Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Case Report(ISSN: 2637-4722)

Unusual Presentation of Myasthenia Gravis Volume 2 - Issue 2

Jeewan Rawal*, Olajumoke Davies and Shatha Al-ani

- Department of Paediatrics, Queen’s Hospital, UK

Received:April 01, 2019 Published: April 05, 2019

Corresponding author: Jeewan Rawal, Department of Paediatrics, Queen’s Hospital, Rom Valley Way, Romford, Essex, RM7 0AG, UK

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2019.02.000135

Abstract

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disorder causing skeletal muscle weakness, most commonly in the eyes, bulbar muscles, limbs, and respiratory muscles. Whilst it usually presents with ocular symptoms or dysarthria, dysphagia and fatigable chewing, our patient presented with difficulty in breathing, needing oxygen to maintain normal oxygen saturation. This case illustrates importance of considering uncommon causes for common presentations, when it does not fit in with the diagnosis.

Case Presentation

A 12 year old, previously fit & well girl, presented to A&E with h/o worsening Cough for 3 days and difficulty in breathing for 24 hours... She gave 2 week history of increased secretions in her throat and difficulty in swallowing. She felt her voice was ‘going funny’ and become ‘whispery’. She had been seen by her GP the week before who diagnosed allergy and treated her with cetirizine. Her symptoms improved slightly for 3 days but subsequently worsened. She had no significant perinatal, developmental, family or past medical history. She was up to date with immunisations. She was the first of two siblings and doing well at school. Initial examination in A&E by a Paediatric Consultant showed she was in obvious respiratory distress. with a respiratory rate of 34, with intercostal and subcostal recession, tracheal tug and reduced air entry at the right lower zone with widespread crackles and wheeze on both sides of the chest. CNS examination confirmed she was alert, GCS 15/15 with normal tone and reflexes. She had tachycardia with a heart rate of 118 bpm.

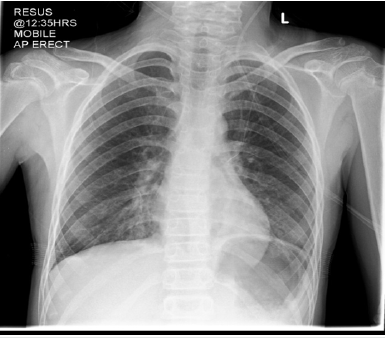

The rest of her systemic review was normal. She was able to eat and drink “normally” but bedside swallow was not formally assessed. She was treated for a respiratory tract infection with intravenous antibiotics and regular salbutamol nebulisers. A few hours later, she developed increased shortness of breath and a peri-arrest call was made. However, examination findings were unchanged, her management remained the same. Her bloods results were Hb 133, WBC 8.9, Plt 293, CRP 5, U&E NAD, LFT NAD. The CXR was reported as left lower lobe atelectasis with an increase of the peribronchial and perivascular interstitial infiltrates (Figure 1). she was reviewed by a second Paediatric Consultant in the ward later, who felt this was more likely to be an upper airway obstruction. He stopped the salbutamol nebulisers, continued the Atrovent nebulisers, started prednisolone and advised to suction intermittently, request an ENT review and arrange a neck X-ray and barium swallow. Neck X-ray was normal (Figure 1). An ENT Consultant reviewed the following day with flexible nasendoscopy which revealed a normal larynx, good vocal cord movement and very slight inflammation on the right arytenoid. The nasendoscopy findings were noted to be insufficient to explain the symptoms. The ENT impression was laryngopharyngeal reflux. She was put on Gaviscon Advance after food and before bedtime. she gradually improved over next three days. She was discharged home on Gaviscon Advance. Barium swallow, done a month later, was reported ‘the mid and distal oesophagus giving a shaggy appearance most likely due to Oesophageal Candidiasis’ (Figure 2).

In view of the barium swallow result she was referred to the Gastroenterologist at the tertiary unit for further investigation and 2 weeks later, underwent an oesophageo-gastro-duodenoscopy, which was normal. The barium swallow images were reviewed by a tertiary radiologist along with the gastroenterologist who raised concerns of aspiration and advised an immediate recall to review the patient. She was reviewed next day, on the pediatric ward. She looked well but continued to complain of ongoing painless dysphagia and muffled voice. A repeat CNS examination revealed bilateral facial weakness, bilateral ptosis with expressionless face, reduced palatal movement and muffled voice (Figures 3 & 4). A clinical diagnosis of Myasthenia gravis was made which was confirmed by EMG next day. Her Acetylcholine receptor antibodies were raised at 3.53 (normal range 0–0.45) confirming the diagnosis of Myasthenia Gravis. Anti-MuSK antibodies were negative. She was commenced on Pyridostigmine 120mg TDS. She was referred to tertiary Neurology unit, where she was admitted 3 weeks later due to deterioration of her symptoms. During this admission oral prednisolone was added to achieve remission. She continued to remain symptomatic, intermittent immunoglobulin infusions were added to her treatment and finally needed partial Thymectomy. She has improved a lot and at present is on Pyridostigmine and reducing regime of oral steroids.

Discussion

Myasthenia gravis is a syndrome characterized by fatigable muscle weakness caused by autoimmune damage at the neuromuscular junction. In children, the commonest presentation is with ptosis, followed by speech difficulty and hoarse voice. Presentation with any other symptoms is rare. Annual incidence OF Myasthenia Gravis is low (4-6/million [1]. Juvenile myasthenia accounts for only 2-3% of these [2], hence very uncommon condition in the pediatric population. However, one small study of 79 children found presentation with respiratory symptoms in 90% [3]. In our case we feel that clinicians were biased towards diagnosis of Asthma as it is much more common to cause acute respiratory distress. Her “difficult swallowing” and feeble voice was not taken seriously. We believe that her initial improvement on presentation was due to oral steroids. The normal chest and neck X-rays, normal blood values and a laryngeal inflammation explicitly noted to be “insufficient to cause her symptoms”. Even the clear contrast track in the right bronchial system was missed on barium swallow by the initial radiologist. It is only after her condition had progressed for a month, clinical picture became apparent to diagnose Myasthenia Gravis.

Our patient appears to be unique in the literature in her presentation with aspiration pneumonitis. Two cases with foreign body aspiration reported, one in an 8-year-old child2 and the other in a 20-month-old infant [4]. In the former [2] authors emphasize “the importance of considering an undiagnosed neurologic or neuromuscular disease as an underlying cause of foreign body aspiration, particularly if the clinical presentation is in an older child” [2]. This case emphasises the need to think laterally and consider uncommon conditions in the differential diagnosis of a child with a common presenting complaint like acute respiratory distress. This is particularly important if it does not fit with overall clinical scenario. In such cases, We should revisit, take a thorough history and do a full systemic examination including neurological examination.

References

- Vrinten C, van der Zwaag AM, Weinreich SS, Scholten RJ, Verschuuren JJ Verschuuren (2014) Ephedrine for myasthenia gravis, neonatal myasthenia and the congenital myasthenic syndromes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 17(12).

- David J Murray, John McAllister (2001) Foreign Body Aspiration: A Presenting Sign of Juvenile Myasthenia Gravis. Anesthesiology 95(2): 555-557.

- Lindner A, Schalke B, Toyka K (1997) Outcome in juvenile-onset myasthenia gravis: a retrospective study with long-term follow-up of 79 patients. J Neurol 244(8): 515-520.

- Phillips H Winter, Charles F Koopmann (1990) Juvenile myasthenia gravis: an unusual presentation. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 19: 213-276.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...