Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6628

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6628)

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Established E-Cigarette, Cigarette, and Dual Users Among Adults in the US Volume 3 - Issue 5

Rehab Auf1*, Marah Selim2 and Mary Jo Trepka3

- 1Department of Health, Human Performance, and leisure (HHPL), College of Arts and Science (COAS), Howard University, Washington, USA

- 2College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, USA

- 3Department of Epidemiology, Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work, Florida International University, Miami, USA

Received: January 24, 2020; Published: February 19, 2020

Corresponding author: Rehab Auf, Department of Health, Human Performance, and leisure, College of Arts and Science, Howard University, Washington, USA

DOI: 10.32474/OJNBD.2020.03.000174

Abstract

Background: No previous research examined the sociodemographic characteristics of established e-cigarette users. Towards this end, we aimed to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of established e-cigarette, established cigarette, and established dual users.

Methods: Data from the first wave of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study was used to describe characteristics of established cigarette and established dual users. The adjusted odds ratio was estimated for each tobacco use group controlling for all other variables in the models.

Results: Among the 32,180 participants, 10,385 (32.3%) established cigarette smokers, 578 (1.8%) established e-cigarette users, 996 (3.1%) dual users were identified. The highest proportion of established e-cigarette and cigarette use was in the South and the least in the Northeast. Established cigarette users had higher odds of being White, male, between 24-65 years, not a student and having less than high school education or GED, a household income < 24.99$K, no children in their household, and failing to pay some bills. Established e-cigarette users had a higher odd of being White, between 25 and 54 years and having less than four years college education, an income < 100$K, and no children in their household. There was no difference by gender, student status or ability to pay bills.

Conclusions: Established e-cigarettes use, unlike for the cigarette use group, did not vary by gender household income, or student status. These different characteristics warrant further research to address new population groups at risk of tobacco use.

Keywords: Tobacco Use; E-Cigarettes; Cigarettes; Dual Tobacco Use; Sociodemographic; PATH Study

Introduction

E-cigarettes are battery operated devices that vaporize aerosols, mostly containing nicotine [1]. Since May 2016, e-cigarettes are being regulated in the United States (US) as tobacco products by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [2]. They were first introduced into the American market prior to 2006 [3], but their use started to be notable and increasing from 2010. For example, the past 30-day of e-cigarette use almost tripled from 1.0% in 2010 to 2.6% in 2013 and continued to increase by 2014 to 4.8% among adults in the US [4,5]. In 2016, the past 30 days e-cigarette use declined to 3.2% among adults in the US [6], the reasons for this decline is not fully explored. But one possibility is the increasing awareness of health negative effects of e-cigarettes might lead to this slight decline in its use. E-cigarettes are being advertised as a smoking cessation aid and a “less harmful” alternative for tobacco products [7]. Unfortunately, in addition to nicotine, e-cigarettes aerosols might contain variable concentrations of potentially harmful constituents such as heavy metals, ultrafine particulate, and volatile organic compounds [8]. Long term effects of e-cigarettes have not yet been unraveled [9,10]. There is limited scientific evidence to prove the efficiency of e-cigarette in long term smoking cessation [11]. Also, e-cigarettes are not approved by the FDA as a smoking cessation aid in the US. Most importantly, the reported association between e-cigarettes use among never smokers and subsequent tobacco use is concerning and warrants careful monitoring and control for e-cigarettes [12,13]. Moreover, it is concerning that dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes might expand the use of both products simultaneously without any reduction in tobacco use [14]. For example, many cigarette smokers reported dual use of e-cigarettes as an alternative at times and in places where they cannot smoke [15,16]. E-cigarettes might also renormalize tobacco use [17]. Such possibility suggests that the number of consumed cigarettes might be reduced, but people would continue to use tobacco. Therefore, dual use might not reduce the duration of smoking [18]. Since the risk associated with tobacco use depends on the duration of smoking and it is non-linear i.e. light smoking exposes individual to high risk of various morbidity and mortality [19], dual use might not reduce the risk of tobacco use. Therefore, it is important to examine dual use in different research contexts. Sociodemographic characteristics profiling for tobacco users is important to identify individuals at higher risk of tobacco use to target in prevention and control programs. There have been extended research on the sociodemographic characteristics for cigarette. However, this area has been under explored for e-cigarettes. For example, previous research focused on adolescents, limited region, nonrepresentative sample for the US or examined ever or past 30 days e-cigarette use which does not measure the establishment of e-cigarette use [20-23]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine the sociodemographic characteristics of established e-cigarette, cigarette, and dual user participants of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study’s first wave, which had a representative sample of the US population. Established e-cigarette use reflects habitual behavior rather than experimental one, which might be the case for “ever” or “past 30 days” use as employed in most published research. Also, this allows for a better comparison between established cigarette users and established cigarette users, which this study aimed to do.

Methods

Study Population: This is a secondary analysis of the adult data from the first wave of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. The PATH Study is a collaboration between the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The data are deposited in public access resource with some restricted access files. The current study is based on the public access data only. In wave one of the adult surveys, a total of 32,320 individuals 18 years or older were interviewed from all the 50 states and the District of Columbia in the United States (US). Computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) was used for household screening, and audio computer assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) was used to complete the interviews. The study design, sampling, and procedures were published elsewhere [24,25]. However, in brief, they study used a four-stage stratified area probability sample design, with a two-phase design for sampling the adult cohort at the final stage. A detailed description of the design can be found in the User’s Guide to the restricted use files (RUFs), available at http://doi. org/10.3886/ICPSR36231. The study oversampled young adults (18-24 years), tobacco users, and African-Americans. Participants were enrolled between the years for 2013 and 2014. The PATH study was approved by Westat’s institutional review board (original study review board).

Measures

The PATH study included detailed information on e-cigarettes and cigarette use. It also included demographic and some socioeconomic variables. We opted to use the “established use” rather than ever or past 30 days to better reflect habitual practice rather than occasional or experimental one for e-cigarette and cigarette use as below.

E-cigarette use

Established e-cigarette users were defined as participants who had ever used an e-cigarette, had used it fairly regularly, and used e-cigarette every day or some days. We used the readily constructed variable at the public access data.

Cigarette use

Established cigarette users were defined as participants who had ever smoked a cigarette, had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in lifetime, and currently smoked every day or some days. We used the readily constructed variable at public access data.

Dual use:

Dual users were defined as those who were simultaneously established e-cigarette and cigarette users. A single variable was constructed to combine established cigarette and e-cigarette use variables into established e-cigarette users, established cigarette users, established dual users (who used both products), and those who were neither e-cigarette nor cigarette established users i.e. the rest of the population.

Demographic measures

We used the age variable grouped in seven categories; gender, education grouped at six levels; and being current student. We joined race and ethnicity into one variable that was grouped into White, Black, Hispanic, and other races were collapsed into “others”. We used the four regions of the US (South, West, Northeast, and Midwest) to describe the geographic locations of each of the study groups.

Economic factors

The annual household income, failure to pay bill in the past 30 days, and having children in the household were included to reflect the economic burden.

Analysis

The established cigarette and e-cigarette use variable was used to categorize the study population into four groups: 1) established e-cigarette users, 2) established cigarette users, 3) established dual users, and 4) others who were neither established user for cigarettes or e-cigarettes. This variable was used to describe the characteristics for each group. Missing data accounted for < 5% and were excluded from the analysis. Chi Square test was used to test statistical difference in sociodemographic characteristics among the four groups. Three separate logistic regression models were conducted to estimate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The first model estimated the odds of the likelihood of being an established cigarette user compared to others who were neither established user for cigarettes or e-cigarettes in respect to the included demographic and economic variables. The other two models repeated the same for established e-cigarette users and dual users. The logistic regression models compared the three established user groups in reference to those who were not established users to identify their characteristics in comparison to the general population.

Results

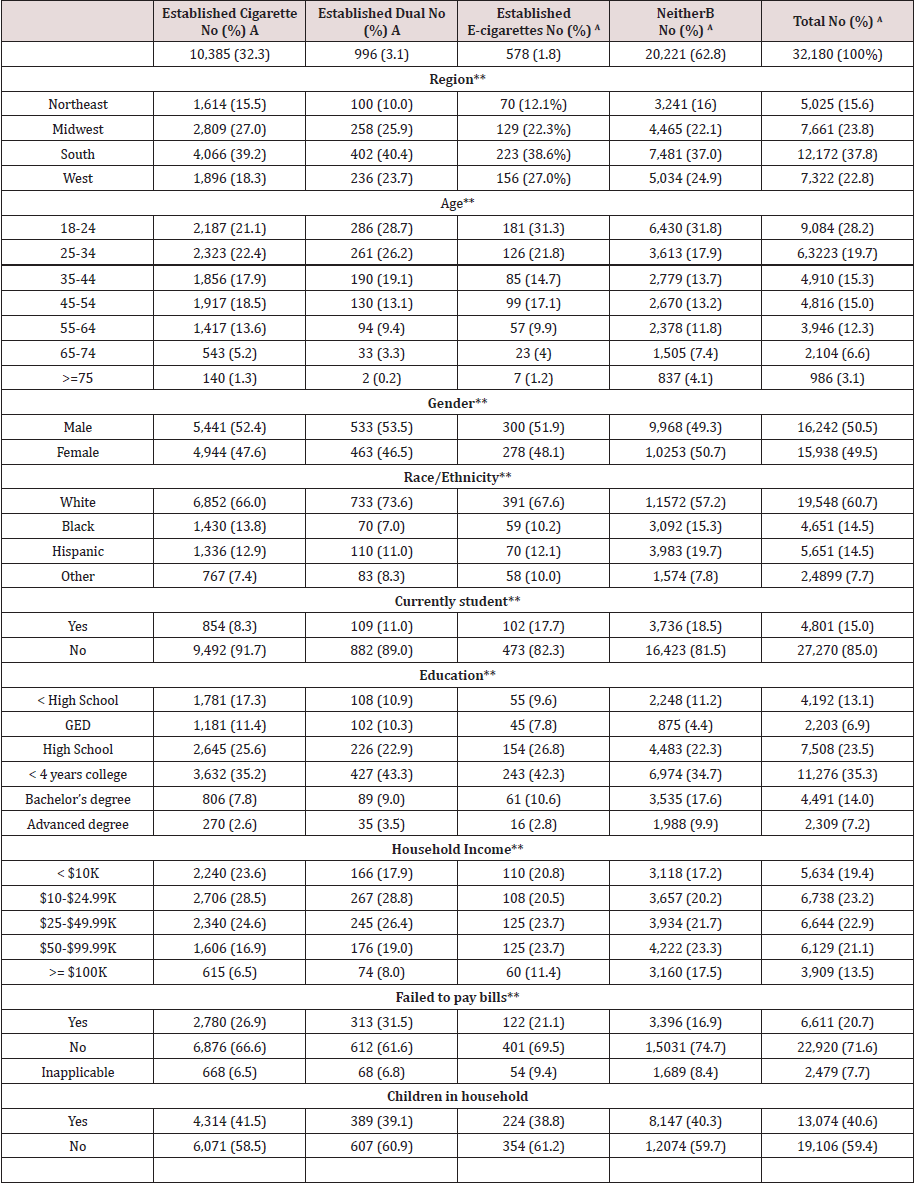

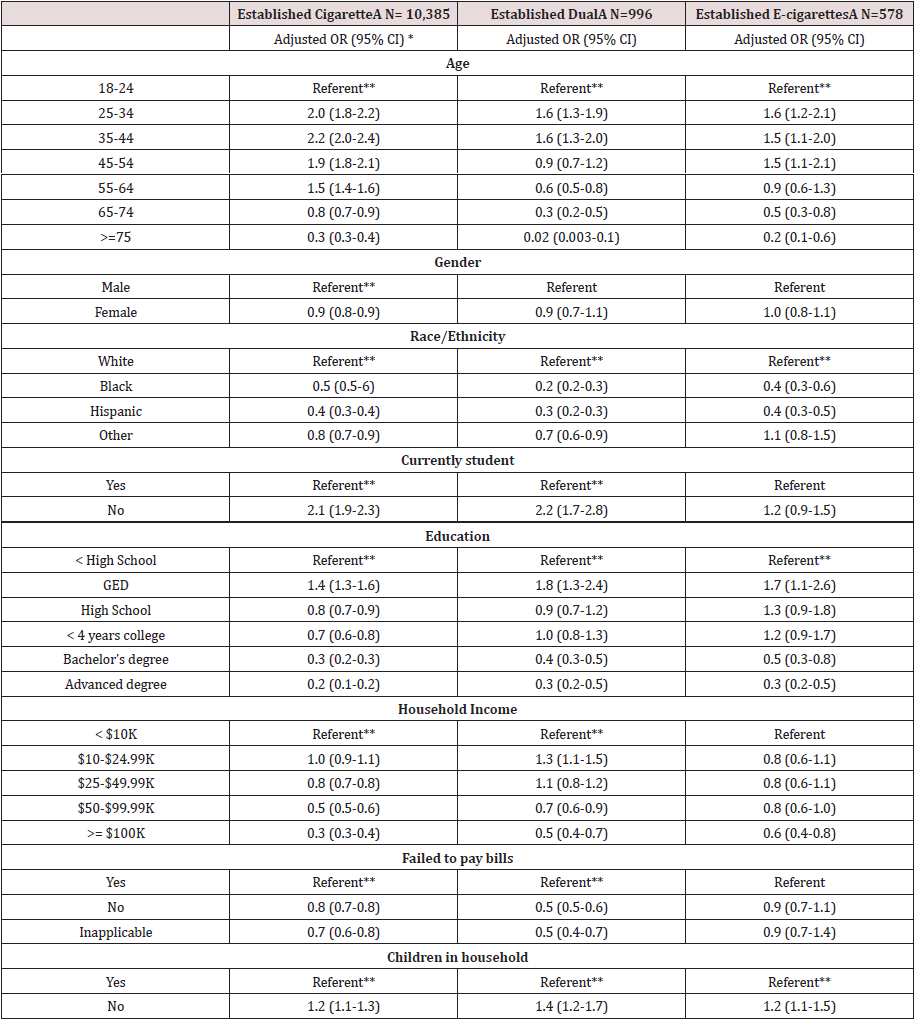

Among the 32,180 participants, 10,385 (32.3%) were established cigarette smokers, 578 (1.8%) were established e-cigarette users, 996 (3.1%) were dual users, and 20,221 (62%) participants were neither established cigarette or e-cigarette users (Table 1). Established e-cigarette users were younger, had higher educational levels and higher income than established cigarette users (Table 1). The sociodemographic characteristics of the study groups are shown in table 1. Interestingly, the highest proportion of established e-cigarette, cigarette, and dual users was in the South with an average of 40% of each group. The West came as the second most popular location for established e-cigarette users (27.0%) and the Midwest for established cigarette (27.0%) and dual users (25.9%). The order was reversed for the third common location, as the West was the third common location for established cigarette (27%) and dual users (25.9%), but for established e-cigarettes users (22.3%) the Midwest was the third common location. Among all groups the Northeast came fourth and lest regional location for established cigarette (15.5%), e-cigarette (12.1%), and dual users (10%), P < 0.001, (Table 1).The highest percentage of e-cigarette users (31.3%) and dual users (28.7%) was among 18-24 years of age. However, the highest percentage of established cigarette users was among the older age group of 25-34 years (22.4%), P < 0.001. Males contributed to a higher proportion of established cigarette (52.4%), e-cigarette (51.9%), and dual use (53.5%) compared to females, P < 0.001. Around two thirds of established cigarette (66.0%), e-cigarette users (67.6%), and around three quarters of dual established users (73.6%) were Whites i.e. significantly higher than among Blacks and Hispanics, P < 0.001 (Table 1). Significantly higher proportion of established e-cigarette users (17.7%) were students in comparison to established cigarette users (8.3%) and the dual user group (11.0%), P < 0.001. There was significant variation in the educational background among the study groups. For example, 9.6% of established e-cigarette users had less than high school, but higher proportion of established cigarette smokers (17.3%) had less than high school education, with dual users in between the two groups (10.9%), P < 0.001 (Table 1). Established e-cigarette users (11.4%) had higher proportion of > 100K income compared to established cigarette (6.5%) and dual users (8.0%), P < 0.001 (Table 1). There was no significant difference in having children (< 18 years) in the household between the four study groups with an average of 40% participants had children in their household. (Table 2) shows the results from three separate logistic regression models to estimate the adjusted odds Ratio (AOR) and accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI) for being established cigarette, or e-cigarette, or dual user compared to those who were not established users for both products. Compared with those who were not established cigarette or e-cigarette users, established cigarette users had higher odds of being White, male, between 24- 65 years, not a student and having less than high school education or GED, a lower household income, failed to pay some bills in the past 30 days, and no children in their household (Table 2). Established e-cigarette users had higher odds of being White, between 25 and 54 years and having less than four years college education, a lower income and no children in household compared with those who were not established users of e-cigarettes or cigarettes (Table 2). There was no difference by gender, student status or ability to pay bills. Established dual users, compared with those who were not established users of e-cigarettes or cigarettes, had higher odds of being White, between 25 to 44 years of age, not a student and having less than 4 years college education, with household income between $10,000-24,990 per year, failed to pay bills in the past 30 days, no children in the household (Table 2). There was no difference by gender.

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of established cigarette, established e-cigarette and established dual users, and other adults from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study first wave.

** P < 0.001

APercentages are by column. B This group represents those who were not established e-cigarette or cigarette users.

Table 2: Adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for being established e-cigarette, established cigarette, or established dual users among adults from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, first wave.

** P < 0.001, significance is shown for the whole variables.

AThe Adjusted Odds Ratio was estimated for each group in comparison to those who were not established e-cigarette or established

cigarette users.

Discussion

This study examined the sociodemographic characteristics of

established e-cigarette users; in addition to established cigarette

and established dual users from a representative sample of adults

in the US. Given e-cigarettes became popular few years ago, it

was expected that the prevalence of established cigarette use is

higher than established e-cigarette use as observed in our study;

32.3% Vs 1.8%. Adding the 3.1% dual users to each group, results

in a prevalence of 35.4% established cigarette users and 4.9%

for established e-cigarette users. The prevalence of established

cigarette use in the current study was higher than previously

reported in the US [26]. However, the current study established

e-cigarette use estimated prevalence is congruent with previous

estimate current use of e-cigarettes in the US [5,6]. Established use

of e-cigarettes differed significantly by region, age, race, gender,

educational background, annual household income, failure to pay

bills in the past 30 days compared to established cigarette, dual

users and others who were not established users for both products.

Previous research reported that the prevalence of e-cigarettes use

in the Mississippi was higher than the average estimate in the US

[23,27]. This supports our finding of the highest rates of established

e-cigarette, cigarette, and dual use in the South. Also, e-cigarettes

advertisement target males and females of younger age groups

[17,28], which might explain the higher proportion of established e-cigarettes being between the age of 18-24 years with no significant

gender difference, unlike established cigarette use which was more

likely among older age group and males. The adjusted odds ratio

from logistic regression models showed that the three groups of

established e-cigarette, established cigarette, and established dual

users were more likely to be White, young to middle age, with lower

education levels, and had no children in the household compared

to those who were not established e-cigarette or cigarette use

among the PATH study participants. The racial/ethnic distribution

is consistent with previous research that showed Latino and Black

are less likely to use tobacco products compared to Whites.1&18

Unlike established cigarette use, there was no significant difference

in e-cigarette use by gender, being student, household income, and

failure to pay bills. Historically, cigarette use was first adapted by

individuals from higher economic levels, who gradually abandoned

cigarettes due to its negative health effects after the publications

of studies such as the British medical doctors by 1950s [29, 30].

Therefore, cigarette use in the modern era became more common

among less affluent and less educated individuals as observed in

our study. The lack of certainty on adverse health effects associated

with e-cigarette use30 might explain the lack of economic difference

among its users compared to no users and the higher educational

attainment levels compared to cigarette users. Notably another

national survey reported higher prevalence of past 30 days use of

e-cigarettes among males, those between 18-24 years in age, those

of lower income [32]. The different finding in this study in respect

to gender and income might be attributed to using “established

use” of e-cigarettes rather than the past 30 days use and/or the

fact tobacco users was oversampled in the current study, which

allowed higher power to describe and assess the characteristics

associated with tobacco use. Also, the mentioned study examined

the prevalence only. The current study findings are based on the

adjusted odds ratio (to the reference population: those who were

not established users for e-cigarettes or cigarettes) enabled us

to better characterize e-cigarette users in comparison to the US

general adult population.

Most of the established e-cigarette users reported dual

established use of cigarettes (3.1%) with around one third used

e-cigarettes alone (1.8%). This observation might be explained

by a two-way association between e-cigarettes and cigarette use

as reported elsewhere [13]. In other words, e-cigarettes might

be a gateway for cigarette use and vice versa. Therefore, the

majority of the established e-cigarette users were in the dual use

phase. Interestingly, a published study reported that exposure to

e-cigarette marketing is not just associated with higher likelihood

to use e-cigarettes, but it is also associated with higher risk to use

various tobacco products [32]. Another possible explanation is

that established e-cigarette users are using e-cigarettes in places

where they cannot use cigarettes due to public bans or to aid them

in quitting.16-18 The current study was based on cross-sectional

survey. Therefore, we could not examine such possibilities to

suggest a conclusive explanation. E-cigarette use is expanding for

many reasons including the widespread advertising, [30,33,34].

perception of being less harmful than cigarettes [7], relatively

lower cost and ease of accessibility at online and sale outlets [35].

However, e-cigarettes pose health threats directly through its

ingredients and possible accidents associated with its malfunction

[1,18]. More importantly, it can be a backdoor to bring never

smokers into tobacco use via its gateway effect increasing the risk

of those individuals to tobacco associated morbidity and mortality

[1,18].Therefore, it is essential to understand the characteristics for

established e-cigarettes users as in the current study. The reported

sociodemographic for established e-cigarette users might help public

health professionals, advocacy organizations, and policymakers to

tailor prevention and control programs. Future studies should also

examine the association between sociodemographic characteristics

and progression of e-cigarette use into other tobacco product use

and vice versa. Our findings have some potential limitations. Firstly,

the PATH study has self-reported information on e-cigarette and

cigarette use. Therefore, it might be subject to recall bias and social

desirability bias [36], however, the consistency of our results with

other national surveys [5,6]. cross validates our results. Secondly,

the PATH study is a cross-sectional survey so we were unable to

assess the association between sociodemographic characteristics

and shift between e-cigarette and cigarette use and causality cannot

be assessed. On the other hand, the study has some strengths. For

example, the over sampling of tobacco users in the PATH study

might allowed higher power to describe their characteristics.

Also, the sample was drawn from the 50 states and the District of

Columbia, therefore the results can be generalized to adults in the

US. We used the definition of established e-cigarette and cigarette

users and this allowed better characterization for both products

established, and habitual users compared with other research that

focus on ever or past 30 days use that might reflect occasional or

experimental use.

Conclusion

Most of established e-cigarette users were established cigarette users too. Established e-cigarette and established cigarette users shared some characteristics; both groups were more likely to be living in the South of the US, White, younger, less educated, and have no children at their household. Established cigarette users had some characteristics, which were not shared by established e-cigarettes; they were more likely to be males, have a lower income and failed to pay bills in the past three days. However, established e-cigarette use was not significantly different among both genders and by household income. The observed characterization for established e-cigarette/cigarette users in the current study warrants further research to assess their association with progression into other tobacco use. Such new characteristics might be taken into account in prevention and control program to address a new group that might be at risk of tobacco use.

References

- Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA (2013) Background paper on e-cigarettes (electronic nicotine delivery systems). Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco.

- Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Deeming Tobacco Products to Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Restrictions on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products. Final rule. Fed Regist 81(90): 28973-29106.

- Hajek P, Etter JF, Benowitz N, Eissenberg T, McRobbie H SO (2014) Electronic cigarettes: Review of Use, Content, Safety, Effects on Smokers and Potential for Harm and Benefit. Addiction. 109(11): 1801-1810.

- King BA, Patel R, Nguyen KH, Dube SR (2015) Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010-2013. Nicotine Tob Res 17(2): 219-227.

- Caraballo RS, Jamal A, Nguyen KH, Kuiper NM, Arrazola RA (2016) Electronic Nicotine Delivery System Use Among U.S. Adults, 2014. Am J Prev Med 50(2): 226-229.

- Bao W, Xu G, Lu J, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB (2018) Changes in Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults in the United States, 2014-2016. JAMA 319(19): 2039-2041.

- Grana RA, Ling PM (2014) “Smoking revolution”: A content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med 46(4): 395-403.

- Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, Kosmider L, Sobczak A, et al. (2014) Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 23(2): 133-139.

- Dinakar C, O'Connor GT (2016) The Health Effects of Electronic Cigarettes. N Engl J Med 375(14): 1372-1381.

- Qasim H, Karim ZA, Rivera JO, Khasawneh FT, Alshbool FZ (2017) Impact of Electronic Cigarettes on the Cardiovascular System. J Am Heart Assoc 6(9): e006353.

- McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hartmann-Boyce J, Peter Hajek (2014) Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12): CD010216.

- Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, Fine MJ, Sargent JD (2015) Progression to Traditional Cigarette Smoking After Electronic Cigarette Use Among US Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Pediatr 169(11): 1018-1023.

- Auf R, Trepka MJ, Selim M, Ben Taleb Z, De La Rosa M, et al. (2019) E-cigarette use is associated with other tobacco use among US adolescents. Int J Public Health 64(1): 125-134.

- Furlow B (2015) US Government Warns Against Long-Term Dual Use of Conventional and E-Cigarettes. Lancet Respir Med 3(5): 345.

- Dockrell M, Morrison R, Bauld L, Ann McNeill (2013) E-cigarettes: prevalence and attitudes in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob Res 15(10): 1737-1744.

- Rutten LJF, Blake KD, Agunwamba AA,Rachel A Grana, Patrick M Wilson, et al. (2015) Use of e-cigarettes among current smokers: associations among reasons for use, quit intentions, and current tobacco use. Nicotine Tob Res 17(10): 1228-1234.

- Auf R, Trepka MJ, Cano MA, De La Rosa M, Selim M, et al. (2016) Electronic cigarettes: the renormalization of nicotine use. BMJ 352: i425.

- Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA (2014) E-cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation 129(19): 1972-1986.

- Doll R, Peto R (1978) Cigarette smoking and bronchial carcinoma: dose and time relationships among regular smokers and lifelong non-smokers. J Epidemiol Community Health 32(4): 303-313.

- Lippert AM (2014) Do Adolescent Smokers Use E-Cigarettes to Help Them Quit? The Sociodemographic Correlates and Cessation Motivations of US Adolescent E-Cigarette Use. Am J Health Promot 29(6): 374-379.

- Dutra LM, Glantz SA (2014) Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among us adolescents: A cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr 168(7): 610-617.

- Alcalá HE, Albert SL, Ortega AN (2016) E-cigarette use and disparities by race, citizenship status and language among adolescents. Addict Behav 57: 30-34.

- Mendy VL, Vargas R, Cannon-Smith G, Payton M, Byambaa E, et al. (2017) Electronic Cigarette Use among Mississippi Adults, 2015. Addict 2017: 5931736.

- Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Nicolette Borek, Elizabeth Lambert, et al. (2017) Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH). Tob Control 26(4): 371-378.

- (2019) PATH Study Public Use Files: User Guide.

- Jamal A, Phillips E, Gentzke AS, David M Homa, Stephen D Babb, et al. (2018) Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67(2): 53-59.

- Schoenborn CA, Gindi RM (2015) Electronic cigarette use among adults: United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief 217: 1-8.

- Rehab Auf, Mary Jo Trepka, Moaz Selim, Ziyad Ben Taleb, Mario De La Rosa, et al. (2017) E-cigarette marketing exposure and combustible tobacco use among adolescents in the United States. Addict Behav 78: 74-79

- Doll R, Hill AB (1950) Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. Br Med J 2(4682): 739-748.

- Doll R, Hill AB (1954) The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. Br Med J 1(4877): 1451-1455.

- Tan ASL, Bigman CA (2014) E-cigarette awareness and perceived harmfulness: Prevalence and associations with smoking-cessation outcomes. Amer J Prev Med 47(2): 141-149.

- yamlal G, Jamal A, King BA, Mazurek JM (2016) Electronic cigarette use among working adults - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65(22): 557-561.

- Jennifer C Duke, Youn O Lee, Annice E Kim, Kimberly A Watson, Kristin Y Arnold, et al. (2014) Exposure to electronic cigarette television advertisements among youth and young adults. Pediatrics 134(1): e29-36.

- Huang J, Tauras J, and Chaloupka FJ (2014) The impact of price and tobacco control policies on the demand for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tob Control 23(suppl 3): iii41-47.

- Bold KW, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S (2016) Reasons for trying e-cigarettes and risk of continued use. Pediatrics 138(3): e20160895.

- Hayes DK, Fan AZ, Smith RA, Bombard JM (2011) Trends in selected chronic conditions and behavioral risk factors among women of reproductive age, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2001–2009. Preventing Chronic Disease 8(6): A120.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...