Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2643-6760

Research Article(ISSN: 2643-6760)

Veinous Thromboembolism in Hospital University of Gynecology and Obstetric Befelatanana Volume 3 - Issue 4

T Razafindrainibe1, S Rakotonomenjanahary2*, TP Randrianambinina3, AT Rafanomezantsoa3, M Andrianirina1, L Rainibarijaona1 and AT Rajaonera4

- 1Adult Intensive care Unit, CHU-GOB, Antananarivo, Madagascar

- 2Anesthesiology Unit, CHU-JDR, Antananarivo, Madagascar

- 3Anesthesiology Unit, CHU de Tamatave, Antananarivo, Madagascar

- 4Surgical Resuscitation Unit, CHU-JRA, Antananarivo, Madagascar

Received: October 16, 2019; Published: October 24, 2019

Corresponding author: S Rakotonomenjanahary, Anesthesiology Unit, CHU-JDR, Antananarivo, Madagascar

DOI: 10.32474/SCSOAJ.2019.03.000167

Abstract

Introduction: In three studies done in Madagascar, venous thromboembolism mainly affects the female gender. The objective of this study was to identify the characteristics of this disease at Hospital University of Gynecology and Obstetrics Befelatanana.

Methods: This is a retrospective descriptive study for four years, from January 2011 to December 2014.

Results: We identified twenty-seven veinous thromboembolism in 42 443 cases (0.06%) of which 15 cases (55%) of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 8 cases (30%) of pulmonary embolism and 4 cases (15%) of deep vein thrombosis complicated by pulmonary embolism. The average age is 37.74 years. The main risk factors are age over 40 years (40.74%), postpartum (40.74%), prolonged immobilization (25.92%), gynecological cancer (18.51%), pregnancy (18.51%) and menopause (14.81%). All patients with DVT suffer from unilateral lower limb pain and dyspnea for pulmonary embolism. Enoxaparin relaying by fluindione earlier is our main cure, and enoxaparin associated with early up constitute preventive treatment. Eleven cases have a favorable outcome. Ten cases died of pulmonary embolism. The rest has been transferred into specialized services.

Conclusion: The search for risk factors of thromboembolism is the basis of prevention.

Keywords: Anticoagulant; Epidemiology; Evolution; Female; Risk Factor; Venous Thromboembolism; Prevention

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a unique pathology that includes two main clinical forms: deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). The risk factors for the occurrence of VTE are multiple and often related to hospitalization. Apart from all the other factors common to both genders, the woman has particular risk factors such as contraception, pregnancy, postpartum, uterine myoma, gynecological and obstetrical surgery, hormone replacement therapy, protocols ovulation stimulation in the context of medically assisted procreation [1]. Through its impact on morbidity and mortality and medical costs, VTE represents a major public health issue. The incidence of DVT and PE in the general population is respectively about 1 case per 1000 people per year and 0.5 / 1000 people / year [2]. In Madagascar, three studies were conducted in three different departments that found an incidence of VTE ranging from 0.07% to 0.97% [3-5]. All these studies found a female predominance. The main objective of this study is to determine the characteristics of the VTE in the University Hospital of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Befelatanana (CHU GOB).

Method

It is a retrospective descriptive study carried out over a fouryear period (January 2011 to December 2014), at the University Hospital Center of Gynecology and Obstetrics in Befelatanana (CHUGOB). Included in this study are all patients hospitalized at CHU GOB and presenting with clinical signs of DVT MI and / or PE, with a high or intermediate clinical probability score for PE. Excludes low clinical suspicion of PE or presence of diagnosis other than PE and incomplete, unusable sources. The parameters studied in this study are sociodemographic parameters, anamnestic parameters, clinical parameters, paraclinical parameters, the principles of management and evolution. The results obtained were copied to Microsoft Excel and then processed on the XLS 6.0 software. They were expressed on average and as a percentage.

Results

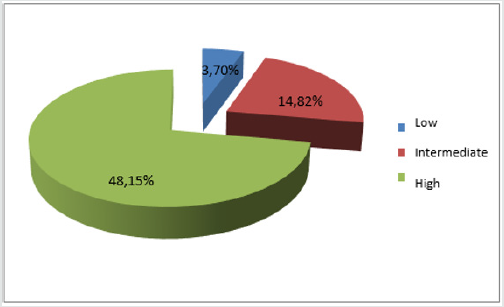

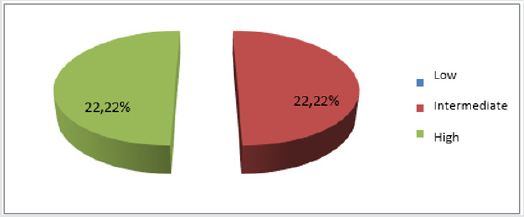

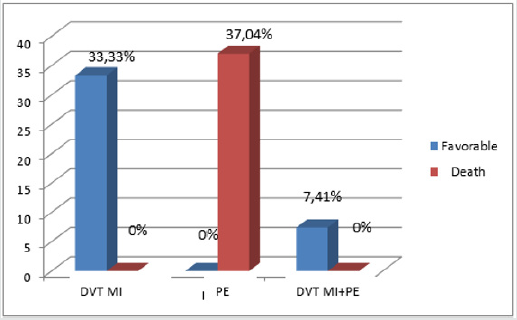

There were 42,443 patients hospitalized at the University Hospital of Gynecology and Obstetrics Befelatanana from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2014. Twenty-seven of them had been identified as having presented an MTEV or 0.06% of which: 15 cases (55%) of TVPMI, 8 cases (i.e. 30%) of PE and 4 cases (15%) of TVPMI complicated with PE. The mean age of the patients was 37.74 years with a standard deviation of 11.86 years; the extreme ages were 18 and 63 years old. Patients between the age group 20 - 30 years were the most numerous with 9 cases or 33.33%. Patients with 3 and 4 parities were the most numerous with 11 cases (40.74%) of each. Among the reasons for hospitalization, metrorrhagia ranked first with 10 cases (37.04%), followed by pelvic pain and infectious syndrome with 04 cases each (14.82%), followed by dyspnea. 03 cases (i.e. 11.11%), and finally the pain of the lower limbs with 02 cases (i.e. 7.41%) Post-partum, menopause, gynecological cancer, pregnancy was the most frequently encountered gynecological and obstetric risk factors with a frequency ranging from 14.81% to 40.74%. For post-partum, 63.63% (7 out of 11 cases) of MTEV occurred after cesarean section and 36.37% (4 cases out of 11) after vaginal delivery. Age greater than or equal to 40 years, bed rest, heart failure and sedentary lifestyle were the most frequently encountered medical risk factors accounting respectively for 40.74% of cases (11 cases); 25.63% of cases (7 cases) and 14.82% of cases (4 cases) for the remains. Patients with only one risk factor were the most numerous with 33.33% of cases (9 cases). The 17 cases (62.97%) have at least two risk factors. Clinically, out of twenty-seven cases, 19 (70.37%) had lower limb pain at the time of diagnosis, followed by the positive HOMANS sign and unilateral MI edema accounting for 51.85% (14cas) and 48.15% (13 cases). In contrast, tachycardia and dyspnea were the most representative signs of PE with 12 cases (44.44%) of each followed by chest pain and signs of shock in 6 cases (22.22%). Finally, by hemoptysis with 4 cases (14.81%). In the case of TVPMI, according to the WELLS score, 48.15% of our patients (13 cases) had a high probability; 14.81% (i.e. 4 cases) a moderate probability and 3.70% (i.e. 1 case) a low clinical probability of TVPMI (Figure 1). According to the same score, the same frequency of 22.22% (12 cases) represented the strong and moderate clinical probability of PE (Figure 2). The MTEV sat on the lower left side in 37.04% of cases (10 cases), in the lower right in 33.33% of cases (9 cases). Isolated pulmonary embolism accounted for 29.63% (8 cases). Paraclinically, only three out of twenty-seven patients (11.11%) were able to assay the D-Dimer whose value was greater than 500μg / ml. Fifteen patients out of 19 cases (i.e. 79%) of TVPMI were able to do Doppler ultrasound of the lower limbs. Of the 15 patients who underwent ultrasound Doppler ultrasound, the iliac vein was the most affected with 6 cases (40%), followed by the femoral vein and popliteal under popliteal with 4 cases of each (26.67%). In terms of treatment, eight cases (29.63%) benefited from drug thromboprophylaxis with LMWH and early levee before the MTEV episode. Note that they were all post-operated. Twenty-two out of twenty-seven cases (81.48%) received curative doses of LMWH, of which only 14 cases (or 51.85%) had been relayed to the AVK. No patients received fibrinolytics or UFH. Ten cases (37.04%) required respiratory support and vasopressors. Regarding evolution (Figure 3), eleven cases (40.74%) had a favorable evolution; while 10 patients (37.04%) died and 6 (22.22%) transferred to a specialized department.

Discussion

In developed countries, the frequency of VTE was around 85 to 180 per 100,000 women per year [6-7]. In Africa, hospital prevalences ranged from 1.88% to 11.76% [1,8 -9]. In Madagascar, at the Soavinandriana Hospital Center, the frequency was 0.07% in 2007 [4] and 0.97% in 2014 at the Joseph Ravoahangy Andrianavalona University Hospital [5]. In our study, the prevalence of VTE was 6/10,000 women per year. This low incidence would probably come from an underestimation of the disease, the mode of recruitment, which is only concerned with symptomatic venous thromboembolic diseases, but especially because the CHUGOB is attended only by women with gynecological pathologies and or obstetric. Indeed, according to the literature, asymptomatic forms of MTEV constitute 15.8% to 50% of cases [10,11]. The mean age of the patients was 37.74 years with a standard deviation of 11.86 and the extreme ages were 18 and 63 years respectively. Fifty-six percent of our patients were in the 20 to 30 age group. This could be explained by the fact that this age group corresponds to the period of maximum genital activity is therefore to the association of thromboembolic events: pregnancy, the postpartum period and the use of oral contraception. In this age group, the incidence of VTE is estimated to be less than 0.2 / 1000 women per year among those under 20; 0.3 / 1000 women per year aged 20 to 30; 0.45 / 1,000 women per year aged 30 to 45 years [12]. According to Naess IA et al, the incidence of MTEV is higher in women than men before age 50 [13]. In developed countries, patients with the disease had a higher average age at age 65 [14,15]. Metrorrhagia was in first place with 10 cases, or 37%, half of which was related to gynecological cancers. Venous thromboembolism in many studies is secondary to active cancers. According to Esmon CT, cancer increases the thromboembolic risk by 6 to 10 times [16]. The highest risk cancers of VTE are those of the pancreas, stomach, genitourinary tract, lung, colon and breast [16]. In Algeria, one-third of cancer patients developed thromboses [8]. In Uganda, Andrew L et al. have found that, apart from surgery, cancer is the factor most associated with thrombosis [17]. In Madagascar the frequency of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer is not known. Our study therefore participates in the constitution of a database in this sense. In Raveloson’s study, lower limb pain is the most observed pattern. This pattern is followed by unilateral edema of MIs in the case of TVPMI, dyspnea and chest pain for pulmonary embolism [3]. Thus, VTE is the reason for hospitalization in their studies. In our study, 77.78% of our patients are referred by other practitioners and / or care institutions in the Gob CHU for gynecological and obstetric reasons. Either they are referred for metrorrhagia related to cancer, or for pelvic pain related to work. Only two cases, 7.41%, were admitted for suspicion of thrombophlebitis associated with pregnancy and three cases for postpartum dyspnea. Thus, in our study, VTE is a pathology strongly related to hospitalization. As for risk factors, according to the literature, pregnancy in itself represents a period when the thrombotic risk is increased by physiological disturbances: tendency to hypercoagulability linked on the one hand to mechanical factors and on the other hand partly to biological modifications [12]. The risk analysis of MTEV made by Gris JC et al. Showed a low rate during the first trimester of pregnancy, a doubled risk in the second trimester and a sixfold increase in the risk during the third trimester [18]. In our study, the risk factor represented by pregnancy is found in 18.51% of cases, of which 40% were in the first and third trimester and 20% in the second trimester of pregnancy. This discrepancy can be explained by the low number of samples. In a Korean PAPE study (Pregnancy- Associated PulmonaryEmbolism), all cases of pulmonary embolism occurred in the postpartum period after caesarean section [12].

In Sudan, the risk of thrombosis during the postpartum period is 94% [17]. In our study, the postpartum period was found in first place with a rate of 40.74% of which 63.63% after caesarean section and 36.37% after vaginal delivery. Estrogen / progestin contraception is one of the risk factors with high thrombogenic potential [19]. It increases the risk of venous thrombosis by five [20,21]. In our study, oral contraception is one of the risk factors for VTE because it is found in 11.11% of cases. This result is close to that found by Raveloson et al. [3]. Patients with heart failure are older and may be immobilized for a period of time [22]. According to the literature, the discovery of heart failure increases the risk of VTE by up to 15 to 30% [23]. According to a study of MTEV and pregnancy performed in Benin, the incidence of heart failure as a risk factor is 3.9% [1]. In our study, heart failure is found in 15% of cases as the literature describes it. In our study, one case in twenty-seven (3.7%) had a personal history of VTE whose seniority compared to the first incident was not reported in medical observation. This rate is much lower than the results found by Kingue et al. and by Nourelhoud et al, which are respectively 16.7% and 12% [19,24]. This difference can only be explained by the underestimation of the illness or by her lack of knowledge of her illness. VTE is a multifactorial pathology involving constitutional, acquired and environmental risk factors [25,26]. According to the literature, almost 80% of hospitalized patients have at least one risk factor for VTE, 50% have at least two risk factors [25]. This result is close to ours, which is 62.96%. Clinically, Raveloson et al. proposed that the Wells score with medium or high clinical probability, with or without a positive D-Dimer, is sufficient to establish the diagnosis of VTE [3]. In our study 59, 26% of our patients have high clinical probability scores; 37.03% intermediate and 3.7% weak. In our study, MTEV is located mainly in the lower limbs in 19 patients (70.37%), with slightly higher involvement of the lower left limb in 10 cases or 37.04%. The preferred location of MTEV is on the lower left limb. This predilection is due to the compression of the left primary iliac vein by the right primary iliac artery and the gravid uterus. Paraclinically, in our study, 89% of the patients could not do the dosage of D-Dimers because of insufficient financial means, the impossibility of carrying out this test within the same establishment. However, this examination has a high negative predictive value that can quickly eliminate ambiguous forms. Ultrasound is a non-invasive examination that is widely available within CHUGOB where our study was conducted. Unfortunately, venous ultrasound is not available to all and the technicians who work there do not practice this examination. Thus, only 80% of our patients experienced it by performing it outside the establishment. CT angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of PE because its sensitivity and specificity are high, ranging from 64 to 100% and 89 to 100%, respectively [22]. However, this examination is financially inaccessible to the majority of patients from which no patient has benefited. As for the treatment, for the prevention, in our study the preventive means are indicated for the patients who had undergone a cesarean operation. These means are mainly the early and routine administration of enoxaparin 0.4 ml subcutaneously at the sixth hour postoperatively and for 48 hours [27]. Note that the elevation of the members and the BAT have not been used as a means of prevention because the cost of the latter is too high and therefore not within the reach of patients admitted to CHUGOB. But despite this preventive treatment, of the 10 cases, 37%; 8 cases developed DVT and 2 cases fatal pulmonary embolism. The explanation is that the prevention modalities were completely unsatisfactory and / or unsuitable. Indeed, for lack of diagnosis (lack of imagery and biology) the curative treatment for the 2 deceased cases could not be started. And as for the curative treatment of MTEV, it is mainly based on anticoagulants. The recommendation consists of two stages: heparin treatment and early releasing with vitamin K antagonists (AVK). Heparin treatment will be continued for one week to 10 days because of the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and until an INR is obtained in the therapeutic zone (between 2 and 3) in two consecutive samples at 48 hours. intervals [27,28].

Other treatments include treatment of the contributing factors, symptomatic treatment (analgesic, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug, oxygen therapy), strict bed rest at the beginning of anticoagulant treatment and education of patients and their families [3]. During our study, 81% of the patients were able to benefit from enoxaparin but only 52% of them were relayed by AVK, considering the state of pregnancy which against the AVK, some of our patients died after that the diagnosis be made and that the heparinotherapy is established and lack of financial means for the purchase of medication and the achievement of monitoring report. This same problem is often encountered in other developing countries of Africa [29,24]. Regarding the evolution, according to the literature, the mortality and morbidity of venous thromboembolism are directly correlated with the speed of its diagnosis and its therapeutic management. Mortality drops significantly if diagnosis and treatment begin promptly [29]. A study by Julien Lefèvre on the epidemiology of maternal mortality in hospitals found a mortality rate of 11.11% for all cases, a maternal mortality rate of 2.3 per 100,000 births. In the United States, one third of deaths from pulmonary embolism occur within one hour of the first symptoms. The mortality rate among hospitalized patients during the first episode is 12%; the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is not suspected in more than 70% of patients who died [30]. In our study, the mortality rate represents 10 out of 27 cases (37%). They are all related to PE. In 8 out of 10 cases (30%), death occurred in the postpartum period and in 2 cases by complicating a gynecological cancer. There is a great discrepancy between the results announced by the literature and ours. The possible explanation for this discrepancy may be our ability to label the diagnosis of death as pulmonary embolism without any radiological or biological support or post-mortem examination being performed. These same problems are found by other authors in developing countries [3,9].

Conclusion

Thromboembolic disease is a unique pathology involving the cardiologist, resuscitator, gynecologist, obstetrician, oncologist, neurologist, ... The female predominance of MTEV in Malagasy studies gave the inspiration for this study. So, his goal was to determine the characteristics of this disease at the Gob Hospital. During a four-year period (from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2014), 42,443 patients had been hospitalized at the University Hospital Center of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Befelatanana. Twenty-seven of them were identified as having a VTE or 0.06% and in 15 cases (55%) it was TVPMI, 8 cases (or 30%) PE and 4 cases (either 15%) of TVPMI complicated with EP. Age greater than 40 years, menopause, prolonged immobilization, gynecological cancer, pregnancy were the most frequently identified risk factors. The knowledge of these factors added to the clinical probability score is a major aid in the diagnosis and management of patients. The practice of preventive measures in this study only concerns post-caesarized patients. However, ten out of twenty-seven cases died by MTEV including eight cases in postpartum and two cases following cancer. These results should contribute to improving the management of the disease through a systematic assessment of risk factors, a well-conducted clinical approach, a provision of diagnostic and surveillance equipment, the establishment of prevention in patients at risk and training of health personnel.

References

- Dénakpo JL, Zoumènou E, Kérékou A, Dossou F, Hounton N, et al. (2012) Frequency and risk factors of venous thromboembolism in women in hospitals in Cotonou, Benin. Clinics in Mother and Child Health 9: 5.

- Motte S (2009) Venous thromboembolism and superficial vein thrombosis. Vascular Pathology Department Erasmus Hospital, Brussels. Specific training SSPF.

- Raveloson NE, Vololontiana MD, Rakotoarivony ST, Razafindratafika ACF, N Rabearivony N, et al. (2011) Epidemiological and progressive aspects of venous thromboembolic diseases in the Cardiology Unit of the University Hospital of Antananarivo. Rev Anes Réa Med Urg 3(1): 35-39.

- Razafindrakopy MA (2007) Venous thromboembolism at the Soavinandrina Antananarivo Hospital Center (About 24 cases observed) [Thesis]. Human Medicine: Mahajanga, p. 63.

- Raelison JG (2014) Venous Thromboembolism in Surgical Resuscitation at Joseph Ravoahangy University Hospital Andrianavalona [Thesis]. Human Medicine: Antananarivo, p. 50.

- Julien L (2014) Epidemiology of maternal hospital mortality. Observational study conducted in Reunion [Thesis]. General Medicine: Bordeaux 2: 93.

- Magdalena J, Lars J, Marcus L (2014) Incidence of venous thromboembolism in Northern Sweden (VEINS): a population-based study. Thromb J 12: 16.

- Bensahla TMH, Zahdour A, Djilali L, Hadj KS, Dubourdeau P, et al. (2012) Particularity of the support of the MTEV in Algeria. Clinical Fellowship: GFTC.

- Martin H (2012) Venous Thromboembolism in Sub-Saharan Africa, Frequency and Profile of Patients. Session of the Tropical Cardiology Group of the SFC. Paris.

- Marie AS (2010) Update of epidemiological models and application to venous thromboembolism. Life Sciences. Joseph Fourier University - Grenoble I.

- Massondi M (2007) Venous Thromboembolic Disease, Season Meteorology and El Nino Phenomenon. Online memory.

- Aurélien D, Emmanuelle LM, Dominique M (2011) Risk of venous thromboembolism in women of childbearing age. Med Ther 17(3).

- Naess I, Chistiansen SC, Romundstad P, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, et al. (2007) Incidence and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost 5: 692-699.

- Abbadi MA (2015) Pulmonary Embolism (About 40 cases) [Thesis]. Human Medicine: Sidi 81p.

- Mean M, Aujesky D (2009) Thromboembolic disease in the elderly. Rev Med Switzerland 5: 2142-2146.

- Claude J (2006) Epidemiology and risk factors for venous thromboembolism in elderly patients. Blood Thromb Vaiss 18: 22-26.

- Andrew LM, Moses G, M Patson, Tom M, Faith A, et al. (2013) Deep venous thrombosis after major surgery in Ugandan hospital: a prospective study. Int J Emerg Med 6: 43.

- Gray J-C, Quéré I, Dauzat M (2012) Prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy. J Mal Vasc 12: 137.

- Nourelhuda C, Demmouche A (2013) Venous thromboembolic disease in the region of Sidi Bel Abbes, Algeria: frequency and risk factors. Pan Afr Med J 16: 45.

- Plu-Bureau G, Horellou MH, Gompel A, Conard J (2008) Hormonal Contraception and Venous Thromboembolic Risk: When to Request a Study of Hemostasis? And which one? Gyn Obst & Fert 36: 448-454.

- Hylckama V, Helmerhorst FM, Vandenbroucke JP, Doggen CJM, Rosendaal FR (2009) The venous thrombotic risk of oral contraceptives, effects of estrogen dose and progestogen type: results of the MEGA case-control study. BMJ 339: b2921.

- Zidi A, Belhiba H, Hantous-Zannad S, Mestiri I, Baccouche I, et al. (2008) Inflammation of thoracic angio-CT scan in patients suspected of pulmonary embolism. Abderrahmane Mami Ariana Hospital.

- Imberti D, Pierfranceschi MG, Falcian M, Prisco D (2008) Venous Thrombosis Embolism prevention in patients with heart failure: an often neglected. Pathophisiol Haemost Thromb 36: 69-74.

- Kingue S, Tagny DZ, Binam F, Novedov CI, Teyang A, et al. (2002) Venous thromboembolism in Cameroon about 18 cases. Med Trop 62(1): 47-50.

- Delluc A, The Ven F, Mottier D, The Gal G (2012) Epidemiology and risk factors for thromboembolic venous disease. Rev Mal Resp 29: 254-266.

- Rouf S (2015) Deep vein thrombosis: experience of the Oujda Hospital Internal Medicine department (About 136 cases) [Thesis]. Human Medicine: Sidi p. 82.

- Lemiengre M, Vanhee L (2005) What is the most effective D-dimer test for excluding DVT or pulmonary embolism? Minerva 4(4): 58-60

- (2008) National College of Teachers of Internal Medicine. Prescription of anti-thrombotic treatment. Ellipses, pp. 177-186.

- Sangar I, Menta I, Ba HO, Fofana CA, Sidib N, et al. (2015) Thrombophlebitis of limbs in the cardiology department of CHU Gabriel Toure. Mali Med XXX: 1.

- Johanne Roy (2009) Pulmonary embolism. Rev Ord Prof Inh Quebec 26(1).

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...