Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Research ArticleOpen Access

Pattern of Congenital Ocular Anomalies among Children Seen at a West African Tertiary Eye Care Centre Volume 2 - Issue 4

Kareem Olatunbosun Musa1*, Sefinat Abiola Agboola2, Olapeju Ajoke Sam-Oyerinde2, Salimot Tolani Salako2, Chinwendu Nwanyieze Kuku2, Chinyei Joan Uzoma2

- 1Department of Ophthalmology (Guinness Eye Centre), Lagos University Teaching Hospital/ College of Medicine of the University of Lagos

- 2Department of Ophthalmology (Guinness Eye Centre), Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi-Araba, Lagos

Received:December 21, 2019; Published:January 10, 2020

Corresponding author:Department of Ophthalmology (Guinness Eye Centre), Lagos University Teaching Hospital/ College of Medicine of the University of Lagos, Idi-Araba, Lagos

DOI: 10.32474/TOOAJ.2020.02.000144

Abstract

Purpose: To describe the pattern of presentation of congenital ocular anomalies among children seen at Department of Ophthalmology (Guinness Eye Centre), Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria.

Methods: A retrospective chart review of children below the age of 16 years who were diagnosed of any type of congenital ocular anomaly at the Pediatric Ophthalmology Clinic of Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) between January, 2012 and December, 2018 was done. Information concerning age at presentation, gender, affected eye(s), visual acuity and type of congenital anomaly were retrieved from the case files.

Results: Seven hundred and forty-five eyes of 470 patients with congenital anomalies which constituted 13.6% of all the new pediatric ophthalmic consultations were studied. Two hundred and seventy-five (58.5%) children had bilateral ocular involvement while 262 (55.7%) presented within the first year of life. The median age was 0.92 years with an interquartile range of 2.67 years. There were 255 (54.5%) males with a male to female ratio of 1.2:1. Congenital cataract was the most common congenital ocular anomaly documented in 224 (30.1%) eyes of 133 patients. This was followed by congenital squint (131 eyes, 17.6%), congenital glaucoma (91 eyes, 12.2%) and corneal opacity (52 eyes, 7.0%). Overall, cataract, squint, glaucoma, corneal opacity, nasolacrimal duct obstruction and ptosis accounted for 79.0% of the congenital ocular anomalies documented in this study.

Conclusion: Congenital ocular anomalies accounted for 13.6% of Paediatric ophthalmic consultations in this study. Congenital cataract, squint, glaucoma, corneal opacity, nasolacrimal duct obstruction and ptosis were the most common congenital ocular anomalies observed.

Keywords: Congenital Ocular Anomalies; Children; West African; Tertiary Eye Care

Introduction

Congenital anomalies are structural or functional anomalies that occur during intrauterine life and can be identified prenatally, at birth, or sometimes may only be detected later in infancy [1]. Congenital ocular anomalies contribute significantly to childhood visual impairment and blindness [2,3]. Some of these anomalies have only cosmetic significance while others cause no symptoms and may be an incidental finding [3]. They may occur in isolation, in combination, or as part of a systemic malformation syndrome [4]. The aetiology of congenital ocular anomalies may be genetic, environmental or more commonly, idiopathic [4]. Globally, the pattern of congenital ocular anomalies varies from region to region. Congenital cataract and glaucoma had been reported to be the most common anomalies in developing countries [2-8] while anophthalmos, microphthalmos and coloboma are predominant in developed nations [9]. Severe visual loss arising from some of these ocular anomalies in early childhood could adversely affect their development, mobility, education, social life and employment opportunities [2]. In addition, accompanying parents and/or care givers lose valuable time and resources seeking interventions for these children. It is therefore imperative that they are better characterized in order to aid appropriate intervention strategy and resource allocation. Therefore, this study sought to describe the pattern of congenital ocular anomalies among children seen at Guinness Eye Centre, Lagos University Teaching Hospital with a view to determining the most common anomalies in this Centre.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of the case files of children below the age of 16 years who were diagnosed of any type of congenital ocular anomaly at the Paediatric Ophthalmology Clinic of Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) between January, 2012 and December, 2018 was done. Information concerning age at presentation, gender, affected eye(s), visual acuity and type of congenital anomaly were retrieved from the case files. Ethical approval was obtained from Health Research Ethics Committee of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (Approval Number: ADM/ DCST/HREC/APP/1915). Data obtained was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY). Data was presented in tables. The quantitative visual acuity was classified into normal vision, visual impairment and blindness using the International Classification of Disease, 11th revision (ICD-11) as much as possible [10]. Normality of numerical variables was ascertained using Shapiro-Wilk test. The association between categorical variables was analyzed using chi-square test and Fishers exact was used as appropriate. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

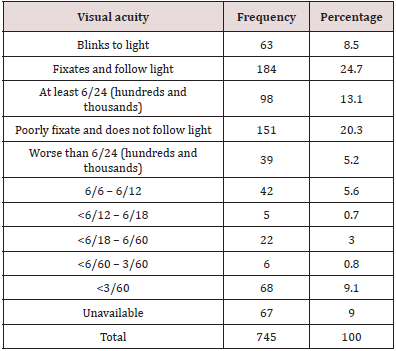

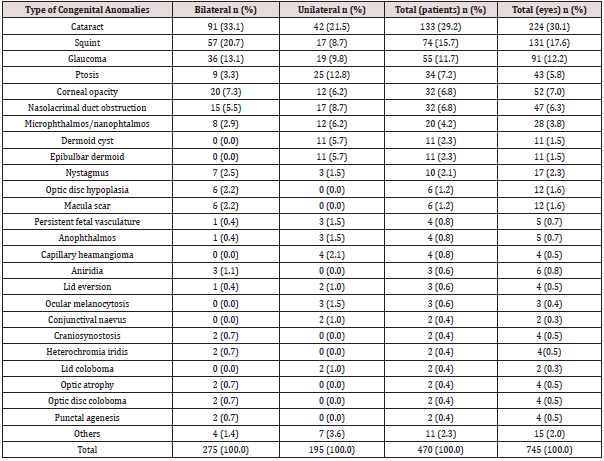

Seven hundred and forty-five eyes of 470 patients with congenital anomalies were studied. This accounted for 13.6% of all the new Paediatric ophthalmic consultations during the years under review. Two hundred and seventy-five (58.5%) children had bilateral ocular involvement while ocular affectation was unilateral in 195 (41.5%) children (Table 1). Only 43 (9.1%) presented within the first month of life while 262 (55.7%) presented within the first year of life. Overall, majority (87.4%) presented within the first five years of life as shown in Table 1. The youngest patient at presentation was a nine-hour old neonate with bilateral congenital lid eversion while the oldest patient was a 15 year old teenager with bilateral congenital cataract. The median age was 0.92 years with an interquartile range of 2.67 years (p <0.001 for Shapiro- Wilk test). There were 255 (54.5%) males with a male to female ratio of 1.2:1. There was no statistically significant association between gender and age at presentation (p = 0.37). Table 2 shows the presenting visual acuity (VA) distribution in the affected eyes of the patients. They were documented using qualitative assessment of visual behavior of the patients, hundreds and thousands as well as Snellen chart. Sixty-eight (9.1%) eyes were blind (VA < 3/60), 67 (9.0%) had moderate/severe visual impairment (VA <6/18 to 3/60) while 151 (20.3%) had poor light fixation and did not follow light. Thirty-four (50.0%) out of the 68 blind eyes as well as 32 (47.8%) out of the 67 eyes with moderate/severe visual impairment were due to congenital cataract making it the most blinding and visually impairing congenital ocular anomaly in this study Congenital cataract was the most common congenital ocular anomaly documented in 224 (30.1%) eyes of 133 patients (Table 3). It was also the most common bilateral (91 patients, 33.1%) as well as unilateral (42 patients, 21.5%) congenital ocular anomaly. This was followed by congenital squint (131 eyes, 17.6%), congenital glaucoma (91 eyes, 12.2%) and corneal opacity (52 eyes, 7.0%). Overall, cataract, squint, glaucoma, corneal opacity, nasolacrimal duct obstruction and ptosis accounted for 79.0% of the congenital ocular anomalies documented in this study. The most common type of congenital squint was congenital esotropia (119, 90.8%) while congenital exotropia was documented in 12 (9.2%) eyes. The causes of congenital corneal opacity were Peter’s anomaly (16, 30.8%); sclerocornea (12, 23.1%); congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (9, 17.3%); anterior segment dysgenesis (2, 3.8%); others (6, 11.5%) and undocumented (7, 13.5%).

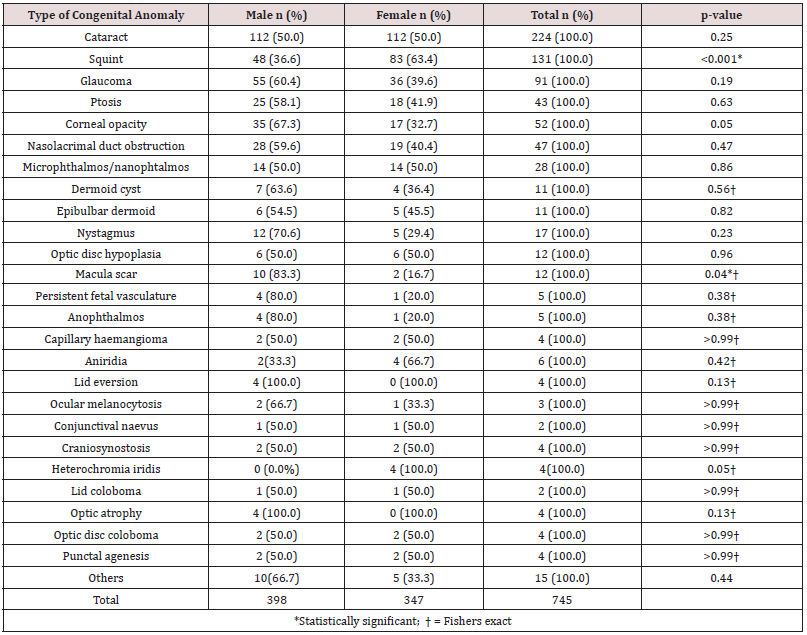

Table 4 shows association between the type of congenital anomaly and gender. Congenital squint and congenital macula scar were significantly more common among females (p<0.001) and males (p = 0.04) respectively. Presentation within the first year of life was documented in 69 (51.9%) out of 133 children with congenital cataract; 38 (51.4%) out of 74 children with congenital squint; 35 (63.6%) out of 55 children with congenital glaucoma and 25 (78.1%) out of 32 children with congenital corneal opacity. Furthermore, 17 (53.1%) out of 32 children with nasolacrimal duct obstruction as well as 18 (52.9%) out of 34 children with congenital ptosis presented within the first year of life.

Discussion

Congenital ocular anomalies (COA) are global phenomena sparing no region of the world. It accounted for 13.6% of Paediatric ophthalmic consultations in this study. This is higher than 9.7% reported by Adekoya et al11 who analyzed 40 patients in another tertiary eye care Centre in Lagos, Nigeria. This disparity might be due to the smaller number of cases studied in the latter study. Prevalence of COA from previous studies from Nigeria ranged from 1.7% to 10.3%. [5-12] Eballe et al. [13] reported a prevalence of 6.65% among children aged 0-5 years in Cameroun while Kaimbo Wa Kaimbo et al. [14] reported a prevalence of 2.2% in Zaire. Furthermore, Ilechie et al. [8] reported a markedly high prevalence 54% in a Ghanaian Paediatric Eye Centre that receives referral from the whole country while Bermejo and Martinez-Friaz reported a prevalence of 3.68/10000 newborns in an analysis of consecutive births in Spain [9]. In the light of the foregoing, the prevalence of COA varies from country to country and from region to region within the same country.

In this study, COA was slightly more prevalent among males. Many authors had reported the predominance of COA among males [2-8,12]. On the contrary, Adekoya et al. [11] reported COA predominance among the females studied. This suggests that COA can affect both males and females. COA can be sporadic or inherited in an autosomal or X-linked pattern. It is the X-linked pattern of inheritance that usually has sex predilection. However, congenital squint and congenital macular scar were significantly more common among females and males respectively in this study. The reason for this is not clear and could be subject of further studies. Approximately three-fifth of the patients had bilateral affectation. This is in agreement with the observations of Adekoya et al. [11] and Lawan [7]. However, there was a slightly more involvement of the left eye in unilateral ocular COA compared to right eye involvement contrary to the findings of Adekoya et al. [11].

Congenital cataract was the most common COA in this study. It was also the most common unilateral and bilateral COA. This is in agreement with the findings of many previous studies both within and outside Africa [2-15]. However, it was the second most common COA from the observation of Eballe et al. [13], Lawan [7] as well as Bermejo and Martinez-Friaz [9]. Congenital cataract is one of the treatable causes of childhood blindness especially if intervention is timely. Unfortunately, nearly half of the patients in this study presented after the first year of life. In fact, oldest patient in this study was a 15 year old teenager with bilateral congenital cataract. This calls for concern knowing fully well that early intervention is key to visual restoration in congenital cataract. Late presentation/intervention increases the likelihood of development of sensory deprivation amblyopia with poor visual outcome even after surgical intervention. Late presentation has been reported among Paediatric cataract patients in previous studies from Africa [16-18]. Therefore, it is needful to sensitize health workers on the importance of checking for red reflex at birth as well as during well baby and immunization clinics to ensure early detection of congenital cataract. Also, the importance of early intervention in congenital cataract needs to be emphasized to parents and caregivers while giving health talks in such clinics.

Congenital squint accounted for 17.6% of COA in this study being the second most common. This is higher than the observations from previous studies from Nigeria which ranged from 1.9% to 9.7% [5-12]. The increased prevalence in this study could be attributed to the availability of strabismus surgical services in this centre. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment of congenital strabismus. Ilechie et al. [8] in Ghana reported a prevalence of 11.1% while Garg et al. [2] in India reported a prevalence of 3.5%.

Congenital glaucoma was the third most common COA in this study. This is similar to the findings of Adekoya et al. [11], Eballe et al. [13] and Kaimbo Wa Kaimbo et al. [14] It was the second most common COA reported by Garg et al. [2], Bodunde and Ajibode [5], Chuka-Okosa et al. [6], Ilechie et al. [8] as well as Osaguona and Okeigbemen [12].Congenital glaucoma usually presents with buphthalmos, cloudy cornea, lacrimation and photophobia [19]. The definitive treatment is surgery which include goniotomy, trabeculotomy, combined trabeculotomy and trabeculectomy, trabeculectomy, tube shunt implantation and ciliary body ablative procedures.19 Timely intervention ensures lowering of intraocular pressure and clarity of the cornea. However, late presentation leads to worsening cloudiness of the cornea and scarring thereby limiting the surgical options and jeopardizing a good visual outcome. In this study, only approximately two-third of the patients presented within the first year of life. Therefore, the importance of early presentation as well as early intervention cannot be overemphasized in congenital glaucoma.

Conclusion

Congenital ocular anomalies accounted for 13.6% of Paediatric ophthalmic consultations in this study. Congenital cataract, squint, glaucoma, corneal opacity, nasolacrimal duct obstruction and ptosis were the most common accounting for 79.0% of the congenital ocular anomalies observed.

Abbreviations

Congenital Ocular anomalies (COA), Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH).

Author’s contribution

All the authors contributed substantially to each of the four components mentioned below:

a. Concept and design of study or acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data;

b. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and

c. Final approval of the version to be published.

d. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of support in form of grant

None.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- WHO (2019) Congenital anomalies. World Health Organization Fact sheet, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Garg P, Qayum S, Dhingra P, Sidhu HK (2016) Congenital ocular deformities-leading cause of childhood blindness- A clinical profile study. Indian J Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2(1): 22-27.

- Guercio JR, Martyn LJ (2007) Congenital malformations of the eye and orbit. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 40(1): 113-140.

- Levin AV (2003) Congenital eye anomalies. Pediatr Clin North Am 50(1): 55-76.

- Bodunde OT, Ajibode HA (2006) Congenital eye diseases at Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria. Niger J Med 15(3): 291-294.

- Chuka Okosa CM, Magulike NO, Onyekonwu GC (2005) Congenital eye anomalies in Enugu, South-Eastern Nigeria. West Afr J Med 24(2): 112-114.

- Lawan A (2008) Congenital eye and adnexial anomalies in Kano, a five-year review. Niger J Med 17(1): 37-39.

- Ilechie AA, Essuman VA, Enyionam S (2013) Prevalence of congenital eye anomalies in a paediatric clinic in Ghana. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 19 (3): 76-80.

- Bermejo E, Martínez-Frías ML (1998) Congenital eye malformations: clinical-epidemiological analysis of 1,124,654 consecutive births in Spain. Am J Med Genet 75: 497-504.

- Blindness and Visual Impairment (2019).

- Adekoya BJ, Balogun MM, Balogun BG, Ngwu RA (2015) Spectrum of congenital defects of the eye and its adnexia in the pediatric age group; experience at a tertiary facility in Nigeria. Int Ophthalmol 35(3): 311-317.

- Osaguona VB, Okeigbemen VW (2014) Congenital Ophthalmic Anomalies in Benin City, Nigeria. Annals of Biomedical Sciences 13(1): 102-108.

- Eballe AO, Ellong A, Koki G, Nanfack NC, Dohvoma VA, et al. (2012) Eye malformations in Cameroonian children: a clinical survey. Clin Ophthalmol 6: 1607-1611.

- Kaimbo Wa Kaimbo D, Mwilambwe Wa Mwilambwe A, Kayembe DL, Leys A, Missoten L (1994) Congenital malformations of the eyeball and its appendices in Zaire. Bull Soc Belge Ophthalmol 254: 165-170.

- Riano Galan I, Rodriguez Dehli C, Garcia Lopez E, Moro Bayon C, Suarez Menendez E, et al. (2010) Frequency and clinical presentation of congenital ocular anomalies in Asturias 1990–2004. An Pediatr (Barc) 72: 250-256.

- Umar MM, Abubakar A, Achi I, Alhassan MB, Hassan A (2015) Pediatric cataract surgery in National Eye Centre Kaduna, Nigeria: outcome and challenges. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 22(1): 92-96.

- Ezegwui IR, Aghaji AE, Uche NJ, Onwasigwe EN (2011) Challenges in the management of pediatric cataract in a developing country. Int J Ophthalmol 4(1): 66-68.

- Mwende J, Bronsard A, Mosha M, Bowman R, Geneau R, et al. (2005) Delay in presentation to hospital for surgery for congenital and developmental cataract in Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol 89(11): 1478-1482.

- Bowling B (2016) Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology. A Systematic Approach. (8th edn). Elsevier, pp. 384-388.