Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4722)

Viral Infections in Infants with Neonatal Hepatitis Volume 3 - Issue 1

Maryam Monajemzadeh1*, Amin Rezvani2, Mohammad Vasei3, Parin Tanzifi4, Reza Khorvash5, Farzaneh Motamed6 and Maryam Eghbali7

- 1Associate professor in clinical and surgical pathology, Department of Pathology, Children Medical Center Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Keshavarz Boulevard, Tehran, Iran

- 2Clinical and surgical pathologist, Department of Pathology, Children Medical Center Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Keshavarz Boulevard, Tehran, Iran

- 3Professor in clinical and surgical pathology, Department of Pathology, Children Medical Center Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Keshavarz Boulevard, Tehran, Iran

- 4Assistant professor in clinical and surgical pathology, Department of Pathology, Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Keshavarz Boulevard, Tehran, Iran

- 5Faculty of Science, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

- 6Professor in pediatrics gastroenterology, Department of pediatrics gastroenterology, Children Medical Center Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Keshavarz Boulevard, Tehran, Iran

- 7Department of Pathology, Children Medical Center Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Keshavarz Boulevard, Tehran, Iran

Received: December 09, 2020 Published: December 23, 2020

Corresponding author: Maryam Monajemzadeh, Pathology department, children medical center Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Keshavarz Boulevard, Tehran, Iran

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2020.03.000154

Abstract

Introduction: Neonatal cholestasis is a common manifestation of various pathologies. These pathologies include direct hepatocellular injury, defects in hepatocyte bile formation, or mechanical obstruction of bile flow. Histologically, most of the biliary tract diseases, infections, genetic and metabolic diseases can display parenchymal inflammation leading to the diagnosis of Neonatal Hepatitis (NH). Hence, NH implies a pattern of neonatal liver disease rather than a specific cause of liver injury. Among non-obstructive causes, various viral infections are associated with NH. The unmasking of the etiology of NH in further patients’ management is extremely important. Also, the prevalence of viral associated NH varies among different studies. Therefore, we planned to investigate the frequency of common viral agents in infants diagnosed with Idiopathic NH (INH).

Objective: A total of 138 consecutive infants with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia undergoing liver biopsy were collected as well as thirty-one umbilical cord tissues belonging to normal infants as controls. Patients with known etiology of NH were excluded from the study, and 74 cases diagnosed with INH were enrolled. Nucleic acid from the liver tissues of patients was extracted and real-time PCR for the detection of EBV, CMV, HSV1, HSV2, and HHV6 was done.

Results: The mean age of the patients at the time of liver biopsy was 70 days (minimum: 22, maximum: 98 days). There were 36 males and 38 females. CMV DNA was detected in six patients and HHV6 DNA was detected in one patient, while all control tissues were negative for the viral DNAs (p<0.05). None of the other tested DNA viruses could be detected in liver tissues. In addition, none of the liver samples were positive for CMV inclusions in hepatocytes or biliary epithelium under the light microscope.

Conclusion: In conclusion, we found CMV DNA in six liver biopsies without any histological evidence of CMV infection. Using more sensitive methods such as PCR is warranted to determine viral DNAs in the liver tissues and establish their role in the development of NH. Further studies with larger populations should be conducted to provide more information regarding the role of viruses in the development of NH and compare their frequency in different populations.

Keywords: Neonatal Hepatitis; Cytomegalovirus; Cholestasis; PCR

Introduction

Neonatal conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is a common manifestation of mechanical obstruction of bile flow, direct hepatocellular injury and also defects in hepatocyte bile formation [1]. The distinction between biliary tract obstruction and hepatocellular injury is critical for clinical management of Neonatal cholestasis. Thus, the primary goal in patients’ management is to differentiate obstructive and nonobstructive causes of hyperbilirubinemia [2]. Once the obstructive causes are excluded, the next step would be evaluating the nonobstructive etiologies of hepatocellular injury. Due to the immaturity of the biliary system and hepatocytes, different injuries result in similar clinical presentations with a significant overlap of laboratory and pathological findings [3]. Indeed, most of the biliary tract diseases, infections, genetic and metabolic diseases can display parenchymal inflammation leading to the diagnosis of Neonatal Hepatitis (NH) by pathologists. Therefore, NH means a pattern of neonatal liver disease instead of a specific cause of liver injury. Advances in the understanding of neonatal liver diseases as well as the implication of new testing modalities allow for the unmasking of the etiology in most cases. The most common etiologies include infectious and metabolic diseases [4]. Metabolic causes can be suggested based on histological and clinical clues and can be confirmed using biochemical, molecular and genetic tests. However, despite all investigations, no etiology has been found in approximately 30% of infants with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and this group of patients is addressed as Idiopathic Neonatal Hepatitis (INH) [3].

Many viruses, including Enterovirus, Adenovirus, hepatitis A‐E viruses, Coxsackievirus, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Herpes simplex virus, Epstein Barr virus, Influenza virus and Human Herpesvirus 6 are associated with NH [5,6]. The virus may be transmitted from mother to fetus or acquired after birth [7]. While most of the infants with congenital infection show no evidence of disease at birth, approximately 5% of infants have neurological, respiratory, hematopoietic and gastrointestinal involvement by virus leading to long-term sequels [5]. The prevalence of infection leading to NH varies in different age groups and increases with age, also depending on socioeconomic status and the viral detection method. Congenital CMV infection is observed in about 0.2 to 2.4% of all live births [5] with seroprevalence of 60-90% in Central Europe [8, 9] and the USA [8, 10, 11]. In a study by Funato [12] CMV DNA was detected in 58.1% of infants with NH [12]. Another study on Korean children showed evidence of CMV infection in 31% of the kids with acute non-A, B, C viral hepatitis [13]. Continuous states or latent infection is characteristic of infection by most of these viruses [6]. Therefore, positive serological tests are not sufficient to confirm an association of viral infection with hepatitis. Additionally, the overlapping histological and clinical features in infectious associated NH and INH result in difficulty in distinguishing etiologies in most cases. The etiology of NH in further patients’ management is extremely important and the prevalence of viral associated NH varies among different studies. CMV isolation in liver tissues in patients with INH has been rarely reported, and little information exists in the literature in this regard [14-18]. Therefore, we planned to investigate the frequency of common viral agents, including CMV, EBV, HHV6, HSV1 and 2, in infants diagnosed with INH using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

Methods

The study was conducted in the pathology department of Children Medical Center Hospital, affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences. From April 2009 to July 2016, a total of 138 consecutive infants with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia undergoing liver biopsy were collected. Thirty-one umbilical cord tissues belonging to normal infants with no illness in their sixmonth follow up were included in the study as controls. Neonatal cholestasis was defined as jaundice within the first 4 months of age with conjugated bilirubin of more than 20% of the total serum bilirubin. The Biliary atresia was diagnosed according to Fischler et al criteria [18,19]. Patients with biliary tract obstruction, family history of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, alpha one antitrypsin deficiency, known metabolic causes such as tyrosinemia, sepsis and those with insufficient tissues were excluded from the study, leading to a final number of 74 cases diagnosed with INH. No other defined etiologies were found in the formation of cholestasis in these patients, all were full-term infants with normal birth weights with unremarkable perinatal histories. The diagnosis of INH was based on clinical findings, laboratory evaluations, biochemical data, imaging tests and liver biopsy. Age, gender and clinical manifestations were extracted from the archive. Serum aminotransferases (AST and ALT), Gamma Glutamyl Transpeptidase (GGT), total and direct bilirubin levels, serum-concentration of alpha one antitrypsin, sweat chloride test results, HIDA scan of the gallbladder and biliary system, abdominal ultrasound, TORCH study, intraoperative cholangiography, associated anomalies, serum amino acid chromatography and any other factor with possible etiologic importance were retrieved from medical records when available. Ongoing CMV infection was defined by the detection of serum CMV IgM or evidence of the presence of CMV in the urine [8-11, 20]. Hematoxylin and eosin, PAS, trichrome and reticulinstained slides were reviewed for all 74 cases with special attention to the presence of viral cytopathic effect and proper paraffin blocks were selected for nucleic acid extraction and PCR study.

Nucleic Acid Purification

Using disposable blades, two 5μm sections of paraffin blocks were made and transferred to DNAse/RNAse free tubes followed by deparaffinization. Nucleic acids were extracted using Roche High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) as instructed by the manufacturer. Briefly, deparaffinized tissue was incubated with tissue lysis buffer and proteinase K at 55◦C until tissue particles disappeared completely. Then binding buffer and isopropanol were added. The DNA was eluted into a final volume of 200 μL, quantified photometrically using nanodrop, Thermoscientific 1000, USA and stored in −70◦C. Each sample was subject to Real-time PCR for the detection of EBV, CMV, HSV1 and 2 and HHV6 (AmpliSens PCR kits, Bratislava, Slovak republic) on rotor gene 6000 (Corbett Research, Mortlake, Australia). Negative, positive and internal controls were run in each performed PCR assays. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tehran University of medical sciences and was in agreement with the Helsinki Declaration. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 16.0.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To report the frequencies and differences between groups, descriptive statistics and Student’s t-test were employed respectively in which P-values of less than 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

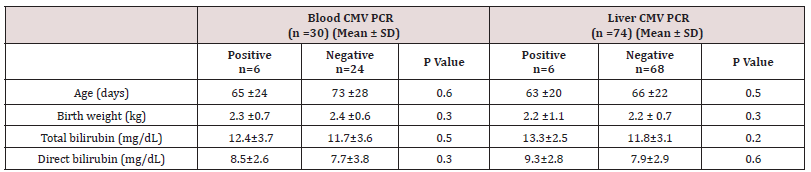

A total of 138 consecutive infants with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia undergoing liver biopsy with a final diagnosis of NH were studied. Cases with biliary tract obstruction, family history of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, alpha one antitrypsin deficiency, known metabolic causes such as tyrosinemia, sepsis and those with insufficient tissues were excluded from the stud, leading to a final number of 74 cases. The mean age of the patients at the time of liver biopsy was 70 days (minimum: 22, maximum: 98 days). There were 36 males and 38 females. The clinical data was gathered with the most common clinical presentation being jaundice and the onset of jaundice was on 24.2 ±17 days of life. The mean birth weight was 2.4 ±0.7 kg. IgM and IgG serology for CMV were available for 52 patients and 30 patients out of these 52 patients also had blood CMV PCR results in their charts. No data regarding CMV serology or blood CMV PCR was found for the rest of patients. CMV IgM and IgG were positive in 8 and 11 patients (out of 52 patients), respectively and PCR for blood CMV DNA was positive in 6 patients (out of 30 patients). Using PCR, CMV DNA was detected in six and HHV6 DNA in one patient while all control tissues were negative for the viral DNAs (p<0.05). None of the other tested DNA viruses could be detected in liver tissues. Among patients with positive CMV serology, three infants showed CMV DNA in the liver. These three patients also were positive for blood CMV DNA. For one case with positive liver CMV DNA no data was available regarding serology or blood CMV PCR. The other two cases with positive liver CMV DNA showed only positive viral serology (both high IgM and IgG), but negative blood CMV DNA PCR results.

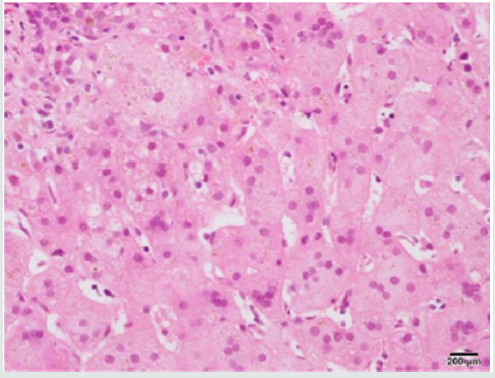

None of the liver samples were positive for cytomegalovirus inclusions in hepatocytes or biliary epithelium (Figure 1). The mean level of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels was 187 IU/L (12-572 IU/L), while serum alanine aminotransferase (AST) counterpart was 308 IU/L (29-1592 IU/L). The mean level of AST and ALT, GGT, total and direct bilirubin levels and serumconcentration of alpha one antitrypsin did not differ between cases with positive and negative DNAs (p>0.05). Table 1 shows the clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients enrolled in the study.

Figure 1: Liver biopsy shows neonatal hepatitis as giant cell transformation of hepatocytes in a patient with positive CMV serology and PCR (H&E).

Discussion

INH is an important cause of neonatal cholestasis. Classically, infants with INH reveal normal biliary trees and elevated levels of conjugated bilirubin. The clinical picture is not unique and often there is an overlap with other causes of neonatal cholestasis. As the treatment protocols for each category of diseases differ, extensive radiological, histological, biochemical, microbiological and even molecular workup is an essential part of the diagnostic algorithm. Histologically, hepatic giant cells, inflammation and lobular cholestasis are evident while there are no clues to obstructive changes of biliary atresia, the paucity of intrahepatic bile ducts, viral inclusion or abnormally stored materials inside the hepatocytes. However, in the first few months of life, we cannot rely on histology or serology alone to rule out storage disease or infectious processes as the false-negative rate is high. As the infectious process is one of the leading causes of NH which can be missed on routine histological or serological studies, we retrospectively did PCR on liver tissues of infants diagnosed with INH to understand the frequency of few common viral infections as possible etiology and their clinical and histological correlates [1]. We found CMV DNA by real-time PCR system in the liver tissues of six patients with NH, which was not observed in the control group. CMV infection is one of the main causes of NH among other viruses [6, 9, 12, 21]. Direct evidence of the role of viruses in the disease process is difficult to be established; however, the detection of the virus from the liver tissue is regarded as evidence of the role of CMV in NH [6,12 9,21]. We identified IgM anti-CMV antibodies and markedly elevated titers of IgG anti- CMV antibodies in three out of six cases with positive liver CMV PCR and so CMV was the most likely cause of neonatal hepatitis in these infants. Primary CMV infection can be detected by the presence of serum anti-CMV IgM antibody or the seroconversion of the IgG antibody. However, in infants, the antibody production is limited due to the immaturity of the immune system resulting in negative results for anti-CMV IgM antibodies. In addition, the passive acquisition of antibodies from the mother may complicate the serodiagnosis of CMV infection. We reviewed all the biopsies again with special attention to the viral cytopathic effect in these six infants, but no viral cytopathic effect was observed. The absence of CMV inclusion may be related to its rarity in the biopsies of immunocompetent patients [6].

5 infants in this study were positive in terms of anti-CMV IgM but negative with respect to CMV DNA. This may be due to false-positive results, the passage of antibodies from mothers, or low sensitivity of our PCR assay in the presence of low levels of CMV DNA. Indeed, serology has a low specificity for the diagnosis of CMV hepatitis and cannot differentiate between active and latent infections. Few reports have been published describing the frequency of the association of CMV infection with NH. The prevalence of the finding of CMV in our stud is lower than in Funato et al. and Shibata et al, both with the rate of infection of 23–67% of infants [6, 12]. Here, we should mention that by different PCR techniques, the rate of viral DNA isolation varies. Different study populations are other important factors. It also implies the negative test results for other DNA viruses in the present study. HHV-6 DNA was detected in one 60-day girl with mildly increased levels of ALT and AST. Although this virus shows replication mainly in lymphocytes, in the Pischke study it has also been amplified from liver tissue especially in patients with graft hepatitis [8]. Our study has some limitations. First, although we found CMV DNA in six patients with hepatitis, its responsibility for the development of hepatitis cannot be confirmed by our method. By the way, direct detection of CMV DNA in liver tissue can support its direct role in hepatitis development. Second, we cannot conclude that the negative PCR result is because of the absence of viruses as the amount of viral DNA may be lower than the test threshold. Third, blood CMV PCR and CMV serology results were not present in all patients so we could not determine the sensitivity of the tests. In summary, we found CMV DNA in six liver biopsies without any histological evidence of CMV infection. Using more sensitive methods such as PCR is warranted to find out CMV or other viral DNAs in the liver tissues in the absence of viral cytopathic effects and establish their role in the development of NH. Antiviral therapy may help NH recovery and reduce potential complications of infections. Further studies with larger populations should be carried out to provide more information regarding the role of viruses in the development of NH and compare their frequency in different populations.

References

- Torbenson M, Hart J, Westerhoff M (2010) Am J Surg Pathol. 34(10):1498-503.

- Bellomo Brandão MA, Porta G, Hessel G (2008) Clinical and laboratory evaluation of 101 patients with intrahepatic neonatal cholestasis. Arq Gastroenterol 45(2): 152-155.

- Quaglia A, Roberts EA, Torbenson, M (2018) Developmental and Inherited Liver Disease. In: Burt AD, Ferrell LD, Hübscher Stefan G, MacSween's Pathology of the Liver. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier: pp. 111-274.

- Ruchelli E, Rand EB, Haber BA (2016) Hepatitis and liver failure in infancy and childhood. In: Russo P, Ruchelli E, Piccoli DA, editors. Pathology of Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Springer-Verlag Berlin (An): pp. 255–258.

- Na SY (2012) Cytomegalovirus Infection in Infantile Hepatitis. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 15(2): 91-99.

- Kangro HO, Osman HK, Lau YL (1994) Seroprevalence of antibodies to human herpesviruses in England and Hong Kong. J Med Virol 43: 91–96.

- Bellomo Brandao MA, Andrade PD, Costa SC (2009) Cytomegalovirus frequency in neonatal intrahepatic cholestasis determined by serology, histology, immunohistochemistry and PCR. World J Gastroenterol 15(27): 3411-3416.

- Pischke S, Gösling J, Engelmann I (2012) High intrahepatic HHV-6 virus loads but neither CMV nor EBV are associated with decreased graft survival after diagnosis of graft hepatitis. J Hepatol 56(5): 1063-1069.

- Chang MH, Huang HH, Huang ES (1992) Polymerase chain reaction to detect human cytomegalovirus in livers of infants with neonatal hepatitis. Gastroenterology103(3): 1022-1025.

- Staras SA, Dollard SC, Radford KW (2006) Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988– 1994. Clin Infect Dis 43: 1143–1151.

- Krueger GR, Koch B, Leyssens N (1998) Comparison of seroprevalences of human herpesvirus-6 and -7 in healthy blood donors from nine countries. Vox Sang 75: 193–197.

- Funato T, Satou N, Abukawa D (2001) Quantitative evaluation of cytomegalovirus DNA in infantile hepatitis. J Viral Hepatol 8: 217-22.

- Son SK, Park JH (2005) Clinical features of non-A, B, C viral hepatitis in children. Korean J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 8: 41-48.

- Hasosah MY, Kutbi SY, Al-Amri AW (2012) Perinatal cytomegalovirus hepatitis in Saudi infants: a case series. Saudi J Gastroenterol 18: 208–213.

- Shah I, Bhatnagar S, Dhabe H (2012) Clinical and biochemical factors associated with biliary atresia. Trop Gastroenterol 33: 214–217.

- Fischler B, Woxenius S, Nemeth A (2005) Immunoglobulin deposits in liver tissue from infants with biliary atresia and the correlation to cytomegalovirus infection. J Pediatr Surg 40: 541–546.

- Goel A, Chaudhari S, Sutar J (2018) Detection of Cytomegalovirus in Liver Tissue by Polymerase Chain Reaction in infants with neonatal cholestasis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 37(7): 632‐636.

- Fischler B, Papadogiannakis N, Nemeth A (2001) Aetiological factors in neonatal cholestasis. Acta Paediatr. 90: 88-92.

- Fawaz R, Baumann U, Ekong U (2017) Guideline for the Evaluation of Cholestatic Jaundice in Infants: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 64(1): 154‐168.

- Danks DM, Campbell PE, Jack I (1977) Studies of the etiology of neonatal hepatitis and biliary atresia. Arch Dis Child 52: 360-367.

- Tajiri H, Kozaiwa K, Tanaka Taya K (2001) Cytomegalovirus hepatitis confirmed by in situ hybridization in 3 immunocompetent infants. Scand J Infect Dis 33(10): 790-793.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...