Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-4722)

A Clinical Decision Support System for Maternity Risk Assessment Developed for NHS Scotland Volume 1 - Issue 5

Yaëlle Chaudy1*, Thomas M Connolly1 and Brian Magowan2

- 1School of Computing, University of the West of Scotland, UK

- 2Consultant Obstetrician, NHS Borders, UK

Received: October 22, 2018; Published: October 26, 2018

*Corresponding author: Yaëlle Chaudy, School of Computing, University of the West of Scotland, UK

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2018.01.000124

Abstract

Clinical Decision Support (CDS) is a growing field and the technology is increasingly used by both clinicians and patients. In maternity care, numerous guidelines exist on risk assessment and proposed care plans during pregnancy and labour. However, as new evidence arise, these guidelines are subject to change. It is time consuming for clinicians to

a. Compile all this information and

b. Keep it up to date.

This paper presents our approach to overcoming these two issues: the SAFER (Safe Assessment Form to Evaluate Risk) maternity system. This CDS system contains rules extracted from current guidelines on maternity care and generates care plans at various stages of gestation based on patient data. The system includes a mobile application and a web interface. The mobile application can be used to visualise care plans and edit patient data. The web interface includes an authoring tool allowing clinicians to edit the logic used to generate the care plans, thus keeping the rules up to date. The tool has been developed for and is currently used by NHS Scotland.

Keywords: Clinical Decision Support Systems; Pregnancy; Maternity; Risk Assessment, Authoring Tool

Abbreviations: CDS: Clinical Decision Support; CDSS: Clinical Decision Support System; SAFER: Safe Assessment Form to Evaluate Risk; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SIGN: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

Introduction

Early identification and management of the risks associated with pregnancy is essential to providing appropriate treatment to pregnant women [1]. In Scotland there are six areas that have been targeted for improved maternal care: post-partum haemorrhage, stillbirth, sepsis, venous thromboembolism, smoking cessation and appropriate induction of labour. Effective identification of maternal risk and its subsequent management is guided by nationally recognised evidence and best practice (e.g. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NICE, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network SIGN). However, with so much evidence and practice guidelines available, health care staff can be overwhelmed by bureaucracy and can miss key clinical factors. Risk assessment is frequently carried out in an ad hoc manner and is not always undertaken.

Clinical Decision Support Systems CDSS

CDSS have been broadly defined as software that provides “clinicians, patients or individuals with knowledge and personspecific or population information, intelligently filtered or presented at appropriate times, to foster better health processes, better individual patient care, and better population health” [2]. Some studies investigating the effectiveness of CDSSs demonstrate their potential to assist with issues raised in clinical practice, decrease the rate of medication errors, increase clinicians’ adherence to guideline- or protocol-based care and improve the overall efficiency and quality of healthcare delivery systems [3- 6]. However, challenges to CDSS development, management and use are complex and sociotechnical in nature, involving people, processes and technology [7]. This complexity has also led to a view that evidence for the role of CDSS in improving safety, quality and efficiency has been mixed. Furthermore, it has been found that simply implementing a CDSS is not sufficient to ensure its use.

Several studies highlight that certain forms of CDSS are turned off or ignored [8]. Poor adoption and use has been attributed to a number of barriers, including but not limited to poor integration of CDSS into clinical workflow, lack of technical support to address hardware and software issues, limited training of clinicians on how to use and apply CDSS when making decisions, context-insensitive alerts and reminders, distrust of clinical guideline-based CDSSs as quality improvement tools, and an overwhelming number of prompts requiring physician attention (“alert fatigue”) [9-10].

While there is significant research on CDSSs generally, there is not an abundance of empirical evidence on the use of CDSS in maternity care. Two key challenges when creating a maternity CDSS are

(i) Compiling multiple guidelines from numerous sources into usable rules and

(ii) Keeping the rules up to date should these guidelines change, or new ones emerge.

SAFER Maternity

The aim of the SAFER project is to provide a risk assessment and risk management system for pregnant women and to engage them at the earliest stage of their pregnancy in the identification and management of pregnancy associated risk. It was originally created as a suite of calculators for maternal risk assessment, held in Excel spreadsheets. In its original format, it has been evaluated by Scottish clinicians in a rural setting. The SAFER form has reduced the use of up to eight risk assessment forms into one and preliminary analysis has shown an improvement in the assessment of venous thromboembolism, foetal growth and post-partum haemorrhage. The original Excel spreadsheet was converted into a web and mobile app solution. The project can be decomposed into three main components:

a) User management: Storage and retrieval of clinical staff and patient details.

b) Rules management: Storage and retrieval of the questions to display in the patient form and the rules for generating care management plans.

c) Care plans management: Storage and retrieval of patient data and generated care plans.

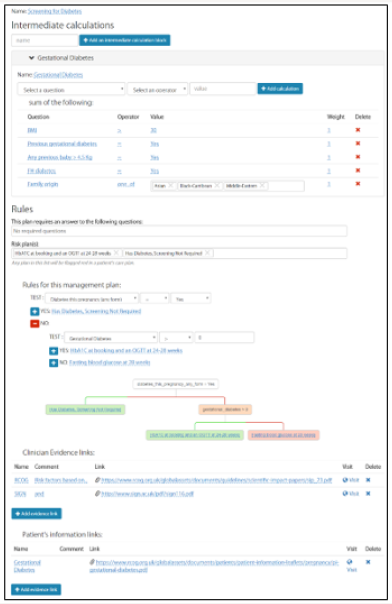

Rules Editor

The rules editor allows a clinician to visually edit the logic behind the generation of care plans for pregnant patients. This can mean modifying the list of questions needed as input and/or changing the way care plans are generated based on the answers. There are some predefined questions that cannot be modified or deleted such as CHI, a unique patient identifier, patient age, height, weight, BMI (calculated from height and weight), EDD (Estimated Due Date), gestation in days. A clinician can add other questions. These new questions can be of two types: numbers (whole or floats) or enums (string selected from a list of possible values). There is no restriction in number. The latest version of the rules contains 53 questions. Questions are grouped in sections such as “Booking appointment”, “Antenatal”, “Labour Ward”. Sections can also be created and deleted. From a patient’s answers to the questions, SAFER generates a number of care plans for the patient. Care plans can be created, deleted and modified and are composed of

(i) A name;

(ii) Intermediate calculations in case some answer needs to be aggregated before being used;

(iii) Rules as a decision tree with a test condition and rules to follow if the condition is true and false;

(iv) A list of evidence links, guidelines justifying the logic behind the care plan’s generation;

(v) A list of information links, for the patient use.

Figure 1 presents the “Screening for diabetes” care plan view in the editor. The latest version of the rules have 13 care plans: Folic Acid, Aspirin, Screening for diabetes, Smoking cessation, Iron treatment, Growth assessment, Antenatal Heparin Prophylaxis, Inpatient Heparin Prophylaxis, Postnatal Heparin Prophylaxis, PPH prevention, Pyrexia, Intrapartum Group B strep Rx and Bladder after delivery.

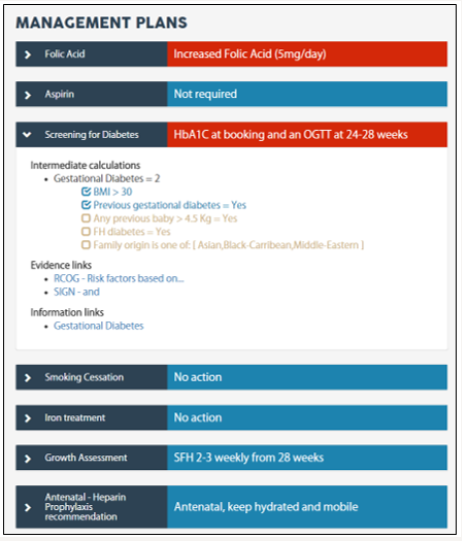

Patient View

Once a set of rules has been created and published, it can be used in the patient view to generate her care plans. The patient view is available in both the web interface and the mobile application for clinicians and patients. Clinicians can update all the information displayed while patients have a read-only access. The patient view is divided in two parts. First, the sections specified in the editor as shown as tabs displaying their questions as dropdown options or number inputs. Second, the care plans are shown as accordion panes. Default plans are shown in blue and risk in red for quick identification of action needed. For more information on the care plan, a user (clinician or patient) can click on the accordion pane. Inside, it displays the detail of the intermediate calculations used; every risk factor is listed and a ticked/unticked box specifies whether the statement is true for the patient. Evidence and information links are also shown. Figure 2 shows some of the care plans for Mary Smith who has a BMI over 30 and a history of gestational diabetes. The “Screening for diabetes” pane is open.

Conclusion

This paper presented a CDSS: SAFER maternity. This project aims to improve early identification and management of risks associated with pregnancy. SAFER maternity is aimed at both clinicians and patients and is to be used throughout pregnancy and labour. The system also caters for changes in the pregnancy care guidelines. This paper introduced a rules editor that can be used by clinicians with special privileges to amend the rules used to generate care plans. It also presented the patient view of questions and care plans. Further work will include piloting the tool for usability and usefulness evaluation as well as collecting data for a quantitative evaluation of its effect on pregnancy and positive outcome improvement in crucial areas such as post-partum haemorrhage, stillbirth, sepsis, venous thromboembolism, smoking cessation and appropriate induction of labour.

References

- National Institute for Health Care Excellence (2008) Antenatal Care for Uncomplicated Pregnancies. Nice Clinical Guidelines. London.

- Osheroff JA, Teich JM, Middleton B, Steen EB, Wright, et al. (2017) A Roadmap for National Action on Clinical Decision Support. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 14(2): 141-145.

- Bright TJ, Wong A, Dhurjati R, Bristow E, Bastian, et al. (2012) Effect of Clinical Decision Support Systems Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine 157(1): 29-43.

- Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica, et al. (2006) Systematic Review: Impact of Health Information Technology on Quality, Efficiency and Costs of Medical Care. Annals of Internal Medicine 144(10): 742- 752.

- Holbrook A, Thabane L, Keshavjee K, Dolovich L, Bernstein B, et al. (2009) Individualized Electronic Decision Support and Reminders to Improve Diabetes Care in the Community: Compete II Randomized Trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal 181(1-2): 37-44.

- Sequist TD, Gandhi TK, Karson AS, Fiskio JM, Bugbee D, et al. (2015) A Randomized Trial of Electronic Clinical Reminders to Improve Quality of Care for Diabetes and Coronary Artery Disease. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 12(4): 431-437.

- Ash JS, Sittig DF, Mcmullen CK, Wright A (2015) Multiple Perspectives on Clinical Decision Support: A Qualitative Study of Fifteen Clinical and Vendor Organizations. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 15(1): 35.

- Shah NR, Seger AC, Seger DC, Fiskio JM, Kuperman GJ, et al. (2006) Improving Acceptance of Computerized Prescribing Alerts in Ambulatory Care. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 13(1): 5-11.

- Moxey A, Robertson J, Newby D, Hains I, Williamson M, et al. (2010) Computerized Clinical Decision Support for Prescribing: Provision Does Not Guarantee Uptake. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 17(1): 25-33.

- Kesselheim AS, Cresswell K, Phansalkar S, Bates, Sheikh A (2011) Clinical Decision Support Systems Could Be Modified to Reduce ‘Alert Fatigue’ while Still Minimizing the Risk of Litigation. Health Affairs 30(12): 2310- 2317.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...