Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Effect of Obesity, Socio-Economy and Interactions on Mental Health: A Study of Adolescents in Kolkata, India Volume 6 - Issue 1

Hagar Goldberg*

- The University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver Campus, 2329 West Mall, Vancouver BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada

Received:November 08, 2021; Published:November 17, 2021

Corresponding author: Hagar Goldberg, The University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver Campus, 2329 West Mall, Vancouver BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2021.06.000227

Abstract

Empathy, the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, and experience the world as you think someone else does, is a fundamental aspect of social connection, caring and belonging [1-5]. One’s ability to empathize develops gradually during childhood and is presumably influenced by children’s social environment [6-11]. If empathy is a malleable skill rather than a fixed trait [12,13], can it be nurtured and enhanced through development? What would be the experiences and interventions that would support children’s empathy development? Although empathy has been vastly studied it remained a challenging phenomenon to unlock, let alone translate into evidence- based educational practices. Here I propose a multidisciplinary approach to empathy and present a new frame work to empirically study the development of empathy.

Introduction

Scientific literature in multiple disciplines has long distinguished

two core components of empathy -- (cognitive/affective). Affective

empathy involves sharing another person’s emotional experience

(I feel your pain), through automatic simulation and mirroring

of the other person’s physiology and emotional signals, creating

an emotional resonance [14-16]. In contrast, cognitive empathy

involves recognizing and understanding another person’s feelings

and thoughts (I see and understand your pain), through mentalizing,

perspective-taking, and theory of mind (TOM) [17-20]. But what

makes some children engage and act compassionately in difficult

social-emotional situations and others to ignore or avoid them? Are

these two components (affective and cognitive) sufficient to predict

empathic behavior? What are the dynamics and interconnections

between these components? A model of higher granularity is

necessary to unravel the developmental pathways of empathy, and

to differentiate empathy from other pro-social behaviors, which

may be linked but not interchangeable (e.g., complying with social

norms and self-interest-driven collaboration).

Though the experience of empathy is salient and undeniable

(both in the giving and receiving of it), defining, controlling and

measuring it is a very different story. The definition of empathy

(what it is and what it is not), and measuring it empirically, have

been the two major challenges in studying empathy. Unlike some

basic emotions (e.g., anger, fear, joy) which have been captured

and differentiated through various physiological measurements

(e.g., facial muscles activity, skin conductance, respiratory and

heart rate measurements), empathy is a relational, multilayered

emotion which is difficult to elicit on demand and capture its

distilled essence [21]. Most empathy studies rely on adult selfreport

measures, which shed light on subjective interpretations

of empathy-related experiences in retrospect. What builds

these experiences over time, and what leads to pro-social action

remains unclear. While behavioral neuroscience offers objective,

physiological measurements, it is constrained to artificial

laboratory settings which compromise the scope and intensity of

the experience. Social development research, on the other hand,

focuses on children in their natural environment where authentic

empathy sprout in real-time, but lacks objective, high-resolution

assessments of empathy.

Currently, different interpretations and speculations around

empathy fill the vacuum created by the empathy research

limitations. One example is the ongoing debate on the links

between affective empathy and pro-social behavior. Some suggest

that affective empathy is essential in drawing our attention to

others in need [22-25], while others argue that affective empathy

distracts from making a moral decision and acting compassionately

(especially when it comes to helping an outgroup member) [12].

As long as the empathy research is fragmented and not integrated,

each discipline is able to see and describe only part of the picture. In

order to understand empathy at its core, this vague concept should

be broken down to the most basic, measurable, building blocks

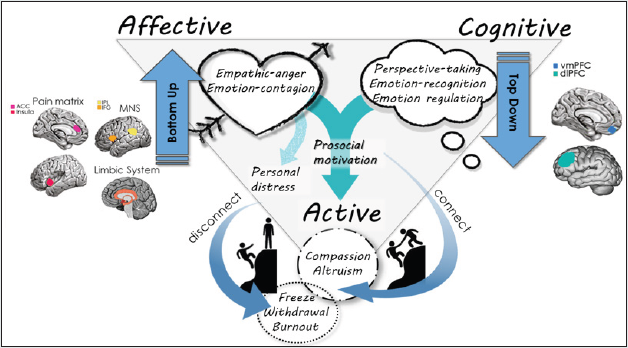

that can then be measured over time. I propose a Triadic Empathy

Model (see Figure 1) as a framework for studying empathy and its development. The Triadic Empathy Model is based on evidencebased

knowledge from neuroscience and social-emotional learning

(SEL) and invites a multidisciplinary integration between the

different facets of empathy (e.g., cognitive analysis, emotional

experience, action tendencies), through different measurements

(subjective reports, physiology and behavior).

Figure 1: The Triadic Empathy Model. Affective empathy: emotional and physiological resonance with the other person, through simulating and mirroring the other person physiology and emotional signals. This system is the earliest to develop, operates quick and spontaneously, in a bottom-up manned, activating primordial brain systems- the limbic system, pain matrix and mirror neurons. Cognitive empathy: understanding the others’ thoughts emotions and perspectives through Theory of Mind (TOM) and mentalizing. This system develops and function slower through an intentional top-down processing, and rely on the PFC (late) maturation. The author hypothesis is that a balanced and regulated social-emotional system, and a secure sense of self, leads to a healthy, restorative prosocial motivation, increase connection and active empathy and decrees social related distress.

A neurodevelopmental perspective of empathy

Empathy is a multifaceted skill that develops gradually and

hierarchically over time, through the incorporation and leverage of

several neuronal systems. Although we are not born empathetic,

empathy starts at birth. At the beginning, emotional sensing and

processing is spontaneous and automatic. Human babies are

extremely dependent; thus, connection and belonging are pivotal

for their survival. The newborn brain is evolutionarily “programed”

for seeking and benefiting from social stimuli and interaction,

a process known as ‘experience-expectant’ brain development

[26]. Human brain development is, therefore, highly dependent

on the interpersonal context and quality of early caregiver-infant

interactions which lay the neuronal foundation for empathy

development [27-30].

Notably, neurodevelopmental studies suggest that humans are

sensitive to others (social signals) even before establishing a strong

sense of self. Infants demonstrate attention bias to salient social

stimuli such as faces [5,11,22,14,16] and especially negatively

charged (angry and fearful) facial expressions [31,32]. The baby’s

perception of another person’s emotional state automatically

activates their own brain representation of this state, which primes

physiological responses accordingly. This process of emotion

contagion, the spontaneous emotional, bodily reaction to the

situation is a primal, low level facet of affective empathy [33-35]. It

Involves the limbic system, which is central in emotion processing

and memory, mirror neurons, selective to both action execution

and action observation (inferior frontal gyrus - IFG), and the pain

network, a shared matrix for experiencing and witnessing (others

in) pain (anterior insula – AI, and the dorsal anterior/anterior

medial cingulate cortex - dACC/aMCC) [36]. Neuroimaging studies

point to a developmental mechanism rooted in pain aversion and

rewarding prosocial motivations. Sensitivity to others’ emotions,

interpersonal harm aversion, and preference for prosocial

characters are early social inclinations that guide babies toward

protection, affiliation, and cooperation in their social world [7].

Over time, brain activity streams more to the prefrontal cortex

(PFC), indexing a higher level of emotional processing, and a shift

from the initial visceral response, to a more conscious, evaluative

emotional response [7]. If the primal, low-level-affective-empathy

is an autonomic emotional response to another person’s emotional

expression (e.g., emotion contagion), high-level-affective-empathy

is a feeling; an emotional experience based on bodily sensation

and the cognitive attributions one associates with the situation

of another person. The progression from low-level to high-level

affective empathy is a shift from feeling with to feeling for someone.

This shift requires concepts of self and other, social awareness, and emotional regulation, which rely on the PFC and therefore takes

time to develop. One example of high-level affective empathy is

empathic anger in reaction to another person’s unjust suffering and

victimization [30]. In their study, Vitaglione and Barnett found no

correlation between their empathic anger scale and any of the three

other anger scales that were tested. This finding suggests that,

unlike basic anger, which is a protective emotion over self, empathic

anger is a protective emotion over another person (feeling angry

for someone else), which makes it a social and moral feeling.

More recently, in a younger sample, empathic anger was found

to mediated the impact of both perspective taking and empathic

concern on how students responded when they saw others being

bullied [21]. Thus, empathic anger may be particularly relevant to

active empathic behavior.

The development of executive functions and the ventromedial

prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), enable the emerging of emotion

recognition, the awareness and ability to identify specific emotions,

a key facet of cognitive empathy. Next, throughout childhood and

adolescence, further development of the dorsolateral prefrontal

cortex (dlPFC) supports more cognitive flexibility, and with it the

ability to expand one’s perspective [7]. Perspective taking, the

deliberate and effortful process of understanding other points of

view, is another facet of cognitive empathy and one that mediates

emotion regulation skills [5,14,19]. The development of these

socio-cognitive facets of empathy enables emotion regulation and

other-oriented focus that prompts more effective and accurate prosocial

responses. Furthermore, pro-social behavior is reinforced

through a positive feedback loop. For example, altruistic behavior

has been associated with activations in the reward system (ventral

tegmental area - VTA, caudate and subgenual ACC) which, in turn,

has been found to predict subsequent helping behavior [25]. In

summary, with age and brain maturation, empathy joins bottomup

limbic activation (amygdala, posterior insula), and top-down

(vmPFC and dlPFC) activation processes, resulting in a multi-level,

regulated and integrated socio-emotional-cognitive experience

and a key precursor for pro-social behavior With this premise

that empathy is a three-dimensional construct involving cognitive,

affective, and behavioral components, I am proposing the triadic

empathy model.

From passive to active empathy; the triadic model of empathy

The Triadic Empathy Model (see Figure 1) is a framework

to conceptualize and study empathy in a multifaceted way. In

addition to the well-known Affective and Cognitive components of

empathy, Active Empathy is a third component referring to action

tendencies and behaviors propelled by the empathic experience.

Including the active part of empathy in the model enables studying

the motivational features of empathy, the direct connections that

exist among the different facets of empathy, and the dynamics of the

empathic cascade, from experience to action. From a developmental

perspective, the approach/withdrawal motivation framework

suggests that living organisms tend to approach positive and safe

stimuli and avoid negative and overwhelming stimuli, as an adaptive,

basic survival mechanism [17]. Furthermore, some emotions are

more strongly associated with approach action tendencies (e.g.,

anger) and others with withdrawal (e.g., fear and sadness) [17].

Understanding the underlying mechanisms of empathy can shed

light on children’s’ different reactions to intense social-emotional

situations, specifically, why some children demonstrate active prosocial

behavior while others stay passive or withdraw from these

situations.

The triadic model of empathy is dynamic and can be expended

to include further subdivisions of the three main components of

empathy. For example, perspective taking and emotion labeling,

both reflect cognitive analysis of emotional experiences, would

be examples of cognitive empathy. This high-resolution definition

of empathy is not semantics but a practical expansion of research

possibilities. Importantly, the subdivision of affective empathy

into low-level and high-level affective empathy enables access

to new research questions about the role of emotion regulation

and compassion fatigue in the empathic experience. For example,

among children that avoid active empathy, some do not understand

the situation, some understand but do not care, and some care but

do not act. Could the third option be due to a lack of transformation

between low level to high-level affective empathy (the transition

from feeling with to feeling for someone)? Could those individuals

withdraw and score low on active empathy, not because they do

not feel it, but because they feel it too much? This frame work

allows both hypothesis and empirical design to study them. My

hypothesis (as shown in Figure 1. by the turquoise arrows), is

that a cognitively regulated social-emotional system, and a secure

sense of self, leads to a healthy, restorative prosocial motivation,

increase connection and active empathy and decrees social related

distress. This hypothesis is yet to be tested, and the triadic model

offers an empirical design to study this hypothesis as well as others.

In addition, breaking down the big components to the most basic

building blocks opens the door to specific objective measurements.

For example, active empathy could be associated with children’s

social decision making and behavior in real situations; cognitive

empathy could be associated with children’s understanding

and analysis of social situations, and affective empathy could be

measured through physiological and hormonal changes (e.g.,

oxytocin and cortisol) during social-emotional situations.

Conclusion

A multi-level assessment scale, based on self-reports with additional behavioral and physiological measurements, under one comprehansive framework would be valuable in finding further hierarchical-developmental relations between the different components of empathy, and furthermore to explain how the development of empathic experience might be translates into action.

References

- Adams F (2001) Empathy, neural imaging and the theory versus simulation debate. Mind and Language 16(4): 368-392.

- Amso D, Haas S, Markant J (2014) An eye tracking investigation of developmental change in bottom-up attention orienting to faces in cluttered natural scenes. PloS One 9(1): e85701.

- Balconi M, Canavesio Y (2013) Emotional contagion and trait empathy in prosocial behavior in young people: The contribution of autonomic (facial feedback) and Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES) measures. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 35(1): 41-48.

- Batanova M, Loukas A (2016) Empathy and effortful control effects on early adolescents’ aggression: When do students’ perceptions of their school climate matter? Applied Developmental Science 20(2): 79-93.

- Bengtsson H, Arvidsson Å (2011) The impact of developing social perspective‐taking skills on emotionality in middle and late childhood. Social Development 20(2): 353-

- Bloom P (2017) Empathy and its discontents. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21(1): 24-31.

- Cuff BMP, Brown SJ, Taylor L, Howat DJ (2016) Empathy: A review of the concept. Emotion Review 8(2): 144-153.

- Decety J (2010) The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Developmental Neuroscience 32(4): 257-267.

- Decety J, Cowell JM (2018) Interpersonal harm aversion as a necessary foundation for morality: A developmental neuroscience perspective. Dev Psychopathol 30(1): 153-164.

- Decety J, Jackson PL (2004) The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev 3(2): 71-100.

- Decety J, Meidenbauer KL, Cowell JM (2018) The development of cognitive empathy and concern in preschool children: A behavioral neuroscience investigation. Dev Sci 21(3): 1-12.

- Decety J, Michalska KJ (2010) Neurodevelopmental changes in the circuits underlying empathy and sympathy from childhood to adulthood. Dev Sci 6: 886-899.

- Doré BP, Morris RR, Burr DA, Picard RW, Ochsner KN (2017) Helping others regulate emotion predicts increased regulation of one’s own emotions and decreased symptoms of depression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 43(5): 729-739.

- Frank MC, Vul E, Johnson SP (2009) Development of infants’ attention to faces during the first year. Cognition 110(2): 160-170.

- Gallagher S (2012) Empathy, simulation, and narrative. Science in Context 25(3): 355-381.

- Greenberg G (2017) Approach/Withdrawal Theory BT-Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior (J. Vonk & T. Shackelford, Eds.).

- Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL (1993) Emotional contagion. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2(3): 96-100.

- Hoffman ML (2001) Toward a comprehensive empathy-based theory of prosocial moral development.

- Hollan D (2012a) Emerging issues in the cross-cultural study of empathy. Emotion Review 4(1): 70-78.

- Hollan D (2012b) The definition and morality of empathy. Emotion Review 4(1): 83.

- Jordan MR, Amir D, Bloom P (2016) Are empathy and concern psychologically distinct? Emotion 16(8): 1107-1116.

- Kwon MK, Setoodehnia M, Baek J, Luck SJ, Oakes LM (2016) The development of visual search in infancy: Attention to faces versus salience. Dev Psychol 52(4): 537.

- Lei Y, Wang Y, Wang C, Wang J, Lou Y, et al. (2019) Taking familiar others’ perspectives to regulate our own emotion: An event-related potential study. Front Psychol 10: 1419.

- Levy J, Goldstein A, Feldman R (2019) The neural development of empathy is sensitive to caregiving and early trauma. Nature Communications 10(1).

- Lewis M, Sullivan MW, Kim HMS (2015) Infant approach and withdrawal in response to a goal blockage: Its antecedent causes and its effect on toddler persistence. Dev Psychol 51(11): 1553-1563.

- Newman L, Sivaratnam C, Komiti A (2015) Attachment and early brain development–neuroprotective interventions in infant–caregiver therapy. Translational Developmental Psychiatry 3(1): 28647.

- Peltola MJ, Yrttiaho S, Leppänen JM (2018) Infants’ attention bias to faces as an early marker of social development. Dev Sci 21(6): e12687.

- Pozzoli T, Gini G, Thornberg R (2017) Getting angry matters: Going beyond perspective taking and empathic concern to understand bystanders’ behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence 61: 87-95.

- Schumann K, Zaki J, Dweck CS (2014) Addressing the empathy deficit: beliefs about the malleability of empathy predict effortful responses when empathy is challenging. J Pers Soc Psychol 107(3): 475.

- Songhorian S (2015) Against a broad definition of “empathy.” Rivista Internazionale Di Filosofia E Psicologia 6(1): 56-69.

- Sonnby Borgström M, Jönsson P, Svensson O (2003) Emotional empathy as related to mimicry reactions at different levels of information processing. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 27(1): 3-23.

- Stern JA, Cassidy J (2018) Empathy from infancy to adolescence: An attachment perspective on the development of individual differences. Developmental Review 47: 1-22.

- Tousignant B, Eugène F, Jackson PL (2017) A developmental perspective on the neural bases of human empathy. Infant Behav Dev 48(Pt A):5-12.

- Vaish A, Grossmann T, Woodward A (2008) Not all emotions are created equal: the negativity bias in social-emotional development. Psychol Bull 134(3): 383-403.

- Vitaglione GD, Barnett MA (2003) Assessing a New Dimension of Empathy: Empathic Anger as a Predictor of Helping and Punishing Desires. Motivation and Emotion 27(4): 301-325.

- Zhou Q, Valiente C, Eisenberg N (2003) Empathy and its measurement.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...