Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6695

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6695)

Community-Based Participatory Research for Nutrition and Health Programs in the Caribbean: Using the Delphi Process to Create Sustainable Outcomes Volume 1 - Issue 2

Elizabeth D Wall-Bassett*1, Jacqueline Lancaster-Prevost2 and Marynese Titre2

- 1Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, University of Missouri USA

- 2Genetics Area Program, University of Missouri, USA

Received: April 02, 2018; Published: April 30, 2018

Corresponding author: Elizabeth D Wall-Bassett, PhD, RDN, Associate Professor, School of Health Sciences, Nutrition and Dietetics program, Western Carolina University, North Carolina, USA, 28723

DOI: 10.32474/LOJNHC.2018.01.000106

Abstract

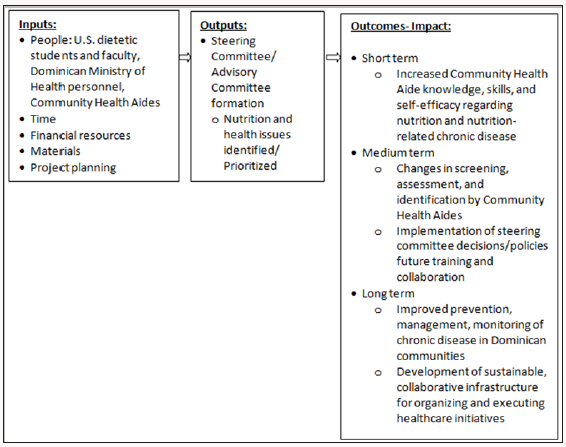

Background/Aim:A primary needs assessment was conducted in the Commonwealth of Dominica to determine priority areas of urgent intervention to improve health and nutrition while fostering knowledge and self-efficacy strategies.

Methods:The Delphi Method was employed to identify key areas for intervention. The main themes were sponsorship and support, community ownership, commitment of community and committee members to health and nutrition programs. Concerns which exist, or were perceived to exist at the community, household, or individual level were identified. During the first phase a Steering Committee composed of government officials and stakeholders in the Commonwealth of Dominica gathered to discuss health concerns. There were three rounds. During the third round, an Advisory Committee with a representative Community Health Aide from each health district was established and charged with acting as the intermediary to facilitate programs based on the suggestions brought forth from the Delphi process.

Results:During the final stage of the Delphi process the key areas identified for intervention were counseling techniques and alcohol abuse. The most ideal locations for interventions to be held were at local youth centers. Interactive media such a role plays, dramatizations and group discussion were reported as the best way to deliver future programs.

Conclusion:The Delphi Process in this study was effective at identifying themes related to health and nutrition concerns. This program set in motion sustainable initiatives that may be employed as a model for other Caribbean islands seeking to identify and prioritize themes for future health and nutrition intervention programs.

Keywords: Delphi; Community based participatory; Caribbean; Nutrition; Health; Socio-ecological model

Introduction

Nutritional transition characterized by an increased preference for high energy foods with low nutrient density in the diet [1-3] has been documented in numerous nations of the Caribbean [4- 8]. Due to the cost and distance associated with transporting food to the islands, accessibility to adequate and quality food is often compromised [9]. This decline in dietary quality is reflected in recent increases in chronic disease such as hypertension and high blood pressure [10,11]. On less economically developed islands, the influence of nutritional transition on disease is compounded by socio-economic factors including higher levels of unemployment and poverty [12].

The Dominican island is the largest of the eastern Caribbean islands. Until recently, Dominica had remained relatively isolated from external cultural and economic influences. However, recent developments due to a decline in agriculture sector which served as the main source of employment have facilitated the rapid influx of western foods [13,14] coupled with a growing prevalence in physical inactivity (men 14.9%, women 36,6%) in the population [10]. Approximately 50% of the population is overweight, and 25% is obese [10,11]. The prevalence of high blood pressure and elevated glucose levels is higher than the regional averages and women appear to be at higher risk than their male counterparts [10]. Although there is a desperate need for nutritional and health intervention, there is very little information available for the Caribbean. This is further complicated by the diversity of culture and diet from nation to nation. This gap in knowledge, coupled with the demand for health intervention, highlights the urgency for pioneering population specific studies and programs to affect health outcomes in this region.

The development of self- efficacy among key stakeholders through participation and the acquisition of resources are critical to the success of future interventions. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) involves community members and researchers to address problems and issues relevant to the community. The strength of an ecological framework is that it stresses the importance of addressing health problems at multiple levels (societal, community, organizational, intrapersonal, and individual) and accounts for the variability of behavioral determinants that range from individual and interpersonal factors to community norms, environments, and policies [15-17]. Multifactor collaborative socio-ecological models possess the potential to improve the health outcomes of subsequent generations by permanently modifying lifestyle choices, cultivating health awareness through improved knowledge risk factors associated with chronic disease as well as disease management [17]. Efficacious chronic disease prevention interventions must collectively address risks and opportunities at all five levels. A partnership between university researchers, Dominican community members, and the government of Dominica was framed by CBPR and socio- ecological models. The objective of this partnership was to develop and execute sustainable training and intervention strategies set out in the Health Plan of Dominica that can be exploited to improve health and nutrition while fostering knowledge and self-efficacy strategies. The aim of the Delphi Process was to identify priority areas for health and nutrition programs in Dominica.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in the Commonwealth of the Dominica, West Indies. The island has a population of approximately 73,897 people. The population is predominately black (86.6%) with minorities consisting of mixed descent (9.1%) and Carib Amerindians (2.9%) [18]. The Dominican economy relies heavily on tourism and agriculture. Approximately 29% of the population lives below the poverty line and 23% are unemployed. The current health care system and infrastructure dates back to the 1980s and comprises a tiered healthcare system. The Alma Ata declaration of 1978 addressed the need for health care to be available to the entire population. This was achieved by creating health care centers in villages with more than 600 people. A group of four to seven villages comprises a health district run by a district health team which consists of a District Medical Officer, Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP), a health Visitor, Environmental Health Officers, pharmacists and a dental therapist. There are seven districts in Dominica [19]. Cases that are too complex to be treated at the district level are referred to the main hospital.

Study design

The study was conducted as the second phase of the program Health Plan of Dominica. The first stage was a train-the-trainer workshop entitled “Sisserou Talks about Health and Nutrition” [20]. Trained dietetic students trained grassroots paraprofessionals and all community health aides that are instrumental in the provision of health education, risk assessment and primary care for the Dominican Community.

Participants

The panel from the Sisserou Talks included governmental and non-governmental representatives from organizations such as the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Education (School Feeding Program), Home Economics Association, Cancer Society, Food and Nutrition Council, and programs that provide assistance to children, women, families, and older adults was incorporated into the two-day workshop agenda. The panel provided public declarations of the health issues facing Dominica and identified internal service and provider partners. Participants of the train-the-trainer workshop also participated with researchers, government officials, and community members for the formation of Steering and Advisory committees (Figure 1).

Steering committee

Governmental and non-governmental representatives, key role models, researchers, and all Dominican Community Health Aides were invited as key informants to join a Steering Committee in Dominica. The purpose of the Steering Committee was to engage key stakeholders of the island in dialogue about health concerns (Figure 1).

Delphi process

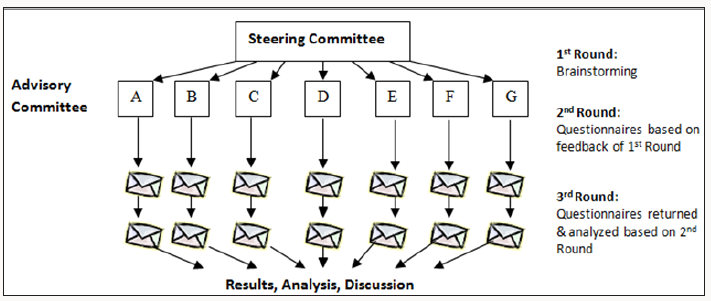

The Steering Committee members were recruited as participants for the Delphi Process. The Delphi Method was developed by the Rand Cooperation as a method to arrive at a consensus on strategy from a pool of experts [21]. Experts are queried repeatedly in three or more rounds until ideas are distilled to the most important or effective [22,23]; (Figure 2). Using the iterative Delphi method, the Steering Committee identified health concerns of the island relating to the themes sponsorship and support, community ownership, commitment of community and committee members to health and nutrition programs, and identification of concerns or problems which exist or were perceived to exist at the community, household, or individual level). Participants were asked to first individually write their responses to a list of three prompts: Identify priority areas for health and nutrition training in Dominica, list locations for delivering the trainings, and describe the best mode of delivery for the trainings. Group discussion followed around the individual responses (Figure 2).

Sampling

Participants for the Delphi Process were recruited from healthcare workers within the Ministries of Health and Education. Snowball sampling occurred as invited guests recommended others who they felt were influential in their communities. During the ‘first round’ held during the summer in 2009, response from structured surveys was gathered from the Steering Committee members [21-23]. Participants identified key role models in their communities that were instrumental in developing infrastructure for applying new knowledge and skills and positively impacting community and health of the island population; these role models were invited to the ‘second round’ of the Delphi process. A ‘second round’ was held eight months after the ’first round’ and it consisted of controlled feedback of Steering Committee perspectives and results of the ‘first round’. Controlled feedback uses an approach to present each committee member with a list of common questions; each committee member was asked to answer and reflect on the questions independently and then an intermediary collected the responses and shared them with the group for discussion. During the ‘second round’, the Steering Committee verified that the ‘first round’ responses reflected their opinions, and responses were changed or expanded upon. This ‘second round’ provided opportunity for clarification, direction of focus, and paring down of a list [23].

The ‘third round’ was held eight months after the ‘second round’. During the ‘third round’, the group decided to form an Advisory Committee with a representative Community Health Aide from each health district (7 health districts total). The Advisory Committee assessed the matters brought about through the ‘second round’ with further discussion in a ‘third round’. The Advisory Committee is the intermediary between communities and the Ministry of Health, and is charged with organizing future training workshops based on the suggestions brought forth from Delphi process. The Advisory Committee met again in June 2010 to discuss and develop a plan of action for health and nutrition training and activities in communities throughout Dominica. A summary of rounds one through three is presented in Table 1.

Data Analysis

Data obtained from semi-structured focus groups was analyzed using qualitative coding for themes [24]. To validate the data, Delphi Process participants reviewed the reports at the beginning of the ‘second’ and ‘third’ rounds, and the Advisory Committee reviewed the reports following the conclusion of the ‘third round’ in 2010. Discussion of themes concluded when consensus was reached. This study was reviewed and approved by the Behavioral and Social Science Committee for the East Carolina University Institutional Review Board.

Results

During the first round of the Delphi Process, the main themes reported included chronic disease, nutrition, pre-natal care, alcohol and drug abuse, HIV and safety and sanitation. Topics which were raised in the first round were revisited in the second round and the list was condensed to what the participants considered to be the most important or most urgent issues. Namely alcohol and drug abuse, chronic disease (obesity, hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus); overall nutrition (for all ages)/meal planning and budgeting, counseling techniques, and safety and sanitation were included in the list. At the end of the third round, training in counseling techniques and drugs and alcohol abuse were reported as areas in need of urgent attention.

There was a wide range of proposed venues and delivery media. Following the results from the final round the consensus was that public service training centers, schools, and youth centers would serve as the best venues for counseling training, and alcohol and drug abuse programs respectively. Generally, interactive forms of media such as role playing, dramatizations, singing and rapping were reported as the most effective means of delivering material. Detailed results of each round are presented in Table 1.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first time that such a study has been conducted in the Commonwealth of Dominica. The Delphi method in this setting was useful for short term predictions and the identification of the best policies to adopt. The focus groups were facilitated and structured by researchers, however, participatory research was employed to share control and adapt some of the topics based on the group input and experience [25]. A strength of the use of the Delphi method in this setting was since it followed an intensive workshop and training session, it helped foster ownership and self- efficacy among key stakeholders. The process also developed relationships between members of key agencies that whose unity is required for the success of future interventions. The Delphi method not only provided insight into how to make the intervention successful at a grassroots level, but it also initiated critical thinking and deliberation in the community on how to develop solutions to deal with their unique set of problems. The advantage of this system was to bring attention to concerns at all levels of the healthcare system, including those areas typically neglected.

Although the consensus was that the areas in most need of attention were alcohol and drug abuse; data from WHO indicate current prevalence of the Commonwealth of Dominica are comparable to those in the CARICOM region. In contrast, the prevalence of chronic disease as indicated by the prevalence of obesity and diabetes is rising [11]. A combination of scenarios may be occurring where by Dominicans are aware of the nutrition and chronic disease issues but they do not perceive it as manageable concern. Alternatively, alcohol or drug abuse may be appearing as a novel social problem which is igniting concern as indicated by the responses combined with some of the chronic disease outcomes.

Social problems arising from alcohol and or drug abuse may have far reaching consequences in tight knit family oriented communities such as Dominica. Therefore, the effects of substance abuse problems may be more conspicuous thus perceived as more important to communities in Dominica. More investigation is required to provide an in depth understanding of dynamics affecting the Dominican community. The quality of information from this study may have been improved by stratifying the needs by age group. The dietary and social influences on both the younger and older generation differ vastly and the interventions needs of one may not be applicable to another. Through prevention measures, especially among younger generations, attention can be placed on some of multi-facets of chronic disease.

Community-based participatory research and the use of the socio-ecological model can be extremely useful tools for developing a larger base of knowledge, increasing health awareness, improving risk assessment and management of prevalent conditions, generating supportive mechanisms, and expanding outreach. This participatory model can be influential in improving the health and decreasing healthcare costs for Dominicans and similar populations in the Caribbean. Over time, the hope is for training on nutrition and health in communities in Dominica to contribute to a decrease in healthcare costs for this population by enhancing knowledge and prevention measures in the community. It is not only the acquisition of knowledge, but also the management and prevention action steps that can influence health and decrease healthcare costs.

Conclusion

The Delphi Process was effective at identifying themes related to health and nutrition concerns, and prioritizing them for future training and education programs for Community Health Aides and for communities in Dominica. Through this CBPR/socio-ecological program, committee members reflected that they felt a part of a team for beneficial outcomes in Dominican communities. This program set in motion sustainable initiatives that can be used as a model for other Caribbean islands in the regions seeking to integrate health and nutrition training and education programs.

Acknowledgement

It is with due appreciation to many people for their contributions and talents in the development, delivery, and analysis of this study. We would like to thank the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Health in Dominica, specifically Alison Samuel, Joan Henry, and Davis Letang for their tremendous organization, diligence, and dedication to this program and benefiting health programs and outcomes in Dominica. We are also grateful for the help with preparation of materials and the careful review assistance of Nancy Harris, Shelby Donnelly, Jamie Hopkins, Laura Gantt, Lalage Katunga and Lynette Spencer at East Carolina University.

References

- Popkin BM, Adair LS, Shu WN (2012) Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev 70(1): 3-21.

- Popkin BM (2009) Global changes in diet and activity patterns as drivers of the nutrition transition. Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series. Paediatric Programme 63: 1-10.

- Goodland R (2001) The westernization of diets: The assessment of impacts in developing countries with special reference to China.

- Albert JL, Samuda PM, Molina V, Regis TM, Severin M, et al. (2007) Developing food-based dietary guidelines to promote healthy diets and lifestyles in the Eastern Caribbean. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 39(6): 343-350.

- Sheehy T, Sharma S (2010) The nutrition transition in Barbados: Trends in macronutrient supply from 1961 to 2003. The British Journal of Nutrition 104(8): 1222-1229.

- Gardner K, Bird J, Canning PM, Frizzell LM, Smith LM (2011) Prevalence of overweight, obesity and underweight among 5-year-old children in Saint Lucia by three methods of classification and a comparison with historical rates. Child: Care Health Dev 37(1): 143-149.

- Luke A, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Cao G, Forrester TE, Wilks RJ, et al. (2007) Activity, adiposity and weight change in Jamaican adults. The West Indian Medical Journal 56(5): 398-403.

- Schwiebbe L, Van Rest J, Verhagen E, Visser RW, Holthe JK, et al. (2011) Childhood obesity in the Caribbean. The West Indian Medical Journal 60(4): 442-445.

- (2004) Uses of food consumption and anthropometric surveys in the Caribbean: How to transform data into decision making tools. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

- (2011) World Health Organization (WHO) Dominica, overweight, obesity.

- (2012) Pan American Health Organization in World health indicator database, Dominica, Caribbean, Central America.

- (2003) Caribbean Development Bank Caribbean Development Bank, government of the Commonwealth of Dominica country poverty assessment. Halcrow Group, London.

- (2003) Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute FAO nutrition country profiles-Food and Agriculture Organization.

- (1996) The Dominica Food and Nutrition Council in Collaboration with the Government of Dominica and the Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute. Dominica food consumption pattern and lifestyle survey.

- Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, et al. (2006) An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annual Review of Public Health 27: 297-322.

- Breslow L (1996) Social ecological strategies for promoting healthy lifestyles. American Journal of Health Promotion 10: 253-257.

- Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F (1999) Dissecting obesogenic environments: The development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med 29(6): 563-570.

- (2018) Central Intelligence Agency CIA-the World Factbook, Dominica, Caribbean, Central America.

- Kolkman PM, Luteijn AJ, Nasiiro RS, Bruney V, Smith RJ, et al. (1998) District nursing in Dominica. Int J Nursing Studies 35(5): 259-264.

- Wall-BE, Harris N (2017) Promoting Cultural Competency: A Nutrition Education Model for Preparing Dietetic Students and Training Paraprofessionals in an International Setting. Global Journal of Health Science 9(9): 108-116.

- Adler M, Ziglio E (1995) Gazing into the oracle: The Delphi method and its application to social policy and public health. (1st edn), Jessica Kingsley Publishers, Philadelphia, USA.

- Linstone H, Turloff M (2002) The Delphi method: Techniques and applications. Addison-Wesley Company, Massachusetts, USA.

- Schmidt R (1997) Managing Delphi surveys using nonparametric statistical techniques. Decision Sciences 28(3): 763-774.

- Creswell JW (2009) In: Thousand Oaks (Ed.), Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. (3rd edn), Sage Publication, California, USA.

- Greenwood D, Morten L (1998) In: Thousand Oaks (Ed.), Introduction to action research: social research for social change. Sage Publications, California, USA.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...