of biodiversity conservation initiatives. This finding supports Njana’s [29] assertion, that the respondents aged between 20 and 60 years provide a workforce in various economic and conservation activities.

Sex of respondents: The study findings presented in the (Table 3) shows that 60% and 40% of the total households are the male and female headed households respectively suggests the presence of encouraging level of participation in various household responsibilities. The study findings which shows 60% and 40% of total male and female respectively in the study area is widely supported by Stiglitz [31,32] and Njana [29] as they are quite revealing and depicting the usefulness of sex of household heads towards adaptation of sustainable environmental conservation initiatives including the adoption of socio-economic incentives in the study area. Stiglitz [31] considered high level of women participation useful towards achieving sustainable development and poverty alleviation through high level of community participation. Also the finding is in line with Ockiya [33] and Adhikari [34], who found that the presence of majority of both sex i.e. 60% and 40% male and female headed households in the study area respectively suggests high level of community participation in the study area. This among other things suggests a supportive condition for sustainable adaptation of sustainable environmental conservation initiatives including the adoption of socio-economic incentives in the study area.

Respondent's education levels: Education level of individuals within a particular community is an indicator of the level of community's human capital. Study findings in (Table 3) showed that the education levels of household heads who took part in this study were 30.8% with no formal schooling, 41.7% had acquired primary school education, 26.7% had acquired secondary school education while few (0.8%) of the household heads had acquired tertiary education. The revealed high number of people who had no formal schooling (30.8%) was due to the fact that the number included people with adult education in the study area which entails members of population who had indigenous knowledge which equips them with basic life skills including environmental conservation and seasonal farming. The revealed study findings concurs with what was reported by Kessy [35] and Njana [29] that higher level of education puts households in better understanding of existing livelihood challenges, better decision making ability to choose better alternative solutions to existing problems and undertake household livelihood strategies which are environmentally friendly.

On the other hand Maro [36] and Kamwenda [37] argued in line with the study findings that the level of education is considered as an important factor at household level, because, the higher the literacy rate of the household head, the higher the probability the household head is able to make sensible decisions regarding household livelihoods in relation to the sustainable utilization of the available natural resources. The high literacy level of the household heads of more than 69.2% revealed from the study area (Table 3) was a sufficient precursor of high level of awareness in many aspects hence becoming an influential socio-economic character which can highly influence the community to sustainably adopt effective and sustainable environmental conservation initiatives including socioeconomic incentives in the study area. The revealed respondents' education level was envisaged to be a useful determinant of the level of understanding of the merits and demerits of adopting and utilizing economic incentives.

Marital status of the respondents: The study findings revealed 7.5% of the heads of the households in the study area were single, 87.5% were married, 3.3% were divorced and 1.7% was widowed as presented in the (Table 3). The fact that the majority of respondents from the study area were married, the results support the African traditional setting that for the household to exist there should be a couple of married individuals. This implies the presence of families with a good number of children and siblings in a particular community hence an indicator of the level of family workforce to support several economic activities in the study area.

Economic activities: The findings reveal that the household heads participated in answering survey questionnaires are mainly engaged in three economic activities namely crop farming, livestock keeping and formal employment. This implies that the livelihoods of the majority of household involved in this study depend on available natural resources. Following the results presented in the (Table 3), the following subsections are discussions of the presented results.

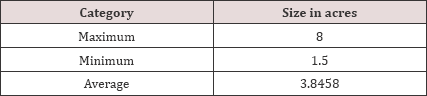

Crop farming: The study revealed that 35% of the household heads participated in the study were crop farmers as presented in the (Table 3). The average size of the farms owned by the respondents was found to be 3.8458 acres with minimum 1.50 acres and maximum of 8.00 acres respectively as presented in (Table 4). The majority of the households in the study villages were involved in farming maize, beans, sunflower, groundnuts and vegetables. The farming activity in the study area was found to be very subsistent since almost all famers in the study area were found using hand hoes in their farming. This finding is in line with Kessy [35], Njana [29] and Giliba [30], who found that the majority of farming activities in rural areas is subsistent. This implies high reliance and dependence to other economic activities to support their livelihoods.

Table 4: Farm sizes of the respondents.

Crop farming and livestock keeping

The study revealed majority of the households in the study area (64.2%) were involved in both crop farming and livestock keeping as presented in (Table 3). These activities engage many people in the study area as they also apply in-house livestock feeding system. In-house livestock feeding system was reported to be practiced by using the residuals from the harvested crops from the owned farms to feed livestock. The in-house livestock feeding system reduces the encroachments to the forest reserves in the study area. The study found that the number of livestock allowed to be kept in the particular households was 4 cows and 6 goats, the tendency which was instituted in the study area since the existence of HADO project in 1973. The revealed findings from the study area are in line with Ogle [38] and Kangalawe [16] who reported that the controlled forms of human activities in the then Kondoa Eroded Areas in 1979 had made significant contribution to the conservation initiatives. The prevailing controlled environment for all forms of human activities which has been laid by the HADO project provides sustainable conditions for sustainable environment conservation in the study area [30].

Formal employment

The study found 0.8% of the total number of households in the study was engaged in the formal employment as presented in (Table 3). The formal employed respondents were teachers and executive officers at wards and village levels. Despite of being formally employed the respondents were engaged in the subsistent farming and rearing of livestock for supporting their livelihood needs since they were done in the households premises. The study findings on the prevailing main activities in the study area concurs with what was reported by Abdallah and Sauer [39] that, farming employs over 80% of the rural households. The reported 0.8% of the households' heads who are engaged in the formal employment implies that farming is the dominant livelihoods activities for the majority of the community members in the study villages.

Adopted socio-economic incentives in kondoa rehabilitated areas

The findings emanating from this study revealed various socioeconomic incentives which have been adopted by the community. The fact that the socio-economic incentives under study are meant as specific inducement designed to influence local people to conserve the surrounding biological diversity resources or rather to use its components sustainably. The study has shed light on the mainly adopted socio-economic incentives in the study area, so as to be able to underscore their significances in improving livelihoods of the communities in the study area.

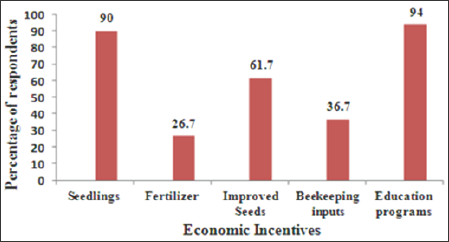

Socio-economic incentives practices have taken place in the area in form of creation and adoption of new tech-nologies which were needed to systemically change consumption and production patterns, and might entail significant price corrections; encourage the preservation of natu-ral endowments; reduce inequality; and strengthen economic governance of the communities in the area hence sustainable conservation. The study revealed five main socio-economic incentives which are adopted in all of the four study villages in Kondoa Rehabilitated Areas. The reported prevailing socio-economic incentives are provision of tree seedlings, fertilizer, improved seeds, beekeeping inputs and education programs. The number of respondents who were aware on the given socioeconomic incentives is presented in the (Figure 1). The existence of the HADO project in the study area since 1973 has provided a base for the existence of environment conservation initiatives including socio-economic incentives in the area. This has helped in reducing the rate of encroachment in forest reserves and other protected areas hence attaining sustainable environment conservation in the study area while improving their livelihoods.

Tree seedlings: Tree seedlings serve as an important component in tree planting. The study found the supply of tree seedling to the communities as the main incentive towards encouraging them to participate in tree planting and hence biodiversity conservation in the study area. The fact that tree planting serves a number of ecological and service functions in the ecosystem, it has been reported by 90% of the respondents in the study area as presented in (Figure 1). The supply of free tree seedlings influence respondents to plant or retain trees since rural communities have little financial and material resources for preparing their own tree nurseries.

Figure 1: Map showing location of the Study Area.

The findings are similar to the findings reported by Kiwale [40] and Butuyuyu [41] who found that tangible incentives in form of free tree seedlings significantly influenced the number of planted trees in Magu and Same districts respectively. The respondents in the study area reported that tree seedlings has increased the willingness of people to plant more trees if they are supplied free of charge. The supplies of free tree seedlings in the study area was found to influence many farmers and other community members to plant trees in their farms and reduce reliance on natural forest products. It was also found to earn income from selling the tree seedlings for the few individuals who had private tree nurseries as one seedling was worth up to 1000 TAS depending on the age, size and height.

Fertilizer: The study found that the supply of fertilizer to the communities in the study area could serve as an incentive since the community is composed of more than 99% people who are engaged in farming related economic activities as presented in (Table 3). It was found that 26.7% of the respondent from all of the study villages prefer fertilizer as it is useful in improving their crop yield and hence income. This study finding is concurring to Giliba [30] that the inadequate land for producing sufficient food to feed a mean household size of 6 individuals requires technology for improving the land productivity. Besides, it was observed that the use of fertilizer results to good harvests and hence being one of the plausible reasons for encouraging the small sizes of cultivated land and meeting the rapidly growing population needs in the study area.

Improved seeds: Improved seeds were found as a useful socioeconomic incentive by 61.7% of the respondents in the study area. The fact that 99% of all people are engaged in farming related economic activities, improved seeds could be useful in improving farming yield and hence raising productivity and income. The study finding are similar to that by Lalika [42] and Giliba [30] who reported that that improving farming technologies for farmers essentially makes them not relying too much to the expanding farming lands to the forest reserve. The study finding suggests that supplying improved seeds to the communities can serve as an incentive. Since the improved seeds increase yields from the same farm sizes, the communities continue cultivating the existing land sizes without expanding them to the forest reserves. The adoption of the improved seeds can work as one of technological interventions towards improved farming productivity in the study area hence resulting to the improved livelihoods and environmental conservation initiatives.

Beekeeping inputs: The study findings revealed beekeeping inputs as a useful socio-economic incentive as 36.7% of the respondents involved in the household questionnaire survey mentioned it to be useful in their areas. Honey collection was one of the economic activities undertaken in some of the areas in the study villages. Beekeeping and honey hunting were practiced in most of Mafai and Ntomoko areas as they have a long history of traditional beekeeping and honey hunting practice. Beekeeping and honey hunting was found useful in both conservation and improving livelihoods in the study area as they were done in the general land forests, protected areas, farmlands and woodlands.

The study finding concur Kowero and Okting'ati 1990 and Fischer [43] findings that beekeeping and honey collection activities in the forest reserve are friendly activities which encourage regeneration of plant species as they also protect forest from degradation in the same time. However, honey collection was not an important income generating activity in the study area, as local people are not mainly practicing beekeeping but if well promoted and modernized beekeeping inputs could work positively towards improving conservation practices and income generation for the livelihoods for the communities surrounding the forest reserve.

Education and training programs

Education and training programs were found to be useful socioeconomic incentive towards making people engage in environmental conservation practices. The study findings revealed 94% of respondents mentioning it as useful socio-economic incentive as presented in (Figure 2). According to Benabou [44], education and training programs are non-monetary incentives that may include study tours and short courses. Like monetary incentives, the purpose of non-monetary incentives is to encourage individuals, communities or organizations to carry out conservation activities sustainably. Sometimes non-monetary incentives are given as reward to individuals, communities and organizations for excellent job performance. Education and training programs were provided to raise level of awareness and sustainably build up their capacity to be able to link conservation practices and their livelihoods. These findings agree with observation by Bakengesa 2001 and Ndomba [45] studies which indicated the need of education and training programs in influencing communities to adopt newly introduced interventions. Furthermore, Giliba [30] findings were similar to the study findings, that regular education and training programs enhances the ability of the community to manage their surrounding biodiversity resources and to sustainably accrue livelihoods from the resources.

Figure 2: Adopted economic incentives in the study area.

Level of income accrued from practicing socio-economic incentives in KRA.

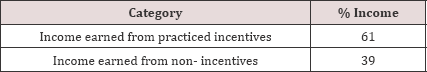

The study findings further revealed the level of income accrued by KRA surrounding communities from practicing socio-economic incentives. The fact that income was one of the important livelihood aspects which touches almost every household in the area, it tells also the level of the revealed variations in wellbeing and access at an individual or intra-household level among the communities which highly depend on the practicing socio-economic incentives in the rehabilitated areas. The revealed contribution of socio-economic incentives to the total household income is presented in the (Table 5) herein.

Table 5: Contribution of socio-economic incentives to the household income (n=120).

The revealed socio-economic incentives in the study area were directly related to various components of the livelihoods of the surrounding communities. Since the most complex the portfolio of income and assets out of which people construct their living including annual income the households head earns, tangible assets such as stores, resources as well as intangible assets such as claims. The study revealed 61% of the total annual income of the heads of households in KRA being accrued from practicing the widely adopted economic incentives. This implies by practicing socioeconomic incentives in the particular household, 61% of the total annual income will be earned hence being a very useful intervention improving household livelihoods while encouraging communities to sustainably conserve their surrounding biodiversity.

From the results presented in (Table 5), it is reasonable to argue that income accrued from practicing activities related to economic incentives have sizeable contribution to total household income. Using income as a proxy of livelihoods it is arguable that the adoption of economic incentives is useful towards improving household livelihoods. The fact that income earned from practicing activities related to socio-economic incentives was reported to be high (61%) implies that the adoption of socio-economic incentives is quite useful towards improving the livelihoods of the households in KRA. This study finding implies high usefulness of socio-economic incentives towards enhancing household income and consequently resulting to positive outcomes to the livelihood activities prevailing in the area. High prevalence of economic incentives practiced in the area provides opportunity in practice to restore general forest and the entire biodiversity resources in the rehabilitated areas.

Contribution of economic incentives to the livelihoods of KRA surrounding communities

The fact that the revealed adopted socio-economic incentives serve dual roles including enhanced and sustainable conservation initiatives including restoration of biodiversity loss and fragmentation, they also improve the livelihoods of the communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems. In the course of examining the contribution of economic incentives on the livelihoods of the KRA surrounding communities, income was used as a proxy of community livelihoods. It was therefore sought reasonable to use Chi-square test to further analyse the contribution of economic incentives to total household income.

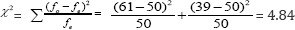

Chi-square test: Chi-square test was used to further analyse the contribution of economic incentives to total household income. Prior to analysis, the quantified contributions (Table 5) were re-organised into Chi-squared frequency Table namely: (a) contribution of economic incentive to total household income— with expected frequency, fe, of 50% and observed frequency, fo , of 61%, (b) contribution of non- economic incentive to total household income —with expected frequency, f, of 50% and observed frequency, fo , of 39%. Then, the chi-squared (x2) was computed:

Therefore, χ2 (df=1, n=120) is 4.84. The critical value of χ2 at α=0.05 (df=1) is 3.84. Thus, there is statistical evidence to support the argument that contribution of economic incentive to total household income is statistically significant at p<0.05.

Following the study findings that 61% of the total annual income of the household heads is accrued from practicing socio-economic incentives related activities, the Chi-square results released that the contribution of economic incentive to total household income is statistically significant at p<0.05. It is arguable that the adoption of socio-economic incentives can positively influence conservation initiatives due to the fact that the livelihoods of the majority of rural communities depends on available natural resources which presume high reliance of natural resources particularly the resources from the forest hence severe environmental degradation [42,46,47] However this study finding is contrary to what was reported by Lalika [42], who reported the adoption of socioeconomic incentives practiced by majority of communities in the general lands of Uluguru Mountains are not significant in enhancing livelihoods at the household level.

In line with this study finding, Scoones [48] postulates that livelihood strategies themselves must consist of combinations of activities which calls 'livelihood portfolios'. A portfolio may be highly specialized and concentrate on one or a few activities, or it may be quite diverse, so unravelling the factors behind a strategy combination is important. Moreover, different 'livelihood pathways' may be pursued over seasons and between years as well as over longer periods, such as between generations, and will depend on variations in options, the stage at which the household is in its domestic and indigenous cycle, or on more fundamental changes in local and external conditions. Livelihood strategies frequently vary between individuals and households depending on differences in asset ownership, income levels, gender, age and social or political status [49]. Basing on the study findings it is arguable that the adoption of economic incentives is useful towards influencing household livelihoods of the communities surrounding rehabilitated areas.

The study findings align the Lalika [42] findings on the application of socio-economic incentives in reducing the problem of biodiversity loss in Uluguru Mountains Forest Reserves, such that more or less the same roles revealed by this study were significantly played by the socio-economic incentives in the Uluguru Mountain Biodiversity Conservation Project (UMBCP) under Wildlife Conservation Society of Tanzania (WCST), Uluguru Mountain Agriculture Development Project (UMADEP) and the Morogoro Regional Catchment Forest Office towards carrying out biodiversity conservation activities in Uluguru Mountains [50-54]. The existence of HADO project in the study area imposed the same towards realizing the usefulness of the socio-economic incentives further than enhancing conservation initiatives.

Conclusion

This study was an attempt to reveal the less known contribution of socio-economic incentives the livelihoods of communities surrounding rehabilitated ecosystems. This study drew empirical evidences of Kondoa Rehabilitated Rural Areas (KRA), Dodoma, Tanzania. The study findings concluded that five socio-economic incentives were widely adopted by communities surrounding KRA namely; tree seedlings, fertilizer, improved seeds, beekeeping inputs and education and training programs. It was also concluded from the study findings that 61% of the total annual income of the heads of households in KRA being accrued from practicing the widely adopted socio-economic incentives [55-59].

This study finding implies high usefulness of socio-economic incentives towards enhancing household income and consequently resulting to positive outcomes to the livelihood activities prevailing in the area [60,61]. The fact that Chi-square test availed statistical evidence to support the argument that contribution of economic incentive to total household income is statistically significant at p<0.05, implies that by practicing socio-economic incentives in the particular household, 61% of the total annual income will be earned hence being a very useful intervention for improving household livelihoods while encouraging communities to sustainably conserve their surrounding biodiversity.

Recommendations

The following recommendations have been put forward based on the study findings and discussions presented hereinbefore:

a) The easily adopted five socio-economic incentives by communities surrounding KRA namely; tree seedlings, fertilizer, improved seeds, beekeeping inputs and education and training programs should be scaled-up to sustainably secure biodiversity available in many rehabilitated rural areas.

b) The revealed socio-economic incentives should be widely advocated conservationists, environmentalists and policy makers as very useful interventions towards improving household livelihoods while encouraging communities to sustainably conserve their surrounding biodiversity resources.

c) There is a need to capacitate the communities surrounding rehabilitated rural areas with an in-depth understanding of how to commercialize the applied socio-economic incentives so as to effectively improve their livelihoods [62-65].

Acknowledgement

I owe so much-and therefore am exceedingly grateful to my supervisor Professor John F Kessy of the Department of Forest Economics of Sokoine University of Agriculture for his outstanding guidance, advice, assistance, encouragement and constructive criticism throughout the preparation of this study and my entire Master Degree program at Sokoine University of Agriculture. I am highly indebted to all respondents in the study area but not limited to heads of households, Haubi and Kalamba Ward Executive Officers, Mafai, Ntomoko, Kalamba-Juu and Kalamba-Chini Village Executive Officers as well as Kondoa District Conservation Officers. Their cordial cooperation rendered to me during data collection is highly appreciated. However, my heartfelt gratitude is due to my lovely wife Mary and our son Ansbert for their passion and endurance during the time of undertaking of this study.

I am also indebted to the staffs from the Forest Economics Department who supported my learning tirelessly. The friendly and brotherly guidance, directives and courage from Prof. Ngaga YM, Prof. Abdalah JM, Dr. Lusambo LP, Dr. Mombo F, and Mr. Nyamoga GZ were very useful towards accomplishing my study [66-67]. Last but not least, the brotherly support from Prof. Dos Santos, S. and Mr. Kilawe, C. during the time of undertaking this study; their tireless efforts, energy, courage and inspiration including shaping my study theme and subsequently editing my questionnaires prior to field work data collection, to them I am indebted heartfelt appreciation.

References

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (2000) Using Economic Incentives for Biodiversity Conservation. Economics and Biodiversity Programme New York, USA, pp.198.

- McNeely JA (1992) Parks for life: Report of the 4th World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas. International Union for Conservation of Nature, Gland, Switzerland, p.53.

- Panayotou T (1994) Economic instruments for environmental management and sustainable development. Environment and Economics 6(4): 21-25.

- Adams W, Hulme D (2001) Conservation and community. African Wildlife and Livelihoods 14(4): 12-17.

- Guthiga PM (2008) Understanding local communities' perceptions of existing forest management regimes of a Kenyan rainforest. International Journal of Social Forestry 1(2): 145-166.

- Emerton L (2000) Using Economic Incentives for Biodiversity Conservation. Economics and Biodiversity Programme. World Conservation Union, Switzerland, pp. 299.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2004) Integrating Economic Development into Environmental Laws. Report on Legal and Institutional Issues in the Development and Harmonization of Laws Relating to Environment. New York, USA. pp.125.

- Monela GC (1995) Tropical Rainforest Deforestation: Biodiversity Benefit and Sustainable Land use: analysis of socio-economic and ecological aspects related to the Nguru Mountains, Tanzania. Thesis for Award of PhD Degree at Agricultural University of Norway, pp. 131.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2004) Environmental Management Act. Government Printers, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, p.18.

- United Republic of Tanzania (1994) Tanzania National Environment Action Plan First Step. Ministry of Tourism, Natural Resources and Environment, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, p.25.

- Christiansson C, Kikula IS (1996) Changing Environments Research on Man-Land Interrelations in Semi Arid Tanzania. Regional Soil Conservation Unit, Nairobi, Kenya, pp.876.

- United Republic of Tanzania (1998) National Forest Policy. Government Printers, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, p. 20.

- Kikula IS, Christiansson C, Mung'ong'o CG (1999) Man-Land Interrelations in Semi-Arid Environments of Tanzania. Dar es Salaam University Press, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, pp.321.

- Ligonja PJ, Shrestha RP (2013) Soil erosion assessment in Kondoa Eroded Area in Tanzania using universal soil loss equation, Geographic Information Systems and Socio-economic Approach. Land Degradation and Development 26(4): 367-379.

- Ogle RB (2001) The need for socio-economic and environmental indicators to monitor degraded ecosystem rehabilitation: a case study from Tanzania. Journal of Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment 87: 151-157.

- Kangalawe RYM (2003) Sustaining water resource use in the degraded environment of the Irangi Hills, central Tanzania. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 28(20-27): 879- 892.

- Shao FM (1999) Agricultural Research and Sustainable Agriculture in Semi-arid in Tanzania, in Sustainable Agriculture in Semiarid Tanzania. In Boesen J, Kikula IS, Maganga FP Dar es Salaam University Press, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, pp.15.

- Madulu NF (2001) Reversed migration trends in the Kondoa Eroded Areas: Lessons for future conservation activities in the HADO Project areas, Tanzania. Organization for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa 6(12): 21-28.

- Ostberg W (1985) A socio-economic study of the areas affected by the HADO-project, Tanzania. Social Anthropology 46: 581-598.

- Kangalawe RYM (2012) Food security and health in the southern highlands of Tanzania: A multidisciplinary approach to evaluate the impact of climate change and other stress factors. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 6(1): 50-66.

- Kangalawe RYM, Lyimo J (2010) Population dynamics, rural livelihoods and environmental degradation: Some experiences from Tanzania. Environment and Sustainable Development 12(6): 85-97.

- Mbegu AC, Mlenge WC (1984) Ten years of HADO 1973-1983. Forest Division, Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, pp. 18.

- Mbegu AC, Christianss C, Kikula IS (1996) The Problems of Soil Conservation and Rehabilitation Lessons from the HADO Project. In Changing Environments: Research on Man-Land Interrelations in Semi- Arid Tanzania. SIDA Regional Soil Conservation Unit, Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 23.

- United Republic of Tanzania (1982) The Local Government Laws of 1982 The Kondoa District Council By Laws Prevention of Soil Erosion, Land and Water Preservation and Care for Trees. Government Printers, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, pp. 19.

- CIFOR (2001) Income is not enough: The Effect of Economic Incentives on Forest Product Conservation. Center for International Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia, p. 57.

- Comerford E (2004) Choosing Between Incentive Mechanisms for Natural Resource Management: A Practical Guide for Regional Natural Resources Management Bodies. Department of Natural Resources. Mines and Energy, Brisbane, Australia, pp. 76.

- Matunga BN (2012) Moral economy: Ensuring food accessibility and changing food preference for vulnerable group in agro-pastoralist villages, central tanzania. Rural development policy and agro-pastoralism in east africa. In: Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Moral Economy of Africa. Fukui Prefectural University, pp. 25-29.

- Bryman A, Bell E (2011) Business Research Methods. (3rd Edn.) Oxford University Press, New York, USA, pp. 765.

- Njana MA (2008) Arborescent species diversity and stocking in Miombo woodland of Urumwa Forest Reserve and their contribution to livelihoods, Tabora, Tanzania. Dissertation for Award of MSc Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania, pp. 214.

- Giliba RA, Boon EK, Kayombo CJ, Chirenje LI, Musamba EB (2011) The influence of socio- economic factors on deforestation: A Case Study of the Bereku Forest Reserve in Tanzania. Journal of Biodiversity 2(1): 3139.

- Stiglitz J (1997) An Agenda for Development for the Twenty-First Century. 9th Annual Bank Conference On Development Economics. World Bank, Washington, USA, pp. 18.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2013) National Population Census 2012. National Bureau of Statistics, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, pp. 133.

- Ockiya AJF (2000) Socio-economic activities of women in artisanal fisheries of the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 1: 200-205.

- Adhikari B, Falco SD, Lovett JC (2003) Household characteristics and forest dependency: evidence from common property forest management in Nepal. Ecological Economics 48(2): 245-257.

- Kessy JF (1998) Conservation and Utilization of Natural Resources in the East Usambara Forest Reserves: Convectional Views and Local Perspectives. Tropical Forest Resource Management Wageningen Agricultural University, Netherlands, pp. 168.

- Maro RS (1995) In-situ conservation of natural vegetation for sustainable production in agro-pastoral system. A case study of Shinyanga, Tanzania. Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Management of Natural Resource and Sustainable Agriculture, Norway, pp. 119.

- Kamwenda GJ (1999) Analysis of Ngitili as a traditional silvopastoral technology among the Agro-pastoralists of Meatu, Shinyanga Tanzania. Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Sokoine University of Agriculture Morogoro, Tanzania, pp. 114.

- Ogle RB, Wiktorsson H, Masaoa P (1996) Environmentally sustainable intensive livestock systems in semiarid central Tanzania. In Christiansson C, Kikula IS Changing Environments: Research on Man- Land Interrelations in Semiarid Tanzania. Regional Soil Conservation Unit, Nairobi, Kenya, pp. 128-131.

- Abdallah JM, Sauer J (2007) Forest diversity, tobacco production and resource management in Tanzania. Forest Policy and Economics 9(5): 421-439.

- Kiwale AT (2002) Analysis of socio-economic determinants of afforestation and its impacts in semi-arid areas: Case study of Magu district Mwanza Tanzania. Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania, pp. 140.

- Butuyuyu J (2003) The impacts of economic incentives in afforestation activities in Same district, Kilimanjaro Regions, Tanzania. Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania, pp. 98.

- Lalika MCS (2006) The role of socio-economic Incentives on biodiversity conservation In general lands of Uluguru Mountains, Morogoro Tanzania. Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania, pp.117.

- Fischer FU (1993) Beekeeping in the Subsistence Economy of the Miombo Savanna Woodlands of South-Central Africa. Rural Development Forestry Network Paper No.2. Overseas Development Institute, London, pp. 1.2.

- Benabou R, Tirole J (2003) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Review of Economic Studies 70: 489-520.

- Ndomba CJ (2004) A socio-economic and ecological evaluation of Ruvu fuel wood pilot project, Kibaha, Tanzania. Dissertation for Award of MSc Degree at Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania, pp. 114.

- Lusambo LP (2009) Economics of Household Energy in Miombo woodlands of Eastern and Southern Tanzania. Thesis for Award of PhD Degree at University of Bangor, UK, pp. 493.

- Kajembe GC, Luoga EJ (1996) Socio-Economic Aspects of Tree Farming in Njombe District. Consultancy Report to the Natural Resource Conservation and Land-Use Management Project. Faculty of Forestry, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania, p.78.

- Scoones I (1998) Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis. International Development Studies, Brighton, UK, p.16.

- United Nations Development Programme (1997) Promoting Sustainable Livelihoods: A briefing note submitted to the Executive Committee. p. 58.

- Akankali JA, Chindah A (2011) Environmental, demographic and socio-economic factors influencing adoption of fisheries conservation measures in Niger Delta, Nigeria. Environmental and Earth Sciences 3(5): 578-586.

- Emerton L (1998) Why Wildlife Conservation Has Not Economically Benefited communities In Africa? Community Conservation in Africa. Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester, London, p. 25.

- Emerton L (1999) Community-based incentives for nature conservation. Biodiversity economics for Eastern Africa. International Union for Conservation of Nature Eastern Africa Regional Office.

- FAO (1987) Incentives for Community Involvement in Conservation Programmes. Conservation Guide, Food and Agriculture Organization Rome, Italy, pp.159.

- Kondoa District Councils (1990) Land Law on Small Terrestrial Prevention, Land Storage and Water Management and Tree Care.

- Kangalawe RYM, Liwenga ET, Masao CA (2012) Biodiversity conservation in Central Tanzania. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment 162: 90100.

- Kowero GS, O'Kting'ati A (1990) Production and trade in products from Tanzania's natural forests. Faculty of Forestry Record 43: 102-106.

- Mendoza CC (2006) Factors influencing participation in environmental stewardship programs: A case study of the Agricultural and forestry sectors in Louisiana. Thesis for Award of PhD Degree at Dissertation, Louisiana State University, USA, pp. 10-25.

- Ndanga JP (2012) Household economy of the Wagogo: Contribution of income diversification in income poverty reduction to smallholder farmers in Dodoma-Tanzania. Rural development policy and agro- pastoralism in East Africa. In: Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Moral Economy of Africa. Fukui Prefectural University, pp.1-15.

- Pallant J (2005) SPSS Survival Manual 2nd Edition: A step by Step guide to data analysis using SPSS for windows (Version 12). Open University Press, Berkshire, UK, pp. 160-168.

- Saha G (2011) Applying Logistic Regression Model to the Examination Results Data. Reliability and Statistical Studies 4(2): 105-117.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2008) Harmonization and Development of Environmental Laws. Report on Legal and Institutional Issues in the Development and Harmonization of Laws Relating to Wildlife Management. New York, USA, pp. 170

- United Republic of Tanzania (1997) National Environmental Policy. Government Printers, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, pp. 18.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2003) National Population Census 2002. National Bureau of Statistics, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, pp. 122.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2007) National Sample Census of Agriculture 2002/2003. Regional report, Morogoro Region, Ecoprint. Morogoro, Tanzania, pp.370.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2010) Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2015-2016. Government Printers, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, pp.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2011) National strategy for growth and reduction of poverty and human development, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Whitehead J (1998) Willingness to Pay For Bass Fishing Trips In Carolinas. (3rd Edn.), Carolina University Press, USA, pp. 56.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...