Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Case ReportOpen Access

Depression Revealing Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome with Neurological Involvement Volume 3 - Issue 5

Salem Bouomrani1,2*, and Ines Masmoudi1,2

- 1Department of Internal medicine, Military Hospital of Gabes, Tunisia

- 2Sfax Faculty of Medicine, University of Sfax, Tunisia

Received: April 17, 2020; Published: April 27, 2020

Corresponding author: Salem Bouomrani, Department of Internal medicine, Military Hospital of Gabes, Gabes 6000, Tunisia

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2020.03.000175

Abstract

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) is the most frequent connective tissue disease but remains very underdiagnosed. Psychiatric manifestations are classified among the central neurological disorders of pSS, and their prevalence is variously estimated according to the series and the recruitment services: 20-70% of cases. They may be the predominant manifestations of the disease, but pSS remains an underestimated cause of neuropsychiatric disorders. The inaugural psychiatric presentations of this disease are exceptional and represent a real diagnostic challenge for clinicians. We report an original observation of depression as an initial and isolated manifestation revealing neuro-Sjögren ina 60-year-old woman. Only a few similar sporadic cases were previously reported in the world literature. As rare as it is, this clinical presentation of pSS deserves to be known by any healthcare professional.

Keywords: Depression; Primary sjögren’s syndrome; Neurological involvement; Neuro-sjögren; Behavior disorders

Introduction

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) is an autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the exocrine glands and the production of autoantibodies, the most characteristic of which are anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies [1,2]. With a prevalence of 0.1- 3% and an incidence of 3.9-5.3 per 100,000, pSS is the most frequent connective tissue disease, but remains very underdiagnosed [3]. Systemic extra-glandular manifestations of this disease are rare (10- 15% of cases) but often serious and condition the prognosis [1,4]. The most frequent of these disorders including pulmonary, renal, neurological, and digestive [1,4]. These systemic manifestations are very polymorphic, heterogeneous, and non-specific, justifying the qualification of this syndrome as a “great masquerader” [5]. The specific neurological involvement of this disease (neuro-Sjögren) is not uncommon but very polymorphic and often under-diagnosed [3,6]. Depression, classified among the manifestations of central neuro-Sjögren (involvement of the central nervous system) [6,7] can be seen in 32 to 46% of cases [8]. The inaugural forms of the disease are exceptional and represent a real diagnostic challenge for clinicians [5]. We report an original observation of depression as an initial and isolated manifestation revealing neuro-Sjögren.

Case Report

A 60-year-old woman, with no notable pathological history, was explored for sadness of the mood with insomnia and permanent headache evolving for three months. She was initially referred by her family doctor to the psychiatric department where antidepressant treatment was prescribed. No improvement was noted after two months of well-observed anti-depressant therapy at optimal doses. The cerebral computed tomography as well as the basic biological investigations (total blood count, renal, hepatic, and thyroid tests) were without anomalies. The somatic examination at our consultation noted dry skin, a fissured tongue, and a reflex quadripyramidal syndrome. No fever, disturbances of consciousness, skin lesions, lymphadenopathy, and visceromegalies were noted. Respiratory and cardio-circulatory status were preserved. Biology showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate at 56mmH1 and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia at 24g/l without other abnormalities (hemoglobin, leukocytes, platelets, C-reactive protein, calcemia, creatinine, transaminases, uric acid, muscle enzymes, plasma ionogram, glycemia, lipid parameters, and thyroid hormones).

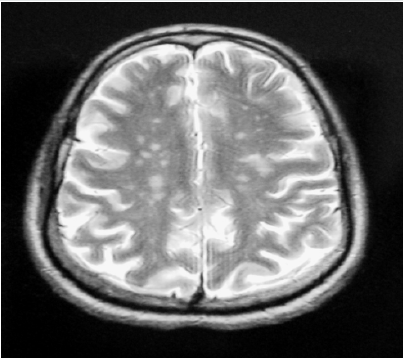

The ophthalmological examination revealed bilateral keratoconjunctivitis with positive Schirmer’s and a breakup time tests. The labial minor salivary gland biopsy showed focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis with a focus score at 2. The immunological tests objectified positive anti-nuclear, anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed multiple lesions of the periventricular deep white matter and centrum ovale, in T2 and FLAIR hypersignal, T1 hyposignal, and enhancing after Gadolinium injection (Figure 1). Lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid analysis were without abnormalities. Thus, the diagnosis of pSS with central neurological damage was retained according to the European classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome without clinical signs or immunological markers of other connective tissue disease. The anti-depressant treatment was stopped, and the patient was treated with three boli of methylprednisolone (1g/day) followed by oral corticosteroid therapy at a dose of 1mg/kg/day for four weeks. The evolution was favorable with disappearance of functional complaints and disappearance of depressive symptoms. The control brain MRI at six months of treatment was normal. Currently, and two years later, the patient is still stable without any psychiatric symptoms.

Figure 1: Axial T1-weighted brain MRI with injection: multiple hypersignals of deep periventricular white matter enhancing after Gadolinium.

Discussion

Neurological manifestations are variously estimated during

pSS depending on the series: 8.5-70% and are by far dominated

by peripheral neuropathies [3,6]. The central nervous system

involvement is much rarer with very polymorphic clinical aspects

[3,6]. Psychiatric manifestations are classified among the central

neurological disorders of this connective tissue disease, and their

prevalence is variously estimated according to the series and

the recruitment services: 20-70% of cases [9]. They may be the

predominant manifestations of the disease [9], but pSS remains

an underestimated cause of neuropsychiatric disorders [10]. The

clinical spectrum of psychiatric manifestations of pSS can include:

anxiety disorders, cognitive disorders, attempt to suicide/suicidal

ideas, psychotic disorders, auditory and visual hallucinations,

agitation/agitated behavior, aggression, paranoia, confusion,

emotional lability, depression/depressive disorder, anxiety

disorder, sleep disorder/insomnia, delusions, catatonia/catatonic

state, schizophrenia/schizophrenia-like symptoms, obsessivecompulsive

disorders, other personality disorders, and dementia

[3,6,11,12].

The pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders during

pSS is not yet fully understood. It appears to be multifactorial

involving diffuse central nervous system vasculitis, lymphocytic

inflammatory infiltration of nervous tissue, as well as an antibodyantigen

reaction between pSS autoantibodies and nerve tissue

antigens [6,9]. The exact prevalence of depression during pSS

remains unclear [8]. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Cui Y

et al, revealed that the prevalence of depression in patients followed

for pSS is significantly higher compared to the general population

(odds ratio at 5.36, p <0.01). Similarly, the depression scores in

pSS’s patients are higher than in the control group [8].

The Shen CC et al Nationwide Population-based Retrospective

Cohort Study enrolling 2,686 patients with pSS and 10,744

matched controls in Taiwan, objectified significantly higher

psychiatric disorders (depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and

sleep disorder) in subjects with pSS compared to healthy controls:adjusted hazard risk at 1.829, 1.856, and 1.967 respectfully [13].

Depression associated with pSS is characterized by its partial

response or resistance to specific anti-depressant drugs [3,10,11].

On the other hand, it usually evolves favorably under corticosteroids

[9], and sometimes immunosuppressants [9,12].

More rarely plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins

[12] and even biotherapy have been shown to be necessary to

stabilize these neuropsychiatric disorders [3]. Depression as the

first manifestation revealing pSS, as in our observation, remains

exceptional with only a few sporadic observations [3,9,10,12]. It

can be seen even in the absence of any specific dry syndrome of

the disease [3], be moderate or severe, isolated or associated with

other psychiatric disorders [3,10,12], and occur in young people

and adolescents making diagnosis more difficult [13]. Finally,

it should be noted that depression and in general psychiatric

disorders impact negatively the pSS-patient’s quality of life and the

outcome of their disease [8,14,15].

Conclusion

As rare as it is, this clinical presentation of pSS deserves to be known by any healthcare professional. The pSS remains an unexpected and under-recognized etiology of neuropsychiatric involvement, especially in young. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with new psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of sicca symptoms. Systematic neuropsychological tests may contribute to early detection of central nervous system damage during pSS, even in the pre-clinical phase. Only this early diagnosis will improve the prognosis of the disease.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Patel R, Shahane A (2014) The epidemiology of Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Epidemiol6:247-255.

- Sprecher M, Maurer B, Distler O (2020) Primary Sjögren's Syndrome - News on Diagnostics and Therapy. Praxis (Bern 1994) 109(5):333-339.

- Hammett EK, Fernandez-Carbonell C, Crayne C, Boneparth A, Cron RQ, et al. (2020) Adolescent Sjogren's syndrome presenting as psychosis: a case series. PediatrRheumatol Online J18(1):1-15.

- Demarchi J, Papasidero S, Medina MA, Klajn D, Chaparro Del Moral R, et al. (2017) Primary Sjögren's syndrome: Extraglandular manifestations and hydroxychloroquine therapy. Clin Rheumatol36(11):2455-2460.

- Kumar N, Surendran D, Srinivas BH, Bammigatti C (2019) Primary Sjogren's syndrome: a great masquerader. BMJ Case Rep 12(12): pii: e231802.

- Perzyńska-Mazan J, Maślińska M, Gasik R (2018) Neurological manifestations of primary Sjögren's syndrome. Reumatologia56(2):99-105.

- Margaretten M (2017) Neurologic Manifestations of Primary Sjögren Syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 43(4):519-529.

- Cui Y, Li L, Yin R, Zhao Q, Chen S, et al. (2018) Depression in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med23(2):198-209.

- Ampélas JF, Wattiaux MJ, Van Amerongen AP (2001) Psychiatric manifestations of lupus erythematosus systemic and Sjogren's syndrome. Encephale27(6):588-599.

- Rosado SN, Silveira V, Reis AI, Gordinho A, Noronha C (2018) Catatonia and Psychosis as Manifestations of Primary Sjögren's Syndrome. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med5(6):000855.

- Lin CE (2016) One patient with Sjogren's syndrome presenting schizophrenia-like symptoms. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat12:661-663.

- Ong LTC, Galambos G, Brown DA (2017) Primary Sjogren's Syndrome Associated with Treatment-Resistant Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Front Psychiatry8: 100-124.

- Shen CC, Yang AC, Kuo BI, Tsai SJ (2015) Risk of Psychiatric Disorders Following Primary Sjögren Syndrome: A Nationwide Population-based Retrospective Cohort Study. J Rheumatol42(7):1203-1208.

- Koçer B, Tezcan ME, Batur HZ, Haznedaroğlu Ş, Göker B, et al. (2016) Cognition, depression, fatigue, and quality of life in primary Sjögren's syndrome: correlations. Brain Behav6(12):e00586.

- Omma A, Tecer D, Kucuksahin O, Sandikci SC, Yildiz F, et al. (2018) Do the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Sjögren's syndrome outcome measures correlate with impaired quality of life, fatigue, anxiety and depression in primary Sjögren's syndrome? Arch Med Sci14(4):830-837.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...