Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1709

Case Report(ISSN: 2641-1709)

Spontaneous Pneumothorax and Cavitated Lesions as First Manifestation of Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma to Ovary and Peritoneum in Young Patient? Volume 2 - Issue 1

Ricardo Bruges1, Marcela Bermúdez2* and Pedro Sanabria2

- 1Head of Department of Medical Oncology, Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia, Universidad El Bosque, Associate Professor of Internal Medicine Universidad Javeriana Centro Oncológico Javeriano, Colombia, USA

- 2Oncology Fellow in training, Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia, Universidad El Bosque, Colombia, USA

Received:April 29, 2019; Published:May 08, 2019

Corresponding author: Marcela Bermúdez, Oncology Fellow in training, Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia, Universidad El Bosque, Colombia, USA

DOI: 10.32474/SJO.2019.02.000130

Abstract

We present the report of a case of lung cancer of atypical manifestation with important challenges in its diagnosis in a young woman who came in with pneumothorax tension, cavitated lung lesions, ovarian, hepatic and peritoneal masses and a biopsy compatible with pulmonary adenocarcinoma, whose initial approach raised the differential diagnosis of a tumor of gynecological origin. A brief literature review was conducted.

Keywords: Pneumothorax; Pulmonary Cavitation; Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma; Ovarian Metastasis; TTF1

Introduction

A 28-year-old woman who consulted the emergency department of the National Cancer Institute (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología) for a 7-month history of asthenia, adinamia, progressive dyspnea, low cough, loss of 17 kilograms of weight and the appearance of a painful mass at the level of the iliac fossa and right flank. Initially studied as an outpatient with presumptive diagnosis of granulomatous disease with negative serial baciloscopy and chest x-ray showing right atelectasis + right pneumothorax. In the tomography multiple solid nodules some with hypodense center involving both pulmonary fields, caverns of thickened walls in both apices, posterior segments of the lower lobes and upper segments of the lower lobes. In the abdominal tomography there is presence of mass surrounding uterus of 185*100*85 mm of density of soft tissues, which takes the contrast IV and cystic area of 85 mm in its right aspect of probable ovarian origin and hepatic compromise with apparent peritoneal sowings. Positive tumor markers AFP 1.2, ACE 392, CA 125 257. A right thoracostomy, fibro bronchoscopy with cultures for M. negative tuberculosis and biopsy of pelvic mass that reported lesion characterized by cords and neuroglandular formation of epithelioid cells of neoplastic aspect with a marked desmoplasic response were initially performed. For which the diagnosis of metastatic ovarian cancer to lung, liver and peritoneum is made and send to initiate management.

Case Report

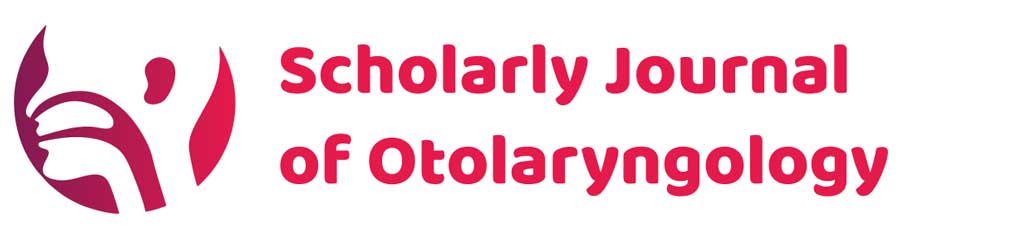

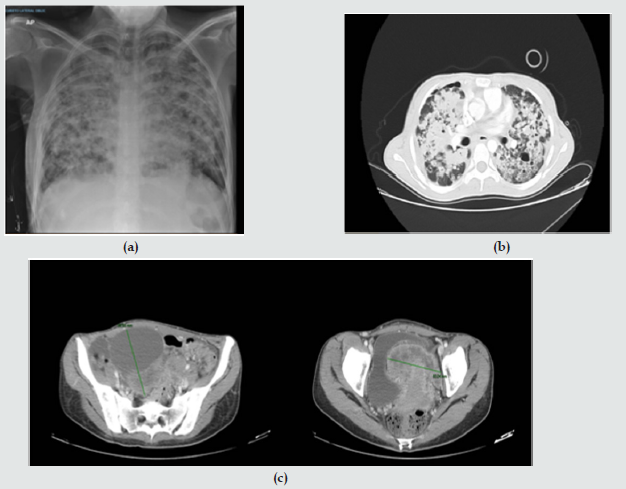

Upon admission to the institution, pulmonary thromboembolism is ruled out and extensive pulmonary parenchymatous involvement (Figure 1(a)) is confirmed by nodular areas, most of them with central cavitation and frosted glass halo, which are accompanied by paramilitary consolidations, making it necessary to consider neoplastic metastatic involvement with cavitation, less likely infectious (angioinvasive aspergillosis). At abdominal level, extensive infiltrative involvement of the peritoneum, hepatic subcapsular with extension to the parenchyma in segment 6, gastrohepatic ligament, transverse mesocolon, descending mesocolon. Heterogeneous bilateral adnexal masses of neoplastic aspect (Figure 1(b&c)). Scarce ascites. We reviewed pathology material of ovarian mass biopsy with report of adenocarcinoma with reactive immunopurified for CK7, TTF1 and negative for GATA 3, WT1, RE, CDX2, PAX 8 and CK20, we added NAPSIN which was positive, confirming lung metastatic origin (Figure 2(a&b)). The new fibro bronchoscopy with biopsy had immunohistochemistry that showed reactivity in tumor cells for TTF-1 and Napsin with absence of reactivity for p40, RE and RP. Compatible with compromise by non-small cell carcinoma, favors acinar pattern primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Less than 10% of all lung carcinomas debut with radiological cavitations, considered secondary to tumor necrosis by ischemia and/or bronchial obstruction [1]. Tokito et al. presented a cohort of lung cancer patients, with an incidence of cavitated lesions of 5.5% meanwhile in the Sing series this report is much higher near 9.6%. In both cohorts it was more frequent to find cavitations in men, over 60 years old, ex-smokers and with squamous cell histology [2].

Figure 1: (a) Chest X ray; (b) Axial computed tomography with extensive pulmonary parenchymatous involvement. (c) Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with mass surrounding uterus.

Figure 2: (b) Immunohistochemistry of Napsine A in lung tissue; (b) Immunohistochemistry of TTF1 in ovarian tissue.

a greater extent induced by oncologic management are infection and hemoptysis, very infrequently, the presence of spontaneous pneumothorax which is estimated between 0.03 and 0.05% of primary lung cancer with a poor prognosis [3,4]. Among 1200 patients with spontaneous pneumothorax between 1970 and 2007, 37 (3%) had lung cancer. In all patients, the pneumothorax occurred on the same side of the carcinoma. The main cause of spontaneous pneumothorax was rupture of a necrotic tumor nodule or necrosis of subpleural metastases (21 ptes)., As well as the communication between the bronchus and the pleural cavity, producing a bronchopleural fistula that results in pneumothorax [5]. Spontaneous pneumothorax in the context of lung cancer occurs in 75% of cases as an initial manifestation and the remaining 25% during the course of the disease in patients with the known diagnosis, sometimes after the onset of management [6]. In this case, the first clinical manifestation of oncological disease was the presence of dyspnea secondary to spontaneous pneumothorax, infectious causes were ruled out and required surgical intervention with subsequent need for high oxygen flow. The main sites of lung cancer metastasis are pleura, brain, bone and liver. Ovarian metastases are rare, accounting for 5% of all ovarian cancers. The main tumors that metastasize to the ovary are from the gastrointestinal tract: colon and gastric, or originated in the breast. Lung cancer alone is the cause of these metastases by 0.3% [7]. The metastases of an adenocarcinoma of the lung are difficult to distinguish from a primary carcinoma of the ovary. Although there is no specific lung marker, TTF-1 can be used to discriminate between primary pulmonary and ovarian. TTF-1 is positive in approximately 63% of lung cancers [8]. Irving and Young reported 32 cases of metastatic to ovarian lung carcinoma in women aged 26 to 76. A history of lung carcinoma was documented in 53% of cases (17 out of 32), with detection of ovarian involvement at an interval of one year. In 10 cases (31%) ovary and lung occurred synchronously, in 5 (16%) ovarian tumors were detected 26 months before lung injury. The most frequent histologic subtype was small cell carcinoma 44%, adenocarcinoma in 34% and 16% in large cell carcinoma in 16% of patients. One third had bilateral presentation and the most frequent morphological characteristics were: multinodular growth, necrosis, lymphovascular invasion with rare involvement of the ovarian surface [9]. The management decision in this case was made considering the presence of pulmonary visceral crisis, the patient’s age, her ECOG and the high risk of rapidly deteriorating. Chemotherapy with palliative intention was started with carboplatin paclitaxel with a good clinical response in the two initial cycles, with which the requirement of supplementary oxygen and control of dyspnea was reduced. 40 days later, the patient was admitted with subite dyspnea of 3 days of evolution. with chest x-ray (Figure 3) that evidences left pneumothorax, ventilatory failure and dies despite rescue procedure.

Conclusion

Patients with cavitated tumors develop serious complications during or after chemotherapy or concomitance such as infection or massive hemoptysis. There are no reports of safety and efficacy of the use of chemotherapy in patients with advanced lung cancer with cavitated lesions. Some retrospective reports that have evaluated toxicity in this group of patients in the a 9% study developed hemoptysis, considering it as acceptable toxicity for this group of patients. Sandler et al reported that 30% of patients treated with carboplatin+paclitaxel+bevacizumab presented hemoptysis vs 6% of those without cavitations. In our case, taxane and platinumbased chemotherapy were initiated while obtaining studies of EGFR, ALK, Ros 1 and PDL1 to optimize management, with the initial cycles the palliation objective was achieved. However, the subsequent occurrence of pneumothorax is a possible consequence of the effect of cytotoxic treatment on existing lung lesions. It is not clear from the literature what would be the safest scheme, dose or frequency for this population to avoid the development of this type of complications. It is necessary to increase the reporting of these cases in order to try to elucidate their management.

References

- Fraser RG, Muller NL, Colman NC (1999) Pulmonary Carcinoma. In: Diagnosis of disease of the chest. (4th edn), Philadelphia: WB Saunders, pp. 1148-1149.

- Singh N, Mootha VK, Madan K (2013) Tumor cavitation among lung cancer patients receiving first-line chemotherapy at a tertiary care centre in India: association with histology and overall survival. Med Oncol 30(3): 602.

- Baumann MH, Noppen M (2004) Pneumothorax. Respirology 9(2): 157-164.

- Sahn SA, Heffner JE (2000) Spontaneous Pneumothorax. N Engl J Med 342(12): 868-74.

- Vencevičius V, Cicėnas S (2009) Spontaneous pneumothorax as a first sign of pulmonary carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 7(1): 57.

- OConnor BM, Ziegler P, Spaulding MB (1992) Spontaneous pneumothorax in small cell lung cancer. Chest 102(2): 628-629.

- Irving J, Young R (2005) Lung carcinoma metastatic to the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases emphasizing their morphologic spectrum and problems in differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 29(8): 997-1006.

- Loreto C Di, Lauro D, Puglisi F, Damante G, Fabbro D, et al. (1997) Immunocytochemical expression of tissue specific transcription factor-1 in lung carcinoma. J Clin Pathol 50: 30-32.

- Sandler AB, Schiller JH, Gray R, Dimery I, Brahmer J, et al. Retrospective Evaluation of the Clinical and Radiographic Risk Factors Associated with Severe Pulmonary Hemorrhage in First-Line Advanced, Unresectable Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel Plus Bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol 27(9): 1405-1412.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...