Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Review Article(ISSN: 2641-1768)

Implementing Change in an Organization: A General Overview Volume 1 - Issue 1

Dave Higgins and Paul Andrew Bourne*

- Statistician, Northern Caribbean University, Jamaica

Received: August 22, 2018; Published: August 29, 2018

Corresponding author: Paul Andrew Bourne, Statistician, Northern Caribbean University, Jamaica

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2018.01.000102

Abstract

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

As human beings we tend to be averse to change and resistant to anything that threatens the status quo. All organizations require constant change and innovation for improvement. Educational changes are often perceived by some of the stakeholders as being so problematic, that is, it is not the nature of the change itself but the nature of the knowledge, skills and attitudes. This review selectively examines some of the theoretical and empirical organizational change literature, and the implementation of change in organization. Two of the cornerstone models or theories for understanding and implementing organizational change are presented in this review. The one developed by Kurt Lewin in the 1940’s and the other developed by Lippitt, Watson, and Westley in 1958. These two models still hold true today. Research dealing with the behavioral reactions to change is also reviewed. The importance of trust is explored because whenever change is announced in any organization, the level of trust soars high on the radar of communication and relationships Bourne et al. [1]; Bourne et al. [2]; Bourne [3]; Fukuyama [4]. In other words, trust becomes a critical factor in influencing how the employees think, feel, and act with respect to the current change. In closing, the general observation is advanced that change may occur, whether we like it or not, and leadership should first consider how change affects employees before implementing change initiative. Also, the evaluation of the improvement (program or intervention) to uncover “what works” is a crucial part of implementing change in an organization.

Keywords: Change; Change Implementation; Change Theories; Leadership; Organization

Introduction

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

A famous saying by Francois de la Rochefoucauld states that the only thing constant in life is change Fuller [5], which came from the doctrine of Heraclitus that things are continuously changing in life Kahn [6]; Hussey, [7]. Fortunately, or unfortunately, that is true. It is unfortunate because people can take years to make a significant difference, but time can quickly deteriorate all those efforts. Change can be a decline of something good. At a glance, the question must be asked are teachers ready to change the world in our classrooms especially at the beginning of a new school year? However, that fire of passion dies out as time goes along. As a result, people to accept mediocrity and settle for whatever comes to only to earn a pay cheque. People whom have lost their drive to work beyond a pay cheque experience a difficulty finding innovative ways to grow as a professional and individual, and this mental-stagnant destroys all forms of human development. Generally, people are positive, and this does not mean that are willing to accept change. In fact, Fukuyama [4] as well as other scholars Bourne et al. [1]; Bourne et al. [3] have forwarded that people are resistant to change. Fukuyama opined that uncertainty is the hallmark that bars people’s willingness to embrace change. Undoubtedly, highly effective people, leaders, are change agents in many respects from

a. How they see and interpret things-their paradigms.

b. There characters-they are of high integrity, humility, modesty, simplicity, justice oriented, patience, courageous, fidelity, temperate.

c. High image of self (personality).

d. How they change their social space by being steadfast to their inner-vision.

e. How they see the problem in their social settings.

These individuals, effective leaders, recognize that they cannot solve the current problems in the social system with the same thinking, paradigm, and that a change in paradigm holds the key to addressing social ills. This is aptly argued by Stephen Covey [8] using a statement made by Albert Einstein, the renown Theoretical Physicist, “The significant problems we face cannot be solved at the same level of thinking we were at when we created them” Covey [9]. This means that there must be a change in paradigm, thinking, before we can address social ills (or social problems) as the action that created it cannot be used to solve it. Such a reality, therefore, accounts of why all the effective leaders including Jesus of Nazareth, Marcus Garvey, Nelson Manley et al. [10] had the position that a new paradigm must be used to solve the social challenges that they see at the time.

Fortunately, the opportunity to improve is just as probably as the opportunity to fail. The reality is, effective people (or leaders) are not afraid to fail and this accounts for their willingness to chart new pathways and navigate a path of risk. Hence, it is indeed possible to improve or change one’s thinking and embrace change and uncertainty. The school environment is no different and teachers, administrators and other educators must be willing to embrace change in a changing milieu. The teachers will be able to perform better if they embrace change. By embrace change, teachers will be able to address students’ needs, understand new pathways, and facilitate a teaching-learning process that is conducive to learning and development. Change by the teacher is good as the basis for more opportunities for students to learn new approaches and discover new ideas. Generally, improvement of old approaches is one of the key elements to change and other scholars argued that this is filling up the potholes of the organization Colliton [11]. This paper is framed within a social constructivist epistemology. It means that the researchers are guided social constructionism. Crotty [12] opines that “…Constructionism claims is that meanings are constructed by humans being as they engage with the work they are interpreting” (p. 43), offering a premise for how this paper was done. With the purpose of the paper being an evaluation of change and implementing change, the researchers believe that such issues impacts on people and must be examined from a socially constructivist perspective because it lends itself to values, norms, and attitudes of people. Hence, the researchers employed a phenomenological research methodology, which explains the choiced method of document analysis and thematic identifications [12,13]. The authors therefore do not take the stance there is an absolute truth to the issue as there are various ways to chart a path for change; which is underlining reason for a social constructivist epistemology and how they collected the materials for interpreting the issues. As such, this will allow for greater insights into the phenomena by way of analyzing different views on the issues.

Theoretical Framework

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

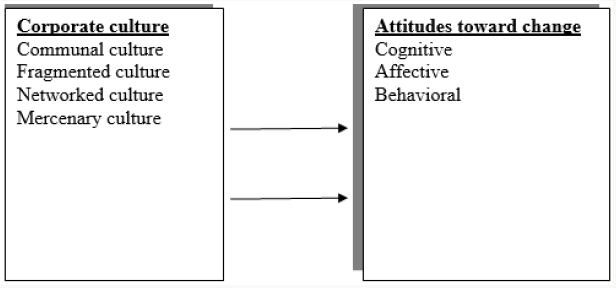

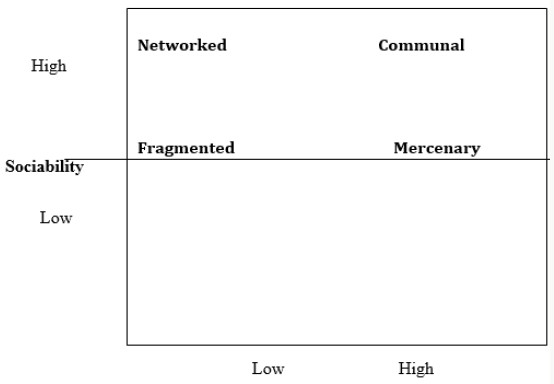

A group of academic scholars applied the principles embedded in econometrics to establish a theoretical framework that accounts for organizational culture and how this influences organizational change Durham et al. [14], Goffe and Jones [15], Rashid [16]. [15] opined that organizational culture can be categorized into four components which are then classified under

- sociability

- solidarity

They defined sociability as the extent of the friendliness between peoples in the organization, and solidarity as the ability of the individuals to pursue shared objectives in an efficient and effective manner. Based on Goffe and Jones [15] theorizing, the four components of organizational culture are

- Communal culture

- Fragmented culture

- Networked culture

- Mercenary culture

And Dunham et al. [14] introduced three factors that can influence change. These are

- Cognitive

- Affective

- Behavioral attitudes to change.

Rashid et al. [16], then, questioned organizational change within the context of [14] theorizing. They asked the question “Should organizational changes start by adopting the cognitive or affective mode and then followed by the behavioral mode?” The theoretical model (framework) that was developed, therefore, was expressed in a diagram, which emerged from an objectivist epistemology by way of objective measurement, probability sample of population, and the use of statistical tool to analyze collected data. Such a theoretical model was also used by Rashid and colleagues to investigate ‘The influence of organizational culture on attitudes toward organizational change’ Rashid et al. [16], which is presented below Figure 1: Embodied in the aforementioned ‘Theoretical model’ are four independent factors that influence attitudes toward organizational change, and the attitudes are classified into three sub-headings

- Cognitive

- Affective

- Behavioral

Such a theoretical model used the tools in econometric analysis (or statistical modeling used in economics to build model to explain issues) to arrive at the factors, which can be tested by other researchers. Rashid et al. [16] wrote that “From the above literature and the model of the study, it is hypothesized that there is an association between organizational culture and attitudes toward organizational change” Rashid et al. [16], suggesting that ‘Theoretical Model’ is testable using data.

Using an ‘Econometric Model’, [16] found a significant statistical association between organizational culture and attitudes towards organizational change (χ2 (6) = 82.764, P < 0.0001). On disaggregating ‘organizational culture’ and ‘attitudes toward organizational change’, [16] found that there is a relationship between types of culture and affective attitude (χ2 (6) = 68.497, P < 0.0001); types of culture and behavioural attitude (χ2 (6) = 48.151, P < 0.0001); and types of culture and cognitive attitude (χ2 (6) = 82.764, P < 0.0001). A P value of less than 0.05 (or 5%) indicates statistical association between the selected variables in a study. As such, it can be concluded that organizational culture plays a critical role in organizational changes, be it acceptance or rejection which is in keeping with other studies Ahmed [17], Lorenzo [18], Silvester and Anderson [19], Pool [20], Yousef [21]. And Wise [22] postulated that economic and budgetary restraints are among the endogenous determinants of organizational change, indicating that advanced statistical methodology is employed in ascertain ingredients of institutional changes.

Rashid et al [16] work found that people organizational type (i.e., mercenary) is more likely to have a strongly positive attitude to organizational changes compared to the other organizational typologies such as fragmented, networked and communal culture. They reported that among those in fragmented culture, 10% had a strongly positive attitude toward organizational change compared to 18.4% of those in networked culture, 78.5% in mercenary culture and in the communal culture, and 57.5% had a strongly positive attitude towards organizational changes. This provides some explanation for a perspective forwarded by Rashid et al that “One major issue confronting organization is to determine which type of organizational culture favors organizational change” [16], suggesting that some organizational cultures are retardation to positive organizational changes (or reform). Such a perspective is in keeping with the Lucas and Kline’s argument that “Organizational change that alters the existing values within a culture and differentially affects groups within the organization can expect resistance” Lucas and Kline [23]. The present study examines various theoretical models including the one by [16] and by Quinn et al. [24] to examine the issue of attitude to towards change and juxtaposed this on teacher education. The rationale for such a position is to explain human challenges to change and change implementation in organizations including in the teaching profession.

Embodied in the aforementioned ‘Theoretical model’ are four independent factors that influence attitudes toward organizational change, and the attitudes are classified into three sub-headings 1) cognitive, 2) affective, and 3) behavioural. Such a theoretical model used the tools in econometric analysis to arrival at the factors, which can be tested by other researchers. Rashid et al. wrote that “From the above literature and the model of the study, it is hypothesized that there is an association between organizational culture and attitudes toward organizational change” [16], suggesting that ‘Theoretical Model’ is testable using data. Using the aforementioned ‘Theoretical Model’ found a significant statistical association between organizational culture and attitudes towards organizational change (χ2 (6) = 82.764, P < 0.0001). Disaggregating the ‘organizational culture’ and ‘attitudes toward organizational change’, [16] found that there is a relationship between types of culture and affective attitude (χ2 (6) = 68.497, P < 0.0001); types of culture and behavioral attitude (χ2 (6) = 48.151, P < 0.0001); and types of culture and cognitive attitude (χ2 (6) = 82.764, P < 0.0001). This indicates that the organizational culture plays a critical role in organizational changes, be it ac ceptance or rejection which is in keeping with other studies Ahmed [17], Lorenzo [18], Silvester and Anderson [19], Pool [20], Yousef [21]). And Wise [22] postulated that economic and budgetary restraints are among the endogenous determinants of organizational change, indicating that advanced statistical methodology is employed in ascertain ingredients of institutional changes.

Rashid et al. [16] work found that organizational type (mercenary) is more likely to have a strongly positive attitude to organizational changes compared to the other organizational typologies (fragmented, networked and communal culture). They reported that among those in fragmented culture, 10% had a strongly positive attitude toward organizational change compared to 18.4% of those in networked culture, 78.5% in mercenary culture and in the communal culture, and 57.5% had a strongly positive attitude towards organizational changes. This provides some explanation for a perspective forwarded by Rashid et al that “One major issue confronting organization is to determine which type of organizational culture favors organizational change” [16], suggesting that some organizational cultures are retardation to positive organizational changes (or reform). Such a perspective is in keeping with the Lucas and Kline’s argument that “Organizational change that alters the existing values within a culture and differentially affects groups within the organization can expect resistance” Lucas and Kline [22]. The present study will use a similar theoretical framework as Rashid et al. [16], with some modification by Quinn et al. [24] model on culture and [14] On attitude toward change to carry out this research, and hypothesizes that there is a statistical association between particular occupational culture at the divisional level hinders (or fosters) organization reform in the Jamaica Constabulary Force, primarily at the Protective Services Division, and how a particular divisional head is critical to the attitudes toward organizational change.

Organizational culture and change

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

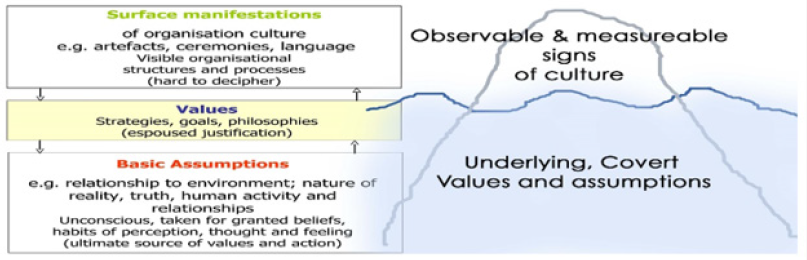

An organization’s culture is the pattern of assumptions, values and norms that are shared by an organization’s members. A growing body of research has shown that culture can affect strategy formulation and implementation as well as a firm’s ability to achieve high levels of excellence Cummings and Worley [25] Organizational culture ‘Is a pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems Schein [26].Organization culture ‘‘both a dynamic phenomenon that surrounds us at all times, being constantly enacted and created by our interactions with others and shaped by leadership behaviour, and a set of structures, routines, rules, and norms that guide and constrain behaviour.’ Schein [27] long before people become engaged in organizations, they are culturized into a set of values, beliefs, customs, traditions and assumptions of the first group, the family. The family’s biases, therefore, fashions the interpretation of how things are seen, interpreted, conceptualized and aid in a cosmology. During the early years of life of a child, knowledge is predominantly the dictates of the immediate family, nursery, and all other groups’ experiences in which the individual is self for care. Following the socialization of the child in the formative years, he/ she becomes like a sponge absorbing the lifestyle, customs, beliefs, biases and practices of the various groups (including extended family, nursery). Then, when he/she is placed in the formal education system (elementary school), the child is influenced by the groups’ behavior and group dynamics influences group learning.

The child then begins to learn the groups’ behavior while attending school and/or church, which influence learning. He/she is learning the culture of the school and the church, which emphasizes that there is a relationship between organizational culture and organizational learning which dates to childhood. Hence, so when researchers opined that there is a statistical association between organization culture and organization learning Cook and Yanow [28], Popper and Lipshitz [29], Schein [30], Lucas and Kline [23] this supports evolution of learning by way of socialization for the child. And the child is not only learning the overt behaviour, he/she is being influences by the covert underpins of the group, the group dynamics, which are equally apart of the learning process Crossan et al [31], Wastell [32], Lucas and Kline [23]. On becoming an adult and entering a job milieu, this is another group in which the individual now must learn the values, customs, beliefs, interpersonal dynamics and covert messages. The individual comes to an organization with a set of values, experiences, beliefs and customs which are not necessarily in synergy with those of the institution. People therefore must adapt to the organization to learn its codes and understanding the culture will reveal how the messages are learnt [26,30]. Embodied in the issue is re-socialization of the individual into the new organizational codes, group dynamics and practices which are alien to the new entrant. This implies that learning, re-learning, re-socialization and adaptation must be within the organization’s demand and the individual’s willingness to work in the institution.

All formal organizations, commencing with educational systems have

- Goals

- Strategies

- Structures

- Systems and procedures

- Products and services

- Financial resources

- Management

Senior and Fleming [33], suggesting that institution’s culture must be learning to order to function therein. An organization comprised of people who are combined with different sociodemographic background, values, beliefs, orientation, expectations and goals, and so there is informal aspect to the organization. Senior and Fleming [33] classified 6 areas within the informal organization:

- values, attitudes and beliefs

- leadership style and behavior

- organizational culture and norms of behavior

- power, politics and conflicts

- informal groupings

They went on to postulate that the concepts of culture, politics and power have come to embrace much of what is included in the hidden part of the organization. What is more, they play an important role in helping or hindering the process of change Senior and Fleming [33]. An organization is, therefore, equally complex as a single individual and even moreso because of the collection of varying peoples in a set space. The organizational culture has been examined by scholars and Brown [34] listed some characteristics of this. These were

- Artefacts

- Language in the form of jokes, metaphors, stories, myths and legends

- Behavior patterns in the form of rites, rituals, ceremonies and celebrations

- Norms of behavior

- Heroes

- Symbols and symbolic action

- Beliefs, values and attitudes

- Ethical codes

- Basic assumptions

- History

Another scholar’s listing of characteristics of organizational culture was somewhat different, Robbins [35] identified 7 components. The components were

- innovation (the level of creativity, innovation and risk availability is given to the employees).

- attention to details (the degree precision, analysis and attention to details that the employee is allowed).

- outcome orientation (managements emphasis on outcome).

- people orientation (people involvement in management’s decision-making process).

- team orientation (the arrangement of activities around the team or group).

- aggression (the level of aggressive and competitiveness of people).

- stability (“The degree to which organizational activities emphasize maintaining the status quo in contrast to growth” Robbins [35].

A Likert scale was established by Robbins to evaluate the organization culture using the seven mentioned characteristics of an institution. Emerging from the literature is the objective and subjective elements to organizational culture, and how scholars have sought to research the phenomenon. Robbins’ theorizing marks an illustration of an objective view of organizational culture, by listing and modeling it. Robbins’ list and model quantified the phenomenon, isolate explanatory variables and saw culture as an outcome variable that is influenced by characteristics. Culture viewed in this manner is objective or functional Alvesson [36] or could be conceptualized as a set of behavioral and/or cognitive characteristics Brown [34]. Clearly, with the context of the literature, the organization has a culture Brooks and Bate [37] similarly to the individual (Haralambus and Holborn, 2002), which extends to political organization. Munroe [38] opined that there is a political culture which denotes “attitudes, feelings, ideas, and values that people have about politics, government, and their own role, and more generally about authority in all its various forms” (p. 7), suggesting that culture is enveloped in humans and their social settings.

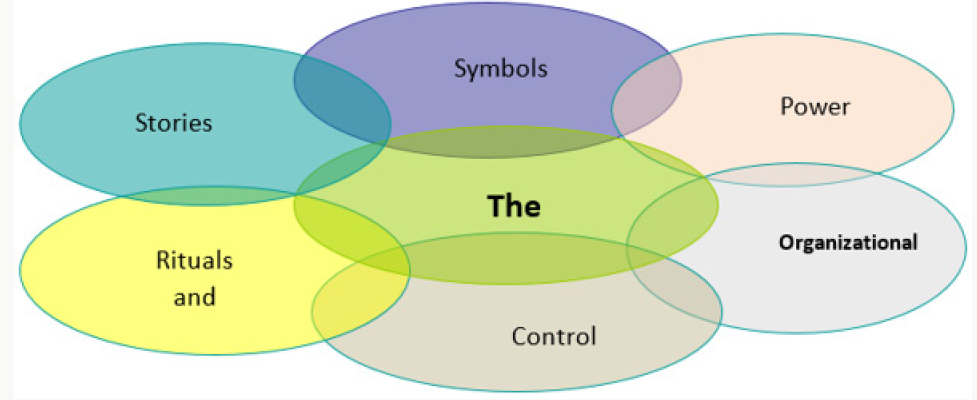

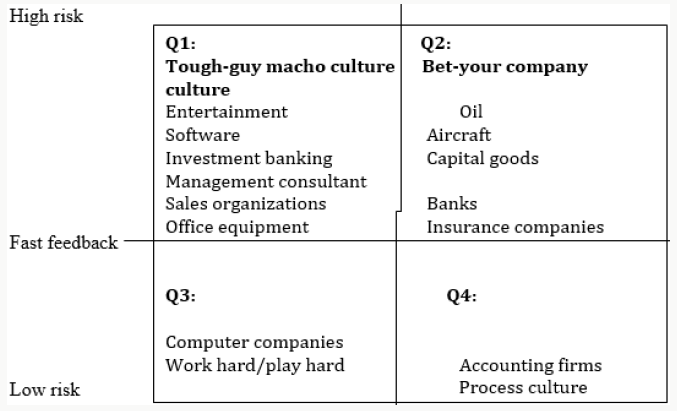

Senior and Fleming [33] argued that culture can be changed and “that changing cultures is not that difficult given the correct way of going about it” (p. 145), indicating that there is a likelihood of resistance to organizational changes as well as the culture. There is no denial that peoples’ assumptions, values and beliefs constitute the organization, which means that the organization is a web of cultural fusions. Johnson et al. [39] introduced what was called an organizational paradigm which comprises the beliefs and assumptions of the entity (Figure 3). Johnson et al.’s work highlights characteristics which are interfacing with the day-to-day operations of the organization, and how organizational change can be done if the various elements can be effectively modified. This denotes that the organizational form is a description of different structural forms and expressions, which constitutes the single institution. The organization is more than a collection of internal members to the wider society in which are operates. Deal and Kennedy [40] encapsulates the external organization (or market) in which an institution functions into four generic cultures - 1) tough-guy macho culture depicts by Quadrant 1 (Q1), 2) workhard/ play-hard culture in Quadrant 3 (Q3), 3) bet-your-company in Quadrant 2 (Q2) culture, and 4) process culture in Quadrant 4 (Q4) (Figure 4). Deal and Kennedy’s model of corporate culture unfolds another aspect to organizational culture, structure and strategy, the external environment. They identified the police department (or force) as being a part of ‘The tough-guy, macho culture’ and offered the important feature of within these cultures, burnout. Senior and Fleming [33] remarked that “Internal competition and conflict are normal, and this means tantrums are tolerated and everyone tries to score points off each other” (p. 155), suggesting that the external milieu in which the organization functions account for influencing the attitudes, values, feelings, and ideas of the people therein. It should come as no surprises that seeking to reform some cultures could be met with intense resistance, and that the people could thwart organizational changes. Reiss [41] wrote that “As we approach the twenty-first century and ponder changes of the century almost past, it would be easy to conclude that the basic structural organization of policing today resembles rather closely that in place of the beginning of this century” (p. 55). This suggests that organizational changes to alter the existing culture will be met with resistance as people do not know the outcome of these activities, the fear bolsters apprehension and mistrust could hinder the change. Lucas and Kline [23] found that trust was the most dominant issue which emerged as influencing ‘group learning to change’ (p. 280).

Because change is a futuristic outcome that is delayed about future state, one can understand the threat posed by organizations trying to change its culture. Equally important in the discourse of internal organizational change is the external environment and the risk or opportunities that are likely outside of the institution Gilgeous [42]. Some of those realities account for the difficulties in real changes in an organization alters the change process and final changes will be based on leadership style, attitude and behavior of employees, trust and cultures Rashid et al. [16]. The organization is continuously having to refashion itself to maintain and attain relevance, market share, customers’ interest and internal goals (including profitability and service delivery). The human element within the entity may be resistant to change because of the fear of the future or other issues. Dunham et al. [14] discovered that there are four aspects to the issue of change which are types of attitude to change. They identified

- affective,

- cognitive and

- behavioral.

They outlined that the affective component comprises of the attitude the individual has on an object (including like and dislike). The cognitive component being the information that is available to the person that he/she accepts is true which is used to evaluate things. And the behavioural component is the expression of the individual regarding attitude. Although the organization culture could be an inhibitor or stimulant to changes, it is also critical to the innovation and sustenance of the entity Poole [20]. This can happen within the context of the individual’s and the organization’s goals working in tandem, which could see a strong social bond. Unlike other scholars, Goffe and Jones [15] categorized culture into sociability and solidarity. They conceptualized sociability as friendly relationship between people in an organization (including ideas, attitudes, interests and shared values) and solidarity as ‘single-minded dedication’ towards the organization’s mission (or goal) Rashid, et al. [16], Ali Al-Zu’bi [43]. The two main categories were further sub-divided into four coordinates. The four main cultures in the quadrants were communal, fragmented, networked and mercenary (Figure 5). Unlike Goffe and Jones, Schein’s work on culture provides yet another view to the issue of organizational culture, which examined it from three perspective (or levels) Schein [26,27,30] (Figure 6). Schein’s model highlights the components of organizational culture, the interconnectivity among the levels, the overt and covert aspects to culture, how the organizational culture interfaces with the individual and vice versa, and how internal and external agents can retard organizational change because of the role in cultural formation and sustenance. Quinn and Spreitzer [24] were among many research scholars who examined organizational culture. Their study evaluated the relationship between organizational culture and quality of life. They measured organizational culture from four tenets. These were

- Dvelopmental culture

- Group culture

- Hierarchical culture

- Rational culture

It was found that high scores for developmental, group and rational culture were directly associated with greater score for quality of life. The group culture model examines flexibility and internal focus including cohesion, morale and human resource development. Development culture evaluates flexibility and external focus, with emphasis on readiness, growth, resource acquisition and external support mechanisms. Rational culture addresses control and external focus, where the critical areas being planning, goal setting, productivity and efficiency. Hierarchical culture highlights internal focus, with emphasis on the functions of management, communication, stability and control.

Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

Improving a school system by changing its old habits is a challenge. Old habits are hard to break. It is said that habit is hard to break because of you remove the “h” from it you have a “bit” and upon removing the “b” you still have “it.” Students, teachers, parents, and possibly some administrators may not embrace change easily. People love routine and will do everything that they can to stick to it. Unfortunately, if the administration does nothing to implement change, these same people would complain the school is not progressing. So, what is the most effective way of administering change in an institution? First, we need to identify why improvement and change need to take place. We will do this by setting up the new goals for the institution. Next, we need to look at who will have a part in the implementation of change. How the changes need to be implemented will also need to be addressed. And finally, we need to see how evaluation plays an important role in the improvement of a school.

Goals for Change

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

There are many reasons for improving systems in an organization. The goals and aims will be much more detailed, depending on what the topic for change is. But there are general goals for implementing change and improvement. Change needs to be made to help students learn. This is probably one of the most important goals for change. It is the overall reason schools exist. If students are not learning, or if their learning is being hampered by something, then changes must be made to address the cause of this hindrance. Changes should be focused on efficiency with quality. It is a given that not all schools will have the resources to provide prestige. But schools do not necessarily need to have fancy buildings and state-of-the-art facilities and equipment for students to have quality education. Sure, these are tools that will help (minus to fancy looking buildings) students to learn better. But one must be wise is making use of is economically available. If there is any chance of improving the facilities of the school, however, necessary steps need to be taken for learning to be enhanced.

Changes should encompass the professional growth of faculty and staff. If improvement is not focused on making teachers, workers, and administrators, it is impossible to accomplish the first two goals for change.

Implementers of Change

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

Everyone is an implementer of change. Of course, the administrators could officially begin the change. But in one-way or another, change is the business of all the stakeholders of the school. The students, the teachers, the administrators, the community, the donors, everyone—they are all part of influencing change in a school. Involving everyone who is somehow part of an institution is one of the most crucial parts in starting change (Reeves, 2009). If everyone does his or her part, the issue that needs transformation will resolve much quicker.

It is equally important to note that a specific body must be assigned to do planning and the official implementation of the changes. Usually, representatives of each of the stakeholders would play a part in the planning and implementation of change (Reeves, 2009).

Steps to Change

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

According to Kotter (2012), there are a number of requisites in beginning school improvement: leadership, time, skills, and will. Available leaders are needed to effectively lead the rest of the people in order for improvements to be evident. Time is one of the fundamental necessities for the planning and implementation of school improvement. Skills are a necessity that leaders need to posses. If one method does not work, a different strategy needs to be tried. Leaders must also have the will to implement change. School improvement does not happen overnight. If leaders have the will to implement change, they will be able to endure the lengthy process that school improvement requires. As mentioned earlier, making changes is not an easy task. Support from peers, colleagues, and those who will be involved in the change are crucial. If there is no support from these people, the difficulty for implementing the change will be greatly amplified. The Center for Social and Emotional Education Allen et al. [44] provides a guide for starting improvement of schools. They are listed below:

a. This was mentioned above. All who are involved in one way or another should do their part and be informed about what is going on so that change can be implemented.

b. Assess/Collect Data Regarding Where You Are: What’s Working and What’s Not? In this step, goals need to be established. It is impossible to make improvements if one does not know what to improve, so the next logical step is to investigate the needs of the institution and put it on paper. These can be patterned after the three main goals which were mentioned earlier.

c. Determine What You Believe Fundamentally as an Organization and Decide What You [Would] Like to Become: When the needs are established, what is desired should be written in the context of a goal, within the guidelines of the organization’s philosophies and beliefs. This step should address the more detailed goals, specifically targeting a area that needs improvement.

d. Do Your Homework: Investigate Research-Based Philosophies and Program: In this step, it is crucial for the leaders to investigate what has worked in the past for other institutions, what is in the books, and what could work best for the needs of that institution calls for.

e. Establish a Plan of Action: This final step before implementation of the changes is obviously making a plan of action. Once the leaders have studies what could work best for the school, the next step is to work out a plan that would be implemented in an organized, sequential manner.

Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

In 1951 Kurt Lewin, a social scientist introduced the three-step change model. He views behavior as a dynamic balance of forces working in opposing directions. According to Lewin, driving forces expedite change because they thrust employees in the desired direction. Restraining forces, on the other hand hinder change because they tend to thrust employees in the opposite direction. An analysis of Lewin’s three-step model can help shift the balance in the direction of the change that is being planned. The first step in the process of changing human behavior is to unfreeze the status quo or the existing condition according to Lewin. The status quo or the existing condition is the state in which opposing forces or influences are balanced. In other words, the status quo is the equilibrium state and unfreezing it becomes necessary so that individual resistance and group conformity is mollified. Lewin delineates three methods whereby unfreezing can be achieved. The first method is to increase the driving forces that direct the behavior away from the existing condition or status quo. The second method is to decrease the restraining forces that have a negative impact on the movement from the existing equilibrium. The third method is to discover a combination of the two methods listed above. There are many activities that can assist in the unfreezing step. Some of these activities include: motivate individuals by preparing them for the change, build trust and appreciation for the need to change, and actively participate in identifying problems and finding solutions to the problems identified Robbins [35]. The second step in Lewin’s change process is moving. The moving stage is accomplished when individuals substitute replaces old attitudes, values, and behaviors with new ones. Organizations can accomplish moving by initiating many activities such as providing training to help employees develop the new skills they need, explaining to the employees the rationale for the change and the overarching vision for the change Nelson & Quick [10].

Refreezing is the final step in Lewin’s three-step model. In this step, the new attitudes, values, and behaviors become the new status quo. This step must take place after the change has been implemented so that the new status quo can be sustained. This step requires principals to ensure that the school culture and the formal reward systems encourage the new behaviors and avoid rewarding the old ways of operation. The primary purpose of refreezing is to stabilize the new equilibrium or new status quo that emerges from the change by balancing both the driving and restraining forces [10]. Kurt Lewin’s change model, which has stood the test of time, illustrates the effects of forces that either promote or inhibit change. In other words, the model contends that an individual’s behavior is the product of two opposing forces driving forces and restraining forces. One force (restraining) pushes the individual to preserve the status quo while the other force (driving) pushes the individual to change. When the two opposing forces are approximately equal, current behavior is maintained. For behavioral changes to occur, the forces (restraining) maintaining the status quo must be overcome. According to Lewin, this can be accomplished by increasing the forces for change, by weakening the forces for the status quo, or by a combination of these two actions [10].

Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

Lippitt, Watson, and Westley (1958) Phases of Change Theory is regarded to be an expanded extension of Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory. While Lewin’s model described the process of change through three steps, Lippitt’s proposed a seven-step process that focuses on the role of the change agent throughout the advancement of the change. Simply put, this theory calls for bringing in an external change agent or consultant to put a plan in place to effect change. Lippitt and his colleagues state: The decision to make a change may be made by the system itself, after experiencing pain (malfunctioning) or discovering the possibility of improvement, or by an outside change agent who observes the need for change in a particular system and takes the initiative in establishing a helping relationship with that system (Lipitt, Watson, & Westley, 1958, p. 10).

The seven steps put forward by Lippitt and his colleagues are:

- Diagnose the problem

- Assess the motivation and capacity for change

- Assess the resources and motivation of the change agent. This includes the change agent’s commitment to change, power and stamina.

- Choose progressive change objects. In this step, action plans are developed and strategies are established.

- The role of the change agents should be selected and clearly understood by all parties so that expectations are clear.

- Maintain the change. Communication, feedback and group coordination are essential elements in this step of the change process.

- Gradually terminate from the helping relationship. The change agent should gradually withdraw from their role over time. This will occur when the change becomes part of the organizational culture (Lippitt, Watson, & Westley pp. 58-59).

Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

In scholarly studies, trust is discussed from the perspective of cognitive, affective and behavioural domains Lewicki et al [45], McAllister [46]. Stephen Covey [9] the author of The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People said that trust is the glue of life. This means that trust is the social bond that allows for all form of cooperative human existence. It’s the most essential ingredient in effective communication. It’s the foundational principle that holds all relationships. Whenever change is announced in an organization, the level of trust soars high on the radar of communication and relationships. It becomes a critical factor in how the employees think, feel, and act with respect to the proposed change. In other words, changes in organizations make trust issues salient and organizational members attend to and process trust relevant information resulting in a reassessment of their trust in management. According to Morton Deutsch [47] trust involves the juxtaposition of people’s loftiest hopes and aspirations with their deepest worries and fears. In their study about trust and its impact on employees, Piderit [48] as well as Smollan [49] explained that organizational change awakens emotional reactions with respect to both processes and outcomes and can be a major contributor to the employees’ commitment or resistance to change. The Employee perceptions of the roles of leaders are often crucial and their trustworthiness is an important element in employees’ affective responses to change Szabla [50]. Although the list for implementing change surprisingly ends here. It is obvious that evaluation, which is the final step, needs special mentioning.

Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

Evaluation is one of the most crucial parts of implementing changes in a school. The reason for this is because evaluation will allow you to know whether the plan for improvement was successful or not successful. Yap et al. [51] could not have stated it better. “Evaluation is a powerful tool that can reveal what is actually occurring in schools. It can sift through the maze of school reform efforts to uncover what is truly working to change the learning environment. It can reveal the root causes of schools’ struggles so that the real problem not just the symptoms can be tackled. It can also bring to light factors that contribute to positive results so that schools can continue to improve teaching and learning.” Once a program or intervention is implemented, you should begin to plan for an evaluation [52-55]. It is very important that mapping of the program or intervention is not only clear but comprehensive as well. In a more simplistic way evaluation is necessary to ascertain the knowledge base for “What Works” in the school improvement program or intervention. The findings obtained will inform different audiences (e.g. teachers, parents, administrators, etc.,). In other words, communication of the evaluation findings will depend on the purpose of the report and the intended audiences.

Conclusion

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

It cannot be stated enough that change is hard work. Regardless of this fact, change is something that is a necessity, not a mere phenomenon. Change may occur, whether we like it or not. However, it is in our power to direct change. In other words, change can work for or against you. We are given the privilege each day to make a difference because of this word: change. As professionals, it is our duty to make to make a positive difference where we work, how we work, and be channels of change.

References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Framework

- Literature Review

- Organizational culture and change

- Implementing and Evaluating Change

- Goals for Change

- Implementers of Change

- Steps to Change

- Lewin’s Three-Step Change Theory

- Lippitt’s Phases of Change Theory

- Importance of Trust in Change Management

- Evaluating the Improvement (Program/Intervention)

- Conclusion

- References

- Bourne PA, Beckford OW, Duncan NC (2010) Generalized Trust in an English-Speaking Caribbean Nation. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 2(1): 24-36.

- Bourne PA, Francis CG, Kerr Campbell (2010) Patient care: Is interpersonal trust missing? North Am J Med Sci 2010 2(3): 126-133.

- Bourne PA (2010) Crime, Tourism and Trust in a Developing Country. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 2(2): 69-83.

- Fukuyama F (1995) Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of prosperity. New York: Free Press p. 27.

- Fuller F (2014) The only thing constant in life is change. Emmaus Public Library.

- Kahn CH (1979) The Art and Thought of Heraclitus, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hussey E (1982) Epistemology and Meaning in Heraclitus. In Language and Logos M Schofield and M Nussbaum (eds.) P. 33-59.

- Covey S (2004a) Seven Habit of Highly Effective People. New York: Free Press.

- Covey SR (1989) The 7 habits of highly effective people. Washington.

- Nelson DL, Quick JC (2008) Understanding organizational behavior. Mason, OH. Thomson, South-Western.

- Colition JK (2005) Professional Learning Communities and the NCA School Improvement Process.

- Crotty M (2005) The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research process. London.

- Schwandt TA (1994) Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry Handbook of Qualitative Research. eds. NK: Dennis and YS Lincoln, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

- Dunham RB, Grube JA, Gardner DG, Cummings LL, Piece JL (1989) The development of an attitude toward change instrument. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Washington, DC.

- Goffe R, Jones G (1998) The character of a Corporation: How your company’s culture can make or break your business. Harper Business: London.

- Rashid Md ZA, Sambasivan , Rahman AA (2003) The influence of organizational culture on attitudes toward organizational change. The Leadership and Organizational Development Journal 25(2): 161-179.

- Ahmed PK (1998) Culture and climate for innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 1(1): 30-43.

- Lorenzo AL (1998) A framework for fundamental change: Context, criteria, and culture. Community College, Journal of Research and Practice 22(4): 335-48.

- Silvester J, Anderson NR (1999) Organizational culture change. Journal of Occupational and Organization Psychology 72(1): 1-24.

- Pool SW (2000) Organizational culture and its relationship between job tension in measuring outcomes among business executives. Journal of Management Development 19(1): 32-49.

- Yousef D (2000) Organizational commitment and job satisfaction as predictor of attitudes toward organizational change in a non-western setting. Personnel Review 29(5): 567-592.

- Wise Lois R (2002) Public management reform: Competing drivers of change. Public Administration Review 62(5): 555-567.

- Lucas C, Kline T (2008) Understanding the influence of organizational culture and group dynamics on organizational change and learning. The Learning Organization 15(3):277-287.

- Quinn RE, Spreitzer GM (1991) The Psychometrics of the Competing Values Culture Instrument and an Analysis of the Impact of Organizational Culture on Quality of Life,” in: Research in Organizational Change and Development, RW Woodman and WA Pasmore (eds.) JAI Press Inc pp 5: 115-142.

- Cummings TG, Worley CG (2005) Organization development and change. 8th edn. Ohio: Thompson South-Western.

- Schein EH (1992) Organizational psychology. New Jersey: Jossey Bass.

- Schein E (2004) Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Cook SDN, Yanow D (1993) Culture and organizational learning’. In: Cohen D, Sproull, LS, eds. Organizational learning. California 2(4): 430- 459.

- Popper M, Lipshitz R (1998) Organizational learning mechanisms: A cultural and structural approach to organizational learning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 34(2): 161-179.

- Schein EH (1993) On dialogue, culture, and organizational learning. Organizational Dynamics 22(2): 40-51.

- Crossan MM, Lane HW, White RE (1999) An organizational learning framework: from intuition to institution. Academy of Management Review 24(3): 522-537.

- Wastell DG (1999) Learning dysfunctions in information systems development: Overcoming the social defences with transitional objects. MIS Quarterly 23(4): 581-600.

- Senior B, Fleming J (2006) Organizational change, 3rd ed. London: Prentice Hall.

- Brown A (1995) Organizational culture. London: Pitman.

- Robbins SP (2003) Organizational behavior. Upper Saddle: NJ Pearson Education Inc.

- Alverson M (1993) Cultural perspectives on organizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brooks I, Bates SP (1994) The problems of effecting change within the British Civil Service: A cultural perspective. British Journal of Management 5(3): 177-90.

- Munroe T (2002) An introduction to politics: Lectures for first-year students 3rd ed.” Kingston: Canoe Press.

- Johnson G, Scholes K, Whittington R (2005) Exploring corporate strategy, texts and cases, 7th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Deal TE, Kennedy AA (1982) Corporate cultures: The rites and rituals of corporate life. MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Reiss AJ (1992) Police organization in the Twentieth century. Crime and Justice 15: 51-97.

- Gilgeous V (1997) Operations and the management of change. London: Pitman.

- Ali Al Zubi H (2011) Investigating the Relationship between Corporate Culture and Organizational Change: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences 2(2): 111- 116.

- Allen, Jennifer, Jonathan Cohen, Lauren Hyman (2002) Implementing Change: A Guide. Center for Social and Emotional Education.

- Lewicki RJ, Tomlinson EC, Gillespie N (2006) Models of interpersonal trust development: theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. Journal of Management 32(6): 991-1022.

- McAllister DJ (1995) Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal 38(1): 24-59.

- Deutsch M (1973) The resolution of conflict. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

- Piderit SK (2000) Rethinking resistance and recognizing ambivalence: a multidimensional view of attitudes towards organizational change. Academy of Management Review 25(4): 783-794.

- Smollan RK (2011) The multi-dimensional nature of resistance to change. Journal of Management and Organization 17(6): 828-849.

- Szabla D (2007) A multidimensional view of resistance to organizational change: exploring cognitive, emotional, and intentional responses to planned change across perceived change leadership strategies. Human Resource Development Quarterly 18(4): 525-58.

- Yap, Kim, Aldersebaes, Inge, Railsback, et al. (2000) Evaluating Whole- School Reform Efforts, 2nd Eds.

- Barnes FD (2004) Inquiry and Action: Making School Improvement Part of Daily Practice.

- Covey SR (2004b) The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness. New York: Free Press.

- Robbins SP (2003) Organizational behavior, (10th edn.) Pearson Education, New Jersey, USA.

- Schein EH (1996) Can learning cultures evolve? The Systems Thinker 7: 1-5.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...