Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4722)

Dietary Patterns in A Romanian Children Population with Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Volume 4 - Issue 1

Iulia Florentina Ţincu1,2, Ioana Maria Otilia Lică1,2*, Delia Bogheanu3, Anamaria Renata Luca1 and Doina Anca Pleșca1,2

- *1“Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Paediatrics and Genetics, Discipline of Paediatrics, Bucharest, Romania

- *2“Dr. Victor Gomoiu” Clinical Children Hospital, Department of Paediatrics, Bucharest, Romania

- 3“St. John” Clinical Emergency Hospital, Bucharest, Romania

Received: January 03, 2023 Published: January 10, 2023

Corresponding author: Lică Ioana Maria Otilia, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Paediatrics and Genetics, Discipline of Paediatrics, and “Dr. Victor Gomoiu” Clinical Children Hospital, Paediatrics Department, Bucharest, Romania

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2023.04.000180

Abstract

Background

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are complex conditions, resulting from the interactions between genetic, environmental, alimentary, psychological, socio-cultural factors and the interaction of the brain-gut axis. Gastrointestinal functional disorders (FGID) affect a significant percentage of school-age children worldwide, with approximately 1 in 4 children in the general population. The chronic and debilitating nature of symptoms is a major concern in paediatrics by reducing the quality of life of patients and their families and the financial burden on them.

Aims

The present paper aimed to identify the dietary peculiarities in children diagnosed with FGID, older than 4 years, in a year of pandemic, in contrast to the eating habits of those in the general population, in order to highlight their role in FGID.

Materials and Methods

A total of 341 subjects were included in the study, 278 met the criteria for inclusion in the group with FGID (81.52%) and 63 (18.48%) in the control group. The 63 participants from the control group were chosen by distributing the questionnaires of the patients presented for acute conditions without chronic diseases and FGID.

Results

According to BMI, FGIDs patients were more likely to be both underweight and overweight. In a regression model, more frequently consumption of fast and junk food and sugar intake was associated with the occurrence of the FGIDs (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00-1.66, OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.4-2.1, OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.98-1.81, resources), but also a high sugar intake increases the risk to belong to the FGID group (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.004-1.215).

Conclusions

Underweight, overweight, average socio-economic conditions, very rare physical activity, consumption of dairy, carbonated juices and junk food are positively associated with the probability of FGID occurrence.

Keywords: Functional gastrointestinal disorders; dietary pattern; lifestyle

Introduction

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) represent a group of chronic and recurrent symptoms in the absence of any organic proven disorder [1]. There are several factors involved in the pathogenesis, although no single cause could be identified and addressed properly, like motility disturbances, genetic implications, environmental factors, visceral sensitivity, psychologic alterations, and gut-brain disturbances [2]. The diagnostic criteria are standardized according to ROME IV definitions that empower the clinician to apply various definitions considering the age, clinical remarks, and time evolution. Of course, several other intolerances and metabolic disorders should be kept in mind according to history and clinical evaluation, as literature data had communicated some co-existence of several pathologies [3]. The benefit of using standardized unitary criteria is that they provide a non-invasive attitude towards the patients, skipping some additional investigations if there is no alarm sign in patient evolution. Nevertheless, highly symptomatic patients, especially with abdominal pain disorders, do experience important investigations regarding costs and time spent in the hospital; they are a great source of school absenteeism with lower scores for life quality [4]. Data shown from MEAT study on the Mediterranean region of Europe identified FGIDs in 20.7% of children aged from 4 to 10 years and in 26.6% of children aged 11-18 years.

Not only the incidence is of great concern, but also the treatment. Most practitioners apply symptoms target therapy, either central or peripheral action, but long-term consolidations is still an issue because patients often experience a clinical relapse of the disease. In general terms, treatment can be addressed to pain reliever, intestinal microbiota, cognitive behavioral therapy, stool consistency, or nutrition intervention. There is a great need for a more integrated unitary paediatric gastroenterological practice for FGIDs in children. Some treatment techniques, like cognitive, psychological, or behavioral therapy, are prohibitive due to costs and facilities. Consecutively, self-treatment is a frequent practice in these patients, and food interventions are the most appropriate used, due the self-perceptions of a food adverse reaction. Indeed, up to 60% of FGIDs patients describe gastrointestinal symptoms shortly after food ingestion [5]. Previous data have shown some impact of diet on the etiopathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Functioning the gastrointestinal tract, such as microbiome, barrier function, absorption, motility, and sensitivity as well if modulated by nutrient ingestion [6]. We were interested in children with FGIDs dietary patterns and if they do get information about their food habits to improve symptoms. The aim of the present population-based study was to determine the meal patterns, daily activity, and emotional/behavioral patterns in children with FGIDs.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a cross-section study aimed to evaluate dietary patterns of children with FGIDs aged 4-18 years old, fulfilling the criteria of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents. The research took place in the „Dr. Victor Gomoiu” Clinical Children Hospital, from Bucharest, the capital of Romania, and participants were enrolled all over the pandemic year 2020.

Study Population

Each proposed eligible patient was invited to discuss the study follow-up in detail with researchers and subsequently he/she was assigned according to ROME IV criteria to one of the categories: cyclic vomiting, functional nausea, functional vomiting, rumination syndrome, aerophagia, functional dyspepsia, diarrhea predominant (IBS-D), constipation predominant (IBS-C), abdominal migraine, functional constipation, and non-retention faucal incontinence. Patients were excluded if they had abnormal biochemical markers and if they had abnormal findings on various procedures in the previous medical visits like in barium enema or colonoscopy. The healthy group for comparison was enrolled from children addressed for regular medical evaluation, free of symptoms or chronic illness, within the same age interval and having similar socio-demographic characteristics.

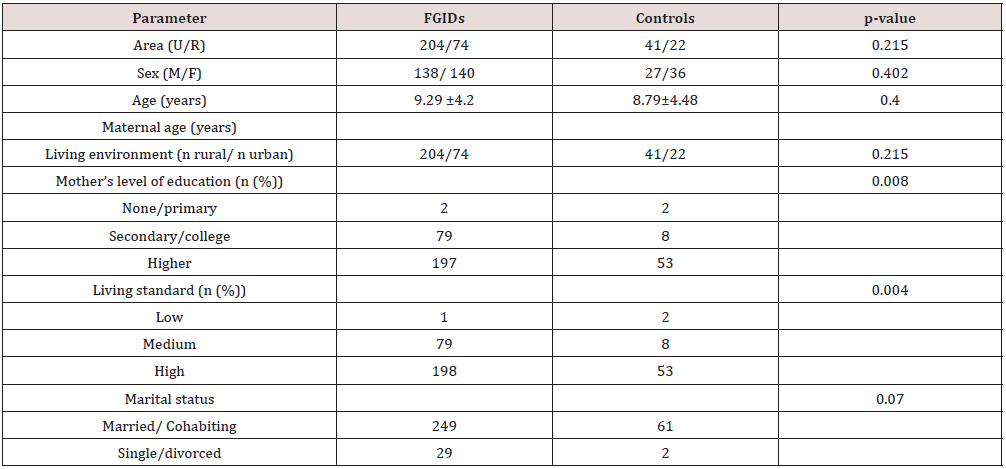

Social-demographic Data

Data recorded initially provided information about patient’s age, mothers’ age, residence (urban vs. rural), parental level of education (Higher: higher education; secondary/college: highschool, 8 classes; None/primary: none or 4 classes), declared living standards (the average income per family member) throughout the previous six months were taken into consideration: low, medium, or high, marital status: married/ cohabiting or single/divorced.

Dietary Habits

Food intake was assessed using the food frequency questionnaire, consisting of 98 questions concerning on usual food use and meal patterns at home and school during weekdays [7]. We were particularly interested in fruit, vegetables, junk food, and sweetened drinks consumption in terms of frequency and parents had to report choosing from variants: daily, between 3 to 5 times per week, or less than 3 times per week. The meal patterns during family spent time were also addressed in terms of frequency, and regular versus irregular type of nutrition was also noted.

Lifestyle Pattern

Physical activity and daily time spent on media was a part of the questionnaire; parents had to choose between: daily, between 3 to 5 times per week, less than 3 times per week for physical activity and the options for media exposure was less than 2 hours, between 2 to 4 hours and more than 4 hours. There were no criteria regarding the intensity of physical activity.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital under the registration numbered as 20239/17.12.2019. Permission was required before each interview took place.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was based on SPSS for Windows (ver. 18.0; SPSS) using Student’s tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. We used the corresponding 95% CI for each disorder prevalence, obtained using the procedure first proposed by Clopper and Pearson [8]. The ANOVA comparisons were confirmed with Mann–Whitney U-tests. Correlations among the continuous variables were performed with Pearson and Spearman rank correlation coefficients. Results were considered statistically significant when the p values were <0.05.

Results

Subjects and Baseline Characteristics

U-urban; R-rural; n-number.

During pandemic year 2020, 11 049 patients were accorded medical help in our hospital, out of which the final cohort consisted in 341 subjects, 278 assigned as FGIDs group and 63 assigned as controls group, respectively. The distribution according to subtypes of FGIDs revealed: 3 patients with aerophagia, 29 patients with functional constipation, 61 patients with functional dyspepsia, 15 patients with abdominal migraine, 10 patients with rumination syndrome, 42 patients with IBS-D, 64 patients with IBS-C, 31 patients with abdominal pain non classified. Demographic characteristics according to positive diagnosis of FGIDs is shown in Table 1.

Anthropometric Data

According to BMI, FGIDs patients were more likely to be both underweight and overweight. According to growth charts analysis, 11.2% were underweight, 19.8% over-weight and 1.4% were obese.

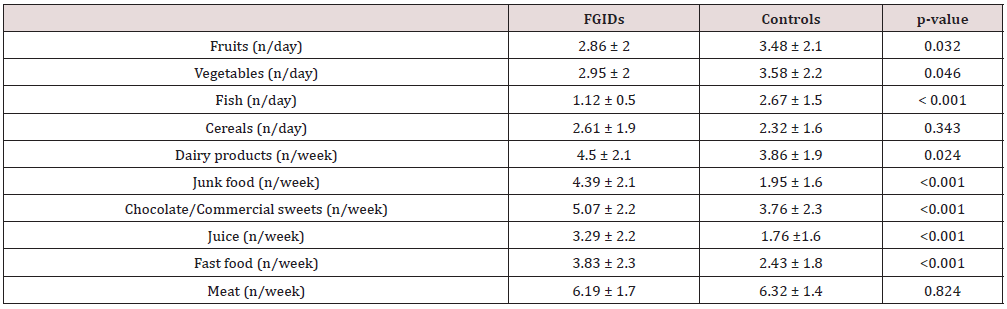

Dietary Intake

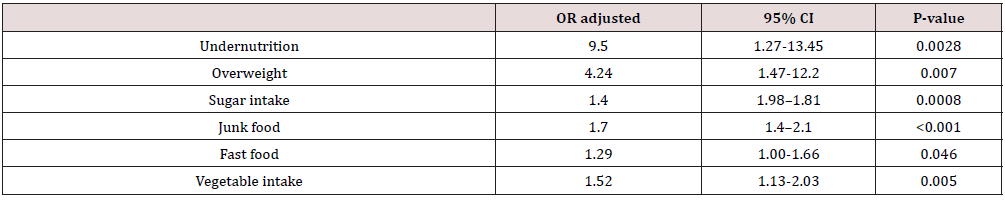

According to maternal declaration, patients with FGIDs use more frequently sweetened beverages, processed sweets, fast food and junk food in their daily habits than control group, while they have a lower consumption of fruit and vegetable. Meat and cereals intake did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 2). In a regression model, more frequently consumption of fast and junk food and sugar intake was associated with the occurrence of the FGIDs (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00-1.66, OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.4-2.1, OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.98-1.81, resources), but also a high sugar intake increases the risk to belong to the FGID group (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.004-1.215) (Table 3).

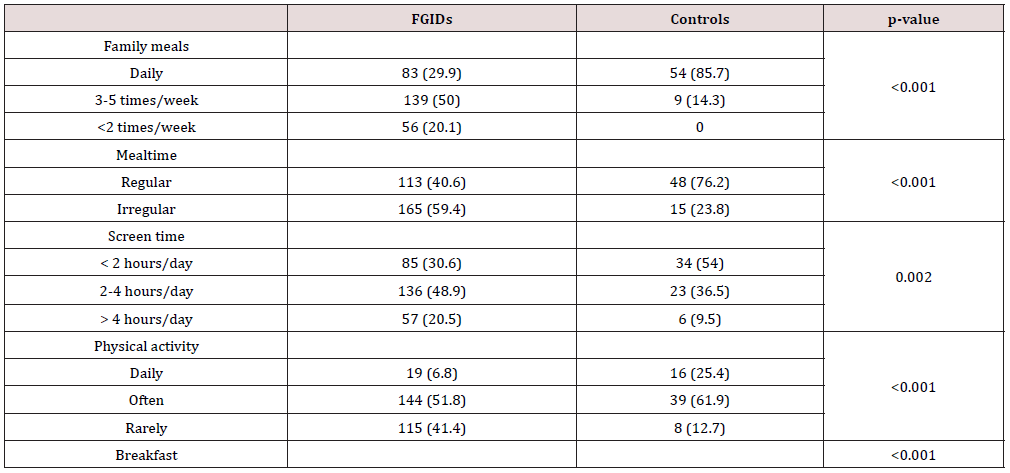

Lifestyle Pattern

Children with FGIDs spent more time on media screen weekly, had less hours of physical activity, do have irregular meals, do not spent time with family during mealtimes and more frequently skip breakfast (Table 4).

Discussion

The interaction of food with the digestive tract is complex. The percentage of proteins, lipids and carbohydrates in the diet controls the gastrointestinal release of hormones, thus influencing motility, gastric secretion and absorption, cell proliferation, appetite, and local immune response, while integrating the enteric, autonomic, and central nervous systems [9]. They also have an impact on the microbiota. In this regard, the role of the diet in FGID is a topic of interest often manifested in studies. As FGID are multifactorial conditions, we tried to determine the parameters that could contribute to their appearance, rather than trying to find a single associated agent. The present study showed, analyzing strictly the diet, that certain eating habits are more common in children with FGID than in those in the control group, especially the increased consumption of junk food (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4- 2.1; p<0.001) and the reduced consumption of fish (OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.262- 0.488, p <0.001), along with a high consumption of dairy products (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1-1.44; p=0.042) and carbonated juices ( OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1-1.5; p=0.036). However, when in the equation of multivariate analysis on stages it was also taken into account the other parameters that were demonstrated the association with the appearance of FGID (socio-economic factors, demographics, meal regime, level of physical activity and breakfast consumption), in addition to the before mentioned foods, the results showed an involvement in the probability of the occurrence of FGID and other foods: vegetables (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.13-2.03, p= 0.005), sweets (OR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.09-1.81, p= 0.008) and fast food (OR 1.29; 95% CI, 1-1.66, p= 0.046).

Thus, in the pathogenesis of FGID, in addition to eating habits, factors related to the environment in which the child develops, the level of activity, as well as the characteristics of the diet must also be considered. Avoiding foods rich in fermentable oligosaccharides is an effective approach to the management of digestive symptoms within FGID [10]. Also, the improvement in symptoms was highlighted in a study on children with irritable bowel syndrome [11] and by reducing even just one food carbohydrate such as lactose, sorbitol, or fructose. Some previous studies have shown potential benefits of oligofructose and inulin in chronic non-specific diarrhea, but this was appliable in younger ages [12]. In the present study the intake of fermentable oligosaccharides and disaccharides in the form of vegetables, and dairy was reported more frequently in the group with FGID than in the control one. Although the study did not evaluate the exact amounts in which they are consumed, it is important to take this into account in potential future studies as well. It is also important the composition of foods in terms of the ratio existing between the constituent carbohydrates of the food because there can be interactions between them so that their further absorption and implicitly the effects on the digestive symptoms are influenced.

An example of this is the excess of fructose compared to glucose, called free fructose, which in the absence of glucose has a slower absorption that will cause lumen distension through the active osmotic effect [13]. A potential mechanism involved is the effect of chemicals (salicylate, amines, glutamate) contained in carbonated juices on the enteric nervous system, but also on the intestinal microbiota. A high consumption of carbonated juices, in the batch with FGIDs compared to the control group, we also found in the present study, when analyzing only the food consumed, with the mention that when considering the environmental factors, it lost its statistical significance. But the new model, in which the aforementioned factors were also considered, showed a high consumption of sweets in patients with FGIDs, for which the mechanisms for producing symptoms are similar to those of carbonated juices, through the effect on the microbiota [14], through the content of chemicals such as salicylates, amines and glutamate, but also the content rich in polyols.

We found a statistically significant correlation between junk food consumption and FGIDs as well. There aren’t very many articles that follow this relationship. A 2034 study of subjects in Taiwan reported high junk food consumption among subjects with FGIDs [15]. The consumption of junk food brings a high intake of salt, saturated fatty acids, preservatives, processed carbohydrates [16]. Possible explanations of the connection of junk food consumption with digestive symptomatology are the involvement of the lipids in their content in the accentuation of intestinal motility [17] and the influence of the intestinal microbiota by increasing the ratio between gram negative and gram-positive bacteria [18]. Fish consumption reported in the participants of the FGID group is reduced compared to the control group, in line with the results of other studies that claim that irritable bowel syndrome patients have a modified lipid profile and low levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids, fish being an important source of such acids. Another study relevant to support this hypothesis is published by Alfven and Strandvik [19], in which omega-6 pro-inflammatory fatty acids, nociceptive, are in greater quantity than omega-3 anti-inflammatory acids, considered antinociceptive, in patients with recurrent abdominal disorders than in healthy ones.

A statistically significant correlation between high fast-food consumption and FGIDs was also found, like other studies that tracked the relationship between fast food and FGIDs risk. An example of such a study was conducted in 2016, on 2042 adolescents with at least one functional gastrointestinal disorder, in which a fastfood consumption of 88.1% was reported, demonstrating a positive association with the development of FGIDs. The mechanisms involved are not clearly known, but it is possible that an important role is played by the high content of lipids, sodium, trans fatty acids of fast food that causes the reduction of intestinal motility and enables the reflux episodes [20], but also through the impact on the immunity of the intestinal mucosa [21]. After analyzing the anthropometric data, we found a positive association between overweight subjects and FGIDs, with a much higher probability for them to have FGIDs, compared to those in the control group (OR, 4.24; 95% CI, 1.47- 12.2; p= 0.007). This association between weight above normal and FGIDs was also demonstrated in a 2014 study of 450 children. We also found a positive association between the underweight participants and the FGID (OR, 9.5; 95% CI, 1.27- 71.5; p= 0.028).

The multivariate phased analysis carried out in this study does not exhaust the possible interactions between the factors that describe the child’s living environment, his level of activity, his or her consumption or not of breakfast and the food consumed, but shows that when taken as a whole, the results on FGIDs predictors change, compared to their individual analysis. In view of the fact that subjects with a certain socio-economic profile and certain eating habits present FGID, we can point out that an approach from the perspective of the biopsychosocial model is important in order to better understand these complex pathologies. Also, the exact amounts of food consumed have not been determined, beyond which they become involved in digestive symptoms in FGID. These are aspects that would be worth following because diets that go on the exclusion of foods associated with FGID symptoms can become far too restrictive and have a negative impact on a child in the process of development [22].

Limitation of the Study

Causal inference is not possible because this is not longitudinal data. The study did not analyze other factors such as psychosocial features, family history of functional disorders and nutritional intake of the patient that might have a cumulative impact of the prognosis. Knowledge of supplementary data could allow a better understanding of the mechanisms and treatment options.

Conclusion

The research was carried out in the pandemic conditions of 2020, so the data cannot be extrapolated to all children affected by FGIDs. Underweight, overweight and obesity, the average socioeconomic conditions are positively correlated with the classification in the group with FGIDs. We have also noticed the involvement of daily physical activity, so sedentary children often associate FGIDs. Analyzing only the foods tracked in the questionnaire, we kept as predictors the consumption of dairy, carbonated juices, and junk food these being positively associated with the probability of the occurrence of FGIDs. In view of the fact that subjects with a certain socio-economic profile and certain eating habits present FGIDs, we can point out that an approach from the perspective of the biopsychosocial model is important in order to better understand these complex pathologies. Some ongoing studies should address dietary content in relation to FGIDs in children.

Acknowledgments

No

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization: I.F.Ț. and D.A.P.; methodology, I.F.Ț.; software D.B.; validation, I.F.Ț., D.B. and D.A.P; formal analysis and statistics, I.F.Ț.; investigation, D.B. and A.R.L; resources, I.F.Ț.; data curation, D.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B. I.M.O.L, and A.R.L.; writing—review and editing, I.F.Ț and I.M.O.L.; visualization, A.R.L.; supervision, D.A.P.; project administration, I.F.Ț. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Koppen IJ, Nurko S, Saps M, Di Lorenzo C, Benninga MA (2017) The pediatric Rome IV criteria: what's new? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11(3): 193-201.

- Scarpato E, Kolacek S, Jojkic-Pavkov D, Konjik V, Živković N, et al. (2017) Prevalence of Functional gastrointestinal Disorders in children and adolescents in the Mediterranean region of Europe. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 16(6): 870-876.

- Daniela Pǎcurar, Gabriela Leşanu, Irina Dijmǎrescu, Iulia Florentina Tincu, Mihaela Gherghiceanu, et al. (2017) Genetic disorder in carbohydrates metabolism: hereditary fructose intolerance associated with celiac disease. Rom J Morphol Embryol 58(3): 1109-1113.

- Youssef NN, Murphy TG, Langseder AL, Rosh JR (2006) Quality of life for children with functional abdominal pain: a comparison study of patients’ and parents’ perceptions. Pediatrics 117(1): 54-59.

- Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, Svedlund J, Abrahamsson H, et al. (2001) Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion 63(2): 108-115.

- Korterink J, Devanarayana NM, Rajindrajith S, Vlieger A, Benninga MA (2015) Childhood functional abdominal pain: Mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 12(3): 159-171.

- Matos SM, Prado MS, Santos CA, D Innocenzo S, Assis AM, et al. (2012) Validation of a food frequency questionnaire for children and adolescents aged 4 to 11 years living in Salvador, Bahia. Nutr Hosp 27(4): 1114-1149.

- Clopper CJP, Pearson ES (1934) The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika 26(4): 404-413.

- El-Salhy Magdy (2019) Nutrional Management of Gastrointestinal Diseases and Disorders. Nutrients 11(12): 3013.

- Gibson Peter R, Shepherd Susan J (2010) Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25(2): 252-258.

- Iacocvou, Marina (2017) Adapting the low FODMAP diet to special populations: infants and children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 32(1): 43-45.

- Cristina Adriana Becheanu, Iulia Florentina Ţincu, Roxana Elena Smădeanu, Oana Andreia Coman, Laurentiu Coman, et al. (2019) Benefits of oligofructose and inuline in management of functional diarrhoea in children – interventional study. Farmacia 67(3): 511-516.

- Gibson Peter R, Shepherd Susan J (2012) Food Choice as a Key Management Strategy for Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 107(5): 657-666.

- Gomes de Moraes Joyce, Maria Eugênia Farias de Almeida Motta, Monique Ferraz de Sá Beltrão, Taciana Lima Salviano, Giselia Alves Pontes da Silva (2016) Fecal Microbiota and Diet of Children with Chronic Constipation. Int J Pediatr 2016: 6787269.

- Giorgos C, Kondyli C, Bouzios I, Spyropoulos N, Chrousos GP, et al. (2019) Dietary Habits and Abdominal Pain-related Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A School-based, Cross-sectional Analysis in Greek Children and Adolescents. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 5(1): 113-122.

- Chapman Gwen, MacLean Heather L (1993) “Junk food” and “healthy food” meanings of food in adolescent women's culture. J Nutri Edu 25(3): 108-113.

- Feinle-Bisset Christine, Azpiroz Fernando (2013) Dietary Lipids and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 108(5): 737-747.

- Dore J, Blottiere H (2015) The influence of diet on the gut microbiota and its consequences for health. Curr Opin Biotechnol 32: 195-199.

- Alfven G, Strandvik B (2016) Antinociceptive fatty acid patterns differ in children with psychosomatic recurrent abdominal pain and healthy controls. Acta Paediatrica 105(6): 684-688.

- Shau JP, Chen PH, Chan CF, Hsu YC, Wu TC, et al. (2016) Fast food - are they a risk factor for functional gastrointestinal disorders? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 25(2): 393-401.

- Myles Ian A (2014) Fast food fever: reviewing the impacts of the Western diet on immunity. Nutri J 13(61): 1-17.

- Phatak UP, Pashankar DS (2014) Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in obese and overweight children. Int J Obes 38(10): 1324-1327.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...