Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6628

Case Report(ISSN: 2637-6628)

Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak at the Clivus: Two Case Reports and Literature Review Volume 5 - Issue 1

Mohammad Samadian1, Seyed Ali Mousavinejad1*, Hamid Borghei-Razavi2, Guive sharifi1, Kaveh Ebrahimzadeh1, Kristen Almagro2 and Omidvar Rezaei1

- 1Department of Neurosurgery, Loghman Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Neurosurgery, Pauline Braathen Neurological Center, Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston, Florida,USA

Received: December 02, 2020; Published:December 11, 2020

Corresponding author: Seyed Ali Mousavinejad, Assistant professor of neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery, Loghman Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

DOI: 10.32474/OJNBD.2020.05.000201

Abstract

Introduction: Spontaneous or non-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leaks comprise 5–10% of all csf rhinorrhea. Generally csf rhinorrhea occur at Cribriform plate, sella, sphenoid sinus and ethmoid air . Primary csf rhinorrhea from clival defect is extremely rare. We herein describe two cases of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea through the clivus repaired with endoscopic endonasal trans sphenoid approach. Moreover, we collected evidence in the literature regarding potential etiology, symptom and treatment (which occurred in the case reported).

Background: Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks comprise 5–10% of all CSF rhinorrhea. Generally, CSF rhinorrhea occur at cribriform plate, sella, sphenoid sinus and ethmoid air. Primary CSF rhinorrhea from clival defect is extremely rare. we describe two cases of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea through the clivus defect and review the literature.

Case Description: The first patient was a 36 -year-old female admitted to our department because of clear watery discharge from the right nostril of 3 weeks which aggravated in prone position. The second case was a 57-year-old man referred to our department with the complaint of intermittent rhinorrhea starting 6 months before surgery. He had a past history of bacterial meningitis few month before stating the rhinorrhea which was treated in another center. In both cases, testing of the fluid for beta-2 transferrin was positive. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography cisternogram showed CSF leak through clivus into the sphenoid sinus. In both patients defect was repaired with abdominal fat, reinforced by fascia lata and naso septal flap via “two nostrils – four hands” endoscopic trans nasal technique.

Conclusion: At times, the exact pathophysiology of CSF clival fistula is debated, however a combination of anatomical and functional factors play a role in the occurrence of this rare phenomenon. To date, only 16 cases are reported, and the current study reported a group of two consecutive cases. To date, endoscopic trans nasal approach is the best therapeutic option to repair midline skull base defect such as the current cases.

Keywords:Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak; Rhinorrhea; Clivus; Meningitis; Endoscopic Endonasal Approach

Introduction

Spontaneous or non-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leaks

comprise 5%–10% of all cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea

[1,2]. Generally, CSF rhinorrhea can occur at the cribriform plate,

sella, sphenoid sinus, or ethmoid air cells [3,4]. However, primary

CSF rhinorrhea due to clival defect is extremely rare. The current

study describes two cases of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea through

the clivus which were repaired with endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal

approach.

Such cases are extremely rare and upon literature review, only

16 cases with clival defect are reported thus far.

The peculiar aspect of this case report is related to its rarity.

Moreover, evidence was collected from the literature regarding potential etiology, symptom, and treatment (occurred in the

reported cases).

Case 1

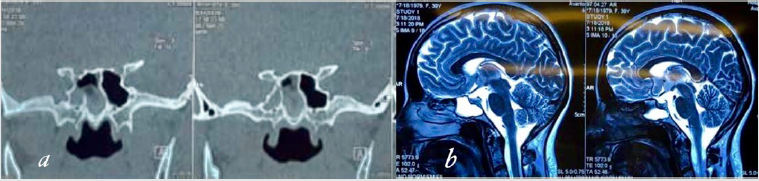

A 36 -year-old female was admitted for three weeks of clear watery discharge from the right nostril, which was aggravated in prone position. The patient denied any recent trauma. A review of systems was negative except for headaches and nasal discharge. The nasal fluid tested positive for beta-2 transferrin, indicating that the fluid was CSF. Brain MRI revealed that the sphenoid sinus was filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and sagittal T2 weighted MRI revealed a fistula tract from prepontine cistern to sphenoid sinus (Figure 1). There was no evidence of benign intracranial hypertension. Computed tomography cisternography revealed that the contrast material passed from the prepontine cistern into the sphenoid sinus through this bone defect in the clivus (Figure 1). Before surgery, a lumbar puncture was performed to administer 0.25 mL of 10% fluorescein with 10mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to help visualize CSF leaks during surgery and to ensure there was no leak after reconstruction of the defect.

Figure 1:(a) Coronal CT cisternography shows sphenoid sinus filled with CSF.(b) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the brain showing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak into the sphenoid sinus trough clival defect.

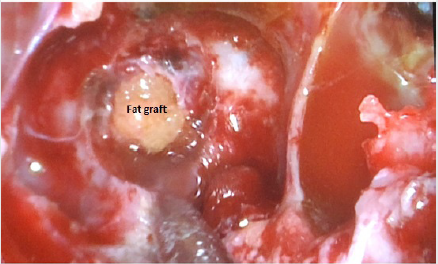

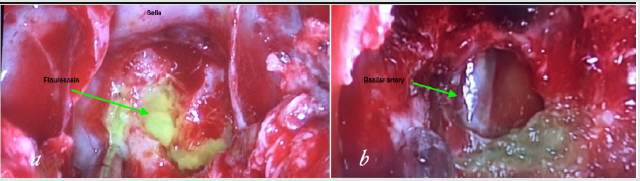

The patient underwent endoscopic trans nasal trans sphenoid surgery. The anterior and middle portions of the clivus were exposed between both carotid arteries. During surgery, the defect was defined to the left of the midline in the clivus. The basilar artery was seen through the defect in prepontine cistern (Figure 2). The defect was closed with a multilayer reconstruction consisting of fat, fascia lata, and naso septal flap (Figure 3). There was no recurrence of CSF leak at 2 years follow-up.

Figure 2:(a) Intraoperative endoscopic view show CSF leakage from clivus defect just inferior to the sella . (b) Basilar artery in prepontine cistern behind the defect.

Case 2

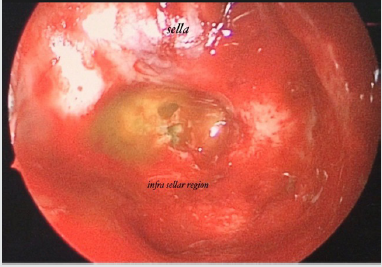

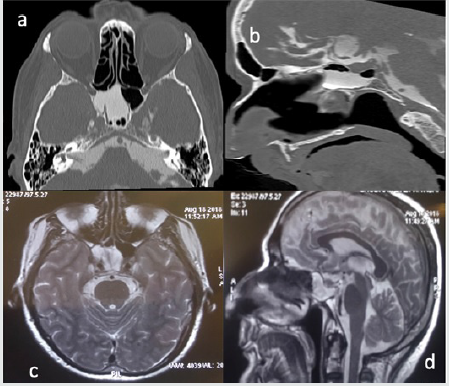

A 57-year-old man referred for clear watery discharge from the right nostril of no obvious cause. He suffered from intermittent rhinorrhea starting 6 months prior to arrival. He reported recent history of bacterial meningitis one month ago , which was treated successfully at an outside hospital. On admission, he had no focal neurological deficits. Nasal fluid tested positive for beta2 transferrin. Brain MRI revealed that the right sphenoid sinus was filled with CSF (Figure 4). CT cisternography showed that the contrast material passed from the prepontine cistern into the sphenoid sinus through this bone defect in the clivus (Figure 4). After intrathecal administration of 0.25 mL of 10% fluorescein with 10 mL of cerebrospinal fluid the patient underwent endoscopic trans nasal approach. After stripping the mucosa from posterior wall of sphenoid sinus, CSF leak was observed in the upper region of clivus just below the sella at the midline (Figure 5). The defect was closed by abdominal fat and reinforced by fascia lata and naso septal flap. At the During 30-month follow-up appointment, no signs of recurrence were found. In both of the above reviewed cases, a lumbar drain was not placed pre or postoperatively.

Figure 4:(a) CT cisternography showing right sphenoid sinus filled with CSF and (b) the entry of cerebrospinal fluid into the sphenoid sinus. (c) Axial T 2 weight MRI revealed right sphenoid sinus filled with CSF. (d) Sagittal T2 MRI shows CSF leakage from prepontine cistern to sphenoid sinus.

Discussion

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks most commonly result from

nonsurgical trauma (80%-90% of cases), followed by surgical

procedures (16%), and nontraumatic or spontaneous causes (4%)

[5,6]. O’Connell first subcategorized spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea in

two groups in 1964; primary spontaneous, when there is no cause

for skull defect, and secondary spontaneous, when a cause can be

found [7,8] Defects in the roof of the ethmoid sinus or in the floor of the anterior cranial fossa contribute to the most common site

of fistula in the patient with traumatic CSF rhinorrhea. However,

for primary spontaneous CSF fistulas, a sphenoidal fistula is most

common (60%).

In these cases the junction of the floor of the middle cranial

fossa to the lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus is the most common

site of CSF leak through sphenoid sinus, [3] however, primary

spontaneous CSF leaks from clival defect are extremely rare. In

a study by Hooper on 138 sphenoid bones, the defect of bones

connecting the sphenoid to the cranium leading to CSF leak was

observed in 5% of cases; all of which were in lateral wall of the

sphenoid sinus [9,10]. To the best of the authors knowledge, only

16 cases of spontaneous CSF leaks from clival defect are reported

thus far. The exact pathophysiology of CSF clival fistula is debated.

Morley and Wortzman postulated that congenital bone defects in

the middle fossa can explain the leaks through the lateral extensions

of the sphenoid sinus [11]. However, from anatomic point of view,

there is no clear embryological evidence to explain clival defect

causing CSF rhinorrhea.

The clivus is a bony structure composed of the fusion of

the posterior portion of the sphenoid body (basisphenoid)

and the basilar part of the occipital bone (basioccipital) at the

sphenooccipital synchondrosis (SOS). SOS fusion can occur at

any age, but it usually happens before adolescence. SOS may

persist into adult life and may be mistaken for a fracture or defect.

However, this synchondrosis is caudal to the future sphenoid sinus;

otherwise, clival ossification would be a continuous enchorial

ossification without fusion point that could explain bone defect

[12,13]. According to Faizuddin Ahmad et al. most authors believe

that excessive pneumatization of sphenoid sinus causes a thin bony

wall at some points of clivus and sphenoid. These phenomena,

combined with other potential factors such as arterial pulsation and

continuous CSF pressure wave ultimately lead to the bone defect at

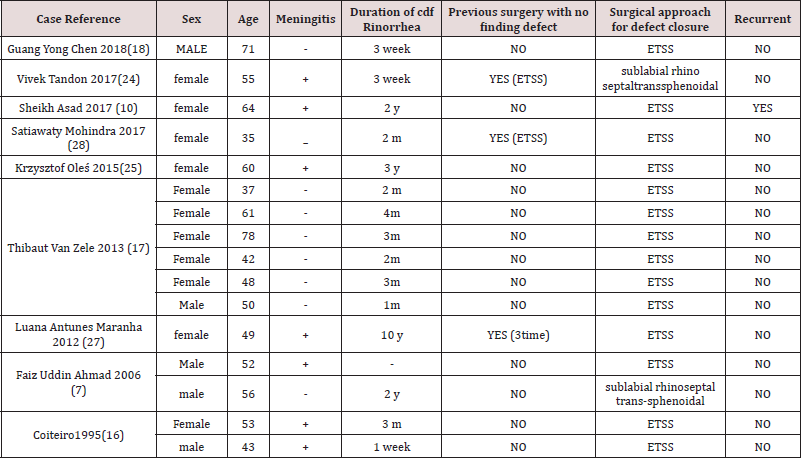

the clivus and CSF leak [7,14,15]. Sixteen cases of spontaneous CSF

leak at the clivus were reported from 1995 to 2018 (Table1). In all

patients, the defect was localized in the upper clivus. In all sixteen

cases reported thus far CSF leak from clival defect occurred in adult

patients, which may explain the role of CSF pressure pulsation

as a predisposing factor. The CSF pressure pulsation reaches its

maximum point in adults, approximately three times higher than

that of infants. Eleven of the sixteen patients were female. In 1995,

Coitero et al., reported the first two cases of CSF fistula through the

clivus. In one case they suggested that basilar artery pulsations over

a thinned bone structure could be the cause of clival defect [16].

Radiographic features of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) such

as empty sella syndrome (80%) and arachnoid pits (63%) are often

observed in patients with spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea. However,

in a case report by Thibaut van Zele in spontaneous clival CSF leak,

radiologic signs of increased ICP (empty sella and/or arachnoid

pits) were observed only in two cases of four patients [17].

In all of the current study patients, the CSF pressure was normal

and magnetic resonance findings were not suggestive of benign

intracranial hypertension. Radiologic evaluation of CSF leaks is a

diagnostic challenge that often involves multiple imaging studies.

Various imaging studies such as contrast-enhanced computed

tomography (CT) cisternography, radionuclide cisternography, and

MR cisternography are employed in the diagnosis of such cases. To

date, contrast-enhanced CT cisternography is the standard for CSF

leak evaluation with a sensitivity of 76-100% [18,19].

However, cisternography requires intrathecal injection

via lumbar puncture which can cause discomfort for patients.

Additionally, CSF leak is often an intermittent phenomenon,

therefore the sensitivity of cisternography depends on the timing

of the examination. Additional MRI (with T2-weighted sequences)

can be helpful if parenchymal or meningeal herniation is suspected

[20,21]. Of the above referenced two case studies, one patient’s

sphenoid sinus was filled with cerebrospinal fluid and defect was

discovered in the upper part of the clivus.

Retrospectively, in cases suspected of clival defect, the T2-

weighted sequence of mid-sagittal MRI showed CSF fistula from

prepontine cisterna to sphenoid sinus. Several surgical approaches

can be utilized to repair CSF rhinorrhea. However, to date endoscopic

trans nasal trans sphenoid surgery is established as the standard

technique to repair CSF leak. This approach is less invasive, with

lower morbidity and mortality, excellent view of the surgical field,

and a higher success rate [22-25]. In the current study, endoscopic

trans nasal approach was performed for fistula repair in both

patients. All defects were closed with a combination of fat, fascia,

and a free or nasoseptal flap. Review of the literature highlighted

the fact that identification of the bone/dural defect responsible for

CSF leakage was the most important point for successful surgical

intervention, since a missed site can lead to improper treatment

and recurrence of the leak [25,26].

In a report by Vivek Tandon, sphenoid sinus packing was

performed when the exact site of the leak was not identified, and

the patient presented with recurrent rhinorrhea and meningitis

[24]. In a report by Luana Antunes Maranha, the patient underwent

anterior skull base repair via bifrontal craniotomy three times

since the exact site of leakage was not defined and the patient

presented with recurrent CSF leak. Finally, the patient underwent

endoscopic trans nasal approach for clival defect closure [27]. In

some cases, there is more than one defect that should be repaired.

For example, in a study by Satiawaty Mohindra, a patient had two

concomitant defects. In the first surgery, clival defect was missed;

the right cribriform plate and right sphenoid sinus defect closures

were performed. CSF rhinorrhea recurred after one month and the

patient underwent revision surgery. In revision surgery, previous

repair site did not show leakage, but a high-pressure leak was

observed through posterior wall of sphenoid sinus from clivus [28].

In all of the current study patients, clival defect was the

only defect causing CSF leak. To date, various materials such as

mucoperichondrium, cartilage, fat, fascia, and fibrin glue have been

utilized to seal the fistula with different success rates. Fat and fascia

were used for defect closure in all of the patients in the current

study, comparable to patients with spontaneous CSF leak or repair

of dural defect after adenoma surgery. Similar to Hegazy, we believe

that the material used in the closure of the fistula is not important

in the success of the intervention. The important key to success is

the determination of the bony edge surrounding the defect [29].

Similar to the other authors, we reserved lumbar drainage for

patients with elevated intracranial pressure. In both patients, the

conservative measures such as bed rest, elevation of the head, and

avoidance of straining activities were implemented after surgery

[30,31].

Conclusion

Spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea located at the clivus is an extremely

rare condition. To date, only 16 cases are reported, and the current

study reported a group of two consecutive cases. It seems that a

combination of anatomical and functional factors play a role in the

occurrence of this rare phenomenon. To date, endoscopic trans

nasal approach is the best therapeutic option to repair midline skull

base defect such as the current cases.

Here, the initial outcome was successful, but long-term followup

is required.

References

- Pérez MA, Bialer OY, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V (2013) Primary spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology 33(4): 330-337.

- Bledsoe JM, Moore EJ, Link MJ (2009) Refractory cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea secondary to occult superior vena cava syndrome and benign intracranial hypertension: diagnosis and management. Skull Base 19(4): 279-285.

- Lopatin AS, Kapitanov DN, Potapov AA (2003) Endonasal endoscopic repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 129(8): 859-863.

- Hubbard JL, McDonald TJ, Pearson BW, Laws Jr ER (1985) Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: evolving concepts in diagnosis and surgical management based on the Mayo Clinic experience from 1970 through 1981. Neurosurgery 16(3): 314-321.

- Psaltis AJ, Schlosser RJ, Banks CA, Yawn J, Soler ZM (2012) A systematic review of the endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 147(2): 196-203.

- Sharifi G, Mousavinejad SA, Bahrami-Motlagh H, Eftekharian A, Samadian M, et al. (2019) Delay posttraumatic paradoxical cerebrospinal fluid leak with recurrent meningitis. Asian journal of neurosurgery 14(3): 964-966.

- Ahmad FU, Sharma BS, Garg A, Chandra PS (2008) Primary spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea through the clivus: possible etiopathology. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 15(11): 1304-1308.

- O'connell JE (1964) Primary spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry 27(3): 241.

- Hooper A (1971) Sphenoidal defects—a possible cause of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 34(6): 739-742.

- Asad S, Peters-Willke J, Brennan W, Asad S (2017) Clival defect with primary CSF rhinorrhea: a very rare presentation with challenging management. World neurosurgery 106: 1052. e1-1052. e4.

- Morley T, Wortzman G (1965) The importance of the lateral extensions of the sphenoidal sinus in post-traumatic cerebrospinal rhinorrhoea and meningitis: clinical and radiological aspects. Journal of neurosurgery 22(4): 326-332.

- Shetty PG, Shroff MM, Fatterpekar GM, Sahani DV, Kirtane MV (2000) A retrospective analysis of spontaneous sphenoid sinus fistula: MR and CT findings. American journal of neuroradiology 21(2): 337-342.

- Langman J (1981) Medical Embryology. Williams & Wilkins, United States.

- Calcaterra TC (1980) Extracranial surgical repair of cerebrospinal rhinorrhea. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 89(2): 108-116.

- Haetinger RG, Navarro JA, Liberti EA (2006) Basilar expansion of the human sphenoidal sinus: an integrated anatomical and computerized tomography study. European radiology 16(9): 2092-2099.

- Coiteiro D, Távora L, Antunes JL (1995) Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid fistula through the clivus: report of two cases. Neurosurgery 37(4): 826-828.

- Van Zele T, Kitice A, Vellutini E, Balsalobre L, Stamm A (2013) Primary spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks located at the clivus. Allergy & Rhinology 4(2): e100-e104.

- Guang Yong Chen, Long Ma, Mei Ling Xu, Jin Nan Zhang, Zhi Dong He, et al. (2018) Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: A case report and analysis. Medicine 97(5): e9758.

- Reddy M, Baugnon K (2017) Imaging of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea and otorrhea. Radiologic Clinics 55(1): 167-187.

- Algin O, Hakyemez B, Gokalp G, Ozcan T, Korfali E, et al. (2010) The contribution of 3D-CISS and contrast-enhanced MR cisternography in detecting cerebrospinal fluid leak in patients with rhinorrhoea. The British journal of radiology 83(987): 225-232.

- Hegarty S, Millar J (1997) MRI in the localization of CSF fistulae: is it of any value? Clinical radiology 52(10): 768-770.

- Muscatello L, Lenzi R, Dallan I, Seccia V, Marchetti M, et al. (2010) Endoscopic transnasal management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks of the sphenoid sinus. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 38(5): 396-402.

- Elrahman HA, Malinvaud D, Bonfils NA, Daoud R, Mimoun M, et al. (2009) Endoscopic management of idiopathic spontaneous skull base fistula through the clivus. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 135(3): 311-315.

- Tandon V, Garg K, Suri A, Garg A (2017) Clival defect causing primary spontaneous rhinorrhea. Asian journal of neurosurgery 12(2): 328-330.

- Oleś K, Składzien J, Betlej M, Chrzan R, Mika J (2015) Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak at the clivus. Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques 10(4): 593-599.

- Virk JS, Elmiyeh B, Saleh HA (2013) Endoscopic management of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: the charing cross experience. Journal of Neurological Surgery Part B: Skull Base 74(2): 61-67.

- Maranha LA, Corredato RdA, Araújo JC (2012) Nontraumatic clival cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria 70(7): 550-551.

- Satyawati Mohindra, Sandeep Mohindra, Joshi dk, Sodhi HB (2017) Delayed Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Leak through Clival Recess: Emphasis on Technique of Repair. Clinical Rhinology 10(1): 42-44.

- Hegazy HM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Kassam A, Zweig J (2000) Transnasal endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: a meta‐analysis. Laryngoscope 110(7): 1166-1172.

- Casiano RR, Jassir D (1999) Endoscopic cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea repair: is a lumbar drain necessary? Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 121(6): 745-750.

- Yadav YR, Parihar V, Janakiram N, Pande S, Bajaj J, et al. (2016) Endoscopic management of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Asian journal of neurosurgery 11(3): 183-193.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...