Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Measuring Student Engagement In A High School Context Volume 6 - Issue 1

Manoj Nair*

- Department of psychology, University of Tasmania, Churchill Ave, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Received:November 01, 2021; Published:December 01, 2021

Corresponding author: Manoj Nair, Department of psychology, University of Tasmania, Churchill Ave, Hobart, TAS, Australia

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2021.06.000229

Abstract

The topic of student engagement is of considerable interest among researchers, practitioners and policymakers in education owing to its high correlation with academic achievement and school completion [1-5], mental health [6,8], and unproductive behaviour in schools [9-12]. Also, engagement as a multidimensional and interdisciplinary construct appears to offer a richer insight into how students think (cognition), act (behaviour), and feel (affect) at school than research on any other single dimension [13-17].

Introduction

Furthermore, student engagement has important policy

implications, especially in an Australian high school context

where securing a high Year 12 attainment rate has been cited as

an important objective [5,9,11], professed to be closely linked to

developing national productivity and increasing human capital

[19-21]. Notably, over 25% of young people across Australia (and

over 40% in the state of Tasmania) do not complete Year 12 or

its equivalent [22], with over one-third being stressed about high

school [23], and over 40% disengaging from learning in high

schools [24].

Thus, educators (teachers, senior school staff) continuously

devising interventions to promote engagement in high schools

[25-27]. However, addressing low student engagement appears

to be a significant contributor to teacher stress and burnout since

it occupies most of their planning and teaching time and hinders

their ability to teach effectively [15,19,20]. Additionally, educators

often struggle to understand why and how much their students are

engaged, or otherwise, in school [28-31]. Consequently, they often

rely, somewhat inaccurately, on their intuition or inferences (from

observation and experiences) or readily available behavioural

data or student demographics to inform and design interventions

that promote student engagement in their schools [32-34]. As a

result, wide variations are noticed in the practices followed and

the outcomes achieved in different high schools [30]. Given that

student engagement has the potential to address the significant

issue of low educational attainment in high schools [35,36], it

is imperative to find a systematic (replicable) way of measuring

student engagement to better inform the interventions that

promote it. The first and essential step in managing something well

is to measure it accurately [37].

Thus, to promote students’ engagement sustainably through

relevant interventions, so they stay productive and longer in

schools [38], we need to start by finding a systematic way to

measure it. However, it is easier said than done, since the topic

of engagement, in addition to being a relatively new one (first

appearing in literature in the 1980s), appears to be a latent and

complex metaconstruct [39-42]. Thus, there might be some pending

clarifications regarding theoretical underpinnings, definition,

attribution, factorisation, data collection and interpretation, and

therefore measurement surrounding the topic of engagement. So,

the purpose of this document is to provide such clarifications (when

needed) by undertaking a literature review. Furthermore, this

document concludes by offering a considered view on the inquiry

question-is there a valid and reliable way for educators to measure

latent psychological constructs such as student engagement in a

high school context?

Beginning with the exploration of the influential theories that

inform the definition of engagement, it would appear that there

are three prominent ones: the participation- identification model,

the self-system motivational model, and the person-environment

perspective [43]. The participation-identification model explains

the interdependent and cyclical relation of a student’s participation

in school activities (behavioural engagement) with the value

attached to the school (emotional engagement) [44,45]. The selfsystem

motivational model illustrates how the classroom context

(i.e., structure, autonomy, support, and involvement) influences

the students’ action (cognitive, behavioural, and emotional

engagement) through the mediation of students’ self-system

processes (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) [46-50]. The

person-environment perspective connects students’ engagement

to the fit between their needs and goals and the opportunities provided by their environment to meet them [25,26]. Together, the

theories help to build a conceptual framework on engagement that

integrates the personal (self), family (or home), social (peers), and

other environmental (teachers, school) factors that might influence

it [51-54].

Now, there have been as many as nineteen different definitions

of engagement due to the variations in the scholarly interpretations

of the concept between 1985 and 2008 [55]. Subsequentially, there

have been attempts to arrive at a standard [55-58].

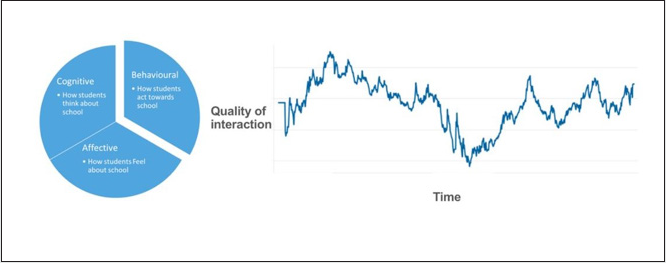

An acceptable and comprehensive definition of student

engagement appears to include three essential aspects:

1) engagement as a relationship that students have with

education (teachers, classrooms, learning resources, schools,

etc.) [59-61];

2) engagement as multidimensional-comprising of the three

interrelated dimensions of cognition, affect or emotion, and

behaviour [62-65] and

3) engagement as a process in constant flux (malleablestrengthening

and weakening depending on the quality of

interactions that the student has with education over time)

[65,66] as outlined in Figure 1.

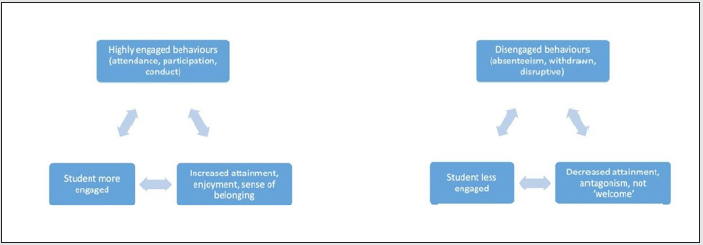

Furthermore explain engagement as both a psychological state and a behaviour, and ever since the seminal work of Finn and the causal link between affective and cognitive engagement with behavioural engagement has been made clear – put simply, if a student feels safe and emotionally connected to a school, and is able and interested in the work, he or she is more likely to participate effectively in the learning program [67-69], as outline in Figure 2.However, to accurately attribute the impact of engagement, it is essential to distinguish between its dimensions, influencers, and manifestations [70]. Influencers are what cause student engagement to fluctuate in the school context–they could be student-related [51,47,55], or school and teacher-related [28] or family and peer support related [35]. On the other hand, manifestations such as academic performance and educational attainment result from students engaging in schools [71]. Often, schools include easily observable behavioural engagement dimensions such as attendance or truancy (unexplained absences) as manifestations for conceiving the interventions to improve them.

However, such an approach can be problematic since it makes

it difficult to ascertain the effects of the engagement dimensions

on its manifestations [72]. Also, engagement might need to be

conceptualised and measured separately from disengagement

or disaffection [34,38,41]. Additionally, it is essential to clarify

the relationship between motivation and engagement in that the

latter represents the action (behavioural) or interest (cognitive)

component of the former [73,74]. Thus, with such clarifications on

proper attribution, attempts have been made to measure student

engagement [25].

There are several ways to collect data on student engagement–

from student self-report surveys to the use of teacher ratings,

interviews and focus groups, observational methods, administrative

data, and even technology-aided real-time measures [75]. Student

self-report surveys appear to help understand the latent cognitive

and affective dimensions of engagement that are not readily

observable in high school students [76]. Furthermore, the other

methods suffer from either observer or reporter bias [58-61], or

issues of validity and reliability [77-79], or may be obtrusive, timeconsuming

and expensive [11,17,24]. Notably, student self-reported

engagement predicts high school completion (or dropouts)

significantly better than other easily observable and commonly

used behavioural data such as attendance (unexplained absences)

or academic achievement data [33,37,38].

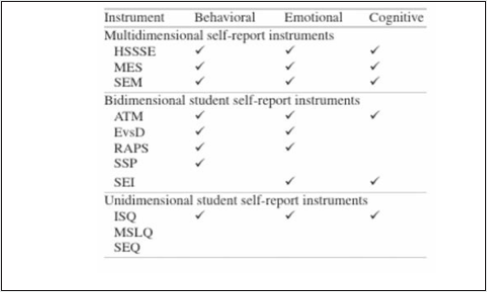

An extensive review conducted by comparing and contrasting

eleven student self-reported survey measures, appears to

provide critical insights into the various attempts (methods

and instruments) to attribute, factorise and measure student

engagement. A closer look at the survey measures, as listed in

Figure 3, indicate differences in purpose. Some surveys explicitly

assessed engagement, while others related constructs such as

identification with school, motivation, self-regulation, and strategy

use as measures of engagement. Some surveys measured general

engagement, whereas others, class or subject- specific engagement.

The survey measures also varied on whether and how they have treated disengagement in relation to engagement. For example, while some have represented disengagement as the opposite of engagement [17], others have attributed the former to lack of the latter [28]. Also, the surveys differed on whether they addressed each of the three dimensions of engagement, as seen in Figure 4. Each of the surveys measured factors of engagement by representing them as subscales. Eight surveys contained factors that seemed to reflect (either by the factor name or the sample items) aspects of behavioural engagement. At the same time, six of them addressed cognitive engagement and eight of them parts of emotional engagement, as outlined in Figure 5.

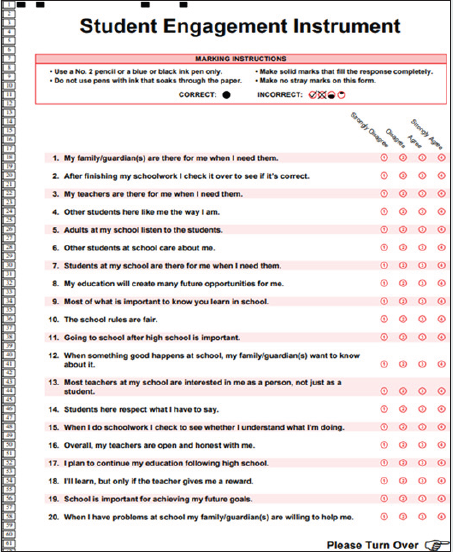

Additionally, the survey instruments themselves varied; from

the Engagement versus Disaffection scale that tested the students’

self-system model of engagement [15,18] to the Student Engagement

Measure (SEM) that assessed the relationship between context and

engagement [34]. Of specific interest in this document are two

surveys that had the explicit purpose of improving educational

attainment rates (by reducing school dropouts or ensuring school

completion) -the Identification with School (ISQ) questionnaire

and the Student Engagement Instrument (SEI).

While the ISQ (rooted in the participation-identification model)

assessed the extent to which students identified with school and

used it as a measure of engagement [22], the SEI measured the

latent cognitive and affective dimensions of engagement and

used them to expand on the more observable behavioural and

academic indicators that were collected and reported by schools

routinely [24]. Significantly, the SEI integrated the leading

influencers of engagement (espoused by the three prominent

theories underpinning it), such as motivation, autonomy, school,

and environment within the scales measuring engagement, thereby

treating engagement appropriately as a mediator between its

influencers and its outcomes [32]. Also, being a quantitative measure

that could be deployed as a measurement tool from time to time,

the SEI (just like the other ten measures) recognises the inherent

malleability of the engagement construct [44]. Furthermore, each

instrument was evaluated for its reliability (its ability to produce

similar results across contexts) and validity (the extent to which

it measures what it claims to measure), and the SEI instrument

scored the highest in reliability scores [55], as seen in Figure 6.

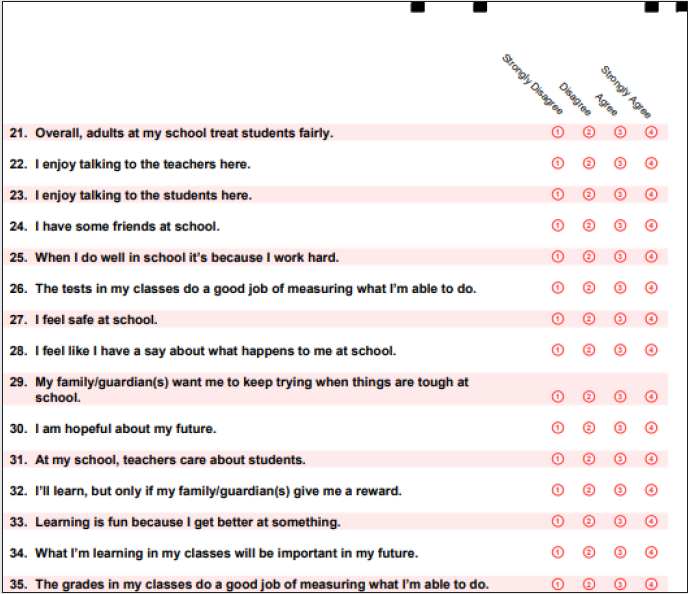

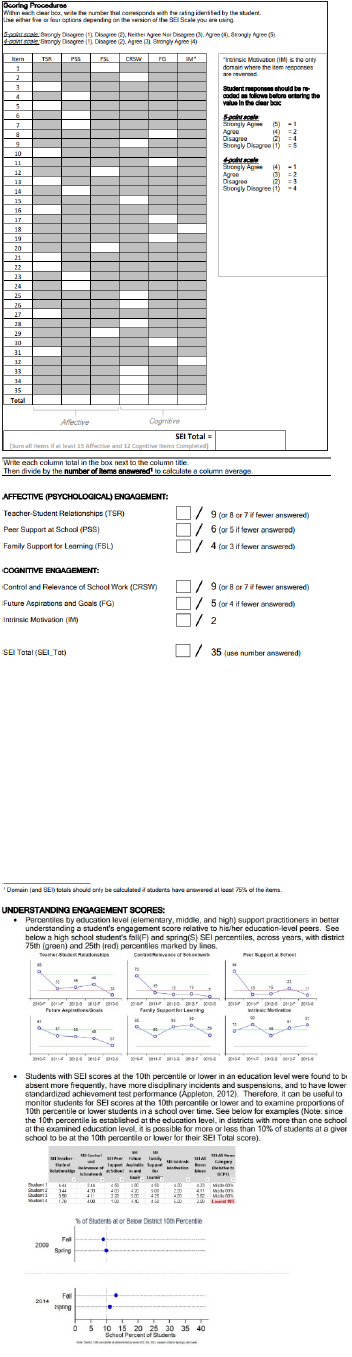

The validities of the survey instruments were assessed using different approaches such as construct validity and criterion-related validity [46]. However, the validity results were not compared due to the significant variations in the type and number of factors and items considered in the eleven surveys. The SEI instrument scale used exploratory factor analysis for assessing construct validity on fifty-six items using a socially and culturally diverse sample of 1931 ninth graders and was found to be valid, with the emergence of six subscales (teacher-student relationships, peer support, family support, control and relevance of schoolwork, future aspirations, and extrinsic motivation) [11-14]. Further attempts at refining the SEI instrument using confirmatory factor analysis resulted in five subscales, dropping extrinsic motivation as a subscale [36]. Over time, the SEI instrument has been refined to improve its validity and reliability further, concurrently with behavioural engagement measures [58], across some teaching and learning contexts [44], and across some geographies [17]. In its current form, the SEI comprises 35 student self- reported items mapped to the cognitive and affective dimensions of engagement [29], as outlined in Figure 7.The latest updates on the SEI instrument’s validity are available for reference at http://checkandconnect.umn.edu/research/ engagement.html [66]. In addition, more details on the SEI are provided as per Appendix (1,2).

Thus, educators could potentially deploy the SEI to quantitatively measure the engagement of their students at the beginning of every school term, use the results to inform and design their interventions, and then measure the efficacy of their interventions by viewing their impact on the engagement scores in the following term [27]. In addition, other qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups might be deployed to investigate further the individual cases associated with low cognitive and affective engagement scores. Such a cyclical and systematic way of measuring student engagement might aid educators to improve the educational outcomes in their schools.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there appears to be credible attempts to measure latent psychological constructs such as engagement in a reliable and valid manner through self-report methods. In particular, the SEI integrates the prominent theoretical influences of engagement within its survey instrument, addresses the multidimensional nature of the engagement construct, and reconciles the overlaps between its influencers, dimensions, and outcomes amicably. Also, the regular use of the SEI can assess students’ fluctuating and malleable relationship with education over time. Given its proven track record of reliability and validity across several teaching and learning contexts over time, it promises to be a valuable instrument to measure engagement in a high school context. Moreover, given that the SEI treats engagement as a mediator between its influencers and its outcomes, it aids in understanding the impact of important contexts (influencers) such as self, peers, school, and family on outcomes such as student achievement and attainment [47]. Consequently, the cyclical and systematic use of SEI to measure the malleable concept of engagement over time might facilitate and inform several interventions in high schools to promote it [22,33,48]. After all, “effective classrooms do not just happen. They are led by teachers who deeply understand their craft and the essential nature of the interaction between student, teacher, and context” [59].

References

- Akey TM (2006) School Context, Student Attitudes and Behavior, and Academic Achievement: An Exploratory Analysis. MDRC.

- Appleton J, Reschly A (2019) Research to practice: Measurement and reporting of student engagement data in applied settings. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Furlong MJ (2008) Student engagement with school: Critical conceptual and methodological issues of the construct. Psychology in the Schools 45(5): 369-386.

- Appleton JJ, Christenson SL, Kim D, Reschly AL (2006) Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the Student Engagement Instrument. Journal of School Psychology 44(5): 427-445.

- Appleton JJ, Silberglitt B (2019) Student Engagement Instrument as a tool to support the link between assessment and intervention: A comparison of implementations in two districts. Handbook of student engagement interventions pp: 325-343.

- Archambault I, Janosz M, Fallu JS, Pagani LS (2009) Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. Journal of adolescence 32(3): 651-670.

- AttendanceWorks (2014) Attendance in the early grades: Why it matters for reading. San Francisco CA: Attendance Works.

- Bailey V, Baker AM, Cave L, Fildes J, Perrens B, et al. (2016) Mission Australia's 2016 Youth Survey Report. Mission Australia.

- Betts JE, Appleton JJ, Reschly AL, Christenson SL, Huebner ES (2010) A study of the factorial invariance of the Student Engagement Instrument (SEI): Results from middle and high school students. School psychology quarterly 25(2): 84.

- Callingham M (2013) Democratic youth participation: A strength-based approach to youth investigating educational engagement. Youth Studies Australia 32(4): 48.

- Cash AH, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ (2015) Observations of student behavior in Nonclassroom settings: A multilevel examination of location, density, and school context. The Journal of Early Adolescence 35(5-6): 597-627.

- Christenson SL, Reschly AL (2012) Jingle, jangle, and conceptual haziness: Evolution and future directions of the engagement construct. Handbook of research on student engagement pp: 3-19.

- Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Appleton JJ, Berman S, Spanjers D, et al. (2008) Best practices in fostering student engagement in (Eds), Best practices in school psychology. National Association of School Psychologists, pp: 1099-1120.

- Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C (2012a) Handbook of research on student engagement (1st edn) in Springer-Verlag.

- Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C (2012b) Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Connell JP, Wellborn JG, MR Gunnar, LA Sroufe (1991) Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes in (Eds) Self-processes and development, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc pp: 43-77.

- Conner J O, Pope D C (2013) Not just robo-students: Why full engagement matters and how schools can promote it. Journal of youth and adolescence 42(9): 1426-1442.

- Douglas F, Nancy F, Quaglia RJ, Smith DLLL (2018) Engagement by Design Corwin Literacy.

- Downer JT, Rimm Kaufman SE, Pianta RC (2007) How do classroom conditions and children's risk for school problems contribute to children's behavioral engagement in learning? School psychology review 36(3): 413-432.

- Eccles JS, Lerner RM, L Steinberg (2004) Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit in (Eds.) Handbook of adolescent psychology pp: 125-153.

- Eccles JS, Midgley C (1989) Stage-environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for young adolescents. Research on motivation in education 3(1): 139-186.

- Finn JD (1989) Withdrawing from school. Review of educational research 59(2): 117-142.

- Finn JD, Voelkl KE (1993) School characteristics related to student engagement. The Journal of Negro Education 62(3): 249-268.

- Finn JD, Zimmer KS (2012) Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In Handbook of research on student engagement pp: 97-131.

- Franklin H, Harrington I (2019) A review into effective classroom management and strategies for student engagement: Teacher and student roles in today's classrooms. Journal of Education and Training Studies 7(12).

- Fredricks J, J Wright (2015) Engagement In: (Ed) The international encylopedia of social and behavioural sciences 2.

- Fredricks J, McColskey W, Meli J, Mordica J, Montrosse B, et al. (2010) Measuring Student Engagement in Upper Elementary through High School: A Description of 21 Instruments. Issues & Answers. REL 2011-No. 098. Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast.

- Fredricks J A (2014) Eight myths of student disengagement: Creating classrooms of deep learning. Corwin Press.

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH (2004) School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of educational research 74(1): 59-109.

- Fredricks JA, McColskey W (2012) The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In Handbook of research on student engagement Springer pp: 763-782.

- Fredricks JA, Reschly AL, Christenson S L (2019) Interventions for student engagement: Overview and state of the field. Handbook of student engagement interventions 1-11.

- Fredricks JA, Wang MT, Linn JS, Hofkens TL, Sung H, et al. (2016) Using qualitative methods to develop a survey measure of math and science engagement. Learning and Instruction 43: 5-15.

- Gonski D, Arcus T, Boston K, Gould V, Johnson W, et al. (2018) Through growth to achievement: Report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Goss P, Sonnemann J (2017) Engaging students: Creating classrooms that improve learning. Grattan Institute.

- Governments C o A (2009) National partnership agreement on youth attainment and transitions. Council of Australian Governments Canberra.

- Governments CA (2016) Council of Australian Governments-Report on Performance 2016. Commonwealth of Australia, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Henrie CR, Halverson LR, Graham CR (2015) Measuring student engagement in technology-mediated learning: A review. Computers & Education 90: 36-53.

- Henry KL, Knight KE, Thornberry TP (2012) School disengagement as a predictor of dropout, delinquency, and problem substance use during adolescence and early adulthood. J Youth Adolesc 41(2): 156-166.

- Hofkens TL, Ruzek E (2019) Measuring student engagement to inform effective interventions in schools. In Handbook of student engagement interventions pp. 309- 324.

- Hulleman CS, Godes O, Hendricks BL, Harackiewicz JM (2010) Enhancing interest and performance with a utility value intervention. Journal of Educational Psychology 102(4): 880.

- Kahu ER (2013) Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in higher education 38(5): 758-773.

- Keating J, Savage GC, Polesel J (2013) Letting schools off the hook? Exploring the role of Australian secondary schools in the COAG Year 12 attainment agenda. Journal of Education policy 28(2): 268-286.

- Kotler P (2000) Marketing management: The millennium edition. Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River.

- Ladd GW, Dinella LM (2009) Continuity and change in early school engagement: Predictive of children's achievement trajectories from first to eighth grade? Journal of Educational Psychology 101(1): 190-206.

- Lam S, Wong BPH, Yang H, Liu Y Lam, Shui Fong (2012) Understanding Student Engagement with a Contextual Model. In: Christenson S, Reschly AWC (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 403-419).

- Lamb S, Jackson J, Walstab A, Huo S (2015) Educational opportunity in Australia 2015: Who succeeds and who misses out.

- Leary MR (2004) Introduction to behavioral research methods (4th). Pearson Education Inc.

- Li Y, Lerner R (2011) Developmental trajectories of school engagement across adolescence: Implications for academic achievement, substance use, depression, and delinquency. Dev psychol 47(1): 233-247.

- Lovelace MD, Reschly AL, Appleton JJ (2017) Beyond school records: The value of cognitive and affective engagement in predicting dropout and on-time graduation. Professional School Counseling 21(1).

- Lovelace MD, Reschly AL, Appleton JJ, Lutz ME (2014) Concurrent and predictive validity of the student engagement instrument. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 32(6): 509-520.

- Marraccini ME, Brier ZM (2017) School connectedness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A systematic meta-analysis. Sch Psychol Q 32(1): 5-21.

- Martin AJ (2007) Examining a multidimensional model of student motivation and engagement using a construct validation approach. Br J Educ Psychol 77(2): 413-440.

- Mason BA, Gunersel AB, Ney EA (2014) Cultural and ethnic bias in teacher ratings of behavior: A criterion‐focused review. Psychology in the Schools 51(10): 1017-1030.

- McMahon B, Portelli JP (2004) Engagement for What? Beyond Popular Discourses of Student Engagement. Leadership and policy in schools 3(1): 59-76.

- Moreira PA, Dias MA (2019) Tests of factorial structure and measurement invariance for the Student Engagement Instrument: Evidence from middle and high school students. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 7(3): 174-186.

- Pearson PD (2014) Middle School indicators of College Readiness. The Elementary School Journal 115(2): 161-183.

- Reschly AL, Christenson SL (2012) Jingle, jangle, and conceptual haziness: Evolution and future directions of the engagement construct. In Handbook of research on student engagement pp. 3-19. Springer.

- Rimm Kaufman SE, Baroody AE, Larsen RA, Curby TW, Abry T (2015) To what extent do teacher–student interaction quality and student gender contribute to fifth graders' engagement in mathematics learning? Journal of Educational Psychology 107(1): 170.

- Sinclair MF, Christenson SL, Lehr CA, Anderson AR (2003) Facilitating student engagement: Lessons learned from Check & Connect longitudinal studies. The California School Psychologist 8(1): 29-41.

- Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2016) Teacher stress and teacher self-efficacy as predictors of engagement, emotional exhaustion, and motivation to leave the teaching profession. Creative Education 7(13): 1785-1799.

- Skiba RJ, Michael RS, Nardo AC, Peterson RL (2002) The color of discipline: Sources of racial and gender disproportionality in school punishment. The urban review 34(4): 317-342.

- Skinner E, Furrer C, Marchand G, Kindermann T (2008) Behavioral and emotional engagement in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic. Journal of Educational Psychology 100(4): 765-781.

- Skinner EA, Kindermann TA, Furrer CJ (2009) A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children's behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and psychological measurement 69(3): 493-525.

- Skinner EA, Pitzer JR (2012) Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In Handbook of research on student engagement pp. 21-44.

- Sullivan AM, Johnson B, Owens L, Conway R (2014) Punish them or engage them?Teachers' views of unproductive student behaviours in the classroom. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 39(6): 43-56.

- Te Riele K (2014) Putting the jigsaw together: Flexible Learning Programs in Australia Final Report. Government or Industry Research.

- Thomas J (2019) Managing Behavior or Promoting Engagement? In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education.

- Turner JC, Meyer DK (2000) Studying and understanding the instructional contexts of classrooms: Using our past to forge our future. Educational Psychologist 35(2): 69- 85.

- Virtanen T, Moreira P, Dias A, Oliveira JT, Kuorelahti M (2013) Cross-cultural validation of the Student Engagement Instrument (SEI): The cases of Portugal and Finland. Presentation at the first international congress student's engagement in school: Perspectives of psychology and education, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Wang MT, Amemiya J (2019) Changing beliefs to be engaged in school: using integrated mindset interventions to promote student engagement during school transitions. In Handbook of student engagement interventions pp: 169-182.

- Wang MT, Chow A, Hofkens T, Salmela Aro K (2015) The trajectories of student emotional engagement and school burnout with academic and psychological development: Findings from Finnish adolescents. Learning and Instruction 36: 57-65.

- Wang MT, Fredricks JA, Ye F, Hofkens TL, Linn JS (2016) The math and science engagement scales: Scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learning and Instruction 43: 16-26.

- Wang MT, Holcombe R (2010) Adolescents' perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American educational research journal 47(3): 633-662.

- Wang MT, Peck SC (2013) Adolescent educational success and mental health vary across school engagement profiles. Dev Psychol 49(7): 1266-1276.

- Wang MT, Fredricks JA (2014) The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child development 85(2): 722-737.

- Waxman HC, Tharp RG, Hilberg RS (2004) Observational research in US classrooms: New approaches for understanding cultural and linguistic diversity. Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Wood BK, Hojnoski RL, Laracy SD, Olson CL (2016) Comparison of observational methods and their relation to ratings of engagement in young children. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 35(4): 211-222.

- Yazzie Mintz E, McCormick K (2012) Finding the humanity in the data: Understanding, measuring, and strengthening student engagement. In Handbook of research on student engagement pp: 743-761.

- Yeager DS, Henderson MD, Paunesku D, Walton GM, D'Mello S, et al. (2014) Boring but important: a self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol 107(4): 559-580.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...