Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Digital Engagement in Different Cultures: Focus on Learning Communities Volume 3 - Issue 3

Lichy Jessica*

- Department of Psychology, France

Received: December 16, 2019; Published: January 08, 2020

Corresponding author: Lichy Jessica, Department of Psychology, France

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2020.03.000163

Introduction

The enquiry investigates the different ways in which academics use digital technology to deliver undergraduate business programs, paying attention to the choice of sites and services. It explores the factors that motivate academics to integrate technology into teaching, and the barriers that hinder the widespread adoption of ICT (information and communication technologies) in the classroom. The intention is not to compare the value of tradition pedagogy with innovative pedagogy; the focus is on furthering our understanding of the factors that facilitate the adoption of ICT namely successes, challenges, necessary knowledge and skills to operate the technology, implicit changes that are necessary, overall benefits to students. Collaboration within higher education is standard practice, often driven by the need to raise awareness of research activities in the international academic community, and also from an educational ethos to impart competences as widely as possible. Modern technologies share in and benefit from this collaboration both in terms of creating innovative infrastructures and through a free exchange of knowledge and experience [1]. A certain amount of research has been published on partnerships, alliances and networks within higher education, for example the work of Tugend on the alliance between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Cambridge in Great Britain. The literature on academic collaboration extends to all parts of the world including Asia, South America and the United States [2]. However, less research has been undertaken in the smaller institutions of higher education with fewer resources. Thus there is a gap in knowledge as we do not know if the same patterns and data are valid for all types of institutions.

Advances in digital technology can extend the reach and richness of academic collaboration beyond borders. Hi-tech developments offer opportunities to rethink how ICT are provided and exploited within research, pedagogy, the internationalisation process, and the management of higher education institutions [3]. rightly observe, however, that implementing technology into any organization requires adjustments that go beyond technical aspects; there are often management, financial and cultural barriers which need to be overcome in order to prepare students of today tomorrow’s world of work. A number of commentators put forward that ICT are fundamental for the globalisation of higher education and in the internationalisation processes [4-7]. ICT are essential for international research collaboration and for the creation of learning communities worldwide. In the current competitive market, institutions strive to achieve international ranking and visibility in the academic community. Technology is crucial for establishing and maintaining competitive advantage. For the purpose of this enquiry, technology refers to “the physical instrumentation that helps us carry out our tasks” [4], in other words any application of human knowledge to solve practical problems. The integration and usage of technology in higher education is a topical field of research in an era of rapid growth in the number of online courses available and the introduction of MOOC (Massive Open Online Course). Students no longer need to attend lectures in a crowded auditorium; they can follow the course online anytime, anywhere and as many times as they need. Lectures can be pre-recorded and other course content can be posted online. Realistically, however, implementing technology into learning is not so straightforward, as this enquiry will demonstrate.

Aim

This enquiry investigates the degree to which online technology is used to deliver undergraduate business programs, in particular the sites and services that faculty choose to integrate into the coursework, and those that they chose to avoid using. The aim is not to compare methods of technology-led learning with traditional teaching - but to explore the factors which influence the adoption of technology in teaching, putting the emphasis on five areas: successes, challenges, necessary knowledge and skills to operate the technology, implicit changes that are necessary, overall benefits to students.

The enquiry thus draws on field research, focusing on two queries

a) Which approaches are used for technology-led teaching in each institution?

b) What factors influence the success of implementing

technology-led teaching?

In the short-term, the intention is to raise awareness of technology-led learning at two institutions (a Franco-Russian university partnership) and to explore the extent to which faculty have integrated technology into their teaching. A longer-term objective of this enquiry is to investigate networked technology in order to develop online resources that can be shared between the institutions, tailored to the needs of the international cohort who spend a semester at each institution. Guidelines are put forward (in Appendices 2) for introducing new technology, supporting the view that technology can be used to develop a cutting edge in management education [2] based on the notion that technology can be used to develop business acumen and thus prepare students for work, since an understanding of technology and social media is a requirement for modern day businesses [8,9]. To understand the complexity of introducing new technology in this specific context, it is important to bear in mind the role played by culture and the various issues that surround the internationalisation of higher education (the genesis of the partnership). Acknowledging the work of [10], culture exists at different levels-professional, class and regional-“but it is particularly potent at the national level because of generations of socialization in the national community” [11]. “National cultures differ primarily in the fundamental, invisible values held by a majority of their members, acquired in early childhood, whereas organizational cultures are a much more superficial phenomenon residing mainly in the visible practices of the organization, acquired by socialization of the new members who join as young adults” [12]. That is, national cultures evolve very slowly whereas organizational cultures can be consciously changed. The extent to which this notion is applicable to technology adoption in a Franco-Russian university partnership is discussed later.

From internationalisation to technology-led learning in higher education

After the fall of the Berlin Wall many international collaborative ventures were formed in which Western developed economies set out to transfer knowledge to Eastern transition economies [13]. In contrast to the business world, there has been more reciprocal interdependence and two-way knowledge transfer among academics [14]. Developments in ICT have enabled faster communication and information flows between institutions, enabling greater international collaborative work. ICT have also led to the increased use of technology-led learning in higher education and this has challenged faculty and their practice [15]. The growing number of publications on introducing and using technologyled learning reflect the importance of the topic ; illustrations of successful implementation are plentiful, underscoring the justification for technological change. The Leitch Review of Skills (2006) describes how online learning can play a key role in the drive towards increasing skills levels, based on the belief that online learning is an effective way to provide an individualised learning experience, while offering opportunities for collaborative learning through discussion forums and instant messaging technologies. It is agreed that “e-learning also provides a relatively anonymous learning environment, so there is less pressure to perform well in front of colleagues as might sometimes be the case in classroomstyle training” [16]. The work of Vygotsky (1978) emphasizes how learning is acquired through collaboration when the individual is placed at the centre of the learning experience, embracing the ethos of technology-led learning. The overarching theme in literature is that the use of technology in the classroom has a positive impact on students’ academic performance.

Digital technology has multiplied the opportunities for diversified styles of teaching and learning, interactive media enable learners to co-construct knowledge through asynchronous discussion boards, chat rooms, web conferencing, online social networks, wikis and blogs [17]. Provided that the infrastructure is in place and that there are enough resources (especially bandwidth), these tools can be used to complement (rather than replace) the more traditional methods of teaching. Combining online and offline methods can enrich the learning experience when tailored to the student learning styles. Richmond and Cumming (2005) suggest using Kolb’s theory of learning styles as a basis for designing online course instruction [18]. The work of Bandura [19] argues that people can learn new information and behaviour by observing, imitating and modeling other people either live or from video such as those used by the Khan Academy and TED-Ed Lessons Worth Sharing. The use of online course materials can increase interaction among students, and between the students and the teacher - for example through virtual group work, building an online community for a module, discussion questions, peerreviewed online activities, instructor participation and so on. Many institutions offer ‘virtual distance learning’ or e-learning which allows teachers and students to interact with each other online, either in real-time or asynchronously. Digital technology provides the potential for establishing communities of inquiry in which elements of social presence, teaching presence and cognitive presence interact to create an educational experience. Supporting this notion, the work of McCombs and [20] holds that online learning can empower students to become more independent and to take control of their learning [21]. online technology “has moved into the mainstream of higher education and is beginning to be recognized as a strategic asset”. Furthermore, the Strategic Framework for European Cooperation in Education and Training “ET 2020” confirms that politicians have recognised that education and training are essential to the development of today’s knowledge society and economy. In higher education, the emphasis needs to be on providing people with the right blend of high-level skills which will enable them to not only to be able to operate the technology, but also to be able to recognize and comprehend what it means to live in a web-based, networked society [22]. Hiltz, Turoff [23] state that the current evolution taking place in educational technology and pedagogy will be seen in the future as “revolutionary changes in the nature of higher education as a process and as an institution”. Tonks [24] reminds us that “while educational technology can enrich learning experiences and outcomes, it is not axiomatic that such enrichment will follow”.

For the moment, it is thought that “most students still prefer face-to-face contact” [25], although a growing number of studies suggest that traditional forms of teaching such as lectures do not provide an optimal learning experience for students [26-28]. Owing to growing competitive pressure, many institutions of higher education have shifted to a more “market-led culture” [29] hence the current discourse surrounding the student as a consumer, financial sustainability, government regulations and corporate responsibility [30]. While institutions have contributed to the development of societies in transition, mainly in post- communist countries, Brennan [31] point out that the expansion of higher education was launched, not “because of a belief in the intrinsic good of education [but for] more instrumental purposes to do with economic development, social cohesion, national identity and so on”. Current literature highlights the notion that higher education institutions are under increasing pressure to internationalize in order to achieve competitive advantage, and ultimately to improve their international ranking.

ICT play a fundamental role in internationalisation by providing opportunities for greater cross-border collaboration through pooling ideas and resources, given the current challenges of increased competition, higher costs, declining population and changing demographics [32] and where the bottom line is increasingly important [33,34]. ICT cross languages and cultures, providing new opportunities in international education where the student cohort is often very culturally and linguistically diverse. However, many complex factors influence the adoption of technology in teaching, and thus usage and perception vary greatly. The world is passing through a technological revolution, but many institutions lack useful, reliable information to guide decisions on implementing new ICT [35]. Some prefer to do nothing rather than embrace technological change. There is a certain reluctance to invest in new teaching and learning technology without having proof that it works. Many faculty want to carry on using face-toface instruction, rejecting innovative pedagogy on the grounds of being an impersonal delivery method or overly-automated assessment process, plus there are concerns about plagiarism and isolation of learners. The tech industry has responded well to such criticisms by providing online materials that can be customised, incorporating each learner’s progress, detailed tutor feedback and tracking ‘attendance’. Despite the reservations, online learning has grown rapidly in the last decade, especially in the English-speaking world, fuelled by a greater demand for personal development along with learning and lifestyle changes within society. But how far does this notion apply to non-English-speaking institutions, in this case Russia and France? And how does it apply in transition economies– namely Russia? Although the Internet is an established channel of communication worldwide, a vast array of factors that can broadly be described as a country’s ‘culture’ or ‘worldview’ continue to influence the way ICT are used and perceived, particularly in education where the introduction of digital technology moves the focus away from pedagogy to acquiring a prescribed set of technology skills. Evoking the popular ‘iceberg model’, many tangible and intangible factors influence technology acceptance and user behaviour, and thus how technology can be integrated into teaching.

In the cultural context of Russia and France, teachers seem to ‘own’ and deliver knowledge. Consequently, sharing knowledge via digital tools is new territory. This can partly be explained by national culture (avoiding uncertainty) but also occupational culture (knowledge is power). These imperceptible factors draw attention to the socio-cultural differences that exist in Russia and France which can hinder the implementation of digital technology in teaching methods. Furthermore, student reactions to technologyled learning can differ depending on their prior experience and on the distinct communication norms across different cultures [14]. It is clear that more research from an international perspective is needed to develop ‘best practice’ in the integration and usage of technology-led learning in higher education.

The Russian Context

The challenges facing higher education in Russia are not

dissimilar from those in other transition economies; there is a need

to challenge and change what has successfully worked before-and

this can create opposition and resistance within universities and

in society at large. Kortunov [36] states that the specific features

of Russia have always been the imbalance between an excessively

strong state and a profoundly weak society which continues to

influence the whole system of higher education in the country.

There is a lack of a clearly determined national policy on the

promotion of the Russian system of higher education. The relative

weakness of market mechanisms in the national economy at large

and in education especially is another factor [37,38].

Higher education institutions in Russia still have to interact with

state bureaucracies for funding, standards and legitimacy. They are

financially “struggling for survival” [39]. The state continues to play

a central role in licensing, accreditation and general oversight, even

for the emerging private sector in higher education. Within the

Russian educational community, this dependency is considered a

burden and many universities strive to achieve greater autonomy

from state bureaucrats. Given that “the continuity of the old

political class transformed into an economic elite” [40], the higher

education system today in Russia can be described as a blend of

both Soviet and post-Soviet traditions [39]; still very hierarchical

[41] but with a new orientation towards commercial gain [42],

though nevertheless elitist [43].

Historic events have transformed Russian universities over

time. One of the more recent changes concerns the Bologna

process-the harmonization of academic and higher education

communities across Europe - providing an opportunity for

international collaboration but also international competition,

and thus a potential threat to national identity. In the international

marketplace, the globalization of higher education was inevitable;

“Russia has to be pro-active, to define its interests, to evaluate the

attendant risks and costs, and to map out the practical policies”

[44]. To meet the challenges brought about by globalizing forces,

Russian universities need to develop new skills and knowledge at every level-personal, professional and development competencies

[45]. In the 1990s, the regime was reinforced by the transformation

of the elite from the Soviet era into a powerful agent influencing

both the pace and direction of change, with a vested interest in the

preservation of the post-socialist regime [46]. Many ‘institutional

lock-ins’ were created whereby “the state of one institution is

influenced by the state of that institution at a preceding time” [47],

for example, the conflict today between the labour market (the

need for qualified specialists is not high) and the growing trend to

study at university (most families in Russia want to send their child

to university) [48]. There is conflict between the quality of teaching

and the price paid by parents for their children’s tuition.

In the Franco-Russian partnership, what scope is there to

learn from each other in the use of technology for teaching in an

international context? The work of Batjargal [49] describes Russia

as a high relationship-oriented culture where an individual defines

oneself in relation to others and where relationship often matters

more than rules in decisions. France, on the other hand, is low

relationship-oriented where individualism prevails and where

decisions are guided more by institutional rules than relationships

[50]. Culturally different, each institution has elements of best

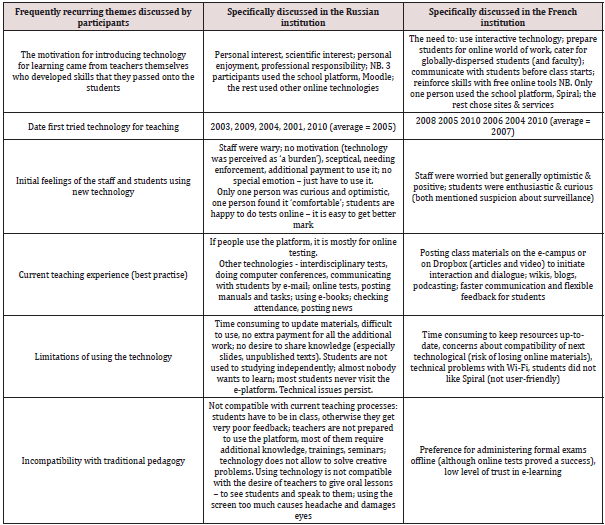

practice, knowledge and experience to share (Table 1).

The French Exception

study by [51] Recherche (Ministry of State Education, Higher Education and Research)- found that many French higher education institutions currently lack the pedagogical approach and requisite skills for using a technology-enhanced learning. The problem concerns motivation as much as management [52]. Faculty need to be trained in social constructivist teaching methods, in order to appreciate the benefits of using such an approach-in preference to the habitual teaching style in France based on an authoritative relationship where the teacher dispenses knowledge to the students [53] and using thing the traditional face-to-face teaching model [54].

The French education system remains extremely discriminatory; a handful of prestigious institutions educate the elite, to the exclusion of the lower echelons of society who desperately lack resources to compete [55]. The system is not geared up to an open learning approach based on sharing knowledge and experience. Teaching and learning is highly classroom-based [56] and one very long-standing feature of French society is intellect. Where America lays emphasis on money, Great Britain blood, France chose the concept of cleverness [57]. This is clearly illustrated in the education system where its role is seen to be to transmit knowledge and to train intellects rather than develop the full individual [56]. Changing the institutional culture seems to be relatively slow in the French cultural context; educational reforms are regularly met with unbending resistance. To prepare for change, a national debate was held in 2006 to discuss the future of higher education in France; technology-led education was not on the agenda. Seven years later, professional bodies such as INRP - Institutes national de recherche pedagogue (French institute of teaching research)-now advocate the integration of social media in the curriculum. But many argue that this move is not sufficient to stop French students enrolling at foreign institutions that have fully integrated technology-led learning. Today’s students want to live, work and study online [58].

At the time of writing, the French institution in this study has integrated two pieces of software; firstly, an e-campus open-source platform which is used primarily for posting information and course documents as it offers few collaborative tools; and secondly, Spiral, an e-learning platform developed by a local university which offers a significant range of useful collaborative tools but whose existence seems to be ignored by the majority of teaching staff. Discussions are currently underway to plan the introduction of ‘innovative pedagogy’ for post-graduate students by developing an approach based on ‘flipping the classroom’–in other words, a teaching model that delivers instruction outside the classroom, for example at home, through interactive, teacher-created videos. Moving lectures outside of the classroom allows teachers to spend more one-to-one time with each student, both face-to-face and virtually. Students have the opportunity to ask questions and work through problems with the guidance of their teachers and the support of peers, thus creating a collaborative learning environment. In the case of the French institution, the idea is to implement technology-led learning with the post-graduate students, then use feedback to develop an approach adapted for undergraduate students.

Comparing the pedagogical approaches used in the Russian and the French institutions, it is fair to say that many teachers are unaccustomed to using technology for teaching; this is equally true for teachers and students. However, both institutions have started to recognize the importance of using modern technology in teaching, not only as an academic resource but as a competitive advantage too. In order to raise awareness of technology-led learning at each institution - and ultimately to develop online resources that can be shared between them-it is constructive to audit the technology skills of the teaching staff, prior to providing technical training to bridge the skills gap. The introduction of technology-led learning will oblige faculty to relinquish some of their control in the teaching process in order to allow for student empowerment and the creation of learning communities. This aspect is likely to bring about a change in the existing culture within the institution and, all being well, a willingness to learn new skills to develop innovative methods of learning. Introducing technological change takes time to set up and deliver; it represents a considerable cost to the institution in terms of allocating resources. Both institutions share many similarities; they offer international business programs delivered in English, and have comparable student numbers, gender, ethnicity and age - hence the creation of the partnership. However, neither institution currently has a ‘technology plan’ outlining how to integrate digital technology into traditional learning. Based on the matrix put forward by [59], both institutions can be described as representing the traditional classroom, thus efforts aimed at incorporating technology into teaching need to focus on introducing collaborative learning, in-class demonstrations, encouraging practical experience (especially with simulations), the use of software applications, plus access to course materials online. This enquiry does not set out to obtain, directly, insight into why technology-led learning has not been more widely adopted by either institution. However, by researching the challenges faced by the early adopters of technology, it is anticipated that the findings from this study might indirectly provide information to shed light on this crucial question.

Methodology

The methodology is structured in three phases. In the first phase,

documentary sources are used to explore the higher education

environment, technological considerations from a cross-cultural

perspective, specific national contexts and so on. In the second

phase, direct observations are undertaken during site visits in order

to collect information about the culture of the Russian institution

and the French institution, and their capacity to use technology-led

learning. The authors compiled notes which were then compared

so that information could be gathered and presented. In some

cases the information gathered provided a general picture of the

institutions that would complement data retrieved in the second

phase and, in other cases, to enhance data obtained. In the third and

final phase, face-to-face interviews are conducted between January

and March 2013 with teachers in each institution. The institutional

illustrations were not produced with the intention of generalizing

across different national contexts; they provide a modest snapshot

at a moment in time of the extent to which different institutions

have integrated technology-enhanced learning.

The sample was selected through institutional networking. As

the studies of Milroy and Milroy [60] have shown, people respond

more positively and in a natural manner when they are part of a

social or professional network. Further to this, the work [61-

65] strongly suggests that an auto ethnographic focus, including

participant observation, supports a conjoint approach which

increases critical depth and reflection in qualitative research. Using

a similar approach and for reasons similar to case, a very limited but expert population to sample from, a modified Delphi technique

was used to develop the semi structured interview topics. For these

reasons, the sample was composed of teachers from each institution

who are responsible for delivering the international business

programme to a cohort of circa 100 students. Teachers were invited

by email in December 2012 to participate in the investigation and

share their experience of using technology for teaching. In total, 21

individuals aged between 25 and 73 years old came forward to be

interviewed; 5 male and 5 female in France, 4 male and 7 female in

Russia.

Although total anonymity was guaranteed, over two-thirds of faculty involved in the delivery of the international programme declined to participate. Recruiting interviewees was equally difficult in Russia and France; partly because faculty lack time or interest to discuss such issues, partly because faculty lack skills to use the technology, or so it seemed. Others refused adamantly to comment on why they preferred not to be interviewed; some implied that they were concerned about repercussions from management. These behavioural traits are also noted in the observations of Lewis [66-70] who finds similarities between Russia and France in their traits of caution, reticence and unwillingness to compromise; both countries “think big and consider they have an important role to play” (p. 233). Given the exploratory nature of the study and the sample size, face-to-face open-ended interviews were chosen to investigate the use of technology for teaching. This technique provides ample opportunity to collect information on underlying ideas, prejudices and attitudes without needing to [71-76]. Five broad questions were designed to gather qualitative information about people’s online activities. It was anticipated that each interview should take 45-60 minutes to administer, allowing teachers sufficient time to express themselves freely. The questions were asked by the authors in the native language of the country in order to encourage ease of expression, focusing on the following specific details: motivation for integrating technology into teaching, initial feelings of using the technology, current use, positive and negative aspects, and any aspects that the respondent would prefer NOT to perform using the technology.

The responses given in the interviews were transcribed then coded according to the various words, phrases and sentences used by the participants to describe their experience of using technology for teaching. Acknowledging the work of Basic [77,78] which emphasizes the intuitive dimension of qualitative research, the initial analysis of the data was undertaken by the researchersinstead of electronically-in order to gain a deeper understanding of the situation and to continually refine interpretations. The data were then entered into Sphinx Lexica to check for any further interpretations. Following the analysis of the interview data, a forum was organised to take place in June 2013 in order to present the results of the investigation and to give the respondents in each location (Russia and France) an opportunity to comment on the findings. The forum was attended by respondents and some of their colleagues (n=36 in Russia and n=35 in France) who had not participated in the original interview but who were directly and indirectly involved with implementing innovative pedagogy. The purpose of including this phase of data collection was to further enhance the methodological approaches of [79-83]-and thus provide a more accurate and timely insight into engaging in digital technology.

Findings

It is acknowledged that the results of the enquiry are insufficient for generalizing; however they provide an insight into the various challenges faced by faculty who engage in technology-led learning. There is no ‘quick fix’ solution, as the findings will demonstrate. What distinguishes this case from others is the observation that the integration of new technology seems to be hindered by not only culture (national and organisational) but also by a vast array of complex factors including the awareness and perception of innovation, media ‘spin’, lack of confidence, legacy systems, timing and the need for staff to be steered by senior management. Overall, it seems that there is little knowledge or willingness to learn about using technology-led learning. In this predominantly conservative setting, incremental change may not be the answer for integrating technology-led learning; a brutal break with the past-a ‘revolution’ of sorts-may be the only viable solution to jumpstart technology-led learning through innovative pedagogy. Initial observations in each institution reveal commonalities concerning the faculty, students and attitudes to technology in general. Both the Russian and the French institutions seem to be struggling with the same issues regarding implementing new technology. For example managers, support staff and teachers are having trouble dealing with the (lack of) user-friendliness of the institution’s platform which is perceived as very cumbersome to navigate and manoeuvre, prompting teachers to explore alternatives for communicating with students online such as social networks. Attitudes towards using the institution’s platform are far from homogenous. In the Russian institution, it was observed that Moodle is used by some teachers for posting materials but perceived as an optional facility. Faculty mostly deliver oral lectures and some teachers now use PowerPoint. Students have to attend lectures. The requirement to be present in class conjures up a surreal image: while the lecturer speaks and writes on the board, the students are physically present but mentally engaged with their I-phones and laptops, giving the impression that they have disconnected from the class in favour of their virtual world. Similarly, student attendance is also mandatory in the French institution; classes are mostly taught using PowerPoint and the slides are usually (but not always) posted on the e-campus. There is a certain reticence surrounding the volume of academic materials that faculty are prepared to share on the e-campus. A revised version of the platform Spiral was launched in September 2012 but remains largely unknown and unused by the majority. Students still request information by email in preference to any other mode of communication. Laptops are generally not allowed in class but many teachers tolerate them rather than challenge the students. These observations call into question the degree to which technology-led learning should and could be introduced. The experience with Spiral provides little incentive for further investment in new technology.

Several dominant themes emerged in discussions with participants; key successes, greatest challenges, teacher learning (i.e. skills, knowledge, resources, how teachers used new technology to change classroom practice), benefits for students, and areas that need strengthening. These themes were common across both locations. Comments raised by participants show strong signs that the adoption of technology-enhanced learning is not universally embedded; for example “younger teachers took effort and learned to use it, 15-20% of teachers, they like it. Most people in the department don’t use: too time consuming, a lot of additional work; suspicious about control - it’s easy to see how often the teacher visits the platform-it’s ‘like prison’. Nobody is doing online-learning” (53 year old female tutor in Russia), and “I was pushing materials - articles, videos, slides - towards the students, trying to initiate a dialogue. The platform’s features matched my expectations; however, students’ involvement did not” (46 year old male tutor in France).

The responses given in the interviews support the data retrieved from direct observations that despite the availability of Moodle (Russia) and Spiral (France), less than 5% of faculty have adopted the platform for teaching. In other words, the introduction of a platform did not trigger a spontaneous uptake. Respondents spoke of low attendance at the training sessions. It seems that instead of the platform, faculty have opted for using various popular online sites and tools to communicate interactively with students. Moreover, the minority of respondents who currently make use of technology for teaching claim to be self-taught, suggesting that the use of technology can be described in terms of a personal objective rather than an institutional objective. It can be deduced that lack of interest and lack of technical skills may explain the low uptake of the institutional platform. The need to modernize teaching methods is uppermost in many responses, “organizations are more advanced, already using online workflows and we need to teach such skills to our students. All the graduate schools are initiating online learning programs and we have to compete” (51-year-old male tutor in France) and “make material more easily upgradable, make communication and control easier. It’s just more modern and fancier. They use it abroad” (27 year old female tutor in Russia). Paradoxically, participants made no connection between adopting technology and modernizing learning. This is one of the key findings of the investigation. A second observation was that faculty in the French institution share a common ‘positive’ approach to using technology-particularly social media-for teaching, underscoring the advantages of greater flows of information and communication.

Participants reported a broadly successful experience of interacting with students, once the initial technical problems were resolved, “The resources present information in a novel way; the students perceived the tutor as trying to be ‘modern’ in the teaching approach! Much more information (and updated information) can be accessed using online resources” (33 year old female tutor in France) and “Students were very enthusiastic; they really really liked it because they had no idea that podcasts could be used for practising these skills … very few knew JING. None used MAILVU. In the end the students decided that they would use these tools for other purposes” (54 year old female tutor in France). However, in the Russian institution the responses were less ecstatic about integrating new technology, describing it as “hardly combinable with our education process” (70 year old male tutor in Russia) and “require additional knowledge, trainings, seminars; teachers are afraid of additional work for the same salary, actually very small” (73 year old male tutor in Russia). It seems that the adoption of technology is neither influenced by gender nor culture; however there are strong signs that there is a generational issue in Russia.

Other comments suggest that younger staff are less conservative, such as “I am optimistic. But I have to do it anyway. 50% of staff use now. I post texts online which are already published to keep IP safe” (25 year old female tutor in Russia) and “The staff feel that new technology would be another burden. Younger teachers started immediately using it, sometimes without any sense, just to show how modern they are” (25-year-old female tutor in Russia). These responses illustrate the latent discontent that the platform in the Russian institution is available only for faculty under the age of 45; it is the unwritten assumption by management that older faculty are expected to retire around 55-60 years old and are therefore unable to provide a sufficient return on investment. Moreover, older staff are much less likely to use new technology in the classroom, compared with younger staff who are familiar with modern ICT.

The final observation was that participants recognized the time-saving aspects of interactive technology but raised concerns about three ongoing issues; ‘setting the tone’ for the correct use of the technology, the infrastructure that needs to be in place for faculty to adopt technology for teaching, plus the need to continue teaching basic skills - reading, writing, communication and analysis. The following comments illustrate their concerns “it is more workload than in the past. I really face resistance to change from students. I hope that the new version of Spiral will be more attractive for students” (51 year old male tutor in France) and “Skeptical – if Moodle is intensively used, the students will stop attending classes which will lead to lower quality of education” (39 year old female tutor in Russia). Participants voiced concerns that students need to be able to use the technology intelligently and critically in order to succeed in today’s workplace. The technology is not to be considered as a finite entity; it needs to be integrated into the specific culture of each institution. When discussing the limitations of using technology for teaching, various comments were put forward by participants to describe the frustration caused by technical problems: “with each new innovation, the chance of things going wrong multiplies” (41 year old female tutor in France) and “difficult to use, too much effort” (55 year old female tutor in Russia). The tutor is often left to resolve time-consuming issues such as computer access, log-on, broadband problems, forgotten passwords and so on. Another issue is that students are not as techno literate as they would like to appear. There is the risk of overestimating their ability and resources.

These comments highlight some of the obstacles and concerns experienced by faculty. In the cultural context of French higher education, there is the factor of uncertainty avoidance to be taken into consideration too. Culturally, there is a low tolerance to risk taking; any uncertainty is avoided. This reticence is also present in Russia but to a lesser extent. By far the biggest hurdle will be to transform the pedagogical culture and then build trust in a new learning approach. Students need to learn how to take responsibility for learning and sharing information among peers. Teachers need to relinquish direct control in order to build learning communities. New technology in education calls for a new philosophy of teaching; it represents a different way of thinking for many teachers in Russia and France.

In the analysis of the interview data, no specific words or phrases were frequently repeated but the general impression is that the perception of technology-led teaching is very individual, and often influenced by past experience of ICT and awareness of new technology in education. The summary of key interview data (in Appendices 1) reflects the complexity of implementing new technology in education, creating challenges at different levels across the institution. More research is needed, particularly research with a wider population involving student comments. What can be said so far is that faculty need to be convinced of the benefits of using digital technology for teaching; they are unlikely to adopt technology in response to a trend, however global the trend may be. Both faculty and students will only adopt new tools if they perceive them as being useful and meaningful for the task at hand.

One of the most striking observations is the fact that respondents

in France preferred to invest time in developing resources using

social media, blogs and wikis - rather than adopting the school

platform Spiral which was described as being ‘cumbersome’ and

‘not ergonomic’ by certain respondents. These findings suggest

that there is a willingness to try new technology that has been tried

and tested-such as social media-in preference for the technology

that has been installed. However, in Russia, the most surprising

observation was the attitude expressed by respondents that if

additional money was offered for implementing the platform into

teaching, then every teacher would use it, despite the fact that most

people think it is not compatible with traditional pedagogy and the

calibre of current students enrolled. Above all, it is highly unlikely

that a teacher would ever post un-published or updated materials

onto the platform for fear of plagiarism, irrespective of attractive

incentives such as additional payment. During the interviews,

several participants in each institution used this opportunity

to discuss the wider pedagogical issues of using technology for

teaching. Topics mentioned included; should teachers deliver what

they think today’s students expect-interacting through social media

- or should students be trained in the basic skills that they seem

to no longer master, such as listening to a person, understanding

human interaction, focusing attention and gathering information

they hear (not only read), being able to speak and discuss face-toface,

etc.? How can teachers design curricular to deliver the right

balance of basic and technical skills in order to produce active

citizenship and employable graduates? While this enquiry did not

set out to provide solutions to such issues, these questions reflect

mounting concerns about contemporary learning styles. These

attitudes reflect common concerns felt by faculty at both institutions

regarding the impact of technological change in education. A

number of factors need to be in place to facilitate the adoption of technology-namely adequate training, sufficient technical support,

and remuneration for developing new materials. Technology can

certainly enhance learning and provoke homogeneity in teaching

practices by reducing some of the cultural differences and language

barriers, but much work needs to be done to change attitudes,

pedagogical approach, management thinking-before technology

can be used to develop resources that can be shared across an

international partnership.

These views are substantiated by research undertaken in

Anglo-Saxon institutions; the work of [84-87] investigating online

learning communities in Open University, UK, found that the key

challenges to introducing new technology in education can be

“summarised under the following headings: costs; intellectual

property rights; custom and practice; and preconceptions and

perceptions”. [88,89] comment on the “need to integrate the online

aspects of the curriculum with the face-to-face elements”, pointing

out that “given the preponderance of generic US based simulations

in the Australian market, this is a very significant issue”. comment

on the dynamic nature of today’s learning communities, “blended

learning method continuously changes the ways of learning method

and technological infrastructure”-change on this scale requires

a somewhat flexible culture. The impact of culture (national and

corporate) plays a major role in international higher education,

thus highlighting the need to develop a strategy for the adoption

of technology-led learning at a local level for each institution. It is

necessary to acknowledge the various barriers (and others issues

raised) prior to being able to fully engage in digital technology for

learning.

The results of the investigation were presented at a forum held

in each institution in June 2013. The aim was to solicit qualitative

feedback, and also to see if there was any change in attitude

towards technology sine the interviews. The general feeling in

both locations was that the use of technology in higher education

should not undermine or be detrimental to the acquisition of

basic skills, in particular reading, writing, communication and

analysis. Technology needs to be kept in perspective, as a tool to

enhance learning. Teachers felt that the role of the institution is to

deliver more than mere academic facts; students need to develop

their interpersonal skills. For this reason, teachers need to make

every effort to ensure that students are able to use the technology

intelligently and critically in order to succeed in today’s online,

global workplace. Teachers maintain that technology is not to be

considered as a finite entity; it needs to be carefully integrated

into the culture of the institution in order to not lose sight of the

basic fundamentals of higher education. Respondents reiterated

the importance of providing teachers with sufficient training to

use the technology reflectively and to be able to pass those skills

on the students. One of the problems in higher education today

seems to be that many staff belong to the generation of so-called

Digital Immigrants - struggling to incorporate new technologies

into their own workplace and therefore not in a position to be able

to offer students what they need in terms of reflective digital knowhow.

Discussing the limitations of using technology, one teacher

(who wishes to remain anonymous) put forward that “everything

is possible online but it is fast becoming a question of ‘the more facilities added, the more the likelihood of things going wrong’.

With the best will in the world, problems cannot be anticipated.

In a student group, there’s always a problem to solve ... PC access,

logging-on, broadband issue, forgotten passwords and so on.

The tutor becomes the focal point for all student questions

(academic or technical)...this is one of the biggest drawbacks for

e-learning. Plus, this year we didn’t have enough online students

to offer the e-learning course at all. Fixing the technical problems

is very time-consuming even when there is a dedicated team for

technical support because the students turn to the tutor first, only

contacting IT support staff when the tutor cannot solve the problem.

The online course has to be planned and delivered at the speed of

the lowest-common denominator (many students are not as techno

literate as they would like to appear), to reduce the risk of them

getting left behind.” The above mentioned points have been taken

into consideration when drawing up a list of recommendations.

Conclusion and Implications

The investigation gathered data from a Russian institution and a French institution to explore how technology is used in teaching within an international higher education partnership; the findings reflect not only the impact of culture on technology awareness and technology acceptance, but also the barriers generated by management style and historic factors. There was no apparent change in attitude to technology-led learning when a forum was conducted after the interviews were administered. It is clear that technology is not being used to its full potential in learning communities. Although modern technology provides scope for truly collaborative work (notably academic research and cocreating teaching materials), it seems that teachers and students are underutilising the resources available, suggesting that there is a lack of awareness, lack of knowledge, lack of incentive to learn and/ or lack of willingness to adopt new technology.

Given the responses gathered in the interviews and from the forum, it is clear that ‘one size does not fit all’, judging from the range of technological tools cited in the interviews. The findings point to a number of issues that need to be considered prior to raising awareness of technology-led learning and for encouraging people to use it. In particular, the two most frequently cited issues seem to be ‘building trust’ and ‘acquiring technical skills’, but also ‘financial incentives’ to implement new teaching methods and ensuring ‘data protection’. Respondents took the time to voice their concerns about the security of information online, particularly information that has not yet been published and could theoretically be plagiarized by another colleague. Faculty need to feel reassured that the materials they place online will be safe, inferring that greater trust needs to be established. The spirit of ‘sharing knowledge is power’ is perhaps not as widespread as technology enthusiasts would like us to believe. The fact that such as small proportion of teachers claim to use the school platform (Moodle and Spiral) indicates that there are further barriers to using this type of technology. These barriers include the effort required to master a new way of delivering academic information plus the sheer volume of work required to convert current teaching materials into the correct format to use on the platform, not forgetting the opportunity cost - in other words the time spent learning new skills and developing compatible materials means that other areas of academic work are being neglected. For this reason, several teachers have avoided the challenge of learning how to use the pedagogical platform provided by the institution - in favour of exploiting popular, user-friendly technology such as Jing, MailVu, Scribd and Dropbox. Various other reasons were given for the slow uptake of technology including the need for round-the-clock technical support, additional training in technical skills and financial recognition for adopting new tools. These responses underscore the huge investment that is required to bring about change in the teaching culture; not merely a change in methodology but also a change in mentality. Change on this scale is highly complex and influenced by many peripheral factors; for example, it is likely that level of education and teaching experience can account for the slow adoption of technology or in some cases, the non-adoption of technology. Installing new technology is not enough to make people want to try it. Even when the technology is freely available, faculty need to be nurtured into testing out new methods of teaching.

Bearing in mind the original intention of this enquiry which was to explore the extent of technology-led teaching in Russia and France (in order to raise awareness), the results show strong signs that efforts need to be concentrated in three areas: firstly, developing a positive attitude towards using new technology; secondly, reassuring users of data protection; lastly, building trust between users. To raise awareness of technology-led learning, these efforts need to be both top-down (commitment form senior managers) and bottom-up (incorporating ideas from users: faculty and students). Acquiring a positive experience of using new technology is vital for the effective dissemination of good practice amongst faculty at both the Russian institution and the French institution.

More research however is needed to understand the evolution of technology usage in international education. Continuing this enquiry, the next step is to investigate faculty who have chosen not to use the technology, looking at factors that hinder technology adoption in order to put forward a strategy to raise awareness; then to explore student experiences of technology-led learning. In the forum, respondents confirmed that many students still want to be taught face-to-face using traditional teaching methods, even though (paradoxically) they are heavy Internet users. Students enjoy using interactive tools for sharing information with others and they expect Internet access on campus 24/7-but given the choice, many students appear to prefer more traditional methods to 100% online learning. We acknowledge the progress and enormous efforts that have been made in different institutions over the past decade to implement technology-led learning. Taken against the theoretical background, we conclude that a different approach is needed at each institution to reflect the local context.

Appendices 1: Good practice guidelines for implementing technology-led learning

Given the cultural context of the investigation, the following recommendations have been drawn up to reduce the disruption that could be caused by introducing new technology.

Strategy: The first step is to define a precise idea of what constitutes technology-led learning; for students, teachers and support staff. People need to know what the technology can do and how it can help them. Senior management needs to acknowledge that online learning is not a cost-cutting initiative and more importantly that it is a two-way medium, necessitating interactivity from all users. A successful and sustainable initiative requires committed resources; financial investment in time, technology, staff development and student support. Users (and stakeholders) need to be informed of the introduction of technology by official communication channels (posters, email, internal events to demonstrate the benefits of the new software, etc.). The message must be clear, coherent and consistent to all users; therefore several different pitches of the same message will be necessary.

Online tools: The institutions need to set up a VLE (a virtual learning environment) that is simple and easy to navigate. The learning platform should offer a wide selection of web 2.0 tools to enhance the learning experience for students (some of whom may have had very little exposure to ICT) and to prepare them for today’s information society. Management need to understand the cost involved; installation, training, support, etc.-and perhaps obtain a trial version to install and test before buying. The provision of multilingual content needs to be taken into account for international students. It is equally vital to implement a single VLE where students can find all the information they need and where they can communicate and collaborate with the course material and other students.

Technical support: For a successful transition, school management must ensure that the institution’s infrastructure can cope with widespread adoption and use of online learning. This mandates adequate technical support (ideally 24/7) as well as a designated ‘trouble shooter’ on site to manage the whole operation.

Pedagogy: It is important for management (and teachers) to recognize that online teaching does not equate to replicating offline materials online. It would be constructive to provide examples of institutions throughout the world that are currently using technology-led teaching methods. From a communication point of view, the institution will need to develop a handbook (code of conduct, standards and principles) for staff to follow in order to ensure quality and consistency in their innovative pedagogy.

Staff development (Sd): The implementation of technology in learning mandates a robust SD program to enable staff to be able to deliver the type of quality online learning that can enhance the student learning experience. Management need to take into account the current level of digital literacy among its staff and then develop training accordingly. They also need to make sure that their SD program prepares staff in both the technology and the methodology of online learning - and that it does so in a way that is the most beneficial to staff. For this stage to be possible it would be constructive to begin by training the opinion leaders, change agents and technology enthusiasts - in the hope that they will encourage others to adopt. Realistically, it would be wise to start small and develop the program over time, addressing ‘snagging’ and other issues as they arise. Finally, the users (support staff and teachers) need to have a clear understanding of the institution’s goals concerning technology-led learning, and of their own individual responsibility vis-à-vis the new technology, in other words, what the institution expects of them and how they will deliver.

Compensation: School management must accept the constraints of implementing new technology for learning, in terms of time, money and effort. SD is one issue; student support is another. This is an important point because the success of the learning platform depends on a complete understanding and adoption of the new technology by all users. Some universities charge more for their online classes to cover the costs of providing the necessary student support. With this in mind, the institution has to be prepared to offer some sort of compensation to the staff involved in technologyled learning. This can take the form of lessening their teaching load or administrative role - to allocate time for developing new resources. Financial incentives or career advancement can also be offered. Avoiding reward and recognition could damage the success of implementing technology-led learning.

Consequences: If an institution postpones the technologyled initiative then it runs the risk of losing students to institutions that have already made the transition. Students are increasingly looking for institutions that offer well-developed technologyenhanced education programmes that will prepare them for careers in today’s information society. Given the comparatively slow adoption of online education in Russia and France, the time is right to take the initiative and become an early adopter. Moreover, the technology could play a major role in the modernisation and internationalisation of the institution, attracting teachers and students from across the globe. It could also attract new strategic partners to strengthen the network of businesses who work with both institutions on a number of projects.

References

- Ardagh John (1987) France Today. Penguin: London.

- Babkin Alexander, Khvatova Tatiana (2009) Development of the research sector in the NIS of Russia, News of St. Petersburg State University of Economics and Economics 4: 41-50.

- Bain Olga, Zakharov Iouri, Noosa Natalia B (1998) From centrally mandated to locally demanded service: the Russian case. Higher Education 35(1): 49-67.

- Bandura A (1975) Social Learning & Personality Development. Winston, USA.

- Barsoux JL, Lawrence P (1997) French Management, Taylor and Francis, Oxford.

- Batjargal Bat (2007) Comparative social capital: Networks of entrepreneurs and venture capitalists in China and Russia. Management and Organization Review 3(3): 397-419.

- Batjargal Bat, Hitt Michael, Webb Justin, Arregle Jean Luc, Miller Toyah, et al. (2009) Women and Men Entrepreneurs’ Social Networks and New Venture Performance Across Cultures Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings. Journal of human science p: 1-6.

- Basit Tehmina (2003) Manual or electronic? The role of coding in qualitative data analysis. Educational Research 45(2): 143-154.

- Beerkens Eric (2008) University Policies for the Knowledge Society: Global Standardization, Local Reinvention. Perspectives on Global Development & Technology 7(1): 15-36.

- Bell Jane (2007) E learning: your flexible development friend? Development and Learning in Organizations 21(6): 20-50.

- Bold Mary, Chenoweth Lillian, Garimella, Nirisha (2008) BRICs and Clicks. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 12(1): 5-25.

- Brennan John, King Roger, Lebeau Yann (2004) The Role of Universities in the Transformation of Societies-An International Research Project: Synthesis Report, Association of Commonwealth Universities/Centre for Higher Education Research and Information, Open University, London.

- Burawoy, Michael (2001) Neoclassical Sociology: From the End of Communism to the End of Classes. American Journal of Sociology 106(4): 1099-1120.

- Chang Ting Ting, Lim John (2002) Cross-cultural communication and social presence in asynchronous learning processes. e-Service Journal 1(3): 83-105.

- Cheng YC, Tam MM (1997) Multi models of quality in Education. Quality Assurance in Education 5: 22-31.

- Chizmar, John and Williams, David (1996) Altering Time and Space through Network Technologies to Enhance Learning. CAUSE/EFFECT Fall pp: 14-21.

- Chou Amy Y, Chou David C (2011) Course Management Systems and Blended Learning: An Innovative Learning Approach. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education 9(3): 463-484.

- Cornuel E (2007) Challenges facing business schools in the future. Journal of Management Development 26(1): 118-126.

- Craft M A, Carr R B, Fund Y (1998) Internationalization and distance education: A Hong Kong case study. International Journal of Educational Development 18(6): 31-89.

- De Witt H (2002) Internationalization of Higher Education in the United States of America and Europe. Greenwood, Westport.

- Dobbins Michael, Knill Christophe (2009) Higher Education Policies in Central and Eastern Europe: Convergence toward a Common Model? Governance 22(3): 397-430.

- Eringa Klaes, Huei Ling Yu (2009) Chinese Students’ Perceptions of the Intercultural Competence of Their Tutors in PBL. In: D Gijbels, P Daly (Eds.), Advances in Business Education and Training: Real Learning Opportunities at Business School and Beyond 2: 17-37.

- Fava De Moraes F, Simon I (2000) Computer networks and the internationalization of higher education’. Higher Education Policy 13: 319-324.

- Fleck J (2008) Technology and the business school world. Journal of Management Development 27(4): 415-424.

- Fleck J, Howells J (2001) Technology, the technology complex and the paradox of technological determinism, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 13(4): 523-531.

- Fleck J (2012) Blended learning and learning communities: opportunities and challenges. Journal of Management Development 31(4): 398-411.

- Garrison Randy, Anderson Terry (2003) E learning in the 21st Century: A Framework for Research and Practice. New York, USA.

- Gergen K, Gergen M (2007) Social Construction and Research Methodology. In: W Outhwaite, S Turner (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Social Science Methodology. Sage Publications, London pp: 461-478.

- Gill Jas, Butler Richard (2003) Managing instability in cross-cultural alliances. Long Range Planning, 36(6): 543-563.

- Gronennings S (1997) The Impact on Economic Globalization on Higher Education, Boston: New England Board of Higher Education.

- Halal William (2008) Online learning systems: highlights of the TechCast project, The journal of information and knowledge management Systems 38(2): 198-205.

- Han Jin K, Chung Seh Woong, Sohn Yong Seok (2009) Technology Convergence: When Do Consumers Prefer Converged Products to Dedicated Products? Journal of Marketing 73(4): 97-108.

- Best Practices for Integrating Technology into the Classroom. (2009) Hanover Research Council Washington, USA.

- Hiltz Starr Roxanne, Turoff Murray (2005) Education goes digital: The Evolution of Online Learning and the Revolution in Higher Education. Communications of the ACM 48(10): 59-64.

- Hofstede Geert (1993) Cultural constraints in management theories. Academy of Management Executive 7(1): 81-94.

- Hwang Alvin, Francesco AnneMarie (2010) The Influence of Individualism Collectivism and Power Distance on Use of Feedback Channels and Consequences for Learning. Academy of Management Learning & Education 9(2): 243-257.

- Jiang Xiaoping (2008) Towards the internationalization of higher education from a critical perspective. Journal of Further and Higher Education 32(4): 347-358.

- Jones Norah, Lau Alice (2010) Blending learning: widening participation in higher education, Innovations in Education and Teaching International 47(4): 405-416.

- Khvatova Tatiana (2011) Institutional mechanisms for implementing innovation in the national economy. St Petersburg: Polytechnic Publishing House University pp: 1-166.

- King Roger (2010) Policy Internationalization, National Variety and Governance: Global Models and Network Power in Higher Education States. The International Journal of Higher Education and Educational Planning 60(6): 583-594.

- Kolb DA (1984) Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall 8(4): 359-360.

- Kortunov Andrei (2009) Russian Higher Education. Social Research 76(1): 203-224.

- Krakovsky Marina (2010) Degrees, Distance, and Dollars, Communications of the ACM 53(9): 18-19.

- Kryshtanovskaya Olga, White Stephen (1996) From Soviet Nomenklatura to Russian Elite. Europe Asia Studies 48(5): 711-734.

- Lane, Peter, Salk Jane, Lyles Marjorie (2001) Absorptive capacity, learning, and performance in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal 22(12): 1139-1161.

- Leitch Review of Skills (2006) Prosperity for all in the global economy-world class skills, HM Treasury on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, England.

- LEWIS R (1997) When cultures collide. Nicolas Brealey Publishing Ltd, London.

- Lichy Jessica (2012) Towards an International Culture: Gen Y Students and SNS? Active Learning in Higher Education 13(2): 101-116.

- Little Brenda, Williams Ruth (2010) Students' Roles in Maintaining Quality and in Enhancing Learning: Is There a Tension? Quality in Higher Education 16(2) : 115-127.

- Magun Artemy (2009) Léducation supérieure dans la Russie post soviétique et la crise mondiale des universités, Observations de l'intérieur, Multitudes 4(39): 109-120.

- Malhotra N (2009) Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, New York, Pearson.

- Martin Bill (2005) The Information Society and the Digital Divide: Some North South comparisons. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology 1(4): 30-41.

- Mason R (1998) Globalising Education, Trends and Applications, London.

- McCombs Barbara, Vakili Donna (2005) A learner centered framework for E learning. Teachers College Record 107(8): 1582-1600.

- Menesr (2006) Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. Les établissements d’enseignement supérieur: Structure et fonctionnement.

- Milroy Leslie, Milroy James (1992) Social network and social class: Toward an integrated sociolinguistic model. Language in Society 21(1): 1-26.

- Mitry Darryl J, Smith David E (2009) Convergence in global markets and consumer behaviour. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33(3): 316-321.

- Naszalyi Philippe (2010) De nouvelles ressources pour l'entreprise, La Revue des Sciences de Gestion, Direction et Gestion 242: 1-5.

- O'Connor Christine, Mortimer Dennis Bond Sue (2011) Blended Learning: Issues, Benefits and Challenges. International Journal of Employment Studies 19(2): 62-82.

- OECD (2004) Policy Brief: Internationalization of Higher Education Paris.

- Ofer Gur, Polterovich Victor (2000) Modern Economics Educations in TEs, Comparative Economic Studies 42(2): 5-35.

- Onsman Andrys (2008) Tempering universities’ marketing rhetoric: a strategic protection against litigation or an admission of failure? Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 30: 177-85.

- Panova, Alexandra (2008) Governance Structures and Decision Making in Russian Higher Education Institutions, Problems of Economic Transition 50(10): 65-82.

- Paquette Emmanuel (2012) Faut il réguler Internet. L’Express, 1 Février 31: 6168-6169.

- Punie Yves (2007) Learning Spaces: an ICT-enabled model of future learning in the knowledge-based society. European Journal of Education 42(2): 185-199.

- Ramirez Jacobo, Fornerino Marianela (2007) Introducing the impact of technology: a ‘neo-contingency’ HRM Anglo-French comparison, International Journal of Human Resource Management 18(5): 5924-949.

- RECEP: Russian European Centre for Economic Policy (2005) The Bologna Process and its Implications for Russia, Moscow.

- Rex E (2010) Social media burst into Europe’s B schools, Bloomsburg Business USA.

- Richmond A S, Cummings R (2005) Implementing Kolb’s learning styles into online distance education. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning 1: 145-154.

- Rienties Bart, Grohnert Therese, Kommers Piet, Niemantsverdriet Susan, Nijhuis Jan (2011) Academic and social integration of international and local students at five business schools, a cross-institutional comparison. In: P Van den Bossche, WH Gijselaers, RG Milter (Eds.), Building Learning Experiences in a Changing World, USA, 3: 121-137.

- Ritchie C (2005) Identifying the UK Wine Consumer. University of Wales Institute Cardiff, UK.

- Saadi S (2011) B-schools are all a-twitter over social media, USA.

- Saginova Olga, Belyansky Vladimir (2008) Facilitating innovations in higher education in transition economies. International Journal of Educational Management 22(4): 341-351.

- Schepers Jeroen, Wetzels Martin (2007) A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model; investigating subjective norm and moderation effect. Information and Management 44(1): 90-103.

- Skidmore David, Marston Jan, Olson Gretchen (2005) An Infusion Approach to Internationalization: Drake University as a Case Study. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad 11: 187-203.

- Sobaih AE, Ritchie C, Jones E (2011) Consulting the Oracle? Applications of Modified Delphi Technique to Qualitative Research in the Hospitality Industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management.

- Tempelaar Dirk, Rienties Bart, Giesbers Bas (2009) Who profits most from blended learning? Industry and Higher Education 23(4): 285-292.

- Timoshenko, Konstantin (2011) The Winds of Change in Russian Higher Education: is the East moving West? European Journal of Education 46(3): 397-414.

- Timoshenko, Konstantin, Adhikari P (2009) Implementing public sector accounting reform in Russia: evidence from one university. Research in Accounting in Emerging Economies 9: 175-198.

- Thomas M, Thomas H (2012) Using new social media and Web 2.0 technologies in business school teaching and learning. Journal of Management Development 31(4): 358-368.

- Tonks David (2005) The Processing and Pedagogy of Marketing Simulations. The Marketing Review 5(4): 371-382.

- Tungen A (1999) MIT and University of Cambridge Announce $135 million Joint Venture. The Cronicle of Higher Education p: 1-71.

- Ulhoi JP (2005) Postgraduate Education in Europe. International Journal of Education Management 19(4): 347-358.

- Verbitskaya Ludmila, Nosoca Natalia, Rodina Ludmila (2002) Sustainable development in higher education in Russia: The case of St Petersburg State University. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 3(3): 279-287.

- Vygotsky Lev (1978) Mind in Society. Harvard University Press, London.

- Walton John, Guarisco Gisèle (2008) International collaborative ventures between higher education institutions: a British-Russian case study. Human Resource Development International 11(3): 253-269.

- Westwood S (2005) Narratives of Tourism Experience: an Interpretive Approach to Understanding Tourist-Brand Relationships. University of Wales Institute Cardiff, UK.

- Windham DM (1996) Overview and main conclusions of the seminar. Internationalization of Higher Education, Paris: OECD.

- Wu Mingxuan, Yu Ping (2006) Challenges and opportunities facing Australian universities caused by the internationalization of Chinese higher education. International Education Journal 7(3): 211-221.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...