Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Research article(ISSN: 2637-4722)

Various Perspectives on Illness in School - a Pilot Study Volume 4 - Issue 5

Nicola Sommer*

- *University of Teacher Education, Institute for Educational Sciences, 5020 Salzburg, Akademiestraße 23-25, Austria

Received: January 25, 2024 Published: January 30, 2024

Corresponding author: Nicola Sommer, University of Teacher Education, Institute for Educational Sciences, 5020 Salzburg, Akademiestraße 23-25, Austria

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2024.04.000197

Abstract

Background

Teachers face increasing challenges due to their students’ illnesses, attributed to better medical outcomes or surge in lifestyle diseases. On average, each class has four students with illnesses. Implementing therapeutic measures in schools is crucial due to students’ extended time there. Caring for children with chronic illnesses depends on structural, organizational, and pedagogical factors. Overcoming challenges ensures full inclusion, which is vital as chronic diseases affect students’ performance and mental health. Support for teachers through training and effective communication is crucial, as it can mitigate the impact of illnesses. This study aims to identify challenging areas in managing chronic diseases at school and derive practical suggestions.

Methods

The study comprised 31 expert interviews in Austria. Participants shared experiences related to chronic illness and its impact on school life. Five categories were identified through a thematic qualitative content analysis: impact on daily life, challenges in school, paths to promote inclusion, opportunities to meet academic requirements, and communication, linked to the statements from the interviews. The statements related to the categories were additionally quantified to facilitate a comprehensive understanding. Aspects with high and low variability were emphasized.

Results

Challenges faced by ill children are seldom perceived by teachers, but parents and children clearly feel them. Regarding challenges in school or fears related to dealing with the illness, both parents and teachers emphasize the importance of it, children only partly perceive them. Parents rarely perceive teachers’ support measures and the well-being of their children. Teachers observe the impact of the illness on performance, and both teachers and parents mention the need for regular communication.

Conclusion

The perspectives of students with illnesses, their parents, and teachers differ in many aspects. Only through effective communication can different perceptions be addressed, and changes initiated. Affected students should be actively involved in the dialogue.

Keywords: Pedagogy; school; chronic diseases; children; different perspectives

Introduction

Teachers are increasingly confronted with their students’ illnesses, because of better medical treatment successes, and/or due to an increase in civilization diseases or the effects of various stresses [1]. Currently, there are an average of four children and adolescents with a chronic disease in each class [2]. Students spend a lot of time at school every day. Therefore, it is essential to incorporate necessary measures of therapy and restrictions due to different disease patterns [3]. Many structural, organizational, and pedagogical barriers must be overcome to ensure full inclusion for affected students [4]. Chronic diseases pose several challenges for affected individuals, including pain, care management, medicaltherapeutical measures, and financial and psychosocial losses. These challenges can cause concern about the future and mental health problems. For parents of children with chronic diseases, caregiving and problem solving can also be a significant challenge [5-7]. Additionally, administering medication and first aid in school can be difficult, and chronic diseases can negatively impact school experiences and performance [8-9].

Creating a successful, inclusive, and educationally supportive environment for students requires a range of organizational and structural arrangements [10]. This can include implementing policies and procedures, as well as ensuring that the physical environment is accessible [11]. Another key aspect is the education and training of teachers, which should focus on developing an understanding of the needs of students with diverse backgrounds and abilities [12]. Institutional and interdisciplinary communication and cooperation are also important for creating an inclusive environment [13]. This involves ensuring that all members of the school community work together effectively, including administrators, teachers, parents, and other caregivers [14]. In terms of preventative measures, schools should prioritize student well-being and provide early intervention support for those who may be struggling. This can include a range of psychosocial support services, as well as resources for parents, teachers, and caregivers [15].

An important part amongst others is to raise awareness for teachers and classmates regarding the effects of illnesses, in a way that is agreed upon by the ill student and the family. This allows teachers to better support students with diseases in different situations like medical emergencies or similar [16]. If a strong relationship between teachers, parents, and students with and without diseases can be established - and if concerns of all the involved parties are treated seriously - diseases can become secondary [17].

The aim of this study is to identify challenging areas in dealing with chronic diseases in school and to highlight the areas where affected students, teachers, and parents have different perspectives. Practical suggestions are intended to be derived from it.

Methods

The study was based on 33 guideline-based expert interviews conducted in Austria from July 2019 to March 2020. Participants included eight children, 12 parents, and 11 teachers. Anonymity was prioritized during recruitment, involving individuals with various medical conditions throughout Austria. Recruitment occurred through direct contact and word-of-mouth. The material has already been analyzed using Grounded Theory [18]. Triangulation of methods allows for different perspectives on the material. Therefore, the data material was used again here to shed light on the research question from an additional perspective [19]. Participation was voluntary, and interviews occurred in hospitals, participants’ homes, or online via Zoom. All participants agreed to recording and transcription. To ensure intercoder reliability, the first three interviews were conducted as pre-tests. Insights from these pre-tests led to the decision to remove the questions regarding performance, motivation, and behavior from the teacher questionnaire and simplify the questions about absences or the school action guide. All other questions and questionnaires remained unchanged.

The interview durations ranged from 5 to 60 minutes and were transcribed using the simplified system by Dresing and Pehl [20]. Participants were encouraged to share their experiences related to chronic illness and its impact on school life. The analysis will draw upon Mayring’s content analytical communication model [21], aiming to uncover statements about the emotional, cognitive, and action background of the participants. Interview topics included knowledge about chronic diseases, the daily burden of illness, coping at school, absenteeism, inclusion, and academic performance. Thematic qualitative summarizing content analysis was employed and categorized into five themes: impact on daily life, challenges in school, paths to promote inclusion, opportunities to meet academic requirements, and communication. The findings were quantified for a comprehensive understanding, highlighting aspects with high and low variability, and linking them to interview statements.

Results

Category 1: Impact on daily life

The children in the study are aware that their diseases will last a lifetime. They highlight the necessity of therapeutic measures throughout the day and night, acknowledging that their parents handle this responsibility and expressing acceptance of it. They mention various effects of their illness and side effects of therapeutic measures (increased risk of infection, pain, difficulty falling asleep, limitations in sports, environment-dependent symptoms or avoidance of specific places). Adjustments to therapeutic measures are frequently necessary and their effective implementation reduces the time required.

And then my mom usually prepares a pot for me in case I have to vomit because it happens from time to time, as I feel nauseous... and then it’s like I feel sick for the rest of the day and usually the next day too (I11_S_04).

Parents mention that an illness disrupts the entire daily routine, but they can generally cope well with it. They bear significant responsibility and strive to provide everything for their children. Organizing a normal daily routine requires considerable time. Therapeutic measures must be carried out day and night, leading to uncertainty due to the illness. Parents observe the effects of therapeutic measures on their children (concentration, performance, physical appearance or sports) and experience considerable stress themselves (supervision during leisure activities, frequent hospital stays, therapeutic measures day and night, hygiene measures, precise schedules, diets, approval procedures for therapies or unpredictable events). The time until diagnosis is described as challenging and the illness is often suppressed, but activities like rehab stays or rituals are supportive. Siblings are also a valuable resource.

One year was good, and then it just came back, where the low blow hit again. I don’t want this! (I11_E_08).

Teachers note that certain effects of the illness are only observable at home, leading to burdens on parents and siblings. If family care and suitable medications are available, it alleviates the burden. However, if siblings are also affected by the same illness or if it is life-threatening and additional care and therapy are lacking, the burden on parents is very high.

We are all very concerned that he will live for a long time, namely LIVE well, that he is doing well (I04_L_17).

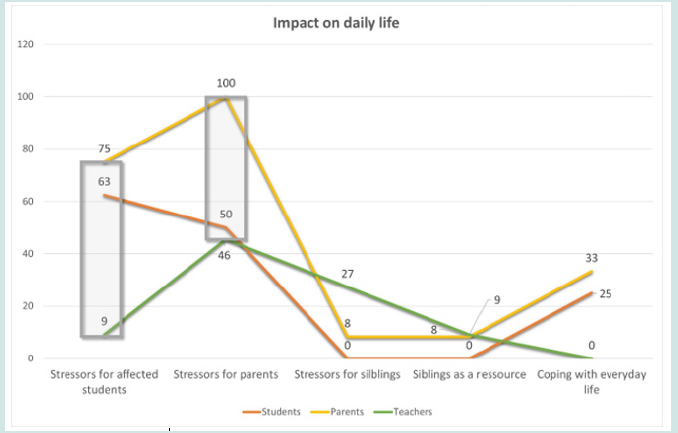

Regarding the frequency of statements, there is the greatest variability in the categories of stressors for affected students and stressors for parents. Only 9% of teachers mentioned stressors for affected students, whereas stressors for parents were mentioned by 46% of the respondents. However, both students and parents frequently highlighted their own stressors due to the illness (figure 1).

Category 2: Challenges in school

Affected children mention that they are enthusiastic about school, but the illness and therapeutic measures have various consequences on their education (exemptions from sports, no field trips, absences). Additionally, therapeutic measures are often necessary throughout the entire day, and they also have physical effects, including pain. They wish for teachers to support therapeutic measures, be aware of emergency measures, and consider the illness (making up missed material, choosing excursion destinations, responding to behavioral changes or academic decline, preventing overload).

But it depends. And it’s also like that, usually the next day, if I’ve injected now, usually in the evening, the next day I feel so, my whole body is so weak, and I somehow have a stomachache, and it just feels like I have to vomit, which I haven’t done, it’s like everything is weak and everything, and the right side of the chest hurts (I11_S_4).

Parents emphasize that their children enjoy going to school. In the case of severe illnesses, school is seen as a meaningful activity, but academic performance is not a priority in such situations. Homeschooling or hospital education can be alternatives in these cases. Some illnesses are not visible, while therapeutic measures lead to physical, cognitive, and psychological changes in children (scars, hair loss, effects on short-term memory, etc.). Adjustments are often necessary (shortening school hours, accepting delays, exemption from physical education, choosing excursion destinations, organizing events, hygiene, special sessions). Parents wish for teachers to observe and notice changes in the affected children, responding promptly (reporting to parents, adjusting the curriculum), as children often overburden themselves or suppress the illness. Parents desire awareness of the illness’s impact, seeking consideration and support for therapeutic measures. The independence of children in carrying out therapeutic measures is encouraged. Teachers should be prepared for emergency measures to reduce their own fear. A guideline for teachers could be a possible approach, but parents also understand hesitancy. Concerns arise, particularly during outings, in physical education or unplanned activities (overburdening). Parents’ burdens include acting as companions, needing to request support, or facing refusals of assistance and adjustments.

Something special, you can notice, currently, only that her hair has fallen out, and she has a big cut over more than half on her head, otherwise she is completely different, she has never had any disability or what I know (I06_E_18).

Teachers generally expect the same performance from ill children as from all other students. In some cases, illnesses are not even noticed, partly because students independently carry out their therapeutic measures. However, certain illnesses have noticeable effects (therapeutic measures during class, eating restrictions, changes, pain), requiring adjustments (fewer assignments, leaving school earlier, strategies for remembering therapeutic measures, classroom adaptations, clear structure). Guidelines would be helpful for teachers in such situations. Teachers also express empathy for the ill child and acknowledge the burdens on the parents. Additional support from assistants or therapists, when available, helps alleviate the burden on teachers.

The difficult thing is that you always feel responsible (I10_L_25).

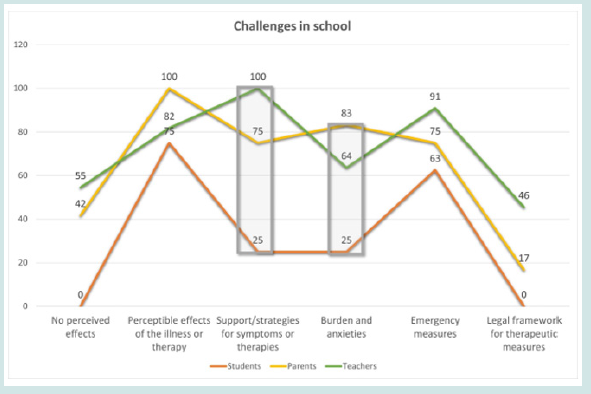

Challenges in school, especially in Support or strategies for symptoms and therapy and Burden and anxiety, show notable differences. Only 25% of students expressed the need for school support, while 75% of parents and all teachers emphasized its importance. Similar patterns were observed for Burdens and anxieties, mentioned by 25% of students but 83% of parents and 64% of teachers (figure 2).

Category 3: Ways to promote inclusion

Students enjoy being in school, meeting friends, participating in sports, and going on outings. After absences, they wish to be warmly welcomed back by their classmates. Occasionally, they notice limitations due to the illness, but these are manageable. Children desire consideration during celebrations and outings, as well as teachers inquiring about their well-being. School should be enjoyable.

That they just accept it, so it’s not my fault that I have the disease (I09_S_46).

Parents wish for their child not to have an exceptional status in school but to be treated as normally as possible. They fear bullying and exclusion, desiring ongoing contact during absences. The impacts of the illness are at times not taken seriously by peers and teachers, leading the child to engage in sports despite pain to avoid exclusion. However, there is generally an awareness of restrictions in sports, celebrations, events, or school outings to prevent disappointment and exclusion for the affected child. To facilitate inclusion, classmates should be informed about the illness, with the child deciding how this is done. Parents express concerns about not having peace of mind during outings or having to act as accompanying persons themselves. Additional support would simplify the child’s school attendance.

She was completely normal, and she received a letter, so I was very pleased, the teacher had each child write or draw a letter, and she received a whole bunch while in rehab, IT WAS SO NICE. SHE WAS REALLY HAPPY. So, essentially, we’re thinking of you, and we look forward to your return. That really fit well (I12_E_30).

In the class, open discussions about the illness are encouraged. School friends should be informed about the illness and emergency measures should be discussed. For teachers, it is important to accept that each child is different and to accommodate exceptions (such as dietary needs, therapeutic measures, breaks). Children should show understanding, which can be achieved through discussions addressing any inequalities within the class. In case of absences, maintaining contact is crucial, and upon the child’s return, things can resume normally. Planning for events and school outings should be discussed early with parents to facilitate participation. Assistants, supportive colleagues, and team teaching make it easier to address the needs of children with illnesses. School friends play a significant supportive role.

So, simply not losing contact, but always making sure that it always feels right when they return to school, and that everything is fine, and no one is disappointed or finds it strange, but is simply taken back normally (I10_LP_28).

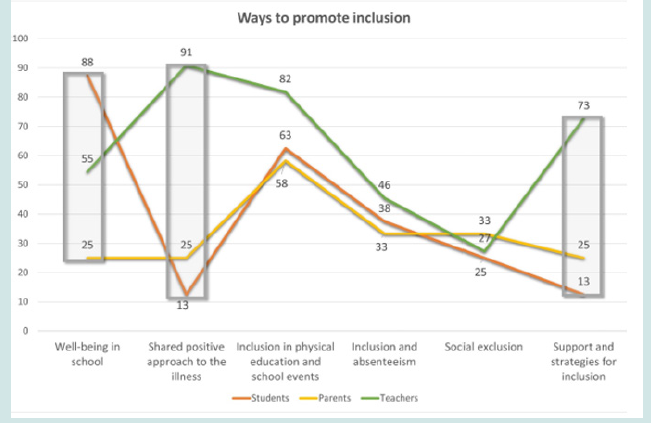

Regarding inclusion in school, 91% of teachers believe that everyone is managing well with the illness. However, students and parents do not pick up on teachers’ mentions (73%) of various support measures and strategies for inclusion. Students often mention their school well-being (88%), contrasting with only 25% of parents (figure 3).

Category 4: Options for fulfilling academic performance requirements

Students appreciate school when their favorite subjects are taught, and they receive praise. Consideration in physical education or exam scheduling can greatly support their performance. During absences, children wish to receive essential information and materials, have time to catch up upon returning to school, and receive support

.…the teacher was very kind and, yes, also conducted physical education in a way that was fair for me (I07_S_34).

Parents mention the necessity of considering the child’s current condition, for example, in physical education or exams, so that the children can perform adequately. There is fear of not receiving materials during long absences, being unable to catch up on missed work, not understanding the curriculum, or having no opportunity to ask questions. They wish for adequate time for the ill children to make up for missed work, adjustments in assessment, or the availability of remedial classes. Legal options for accommodations should be explored to avoid a loss in the child’s academic progress

.…and then, of course, he could never bring the same performance as the other children, well, if there was a bit more sensitivity to the whole thing, then that would be nice (I04_E_27).

Teachers believe that every student should give their best. Most students are highly motivated and ambitious, and the illness does not limit their performance. Possible impacts of the illness, such as concentration, writing ability, or distractibility, are taken into consideration in the classroom and all teachers should be informed about them. During absences, students often catch up on content independently, sometimes through home schooling or in clinic schools, with learning materials provided. Upon return to school, teachers support students through personal assistance or remedial classes. Exceptions in grading may be necessary for severely ill children

.…there are so many legal regulations that must be followed, and I always think, for such children, exceptions should actually be possible, and we should just overlook them and be done with it (I04_L_33).

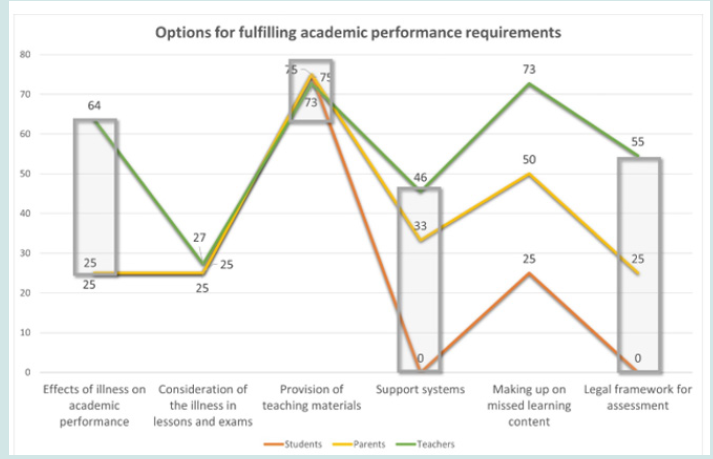

Addressing possibilities for fulfilling academic performance in school, teachers strongly perceive the impact of the illness on academic performance (64%). Support systems and legal frameworks are also frequently mentioned. However, students and parents are less aware of these points. There is a large overlap in the point provision of teaching materials during absences. This seems to be relevant for all groups (figure 4).

Category 5: Communication

Children wish for understanding from teachers, classmates, and school doctors. They would talk about the illness so that everyone is informed about what to do if they don’t feel well. Parents mainly contribute to educating people about the illness, with medical professionals being rarely involved.

I would find it really cool if it were done, if, for example, a child in a class has an illness, that the child could give a presentation or something about the illness and tell the class about it (I11_S_34).

Parents desire not to be in a position of supplication but rather seek the school’s interest in regular conversations. In these discussions, the illness, its effects, emergency measures, or different perspectives can be addressed. Written guidelines or emergency plans also help achieve an understanding of the child’s behavior and reduce fear of emergencies. Some teachers are open to this, while others are not, causing concern for parents. Therefore, parents often weigh whether to disclose information about the illness, fearing potential disadvantages for their children. They desire close communication and notification of special incidents in the class. Equally important is the education of classmates, so that children are not excluded, and everyone is informed about what to do in case of an emergency.

Well, at least the teacher who is responsible should know. In elementary school, there is mainly one contact person. We actually kept it that way; we had the teacher discussion at the beginning before school started, informed about the illness and what the teacher should know and can do or maybe support if there is an emergency (I09_E_14).

For teachers, parents are the primary source of information, with medical professionals or other sources rarely consulted. Parents should always be accessible and available for questions. An initial, open conversation about the illness, its effects, and emergency measures is desired. Teachers should also be regularly informed about incidents at home or absences. The child can also share information about the illness in their own class. Classmates are a valuable resource for assisting the affected child. Maintaining contact with parents is crucial and language barriers pose a challenge. Internally, there should be coordination among all colleagues, discussing emergency plans and providing mutual support. Communication among all directly and indirectly involved parties should be actively pursued.

I believe that it mostly depends on talking to each other, yes because many things are possible if you just ask (I08_L_59).

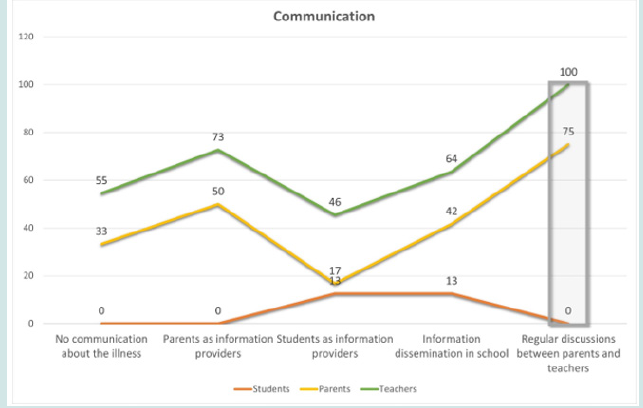

Teachers and parents frequently mention the need for regular exchange, while students do not mention communication among themselves at all (figure 5).

Discussion

In addressing the challenges arising from illnesses in students, several important considerations have emerged. Parents and students perceive diverse consequences of the illness in daily life, which are also significant in the school context. However, teachers may not perceive these stress factors in affected children in the same way as the children themselves or their parents do. This underscores the importance of effective communication among all stakeholders, particularly with the affected student. Teachers generally make considerable efforts to properly integrate students with illnesses. Students, in general, view school positively and describe it as something normal, without contemplating issues of social exclusion or the need for adjustments in teaching or exams due to the illness. Instances of exclusion are rarely mentioned. In contrast, parents express significant fears regarding potential exclusion or performance-related disadvantages for their children. Nevertheless, teachers also voice concerns in dealing with the illness. It is crucial to acknowledge and exchange these fears and concerns among parents and teachers. Additionally, raising awareness among teachers and classmates about the illness can counteract social and performance-related exclusion and fears [22].

Equally crucial for teachers are various support measures to implement therapeutic interventions in the school setting. Teachers require organizational support or collaboration with external institutions. Beyond knowledge of support measures – such as the presence of supportive personnel – teachers should be well-informed about legal options for adjusting teaching and examination performances. Teachers frequently perceive the impact of the illness on academic achievements and are willing to adjust support students in their academic journey. This includes effective absenteeism management, such as providing teaching materials during absences. Based on these findings, the recommended approach in the school setting upon the disclosure of an illness involves holding an intake meeting where teachers, parents, and affected students discuss the illness and its academic implications comprehensively. Legal issues, questions about adjusting the curriculum (especially in sports and excursions), and emergency management could be collectively addressed. Additionally, medical professionals or psychologists could provide further insights. It is particularly significant that affected students are allowed to communicate their individual needs to feel comfortable in school, as emphasized by Lum et al. [23]. Such a collaborative approach aims to improve academic performance as well. Checklists for teachers can simplify the documentation of results.

Teacher training is crucial in this context, as emphasized by Damm [24]. This training sensitizes teachers to the impacts of illnesses and enables them to better address the needs of students with illnesses on legal, methodological/didactic, and social levels. Scheduled follow-up discussions involving all parties allow teachers to stay informed about the current developments regarding the illness. Simultaneously, parents can receive information about the social and performance-related aspects of their child. Children and teachers have the opportunity to convey a more positive perception of school to parents. The regularity of such discussions could prevent many obstacles in advance, shifting parents away from the role of petitioners. Derived from this, future research projects would benefit from a larger sample size and a broader spectrum of illnesses. Long-term developments could also be documented to identify additional essential criteria for supporting students with illnesses in schools. It is evident that children do not prioritize consideration of the illness when discussing a normal school day. They want to experience school as normally as possible. Parents desire their children to feel comfortable in school without being treated differently from the rest of the students. For teachers, parental trust, information about the illness, and the availability of support are crucial components for effectively caring for students in school.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

I thank all the children and adolescents, their parents, and teachers for their open and honest words during the interviews.

References

- Etschenberg K (2001) Chronische Erkrankungen als Problem und Thema in Schule und Unterricht: Handreichung für Lehrerinnen und Lehrer der Klassen 1 bis 10. Wien: Bundeszentrum für gesundheitliche Aufklärung.

- Felder-Puig R, Teutsch F, Winkler R (2023) Gesundheit und Gesundheitsverhalten von österreichischen Schülerinnen und Schülern. Ergebnisse des WHO-HBSC-Survey 2021/22, Wien: BMSGPK.

- Edwards D, Noyes J, Lowes L, Haf Spencer L, Gregory JW (2014) An ongoing struggle: a mixed-method systematic review of interventions, barriers and facilitators to achieving optimal self-care by children and young people with Type 1 Diabetes in educational settings. BMC Pediatrics 14: 228.

- Damm L (2015) Kinder mit chronischen Erkrankungen in der Schule. Schriftenreihe der Volksanwaltschaft 3 :3-48.

- Landolt MA, Valsangiacomo Buechel ER, Latal B (2008) Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents after open-heart surgery. J Pediatr 152(3): 349-55.

- van Oers HA, Haverman L, Limperg PF, van Dijk-Lokkart EM and Maurice-Stam H et al. (2014) Anxiety and depression in mothers and fathers of a chronically ill child. Matern Child Health J 18(8): 1993-2002.

- Cockett A (2012) Technology dependence and children: a review of the evidence. Nurs child young people 24(1): 32-5.

- Hoffmann I, Diefenbach C, Gräf C, König J, Schmidt MF (2018) for the ikidS Study Group. Chronic health conditions and school performance in first graders: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 13(3): 1-15.

- Lum A, Wakefield CE, Donnan B, Burns MA and Fardell JE et al. (2017) Understanding the school experiences of children and adolescents with serious chronic illness: a systematic meta-review. Childcare Health Dev 43(5): 645-62.

- Hedderich I, Tscheke J (2013) Auswirkungen chronischer körperlicher Erkrankungen auf Schule und Unterricht. In: Pinquart M, Editor. Wenn Kinder und Jugendliche körperlich chronisch krank sind. Berlin: Springer: 119-133.

- Damm L (2015) Kinder mit chronischen Erkrankungen in der Schule. Schriftenreihe der Volksanwaltschaft 3: 3-48.

- DammL (2024) Chronisch kranke Kinder im Bildungswesen.

- Sommer N, Klug JL (2021) Krankheit in der Schule? Kein Problem! Zum Umgang mit Kindern mit chronischer Erkrankung im schulischen Handlungsfeld - konzeptionelle Bezugspunkte für eine Hochschulbildung. In: Holzinger A, Kopp-Sixt S, Luttenberger S, Wohlhart D, editor. Fokus Grundschule, Band 2. Forschungsperspektiven und Entwicklungslinien. Münster: Waxmann :329-40.

- Tolbert R (2009) Managing Type 1 Diabetes at School: An Integrative Review. J Sch Nurs 25(1): 55–61.

- Lum A, Wakefield CE, Donnan B, Burns MA and Fardell JE et al. (2017) Understanding the school experiences of children and adolescents with serious chronic illness: a systematic meta-review. Child Care Health Dev 43(5): 645–662.

- Sommer N, Erkrankungen Raum geben, Sommer N, Ditsios E (2022) Schule und chronische Erkrankungen. Grundlagen, Herausforderungen und Teilhabe Bad Heilbronn: Klinkhardt: 157-158.

- Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte Berlin, Deutsches Jugendinstitut e.V. München, Menschen Rechts Zentrum an der Universität Potsdam, Rochow-Museum und Akademie für bildungsgeschichtliche und zeitdiagnostische Forschung e.V. an der Universität Potsdam, editors. Reckahner Reflexionen zur Ethik pädagogischer Beziehungen.

- Sommer N, Klug JL (2021) Krankheit in der Schule? Kein Problem! Zum Umgang mit Kindern mit chronischer Erkrankung im schulischen Handlungsfeld – konzeptionelle Bezugspunkte für eine Hochschulbildung. In: Holzinger A, Kopp-Sixt S, Luttenberger S, Wohlhart D, editor. Fokus Grundschule, Band 2. Forschungsperspektiven und Entwicklungslinien. Münster: Waxmann : 329-40.

- Flick U (2011) Triangulation. Eine Einführung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Dresing T, Pehl T (2011) Vereinfachtes Transkriptionssystem nach Dresing & Pehl.

- Mayring P (2015) Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Verlag: 601-613.

- Sommer N, Erkrankungen Raum geben, Sommer N, Ditsios E (2022) editor. Schule und chronische Erkrankungen. Grundlagen, Herausforderungen und Teilhabe Bad Heilbronn: Klinkhardt: 157-158.

- Lum A, Wakefield CE, Donnan B, Burns MA and Fardell JE (2017) Understanding the school experiences of children and adolescents with serious chronic illness: a systematic meta-review. Child Care Health Dev 43(5): 645-62.

- Damm L Chronisch kranke Kinder im Bildungswesen.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...