Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6628

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6628)

Nutritional Status and Cognitive Function of Newly Diagnosed School-Aged Children with Epilepsy Seen at a Paediatric Neurology Clinic in Benin City, Nigeria Volume 6 - Issue 3

Paul Ehiabhi Ikhurionan1, Ughiemosomhi Pamela Ikhurionan2 and Irelosen Kingsley Akhimienho3*

- 1Department of Child Health, University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

- 2Department of Family Medicine, University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

- 3Department of Paediatrics, Edo state University Uzairue, Nigeria

Received: June 29, 2022; Published: July 15, 2022

Corresponding author: Irelosen Kingsley Akhimienho, Department of Paediatrics, Edo state University Uzairue, Nigeria

DOI: 10.32474/OJNBD.2022.06.000237

Abstract

In children with epilepsy, nutritional problem of varying degree and cognitive problems are common co-morbidities. There is evidence that under-malnutrition can impair cognitive development in children. However, the association between nutritional status and cognitive capacity of CWE has not been extensively studied in Nigerian children. This study, therefore, sought to evaluate the association between nutritional status and cognitive performance of school age children with epilepsy. We carried out cross-sectional study of 60 newly-diagnosed school-aged CWE seen at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital. The Wechsler intelligence scale for children (Fourth edition) and the Iron Psychology computerized test battery were used to assess intelligence, attentional ability, memory and psychomotor function. We analyzed the relationship between anthropometric measures of nutritional status and cognitive scores. Associations were significant at p<0.05.

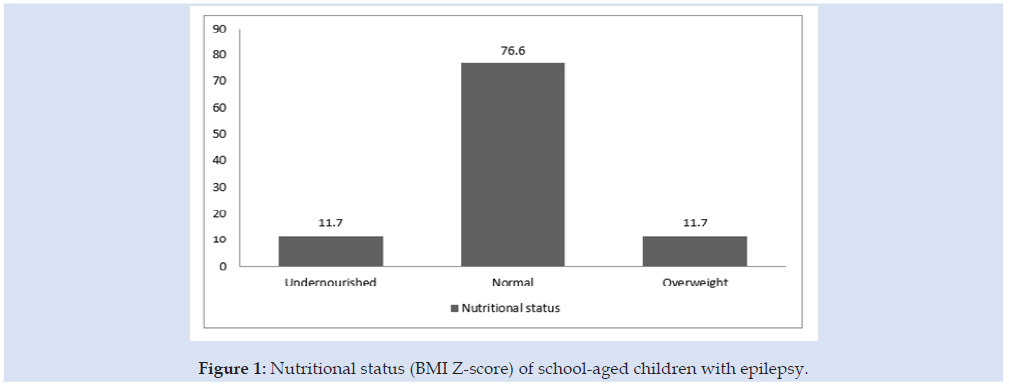

The children’s age ranged from 6.3years to 12.0 years with a mean age was 9.45 years (SD 1.88 years). Thirty-two (53.3%) were boys, and 29 (48.3%) were from the lower socio-economic class. Most of the participants had generalized epilepsy (80%) and developed their first seizure after their fifth birthday (56.6%). Seven (11.7%) of the study participants were under-nourished and seven (11.7%) had overweight. None of the participants was wasted or stunted. Malnourished children had significantly poorer performance than the well-nourished CWE in test of Attention (F-4.927, p-0.031), verbal memory (F-6.618, p-0.013) and Fine motor control (F-11.764, p-0.001). Overweight children had comparable scores as children with normal nutritional status. In conclusion, about one in ten school-aged CWE have undernutrition and a similar proportion has overweight. Children with undernutrition have impaired attention, verbal memory and fine-motor control in comparison to their well-nourished counterparts. Overweight school-age CWE have similar cognitive performance as those with normal nutritional status.

Keywords: Nutritional Status; Cognition; School-Age;, Children; Epilepsy

Introduction

Malnutrition in children is a major public health challenges in low- and middle-income countries today [1]. Approximately 200 million children worldwide do not reach their developmental potential as a result of under-nutrition and poverty [2]. Of these, more than 170 million children are stunted and 52 million wasted worldwide.2 Studies from Nigeria report undernutrition in 9.9 – 20% and stunting in 1.4 – 41.6% of school age children with significant rural-urban variation [3-5]. Recent reports also suggest that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescence is increasing [6]. A study from Nigeria have documented prevalence of overweight and obesity in school age children to be 6.6% and 8.9% respectively [7]. The school age is a period of significant physical and cognitive changes and strain.8 This period is characterized by increased activity and the development of physical and cognitive functions.8 Generally, school age children require ample nourishment and physical activity for healthy brain growth, optimal learning, and ultimately, good academic performance [8]. There is evidence that under-malnutrition can impair cognitive development in children [9]. This is because malnourished children lack essential micronutrients which are very pivotal in early childhood brain development.9 Fink and colleagues investigated the effects of growth during late-childhood and early-adolescence period on schooling and developmental outcomes. They found that among children stunted at age eight years of age, those who remained stunted at 15 years had greater deficit in cognitive scores than their peers whose growth deficit had corrected with adequate feeding [10]. On the other side of the spectrum, problems with attention switching tasks have also been reported amongst children with obesity [11].

In children with epilepsy, nutritional problem of varying degree and cognitive problems are common co-morbidities [12]. It has been suggested that malnutrition may be partly responsible for the high prevalence of epilepsy and cognitive problems among children in developing countries [12]. Experimental models have shown some association between malnutrition and cognitive problems in animals with experimentally induced seizures [13]. However, this association have not been extensively studied in children with epilepsy. This study, therefore, sought to evaluate the association between nutritional status and cognitive performance of school age children with epilepsy. We hypothesized that the presence of under-nutritional in school age children with epilepsy would result in poorer cognitive performance in these children compared to well-nourished children with epilepsy.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a hospital-based analytical cross-sectional study.

Participants

Subjects included school age children with epilepsy (CWE) who presented at the Paediatric Neurology Clinic of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH). Participants were recruited at first presentation at the Paediatric Neurology Clinic. The aim of the study and procedures involved were explained in detail to them and/or their parents/carers. Thereafter informed consent was gotten from the parents/care givers while the participants gave accent. Epilepsy was classified based on the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) criteria [14]. A researcher-administered proforma was used to obtain information including age, gender, parent’s occupation, parent’s level of education, age at onset of epilepsy, frequency of seizures and type of seizures.

Subjects were selected based on the following criteria:

a) age 6 – 12 years,

b) absence of known causes of seizures and

c) absence of other known neurologic diagnosis.

Procedures and Cognitive Assessment

Anthropometric measurements were taken by the same operator, according to conventional criteria and measuring procedures [15]. For weight measurement, the scale was placed on a flat, hard, even surface, child was in minimum clothing during weighing, removed his/her shoes, and the weight was recorded to the nearest 100 Grams. The height was measured by using a standiometer. The child was standing without shoes with feet parallel on an even platform stretching fullest, arms hanging on the sides, and buttocks and heels touching the rod, the head held erect with lower border of the eye orbit in the same horizontal plane as the external canal of the ear (Frankfort plane) and the head piece lowered to touch the top of the head. The Height (cm) was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. Intellectual function was assessed using the Wechsler’s intelligence scale for children fourth edition (WISC IV) [16] while attention, memory, reaction times and fine motor control were assessed using the Iron Psychology computerized test battery [17].

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained were analyzed using Statistical Package for Scientific Solutions (SPSS) version 21.0 (IBM SPSS version 21.0). The primary outcome (cognitive scores) were presented using means (± standard deviation). The categorical variables such as gender and socioeconomic status were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Socioeconomic status of participants was assessed using the father’s occupation and mother’s educational level as described by Olusanya et al. [18] Student t-test was used to compare means of continuous variables like age and FSIQ scores. Recognizing that cognitive development could be influenced by socio-economic class we controlled for the child’s social class. The level of significance was set at p<0.05 and confidence level at 95%.

Ethic

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of UBTH.

Result

Sociodemographic and Seizure Characteristics of Study Participants

Sixty school aged children who were recently diagnosed with epilepsy were recruited for this study. The children’s age ranged from 6.3 years to 12.0 years with a mean age was 9.45 years (standard deviation of 1.88 years). Thirty-two (53.3%) were boys, and 29 (48.3%) were from the lower socio-economic class. Most of the participants had generalized epilepsy (80%) and developed their first seizure after their fifth birthday (56.6%). The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Nutritional Status of Participants

Seven (11.7%) of the study participants had BMI z-score less than -2Z and seven (11.7%) had BMI z-scores above +2Z. None of the participants was wasted but 10 (16.7%) had WAZ scores greater than +2Z. All participants had HAZ scores greater than -2Z scores Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2: Comparison of cognitive performance between normal and undernourished school-age children with epilepsy.

*Significant at p< 0.05

Mean Cognitive Scores of Study Sample

The mean scores of the tests were 84.8 (± 14.6) for general intelligence (WISC-IV), 533.2 (± 97.0) for attention (Fepsy-Bch), 75.98 (+ 23.98) for verbal memory (word recognition accuracy), 29.37 (+ 7.21) for visuo-spatial memory (figural recognition accuracy), 516.52 (+ 145.74) for auditory reaction (Fepsy) and 437.02 ± 124.56 for visual reaction (Fepsy).

Association Between Nutritional Status and Cognitive Performance of Children with Epilepsy

Table 3: Comparison of cognitive performance between normal and overweight school-age children with epilepsy.

*Significant at p< 0.05.

Malnourished children had poorer performance than the well-nourished CWE in all test performed. However, significant difference in performance was observed for test of attention (F- 4.927, p-0.031), verbal memory (F-6.618, p-0.013) and fine motor control (F-11.764, p-0.001). This is shown in Table 2. Overweight children had comparable scores as children with normal nutritional status. They however had significantly higher FSIQ scores (F-8.798, p-0.005) Table 3.

Discussion

More than one in 10 children with epilepsy was undernourished. Overweight was present in one-tenth of the sample population. Under-nourished CWE show significant impairment in test of attention, verbal memory and fine motor control compared to their well-nourished counterparts. On the contrary, overweight children had similar performance as well-nourished children in all tests of cognition assessed except for general intelligence where they fared better than well-nourished children. In the current study, undernutrition was present in more than one in 10 (11.7%) school age CWE. This was similar to the observation of Tekin et al. (13.8%) among Turkish children with epilepsy [19]. It was, however, lower than 22.1% reported by Crepin and colleagues (2007) in Djidja, Benin [20]. The difference in prevalence may be because our study was among children in urban locale whereas the study in Djidja was among rural children with epilepsy. Also, the present study involved children with idiopathic epilepsy only while their study included all children with epilepsy. It is well known that symptomatic epilepsy and epileptic encephalopathies may be associated with other comorbidities that can impact on nutrition including cerebral palsy and feeding problems [21]. The prevalence reported in our study, is also similar to what was reported among non-epileptic schoolaged children in Abakiliki, South-Eastern Nigeria (9.9%), [4] and Eze et al. in Enugu(9.3%) [22]. The similarity of the prevalence of undernutrition in CWE and the general population suggests that idiopathic epilepsy may not significantly affect growth and nutrition in school age children [23].

The prevalence of overweight among school-age children with epilepsy in this study was 11.7%. This prevalence is comparable with the observation of Prabowo et al in Indonesia (14.7%) [24]. Previous studies have attributed overweight and obesity in CWE to adverse effect of prolonged use of antiepileptic drugs [25]. Our study cohort, however, were newly diagnosed CWE yet to commence AEDs. It is likely that overweight and Obesity in CWE is also a result of a sedentary lifestyle due restricted play and activities imposed on them by their parents and care-givers. The prevalence of overweight in the present study was lower than the 18.7% reported by Daniels et al amongst paediatric patients in Southwestern Ohio [26]. In their study, almost 4 in 10 children had obesity or Overweight. The lower prevalence among our study sample may be explained by the low economic status of our country in comparison to the American population.

Concerning the association between nutritional status and cognitive performance, school-aged CWE who were undernourished performed more poorly than their well-nourished counterparts in test of attention, verbal memory and fine motor control. Similar findings have been documented in other studies [27,28]. Previous authors have suggested that the prefrontal cortex which is responsible for attention and memory function might be the most vulnerable to under-nutrition. The adverse effects of undernutrition on cognitive development could be related to the delay in the maturation of certain processes like myelination and reduced overall development of dendritic arborization of the developing brain [29]. Overweight children on the other hand, did not differ significantly in cognitive test scores from their counterparts with normal BMI. Problems of attention and executive functions have been linked with childhood obesity and overweight by a previous study [30]. This study however, like ours did not find significant effect of obesity and overweight on intelligence and memory function in children. Further studies would be needed to further explore the influence of obesity and overweight on cognition in both children with epilepsy and those without epilepsy.

The findings of the current study have implication for learning and educational outcomes in children with epilepsy. It may be necessary to reinforce school feeding programs especially in CWE and encourage healthy eating among this population. Similarly, continuous growth monitoring into the schools and referrals where necessary would help to identify children with faltering nutritional status. One limitation to our study is that a one-time anthropometry measurement was done in study cohort. A longitudinal design might have been demonstrated a trend and establish changes in cognitive performance with nutritional status.

Conclusion

In conclusion, most school-age children with epilepsy in Benin City have normal nutritional status. About one in ten have undernutrition and a similar proportion has overweight. Children with undernutrition have impaired attention, verbal memory and fine-motor control in comparison to their well-nourished counterparts. Overweight school-age CWE have similar cognitive performance as those with normal nutritional status.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Dr Koleoso for assisting with intelligence testing in study participants.

References

- Black RE, Victoria CG, Walker SP, Bhenta A, Christain P, et al. (2013) Maternal and child under nutrition an overweight in low income an middle income countries. Lancet 328(9890): 427-451.

- World bank. Early Childhood Development.

- Ayogu RNB, Afiaenyi IC, Madukwe EU, Elizabeth A Udenta (2018) Prevalence and predictors of under-nutrition among school children in a rural South-eastern Nigerian community: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 18(1): 587.

- Umeokonkwo AA, Ibekwe MU, Umeokonkwo CW, Okeke CO (2020) Nutritional Status of School Aged Children in Abakaliki metropolis. Ebonyi State Nigeria. BMC pediatrics 20(10): 114-122.

- Ene Obong H, Ibeanu V, Onuoha N, Ejekwu A (2012) Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and thinness among urban school-aged children and adolescents in southern Nigeria. Food Nutr Bull 33(4): 242-250.

- Akhimienho KI, Nyaong E, Adesina FB (2021) Adolescent Obesity. An emerging public health crisis in an urban city in south-south Nigeria. Annals of clinical and biomedical research 2(2): 148.

- Adeniyi OF, Fagbenro GT, Olotona FA (2019) Overweight and Obesity Among School-aged Children a Maternal Preventive Practices against Childhood Obesity in Select Local Government Areas of Lagos, South-West, Nigeria. Int J MCH AIDS 8(1): 70-83.

- Evans D, Borriello GA, Field AP (2019) A review of the Academic and Psychosocial Impact of the Transition to Secondary Education. Front Psychol 9(1482): 1-18.

- Roberts M, Tolar Peterson T, Reynolds A, Wall C, Reeds N, et al. (2022) The Effects of Nutritional Intervention on the Cognitive development of Preschool-age children. A systematic Review. Nutrients 14(3): 532.

- Fink G, Rockers PC (2014) Childhood growth, schooling, and cognitive development: Further evidence from the Young Lives study. Am J Clin Nutr 100(1): 182-188.

- Crookston BT, Forste R, McClellan C, Georgiadis A, Heaton TB (2014) Factors associated with cognitive achievement in late childhood and adolescence: the Young Lives cohort study of children in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. BMC Pediatr 14: 253.

- Sanou AS, Diallo AH, Holding P, et al. (2018) Association between stunting and neuro-psychological outcomes among children in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 12(1): 1-10.

- Escolano Margrit MV, Campoy C (2018) Nutrition and the Developing Brain. Swaiman’s Paediatric Neurology Principles and Practice. Elsevier pp. 383-389.

- Speccio N, Wirrell C, Schoffr IE, Nobbot R, Ribay K, et al. (2022) International League Against Epilepsy Classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in childhood: Position paper by the ILAE Task Force on Neurology and Definitions. Epilepsia 63(6): 1398-1442.

- World Health Organisation (1995) Physical Station: The use and interpretation of anthropometry; a report of a WHO expert committee series no 85, Geneva, USA.

- Wechsler D (2003) Administration and Scoring Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th ), The Psychological Corporation.

- Alpherts WCJ, Aldenkamp AP (1990) Computerized neuropsychological assessment of cognitive function in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 31(suppl 4): 35-40.

- Olusanya O, Okpere E, Ezimokai M (1985) The importance of social class in voluntary fertility control in a developing country. West Afr J Med 4: 205-212.

- Tekin H, Tekgül H, Yılmaz S, Arslangiray D, Reyhan H, et al. (2018) Prevalence and severity of malnutrition in pediatric neurology outpatients with respect to underlying diagnosis and comorbid nutrition and feeding related problems. Turk J Pediatr 60(6): 709-717.

- Crepin S, Houinato D, Nawana B, Avode GD, Preux PM, et al. (2007) Link between epilepsy and malnutrition in a rural area of Benin. Epilepsia 48(10): 1926-1933.

- Pavon P, Guilizia C, Le Pira A, Greco F, Parisi P, Do Cara G, et al. (2021) Cerebral Palsy and Epilepsy in Children. Clinical Perspectives on a Common Co-morbidity. Children (Basel) 8(1): 16-19.

- Eze JN, Oguonu T, Ojunnaka NC, Ibe BC (2017) Physical Growth and Nutritional Status Assessment of school children in Enugu, Nigreia. Niger J Chin Pract 20(1): 64-70.

- Nunes ML. Teixeria GC, Febris I, Gonclaves A (1999) Evolution of the Nutritional Status in Institutionalize Children and its Relationship to the Development of Epilepsy. Nuti Neurosci 2(3): 139-143.

- Prabowo CA, Suwarba IN, Mahalini DS (2020) The Nutritional Profile Among Children with Epilepsy at Sanglah Hospital. Clinical Neurology and Neuroscience 4(4): 92-97.

- Teng Y, Cheng H, Hung Y (2009) Long term antiepileptic drug therapy contributes to the acceleration of atherosclerosis. Epilepsia 50(6): 1579-1586.

- Daniels ZS, Nick TG, Liu C, Casseydy A, Glauser TA (2009) Obesity is a common comorbidity for paediatric patients with untreated newly diagnosed epilepsy. Neurology 73(9): 658-664.

- Riggs NR, Huh J, Chou CP, Spruijt Metz D, Pentz MA (2012) Executive functions and latent classes of childhood obesity risk. J Behav Med 35(6): 642-650.

- Riggs NR, Spruitz- Metz D, Chou CP,Pentz MA (2012) Relationship between executive function and lifetime substance use and obesity related behaviours in fourth grade youth. Child Neuropsychol 18(1): 1-11.

- Kar BR, Rao SL, Chandramouli BA (2008) Cognitive development in children with chronic protein energy malnutrition. Behav Brain Funct 24: 31.

- Cserjési R, Molnár D, Luminet O, Lénárd L (2007) Is there any relationship between obesity and mental flexibility in children?. Appetite 49(3): 675-678.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...