Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Mini Review(ISSN: 2637-4722)

Juvenile Myasthenia Gravis: A Short Review Volume 2 - Issue 1

Shubhankar Mishra*

- Department of Neurology, India

Received: November 26, 2018; Published: November 29, 2018

*Corresponding author: Shubhankar Mishra, Department of Neurology, India

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2018.02.000127

Abstract

Juvenile myasthenia gravis (JMG) is an autoimmune disorder of neuromuscular transmission caused by production of antibodies against components of the postsynaptic membrane of the neuromuscular junction. The patients present with a wide range of symptoms-from isolated intermittent ocular symptoms to general muscle weakness with or without respiratory insufficiency. Prepubertal children in particular have a higher prevalence of isolated ocular symptoms, lower frequency of acetylcholine receptor antibodies, and a higher probability of achieving remission. It must be differentiated from congenital myasthenia which is a channelopathy rather than autoimmune disease. Treatment commonly includes anticholinesterases, corticosteroids with or without steroid-sparing agents, and newer immune modulating agents. Plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) are effective in preparation for surgery and in treatment of myasthenic crisis.

Keywords: Myasthenia; Ptosis; Pyridostigmine

Abbrevations: JMG: Juvenile Myasthenia Gravis; IVIG: Intravenous Immunoglobulin; MG: Myasthenia Gravis; Ab: Antibodies; AChR: Acetylcholine Receptor; MuSK: Muscle-Specific Kinase; LRP4: Leucine Rich Protein 4; RNS: Repetitive Stimulation Test; SFEMG: Single Fiber Electromyography; CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Introduction

The first description of myasthenia gravis (MG) with onset in childhood originates from Erb in 1879 [1]. The definition of juvenile myasthenia gravis (JMG) includes infants, children, and adolescents aged 0 to 19 years [2]. JMG patients are subdivided according to the occurrence of the first symptoms as prepubertal (first symptoms before the age of 12 years) and postpubertal (first symptoms after the age of 12 years) [3]. The main action of disease is production of antibodies (Ab) against the components of postsynaptic membrane, predominantly the binding acetylcholine receptor (AChR). MG is divided into five groups: ocular myasthenia (grade I), mild (grade IIa), moderate (grade IIb), severe weakness other than ocular (grade III), and very severe weakness defined by intubation with or without mechanical ventilation (grade IV) [4]. It is a rare disorder of the childhood which accounts for less than 10- 15% with an incidence of 1-5 per million per year [2].

In Asian population, up to 50% of MG patients present with the first symptoms in childhood (age peak between 5 and 10 years); no difference in sex distribution has been observed. In this population, more than 70% of cases are restricted to ocular symptoms and benign course is common [2,5]. In post-pubertal children, the clinical course is similar to adult-onset MG. The patients frequently present with ocular symptoms at the onset; generalized-muscle weakness develops in up to 80% in the course of the disease [2].

Pathogenesis: In the majority of cases MG is caused by antibodies to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) which is found in over 80% adults with generalised disease but only in 55% of adults with weakness confined to the oculomotor muscles. Patients with AChR antibodies are often referred to as seropositive. AChR antibodies are probably less frequent in prepubertal patients than in adolescent and adult patients [6]. Antibodies to musclespecific kinase (MuSK) and to Leucine rich protein 4 (LRP4) have been reported in some seronegative patients.

Clinical Features: A typical clinical symptom of abnormal neuromuscular transmission is a fatigability that occurs acute or subacute. The first symptoms may develop as early as in the first year of life [7]. Generally, the developmental milestones are normal before disease onset. Clinical presentation depends on the muscle group affected: ocular problems such as ptosis or ophthalmoplegia, bulbar muscle weakness, respiratory muscle involvement, and proximal symmetrical muscle weakness. Ocular symptoms are common at onset. The definition of ocular MG is restricted to the ocular symptoms for 2 years without becoming generalized [8]. Ptosis usually aggravates after physical activity. It may be unilateral or bilateral. Children may complain about double vision. Sometimes, children may present having difficulties in climbing stairs because of diplopia. About 50% of children with ocular symptoms develop systemic or bulbar muscle involvement within 2 years after onset. If bulbar muscles are involved there will be nasal regurgitation. Symptoms depend upon weakness.

When generalized muscle weakness is there, patients have problems to walk a normal distance or to run, have difficulties in climbing stairs or to rise from a squatting position. In many conditions generalized muscle weakness, which presents as painless fatigability of the bulbar and limb musculature, with dysphonia, dysphagia, and proximal limb weakness. Children are at risk of choking or aspiration and are at increased risk of chest infection. Occasionally, impairment of the respiratory muscles necessitates ventilatory support. This is known as “myasthenic crisis”. In the physical examination, children may appear normal if examined after rest; repetitive assessment of muscle strength with standardized tests is recommended [9]. Transient neonatal myasthenia is a condition that results from transfer of maternal AChR antibodies across the placenta leading to defects of neuromuscular transmission in the neonate [10]. Not all mothers have detectable AChR antibodies and a few are asymptomatic at the time. Usually the affected baby is normal at birth, subsequently developing signs such as hypotonia, weak cry, poor suck, reduced movements, ptosis and facial weakness, and occasional respiratory insufficiency requiring mechanical ventilation. Short-term treatment with anticholinesterases is usually sufficient.

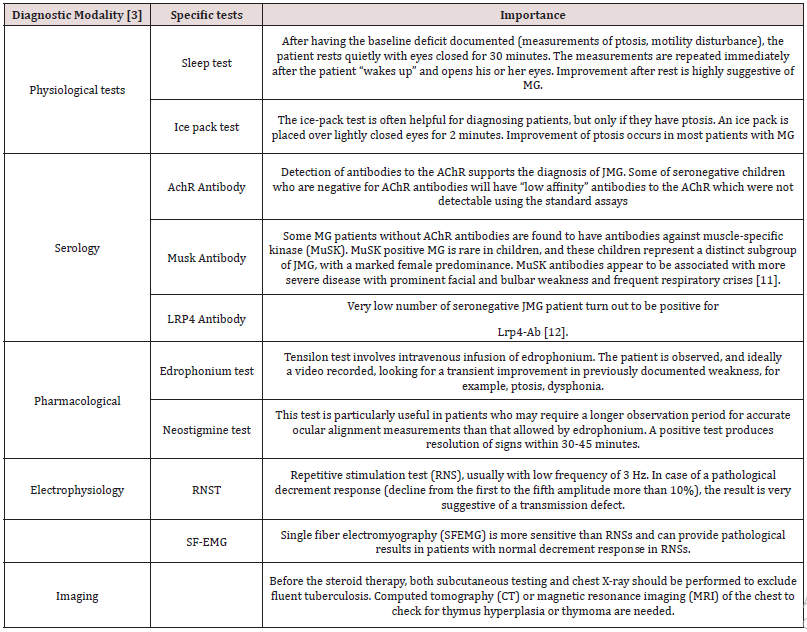

Diagnosis: (Table 1)

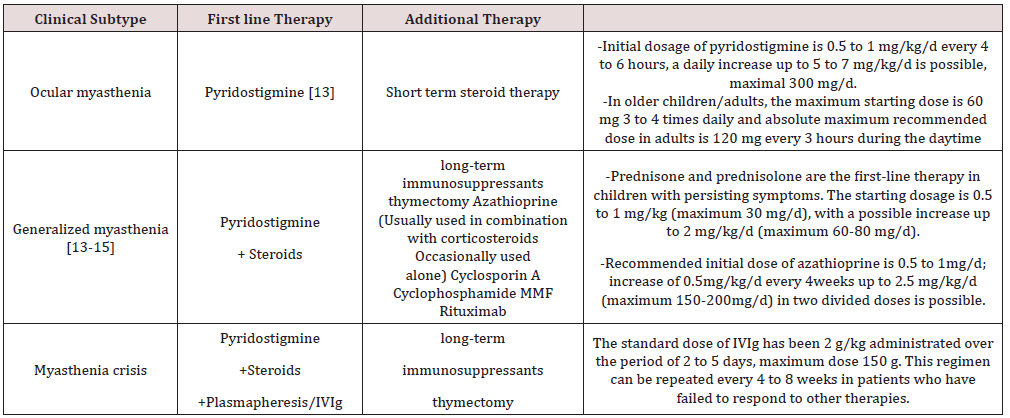

Treatment: (Table 2)

Conclusion

JMG is one of the subtypes of MG with very good prognosis and outcome. It has more ocular predominance then adult MG. Diagnosis is done by both serological and electrophysiological tests. Pyridostigmine is the primary modality of management. Early diagnosis and management can save many patients from acute crisis. To some extent, treatment options for adults may be adapted for children, but specific pathophysiology differences must be considered in this population group.

References

- Erb W Zur Kasuistik der bulbaeren Lähmungen (1879) Ueber einen neuen, wahrscheinlich bulbaeren Symptomen komplex. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 9: 336-350.

- Evoli A (2010) Acquired myasthenia gravis in childhood. Curr Opin Neurol 23(5): 536-540.

- Finnis MF, Jayawant S (2011) Juvenile myasthenia gravis: a paediatric perspective. Autoimmune Dis: 404101.

- Osserman KE, Genkins G (1971) Studies in myasthenia gravis: review of a twenty-year experience in over 1200 patients. Mt Sinai J Med 38(6): 497-537.

- Chiu HC, Vincent A, Newsom-Davis J, Hsieh KH, Hung T (1987) Myasthenia gravis: population differences in disease expression and acetylcholine receptor antibody titers between Chinese and Caucasians. Neurology 37(12): 1854-1857.

- Andrews PI, Massey JM, Howard JF, Sanders DB (1994) Race, sex, and puberty influence onset, severity, and outcome in juvenile myasthenia gravis. Neurology 44(7): 1208-1214.

- Chiang LM, Darras BT, Kang PB (2009) Juvenile myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 39(4): 423-431.

- Luchanok U, Kaminski HJ (2008) Ocular myasthenia: diagnostic and treatment recommendations and the evidence base. Curr Opin Neurol 21(1): 8-15.

- Besinger UA, Toyka KV, Hömberg M, Heininger K, Hohlfeld R, et al. (1983) Fateh-Moghadam A. Myasthenia gravis: long-term correlation of binding and bungarotoxin blocking antibodies against acetylcholine receptors with changes in disease severity. Neurology 33(10): 1316-1321.

- Tellez-Zenteno JF, Hernandez-Ronquillo L, Salinas V, Estanol B, da Silva O (2004) Myasthenia gravis and pregnancy: clinical implications and neonatal outcome. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 16(5): 42.

- Vincent A, Leite MI. (2005) Neuromuscular junction autoimmune disease: muscle specific kinase antibodies and treatments for myasthenia gravis. Current Opinion in Neurology 18(5): 519-525.

- Pevzner A, Schoser B, Peters K, Cosma NC, Karakatsani A, et al. (2012) Anti-LRP4 autoantibodies in AChR- and MuSK-antibody-negative myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 259(3): 427-435.

- McMillan HJ, Darras BT, Kang PB (2011) Autoimmune neuromuscular disorders in childhood. Curr Treat Options Neurol 13(6): 590-607.

- Ionita CM, Acsadi G (2013) Management of juvenile myasthenia gravis. Pediatr Neurol 48(2): 95-104.

- Ware TL, Ryan MM, Kornberg AJ (2012) Autoimmune myasthenia gravis, immunotherapy and thymectomy in children. Neuromuscul Disord 22(2): 118-121.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...