Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-4722

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-4722)

11 Cases of H-Type Tracheoesophageal Fistula: How Diagnosis and Treatment May Be Improved Volume 4 - Issue 1

N Laizer1*, U Mehlig1, P Amrhein2, O Diez1, M Sidler1, T Rabanus-Wallace1, R Staubach1, PMüller-Abt3 and S Loff1

- *1Department of Pediatric Surgery, Olgahospital, Klinikum Stuttgart, Germany

- 2Department of ENT, Olgahospital, Klinikum Stuttgart, Germany

- 3Department of Pediatric Radiology, Olgahospital, Klinikum Stuttgart, Germany

Received: January 04, 2023 Published: January 09, 2023

Corresponding author: N Laizer, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Olgahospital, Klinikum Stuttgart, Germany

DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2023.04.000179

Abstract

Congenital H- type tracheo-esophageal Fistulas (TOF) or esophageal atresia type IV (Vogt classification 1929) are rare congenital malformations. 1:50 000- 1:100 000 children are born with H-TOF [1]. Late diagnosis is typical and usually requires intensive diagnostics. The rareness of this malformation as well as the unspecific symptoms are the main reasons for late diagnosis. During the years 2009-2022, 11 patients with H-TOF were treated in our clinic. In this paper all cases will be presented, and diagnostics and treatment will be discussed. The aim of this study is to improve diagnosis and to minimize complications, such as paralysis of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Keywords: H- type tracheo-esophageal fistulas; esophagogram; tracheobronchoscopy; diagnosis

Introduction

One of the most common classification systems of esophageal atresia’s is the Vogt classification. The Vogt classification divides the esophageal atresia’s in types I, II, IIIa, b, c and IV. Type IV is characterized by an H-type fistula (H-TOF) between the esophagus and the trachea without atresia. H-TOFs account for 4-5% of all esophageal atresia’s [1,2] with male and female being equally affected. Transtracheal surgical repair of an H-TOF was first performed in 1938 on a 6-year-old girl [3,4]. In 1948, Haight reported an H-TOF repair through a thoracic approach. In 1958, Miller reported the first cervical access repair of H-TOF. One of the greatest risks when treating H-TOF surgically is injury of the right recurrent nerve causing paralysis of the vocal cords, though the paralysis is often reversible [1,5]. Refistulas are rare. H-TOF may present with choking during feeding sessions, coughing attacks or desaturation while drinking, as well as recurrent respiratory infections. The symptoms are sometimes misguiding, which may lead to delayed diagnosis. Thus, the time of diagnosis varies from infancy to adulthood [6-11]. Diagnostic measures comprise an esophagogram with a contrast agent or tracheobronchoscopy. Due to the oblique course of the fistula- from esophageal caudal to tracheal cranial imaging with a contrast medium is difficult. Several studies have shown that imaging must occasionally be performed multiple times to diagnose an H-TOF. This poses additional risks of aspirations and radiation exposure. Tracheobronchoscopy, in contrast is a highly reliable diagnostic tool that identifies H-TOF in infants and newborns. Furthermore, using tracheobronchoscopy the fistula can be marked with a wire that helps a surgeon to identify the fistula during subsequent open repair surgery [10,11].

Patients and Methods

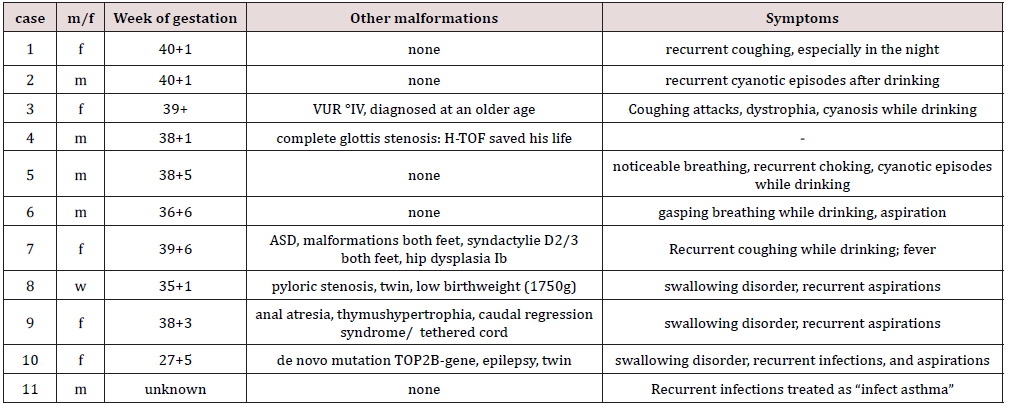

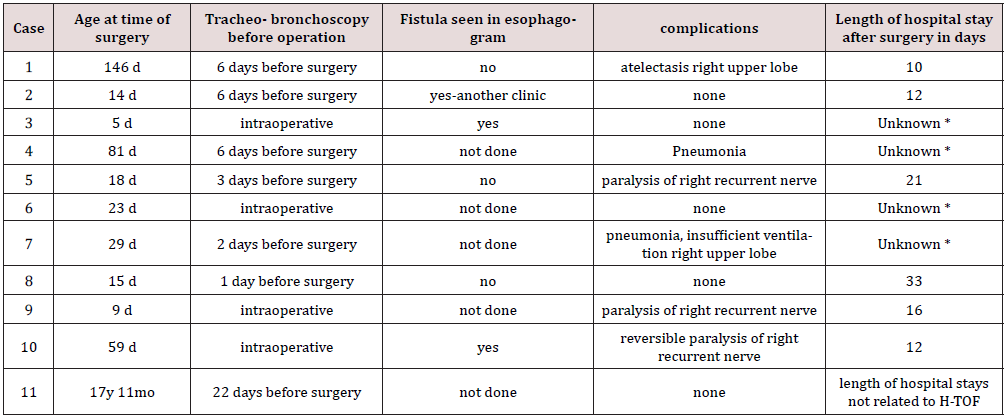

From 2009-2022 11 patients with H-TOF were treated in the department of pediatric surgery in Olgahospital Stuttgart. Patient variables including gender, week of pregnancy at birth, birthweight, other malformations, symptoms, success of esophagogram, age at time of surgical repair, age at tracheobronchoscopy, complications, length of stay in hospital after surgical repair are given in Tables 1 & 2. Of the 11 patients 9 were born on time. Two were delivered prematurely in 35+1 and 27+5 gestational week respectively. Three of the patients had other malformations- one was born with a gene defect, the other had a complete laryngeal atresia. One of the patients was born with various malformations of both feet as well as an ASD. One patient had an anal atresia.

*Patient was transferred back to their home hospitals before discharge.

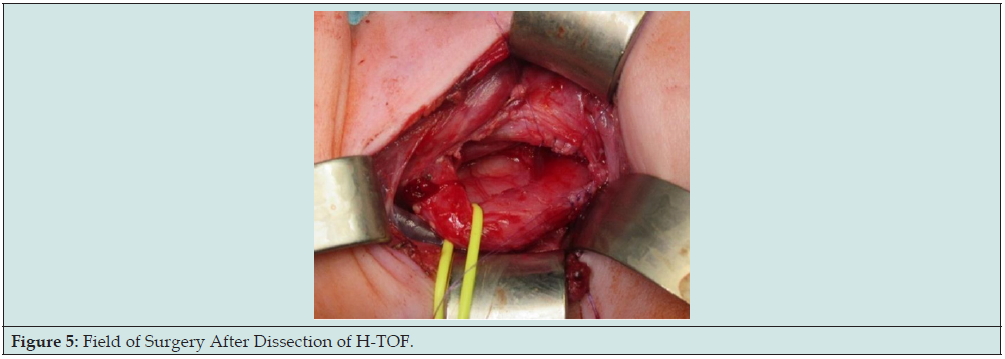

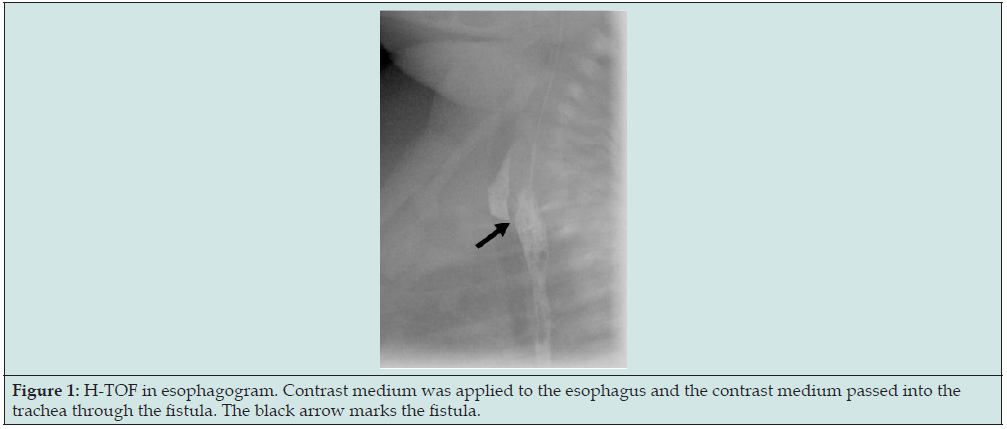

Of the 11 patients, two were born in Stuttgart. All the other patients were transferred from other hospitals. One patient had been diagnosed with H-TOF at the clinic in which the patient was born. All other patients were diagnosed in domo with H-TOF. One patient was diagnosed immediately after birth as he had a complete larynx stenosis and would not have been able to survive without H-TOF. H-TOF was life- saving in this case. In 6 of these patients a single esophagogram was performed, which diagnosed H-TOF in 3 cases. In all patients tracheobronchoscopy was performed and the fistula was identified in all cases (Figures 1-3). One patient was 17 years old when H-TOF was diagnosed. He had a long history of recurrent airway Infections, which was misdiagnosed as infectious asthma. At the age of 17 he was treated for lymphoma and suffered from a pneumomediastinum. Thus, a tracheobronchoscopy was performed, which revealed a large H-type Fistula. In three cases surgical repair of H-TOF was performed under the same anesthesia induced for the tracheobronchoscopy.

Figure 1:H-TOF in esophagogram. Contrast medium was applied to the esophagus and the contrast medium passed into the trachea through the fistula. The black arrow marks the fistula.

Figure 2: Esophagobronchial fistula (black arrow). Left bronchus (white arrow) and right bronchus (blue arrow).

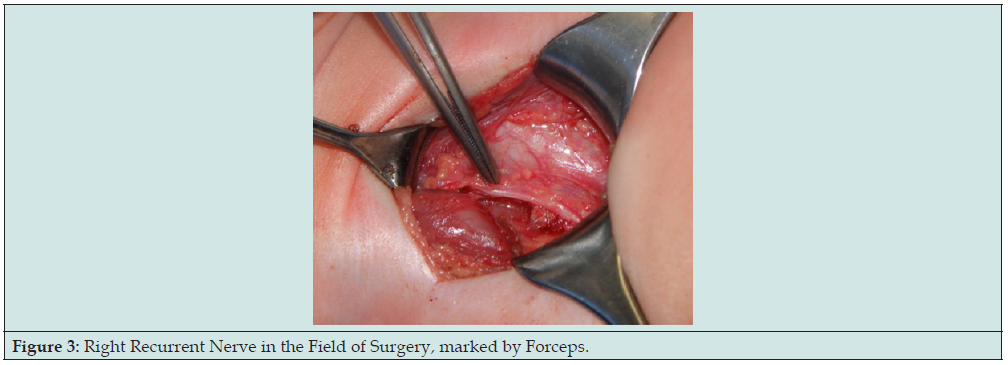

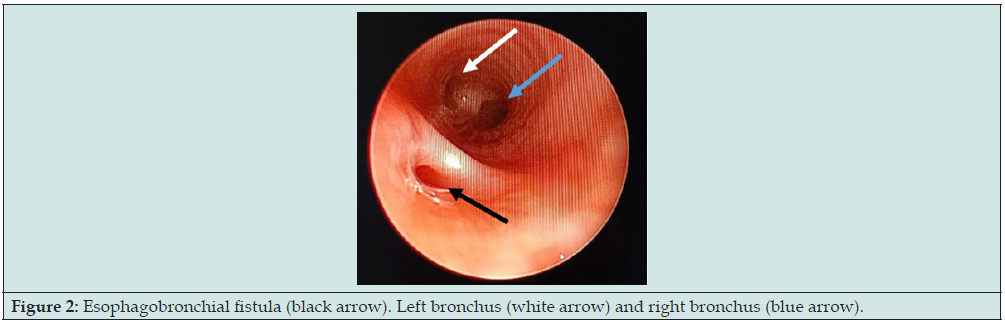

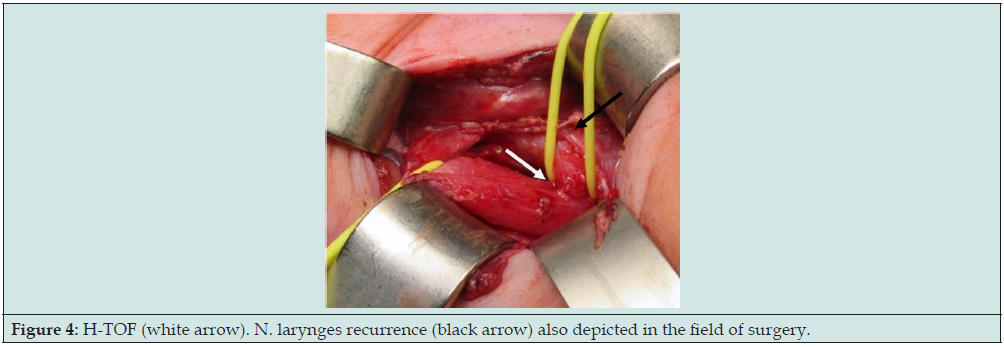

Surgical repair was usually performed within 6 days following diagnosis, with one exception- the 17-year-old cancer patient. The repair was in all cases carried out through a right cervical access. In all cases the right recurrent nerve was identified, such that maximum care could be taken to avoid damage. In infants the right recurrent nerve runs more distal to the esophagus compared with adults and therefore typically leads directly through the field of surgery, close to the esophagobronchial fistula (Figures 4 & 5). Furthermore, preparation must also be done very carefully in order not to harm the left recurrent nerve by accident. In only one of the patients a gastroscopy had to be performed 19 months after primary surgery, when the patient presented with a stenosis. This patient underwent gastroscopy and dilatation once and has not suffered any problems related to the condition to date. Despite all caution, three patients suffered paralysis of the right recurrent nerve. One patient was lost on follow- up, the second recovered spontaneously, the third is awaiting its checkup endoscopy. Three patients suffered from pneumonia postoperatively. It is unknown whether pneumonia was a consequence of the operation or a complication of the fistula itself.

Figure 4: H-TOF (white arrow). N. larynges recurrence (black arrow) also depicted in the field of surgery.

Discussion

Key ongoing discussions on H-TOF concern which diagnostic methods are necessary, how to diagnose H-TOF as fast as possible, what the various risks of the different methods are and how best to proceed when H- TOF is diagnosed [6,7,10,12]. In this investigation, 6 out of 11 patients had an esophagogram, which was successful in 3 cases. Not more than one esophagogram was performed on each patient. If an esophagogram was done earlier on in another clinic without success, the investigation was not repeated. The sensitivity of esophagogram was low as it was also described in many other studies before [1,6,13,14,16]. The esophagogram allows to rule out differential diagnosis such as esophagus stenoses, gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal diverticula or swallowing disorders. These differential diagnoses can´t be seen in a tracheobronchoscopy. In order not to miss differential diagnoses and at the same time not to prolong diagnosis one should perform a single esophagogram when H-TOF is suspected.

A tracheobronchoscopy was performed in all patients and was diagnostic in all. Thus, the tracheobronchoscopy is a very sensitive diagnostic tool for H-TOF. Other advantages of a tracheobronchoscopy compared to an esophagogram are a lesser risk for aspiration and no radiation. Also, there are some rare differential diagnoses which can be identified or ruled out by tracheobronchoscopy only. Namely these are laryngeal cleft, subglottic hemangioma, or laryngeal stenosis [15, 17-21]. The disadvantage of a tracheobronchoscopy of course is, that the child needs full anesthesia. Based on the known success rate of tracheobronchoscopy for H-TOF diagnosis compared with esophagogram diagnosis observed in this study one could argue that on urgent suspicion of H- TOF, one should first resort to tracheobronchoscopy and to an esophagogram second and only if further investigation of a negative tracheobronchoscopy is required [6,10,12].

In cases of unspecific symptoms, esophagogram should still be the first diagnostic performed. In four cases surgical repair could be performed in the same anesthesia as the initial tracheobronchoscopy. In two of these patients, H-TOF was suspected as a result of a prior esophagogram. The “single-anesthesia pathway” requires a team of highly specialized ENT Doctors, pediatric surgeons, anesthesiologists, and specialized equipment. For this reason, diagnosis and repair can rarely be performed in one session only. However, increasing the proportion of patients who can be treated and diagnosed under the same anesthesia is desirable, because the fistula only needs to be depicted by the ENT doctors once, which ultimately entails less manipulation and a lower risk of injury. The therapy goal can thus be achieved faster. Studies described a vocal cord paralysis in up to 50% of operated H-TOF. In this investigation only 3 of 11 presented with a right sided vocal cord paralysis after the surgery. This comparatively favorable result may reflect the benefits of placing particular focus on preparing the right recurrent nerve when repairing for H-TOF surgery. Even if in many cases the paralysis is temporary and not permanent.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Approval

None.

References

- Ahmed H Al-Salem, Mohammed Al Mohaidly, Hussah M H Al-Buainain, Saud Al-Jadaan, Enaem Raboei (2016) Congenital H-type tracheoesophageal fistula: a national multicenter study. Pedaitr Surg Int 32(5): 487-491.

- Kiarash Taghavi, Sharman P Tan Tanny, Alisa Hawley, Jo-Anne Brooks, John M Hutson, et al. (2021) H-type congenital tracheoesophageal fistula: Insights from 70 years of The Royal Children´s Hospital experience. J Pediatr Surg 56(4): 686-691.

- Imperatori CJ (1939) Congenital tracheo-esophageal fistula without atresia of the esophagus. Arch Otolaryngol 30: 352.

- Laquet A and Fransen G (1974) Isolated Tracheoesophageal Fistula in: Diseases of the Esophagus. Handbuch der inneren Medizin (verdauungsorgane), Springer, Berlin 3: pp.639-624.

- Fung SW, Lapidus-Krol E, Chiang M, Fallon EM, Haliburton B, et al. (2019) Vocal cord dysfunction following esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula (EA/TEF) repair. J Pediatr Surg 54(8): 1551-1556.

- Spataru RI, Iozsa DA, Lupusoru MOD, Serban D, Cirstoveanu C (2021) Practical safety in the diagnosis and treatment of congenital isolated tracheoesophageal fistula. Exp Ther Med 21(5): 537.

- Lee SYS, Hamouda ESM (2018) H-type tracheoesophageal fistula diagnosed on video fluoroscopy swallowing study. BMJ Case Rep 11(1): bcr2018227794.

- Benjamin B, Pham T (1991) Diagnosis of H-type tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg 26(6): 667-671.

- Stack M, Westmoreland T (2020) Adolescent with VACTERL Association Presents with Recurrent Pneumonia. Cureus 12(9): e10365.

- Tiwari C, Nagdeve N, Saoji R, Nama N, Khan MA (2021) Congenital H-type tracheo-oesophageal fistula: An institutional review of a 10-year period. J Mother Child 24(4): 2-8.

- Biechlin A, Delattre A, Fayoux P (2008) Isolated congenital tracheoesophageal fistula. Retrospective analysis of 8 cases and review of the literature. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 129(3): 147-152.

- Cuestas G, Rodríguez V, Millán C, Bellia Munzón P, Bellia Munzón G (2020) H-type tracheoesophageal fistula in the neonatal period: Difficulties in diagnosis and different treatment approaches. A case series. Arch Argent Pediatr 118(1): 56-60.

- Laffan EE, Daneman A, Ein SH, Kerrigan D, Manson DE (2006) Tracheoesophageal fistula without esophageal atresia: are pull-back tube esophagograms needed for diagnosis? Pediatr Radiol 36(11): 1141-1147.

- Karnak I, Senocak ME, Hiçsönmez A, Büyükpamukçu N (1997) The diagnosis and treatment of H-type tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg 32(12): 1670-1674.

- de Alarcón A, Osborn AJ, Tabangin ME, Cohen AP, Hart CK, et al. (2015) Laryngotracheal Cleft Repair in Children with Complex Airway Anomalies. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 141(9): 828-833.

- Kirk JM, Dicks-Mireaux C (1989) Difficulties in diagnosis of congenital H-type tracheo-oesophageal fistulae. Clin Radiol 40(2): 150-153.

- Ahmad SM, Soliman AM (2007) Congenital anomalies of the larynx. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 40(1): 177-191.

- Corbally MT, Fitzgerald RJ, Guiney EJ, Ward D, Blayney A (1993) Laryngo-tracheo-oesophageal cleft: a plea for early diagnosis. Eur J Pediatr Surg 3(4): 241-243.

- Leboulanger N, Garabédian EN (2011) Laryngo-tracheo-oesophageal clefts. Orphanet J Rare Dis 6: 81.

- Roth B, Rose KG, Benz-Bohm G, Günther H (1983) Laryngo-tracheo-oesophageal cleft. Clinical features, diagnosis and therapy. Eur J Pediatr 140(1): 41-46.

- Sundar B, Guiney EJ, O Donnell B (1975) Congential H-type tracheo-oesophageal fistula. Arch Dis Child 50(11): 862-863.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...