Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research ArticleOpen Access

Art Therapy Group for Women who had been Sexually Abused in a Gallery Space During the Covid 19 Crisis Volume 7 - Issue 1

Einat Metzl* and Daphna Markman-Zinemanas

- Bar Ilan University, Israel

Received:December 19,2022; Published:February 06, 2023

Corresponding author: Einat Metzl, Bar Ilan University, Israel

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2023.07.000253

Abstract

This paper explores the rationale and process of offering an art therapy group for women who had been sexually abuse in a gallery space during the Covid19 crisis. The group was led by a trained art therapist who is also an active artist in Israel and a clinical social worker who works in the municipal clinic for the sexually abused where the group members have individual psychotherapy. This model is offered here with the hope of reflecting on the unique aspects of this work in a non-clinical, art based, setting.

Introduction

Art had long been understood as a uniquely human way of meaning making and communicating the essence of our experiences with one another [1]. Art Therapy, as a field, had emerged from the intersection of art education, art administration and the socio-psychological needs that were aided by therapeutic use of art [2] specifically around a growing recognition that the making of art, with a focus of the engagement in the process of art making, enhanced psychological wellbeing and, deepened communication around psycho-socio-cultural issues. Starting with the making of workshops for veterans in museums after the two world wars [2] the integration of art expression as a tool in progressive education [3] and a democratic tool self-expression where the experience is at the core [4]. Process Art and including Outsider Art as defining aspects of Modern Art [2] further postulated that engaging in art offers therapeutic and social gains [5,6] while establishing art therapy as a profession. In the US and Great Britain, for example, the use of art making with hospitalized psychiatric patients, children who have special educational and behavioral needs. veterans suffering from PTSD (originally offered as community service offered in museums), etc. set the stage [5,7]. The rise of psychoanalysis, with the understanding of art as tool for sublimation and insight (Freud) as well as a tool for expression, integration, and connection (Jung), all supported the growing definition of art therapy as a mental health profession [6].

The place of therapeutic use of art and other forms of art therapy that does not follow traditional psychotherapeutic setting and structure had grown dramatically over the last couple of decades with the development of models such as Open Studio approach [8- 10], the portable studio and inhabitable studio models [11,12], and the many uses of community-based work internationally [13,14], etc. The above approaches, especially over the last decade, often also carry a clear social-action and post-modern mission [14,15], and at times are reported as part of participatory action research [16]. In addition, continuing the legacy of pioneer artist and art therapist Edith Kramer [17] and art educator Florence Cane, programs and interventions at times developed as a meeting place between art therapy and art education [18,19]. Often through collaborations of artists, art educators, and / or art administrators with art therapists [18,19]. [20-22] to support communities in need. According to Hartman [23] when art therapists offer expressive interventions within museum settings, they are often referred to as Museum Based Art Therapy (MBAT).

Art Therapy in museums and galleries

Expressive interventions or workshops conducted within museums or galleries and facilitated by art therapists have also been an increasingly reported phenomenon over the years [23,24] In her research of art therapy within museum settings, [25] concluded that:

1) Museums can be effective allies in art therapy treatment.

2) Including artistic institutions honor origins, evolution, and role of art in art therapy

3) Logistics: space, artifacts, and duration are important in museum art therapy

4) The role museums play in art therapy: museum as co-leader, group, self, and environment.

5) Metaphorical roles of museums can facilitate treatment goals in life stage.”

Some examples of well-known art therapy work in museums, where the museum space and exhibition expand the therapeutic impact [26] include art therapy social action intervention for teens at risk in the Museum of Tolerance inspired by the work of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis [27], The Cancer Journey project [28] giving creative presence and voice to cancer survivors, survivors of eating disorders [29], in which creating art exhibit or visiting an art museum were integrated into art therapy treatment, or providing a therapeutic space for adults with intellectual and developmental impairments [30]. Another example includes the PleaseTouch / ArtAccess programs that originally served the visual impaired in the Queen’s Museum and now serve multiple communities inside and outside the museum of it through the collaborations of art therapists, artists, educators, and community leaders.

Art Therapy for women who had been sexually abused.

Art Therapy treatment and interventions have long been identified as a tool to support women who suffered sexual abuse [31,32] enhance resilience [33] reduce shame and stigma and shame, process trauma and increase self-compassion [34]. Because of the visual and sensory-motor impact of trauma on the survivors’ symptoms and because art offers an integrative and strength based, trauma informed tool, art therapy had long been accepted as an effective intervention [35]. Historically, when survivors of all ages turned to treatment but needed a less verbal, less linear, wholistic intervention, art therapy provided a uniquely prominent alternative to traditional talk therapy. Similarly, working with sexual abuse survivors in group settings offers a sense of community, validation and normalization which is an anthesis to the secrecy, shame, and isolation that many sexual abuse survivors endure. The patient has the choice to express herself non-verbally deeply through art. Thus, she can feel a sense of control over the therapeutic content and process, and yet being active and productive in relation to her traumatic past which was connected to passivity and helplessness [36]. In a group setting the art works can enhance communication, identification and mutual empathy and support. Group members can help and being helped which is a way of experiencing their strengths.

Art Therapy during the Covid-19 pandemic

The need for a community, combating isolation and anxiety, intensified over the Covid-19 pandemic [37], further increasing the call for art therapy groups, whether virtual or physical, local, or global [38]. Multiple art therapy clinics and programs now offer online art therapy treatment including group sessions [39]. In reviewing art therapy practice during the pandemic, much of the literature focused on the novel use of telehealth (online art therapy services) as a substitute to ongoing and incoming treatment. Therapists and researchers discussed some benefits to zoom mediated art therapy which often includes increased accessibility and comfort for clients, and particularly those coping with health, mental health, or geographic barriers to treatment. Art therapy publications also discussed the importance of the creation of community support and reducing isolation during the Covid-19 pandemic and suggested new ways to offer creative interventions which are either created at home from materials that clients have or utilizing digital creative apps. Discussions of limitations often focused on ethical and technical challenges related to zoom mediated art therapy, and the felt difference in offering materials and physical presence. However, very few publications explored the meaning of face-to-face meetings during the pandemic, an opportunity that was uniquely offered in Israel, where many clinical services remained face-to-face even during the pandemic, and as was possible with this unique group of women.

The aesthetic experience.

The main difference of MBAT in relation to traditional Art Therapy setting is the palpable presence of the exhibitions’ space and the artworks within it. The aesthetic experience in a gallery space can enhance patients’ own artistic expression. [40] related to the activity of the mirror neurons during the aesthetic experience which can explain the influence of MBAT from neurological point of view: “We propose that a crucial element of esthetic response consists of the activation of embodied mechanisms encompassing the simulation of actions, emotions and corporeal sensation” [40]. They claimed that this process includes empathic responses based on the activity of mirror neurons and embodied simulation. The first stage of gallery art-works reflective contemplation and sharing in the group can enhance communication and self-expression verbally and through art as well. All the above-The use of art making to explore meaning, re-narrating one’s story, increasing resilience through expression and communication of needs, hopes and scars, as well the impact of having a space to come together as creators in a gallery and having a shared aesthetic experience as a group of survivors - inspired the creation of the intervention below. Self-Empathy as well as empathy for others can develop in a “normal” setting which is closer to real life experience.

The intervention: A short-term therapeutic group for survivors of sexual abuse

The first author, an art therapist, and an active artist, participated in an art residency in Afula’s municipal gallery, a relatively small peripheral city in the north of Israel. The exhibition during the time the group took place was titled “Sparkles: Magical Realism in the [Emek Israel] Valley”, included sculpture and paintings by several artists from the Emek Israel area, and the artwork prominently depicted issues connected to the experience of living through the Covid 19 pandemic. Concurrently, the curator of the show connected her with a local social worker from the municipal clinic for the sexually abused. As a result, a short-term therapeutic group was organized in the city’s municipal art gallery following a Covid-19 lockdown. The participants were thus identified as survivors of sexual abuse with formal diagnoses of PTSD. They expressed suffering from increased anxiety and loneliness, and many felt that due to their history and mental health challenges the pandemic exacerbated these symptoms in a more severe way than the general population. Participants also identified that due to the pandemic’s forced isolation of the pre-pandemic community was dismantled, and they experienced loss of social skills acquired prior to the pandemic. Four two-hour meetings were held in the gallery space. The exhibition focused on issues linked to Covid 19 experiences. Viewing the works anchored participants helped them express themselves openly following the aesthetic experience in the gallery.

Each session consisted of three general stages:

a. A tour in the gallery where the participants shared their impressions concerning the exposed art works naturally led to sharing personal issues.

b. An art activity in the gallery studio which is a private space with the conditions for artistic activity.

c. Presentations of participants’ artworks and verbal processing of the aesthetic experience as well as how those connect to personal issues.

In addition, each session consisted of one optional art directive. Directives were offered, but not mandated, and various art materials were available. Participants were invited to follow the instructions; and most did follow the instructions with some modifications according to their own needs. Occasionally they expressed themselves independently. The aesthetic experience enhanced and influenced their expression as well.

a) Create two artworks: One that reflects the difficulties of the Corona period, and the second reflects what helped you to cope with them.

b) Create a safe place.

c) Your wishes for the future.

d) After contemplating all your works, react with a new artwork.

Process Description

The first session began with introductions. Participants and therapists presented themselves. Expectations and worries were discased and the therapists responded and presented the project and set the rules. Each session included a guided tour of the gallery with group discussion concerning the art works. The gallery is big, and the first three sessions were dedicated to different spaces. The last session was dedicated to summarizing through art making and group dialogue. As noted above, the exhibition in the gallery was: “Sparkles-Magical Realism in the Valley” and since it delt with the Artists’ experiences related to Covid -19 closures, stressors of life, and daily realities-the participants deeply related to these topics and responded by expressing their own issues. In addition, the variety of artists and styles included in the exhibition encouraged broad artistic expression. Accordingly, participants showed at least some interest in art, but had various levels of experience, knowledge of interest in art making (Figures 1 & 2). Specifically, during the first two sessions each participant chose an artwork that attracted her the most. and shared her impressions. Others then responded, offering multiple points of view, which deepened their conversation, explorations of the themes, and self-knowing. For example, when relating to the bed sculpture (Figure 3), a participant experienced the bed as a dangerous place, another conceived it as a symbol of depression, and a third saw a shelter in the bed and emphasized the lights as an optimistic symbol. Participants empathically reacted to the different impressions. As an outcome of this exchange, the participants shared complicated personal narratives surprisingly fast with one another and the reactions were supportive and containing. Participants were eager to share their feelings and the artworks were helpful and encouraging, according to their statements.

Toward Systematic Exploration of this Intervention

To systematically assess the intervention, the relevant information is thus organized and analyzed: First, the group process is discussed in the way participants were exposed to it and illustrated through the experience of one participant (Joy) to explicate how artworks exhibited in the gallery as well as group participants’ artworks offer meaningful opportunities for connection and processing. Second, prominent comments made by participants about their experiences are noted. Third, emergent themes are highlighted, and later integrated into a discussion of the value of conducting art-therapy group in a gallery space during a global health crisis. As an illustration of the process participants went through, we will focus on one participant’s reactions, and then explore the overall learning from the group process. So, for example, in a reaction to the hung sculpture (Figure 4), Joy’s (pseudonym) stated, “this is what I want the most, and at the same time, what I fear the most”. It seemed that the sculpture captured her ambivalence-desires and fears - concerning relationships. Joy was the oldest participant and had functioned as a mother figure as one who had a perspective of the possibility of getting better. The bed reminded her of episodes of clinical depression, from which she had periodically suffered throughout her life. She utilized her experience with depression and trauma to encourage the younger participants in the group.

She once regrated her advice to other participant to hospitalize herself when she experienced extreme anxiety Specifically, the youngest participant who was in the beginning of her psychotherapeutic process reported feeling extreme anxiety lately and was consulting the group if it was right to call her therapist. Joy said that she could, and that from her experience, hospitalization can be a good solution. So why did she regret it? and was it processed? Linked to art? When contemplating (Figure 5) Grace, a different participant, said:” It is obvious that the artist had experienced trauma as a child”, which led to deep discussion in the group relating to their childhood. The art therapist artwork (Figure 6) was chosen by Dina, another participant, noticed that although the painter/therapist chose Aquarelle which is very fluid, the borders in the painting are very clear. The therapist/artist was deeply touched and felt exposed by this very profound observation. The group was planned to witness the preparation for the following exhibition that included the therapist/artist solo exhibition. It did not happen because due to Corona restriction and the exhibition took place after the group ended. Here the therapist / artist experienced the coexistence of her two professional identities. Although the therapist / artist felt exposed, a palpable, constructive connection between her two parallel identities was reassuring and new. In a way this direct acquaintance with artist / therapist seemed to have encouraged participants’ authentic expression.

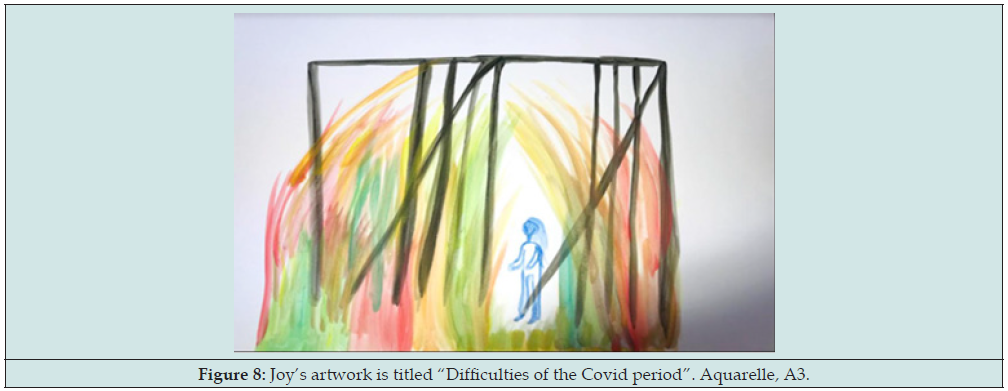

For example, Joy’s artworks speak to this connection. Joy is divorced, mother and grandmother and works part time in helping people fulfil their Israeli social security / health rights with the authorities. During Corona she worked through Zoom and worried that she was not coping now with her fears from the outside world encounters and that she lost the social skill acquired prior to the pandemic. She was eager to get better in this sense because her therapy in the Clinique had a time limit. She created a collage (Figure 7) with photos of nature views, home plants and children (presenting her grandchildren) to symbolize what helped her through the Corona. In her artwork Joy relates to the difficulties of the Covid-19 restrictions (Figure 8). She used different art materials to describe the feeling of loneliness and feeling locked by the colored flame depicted by “shapes and the black bars”, which hold a dominating and invading presence. The composition is heavy on the bottom of the page, while the items on (Figure 5) are scattered on the page without a clear base. According to Joy, these paintings clarified her feelings for herself and communicated them to the group participants.

Figure 7: Joys’ artwork titled “what was helpful in coping with the Corona difficulties”, Magazine images on paper, A3.

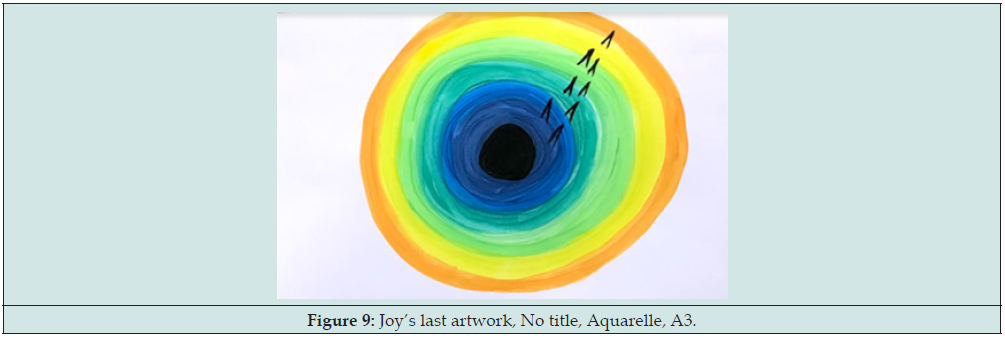

The last session’s directive was for each participant to explore and reflect on all her artworks thus far, paying attention to each work, while also noticing what the artworks have in common. Following contemplation, participants were asked to create a new response art to summarize the process. Joy seemed uncomfortable. She apologized and told the therapists that she could not fulfil this task because her good friend committed suicide the day before. This friend was the one who informed her about the municipal clinic for the sexually abused and was her inspiration as someone who had been rehabilitated. Joy also felt guilty for not contacting her friend for several months. It was clear Joy needed to use the time process this surprising and traumatic loss and could not dedicate herself to the scheduled task. Joy said: “I cannot paint, I see only black”. The art therapist encouraged her to remain with the black and use it as a starting point, validating the necessity to focus on this heartbreaking event. The therapist stayed beside her. She began with black circle (Figure 9). Slowly, she surrounded the black circle with more colors, from cold to warm colors. She consulted the art therapist on how to paint the black birds in a way that would be clear that they are flying upwards. Joy reported that while painting she gradually felt that she had more colors in her life and not only black. The birds became a symbol for her ability to rise from heavy, pulling blackness.

While talking with the group, Joy shared that although she was deeply grieving, painting helped her become aware of the other colors in her life, holding both the grief and the possibilities of life. She also had practical ideas for herself and others in the group coping with heavy grief:, She discussed the importance of reducing isolation and decided to stay with her daughter’s family. She told group members that she never felt like a child during her childhood, but as a grownup she does feel like a child while playing with her grandchildren. Working through her grief by painting and communicating and being supported by the group, Joy could feel there is a way out and that she could overcome what had been experienced as hopeless situation. All in all, it seemed that watching the artworks in the in the gallery and responding to them offered a deep emotional experience that helped participants express themselves openly from the first moment, as illustrated here through Joy’s voyage. Organizing prominent metaphors, processes, and clinical foci

Verbal feedback about participants’ experience the intervention.

This part needs to be deepened / broadened a bit; what is the context for these reflections about the group: Were all group mem bers present? Were their comments recorded systemically? What curiosities / questions about the group or intervention were you trying to answer...? The aesthetic experience and creating art led to deep discussions within the group. Each participant could share her life story and the issues that were bothering us at the present. It happened that one participant reacted without empathy and group dynamics were tense. For example, Joy said that she could not stand staying with the mask for the hole session. She said can sit far from the group, and if it is not agreed, she will understand and leave the group.

The therapists asked the other participants to respond, and a solution was found. Probably, if the group had been for longer term, the group dynamics could be more complicated. At the end of the first session, when asked if they had any requests for the next sessions, they said “more art to see, more art making and more talking”. In the last session they expressed the wish to continue the process. The participants’ individual therapist reported that the themes raised in the group contributed to the individual therapy as well. The experience of the art-therapist and the artist identities in an integrative way was enriching and rewarding for the author.

Emergent themes focused on clinical and creative applications.

As we explored the artwork that emerged throughout this group, reviewed participants verbal response and their unique and shared journeys, several themes emerged:

a. Observations related to the perceived outcomes of the intervention.

b. The differences and similarity of art (viewing) vs. art therapy to propel inter-personal growth.

c. The meaning of holding the intervention during the pandemic. We therefore elaborate a bit on each below and then discuss clinical application and limitations of this study.

1. Perceived outcomes of the intervention

a) According to participants’ consistent attendance, their verbal statements, and comments of clinical staff working with the participants outside of the group, the interventions offered meaningful meetings between group participants and formed a supportive community.

b) Individual and shared experience of deeply witnessing the exhibited artwork, emotional sharing, and creative expression.

c) Forming a unique collaboration between a local galley, a mental health clinic and a graduate art therapy program

d) Establishing need and motivation for continuing and deepening the collaboration

e) Each participant was able to express and reflect on real challenges as well as strengths.

f) The participants had the chance to practice their social skills in a safe space and thus felt a growing ability to cope with social life in the real world.

g) Points for improvement: Participants felt that 2 hours session was too short and felt that four sessions were not enough.

Fine Art and Art Therapy

As we consider the meaning of the use of art therapy techniques within a non-clinical space and one that is typically researched for fine art, a few aspects seem to support the clinical intentions and others require reconsideration / adjusting. Beside the impact of the aesthetic experience with the art machining as enhancing relatively immediately and quickly the participants were eager to express themselves after a long period of isolation (which we will discuss more a bit later) and we believe that bringing together a group of sexual abuse survivors into a public yet protected and intimate space of observation and creation offered healing and comradery. Aspects that enhanced participants experience include

a) Offering the intervention in a non-clinical setting outside of the clinical setting in which the participants normally meet allowed for a different emotional and personal organization.

b) Walking through the gallery and viewing the art exhibited facilitated layered and diverse expression (response art) for group participants.

c) The joint art making, and verbal reflections contributed to a sense of belonging and partnership for participants. Aspects that detracted from clinical intentions that need to be adjusted include A) A clear need for more time-both lengthening the duration of each encounter as well as increasing the number of meetings-to support a sustainable clinical gain. B) A need for consistent and professional supervision for facilitators of the encounters was identified.

This experience summons important considerations for the purpose of art and therapy for women who had been sexually abused, and the unique impact of offering a creative, healing interface in a public, fine art establishment. Specifically, it seems that for women who had been violated, due to the nature of the abuse being sexual-thus visceral, intimate, and one that often carries secrecy and shame for many-viewing art offers an aesthetic experience that echoes their internal experiences and helps create voice and presence for perceptions and sensations that are otherwise wordless. Viewing art together and sharing their understandings and responses with others who share similar challenges-validates and normalizes their experiences. Creating art in response allows for body-mind integration (ref) and when that process occurs as a part of a healing community, there is a palpable sense of mutual witnessing of the unique and shared journeys at play. In this case, choosing to offer this intervention in a prominent, public gallery further sends a message of empowerment for participants: they come to the space as a group of art appreciators, engage in art making, and support one another [15]; all positive roles that are juxtaposed with the inherent identities of victim, patient, or sufferers endemic to surviving such a painful and stigmatized abuse [34].

Group interventions during a global pandemic

The main take away, that is different from meeting physically in a clinic during the pandemic, was the palpable opportunity to reengage and cope with the outside world while they felt they lost the ability to do it dew to the lock downs, isolation and general anxiety connected to the pandemic. The exhibition theme was especially helpful in this sense. The meaning of the specific exhibit, “Sparkles: Magical Realism in the [Emek Israel] Valley” created geographic and cultural belongness / familiarity for participants; all residents of the Emek Israel Valley in Israel. It showcased local artists, whose experiences of surprise, isolation, search for meaning, and anxiety / concern during this unprecedented time in the world resonated with many of the participants. In addition, the role of being an observer, and being the recipient of the aesthetic experience produced by skilled artists, set the stage for deep reflection, metaphoric thinking and curiosity about art materials and processes. These, in turn, inspired the response art of participants as active creators, giving themselves permission to consider their skills, creative challenges and mistakes, and experiment differently than they would in a therapy office.

Discussion

As noted above, the additional value of art-therapy for women who had been sexually abused has been documented before [36]. The innovation here is exploring the impact of serving this population within the setting of a gallery and the impact of doing so at a time of a global crisis. Art therapy in museums and galleries has been experienced before with various populations, for example, the elderly [41]. Art Therapy within non-clinical settings (such as galleries, museums, and community studios) thus offers a unique connection and role for participants. They are a part of a small and purposeful community, which supports the shared and separate reflective journey of each, where they are not merely clients but art viewers and engaged artists. The aesthetic and reflective internal and external space created through the viweing engagement (between each member and each piece of art), the reflective and expressive dialogue inspired by the viewing, further amplifies the impact of the art.

Then, the creation of response art, which normalizes feelings and thoughts, gives voice and images to survivors of sexual abuse as valued members of the community. The fact that the theme of the art exhibition in the gallery was related to the pandemic helped the participants to express their own difficulties. Creating art helped them to be active and productive in relation to experiences in which they were passive and helpless. The group dynamics were meaningful and supportive. They shared their coping skills and experienced deep social interactions in a safe containing environment which encouraged them to practice their social skills in real life. These inter-subjective interactions alleviated their loneliness.

Clinical Applications

When we come to consider tangible takeaways from this intervention, several considerations come to mind. First, finding the right space is crucial. The fact that the gallery offered ample space where participants can engage with the art, and later have an intimate room dedicated to discussing the art and creating art responses- was crucial. The fact that the location was central (well-known and easily accessible) as well as being a recognized gallery in the local art scene-created a draw and amplified the meaning of the intervention as “art-based” [42]. As noted above, the art therapist who facilitated this intervention is well known both as an art therapist and as an exhibiting artist. This fact gave her credence in the eyes of gallery administrators and mental health providers working with the participants, and clearly enabled her to move gracefully and seamlessly between epistemological and experiential frame, curating aspects of fine art as therapeutic and elevating response art through the shared process and aesthetic experience in a gallery space.

Therefore, this experience suggests that the facilitating art therapist’s / artist’s familiarity with both worlds supports the integration of both experiences possible. Defining the community which one offers the intervention, the size of the group and the criteria for inclusion, are always critical for effective clinical work. In this case, however, since the setting formed a non-clinical sub-community of women, it was perhaps even more necessary to have a clear purpose, consistent setting and mental health connections for participants needing additional services. One of the biggest take-aways from this experience centers around the power of the group / community to empower and inspire, and particularly when propelled by a shared aesthetic experience. We hope that reading through participants’ experiences and witnessing some of the artwork they viewed and created in response give readers a sense of the healing potential propelled by integrating art engagements from reflective and expressive, professional, and personal, perspectives.

Limitation of these explorations and suggestions for future research

While the intervention was innovative and both therapist and participants noted how meaningful it was, the group experience and its exploration here is nevertheless anecdotal and thus cannot be replicated or generalized. At the same time, the impact of combining art viewing in galleries or museum with response art and facilitated dialogue in a process received further support for its potential here [43]. Future research might replicate the study with other groups taking place in a gallery or compare these findings to similar interventions offered during a shared health crisis. In addition, future studies might utilize standardized tools to assess the group outcomes and achievement of personal and group goals.

References

- Dissanayake E (2015) What is art for? University of Washington Press, USA.

- Hudson S (2022) Better for the Making: Art, Therapy, Process, a study of the therapeutic basis of process within American visual modernism.

- Cane F (1983) The Artist in Each of US. Art Therapy Publications.

- Dewey J (2005) Art as experience. Penguin.

- Junge MB (2010) The modern history of art therapy in the United States.

- Junge MB (2016) History of art therapy.

- Hogan S (2001) Healing arts: The history of art therapy.

- Allen P (2016) Art making as spiritual path: The open studio process to practice art therapy. In Approaches to art therapy (pp. 271-285).

- Moon C H (2015) Open studio approach to art therapy. The Wiley handbook of art therapy pp. 112-121.

- Finkel D, Bat Or M (2020) The open studio approach to art therapy: A systematic scoping review. Frontiers in psychology 2703.

- Kalmanowitz D, Lloyd B (2004) Inside the portable studio: Art therapy in the former Yugoslavia 1994–2002. In Art therapy and political violence (pp. 126-145).

- Kalmanowitz D (2016) Inhabited studio: Art therapy and mindfulness, resilience, adversity, and refugees. International Journal of Art Therapy 21(2): 75-84.

- Allen P B (2008) Commentary on community-based art studios: Underlying principles. Art Therapy 25(1): 11-12.

- Timm-Bottos J (2011) Endangered threads: Socially committed community art action. Art Therapy 28(2): 57-63.

- Nolan E (2019) Opening art therapy thresholds: Mechanisms that influence change in the community art therapy studio. Art Therapy 36(2):77-85.

- Kapitan L, Litell M, Torres A (2011) Creative art therapy in a community's participatory research and social transformation. Art Therapy 28(2): 64-73.

- Kramer E (1980) Art Therapy and Art Education: Overlapping Functions. Art Education 33(4): 16-17.

- Albert R (2010) Being both: An integrated model of art therapy and alternative art education. Art Therapy 27(2): 90-95.

- Alter-Muri SB (2017) Art education and art therapy strategies for autism spectrum disorder students. Art Education 70(5): 20-25.

- John PAS (1986) Art education, therapeutic art, and art therapy: Some relationships. Art Education 39(1): 14-16.

- Dunn-Snow P, D Amelio G (2000) How art teachers can enhance artmaking as a therapeutic experience art therapy and art education. Art education 53(3): 46-54.

- Reyhani Dejkameh M, Shipps R (2018) From please touch to Art Access: The expansion of a museum-based art therapy program. Art Therapy 35(4) 211-217.

- Hartman A (2021) Exploring Museum-based Art Therapy: A Summary of Existing Programs. In Museum-based Art Therapy (pp. 16-41).

- Salom A (2015) Weaving potential space and acculturation: Art therapy at the museum. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 6(1): 47-62.

- Salom A (2011) Reinventing the setting: Art therapy in museums. The Arts in Psychotherapy 38(2): 81-85.

- Hamil S (2016) The art museum as a therapeutic space (Doctoral dissertation, Lesley University).

- Linesch D (2004) Art therapy at the museum of tolerance: Responses to the life and work of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. The Arts in Psychotherapy 31(2): 57–66.

- Deane K, Carman M, Fitch M (2000) The cancer journey: bridging art therapy and museum education. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal 10(4): 140-142.

- Thaler L, Drapeau CE, Leclerc J, Lajeunesse M, Cottier D et al. (2017) An adjunctive, museum-based art therapy experience in the treatment of women with severe eating disorders. The Arts in Psychotherapy 56: 1-6.

- Aguilar S (2019) Art Therapy in a Museum Setting for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A. Art Therapy.

- Waller C S (1992) Art therapy with adult female incest survivors. Art Therapy 9(3): 135-138.

- Pifalo T (2009) Mapping the maze: An art therapy intervention following disclosure of sexual abuse. Art Therapy 26(1): 12-18.

- Kometiani MK, Farmer KW (2020) Exploring resilience through case studies of art therapy with sex trafficking survivors and their advocates. The Arts in Psychotherapy 67: 101582.

- Goodarzi G, Sadeghi K, Foroughi A (2020) The effectiveness of combining mindfulness and artmaking on depression, anxiety, and shame in sexual assault victims: A pilot study. The Arts in Psychotherapy 71: 101705.

- Backos AK, Pagon BE (1999) Finding a voice: Art therapy with female adolescent sexual abuse survivors. Art Therapy 16(3): 126-132.

- Markman Zinemanas D (2014) Visual symbol formation and its implications for art psychotherapy with incest survivors-A case study. ATOL Art Therapy Online 5(2).

- Braus M, Morton B (2020) Art therapy in the time of COVID-19. Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy 12(S1): S267.

- Potash JS, Kalmanowitz D, Fung I, Anand SA, Miller G M (2020) Art therapy in pandemics: Lessons for COVID-19. Art Therapy 37(2): 105-107.

- Miller G, McDonald A (2020) Online art therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. International journal of art therapy 25(4): 159-160.

- Freedberg D, Gallese V (2007) Motion, Emotion and Empathy in Esthetic Experience, Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11(5): 197-203.

- Bennington R, Backos A, Harrison J, Etherington Reader A, Carolan R (2016) Art therapy in art museum: Promoting social connectedness and psychological well-being of older adults, The Arts in Psychotherapy 49: 34-43.

- Allen PB (2008) Commentary on community-based art studios: Underlying principles. Art Therapy 25(1): 11-12.

- Krauss L, Ott C, Opwis K, Meyer A, Gaab J (2021) Impact of Contextualizing Information on Aesthetic Experience and Psychophysiological Responses to Art in a Museum: A Naturalistic Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication 15(3): 505-516.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...