Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6628

Review Article(ISSN: 2637-6628)

Mental Illness at Work – Forms of Managerial Intervention Volume 5 - Issue 3

Markus Fischl*

- Social Psychiatric Outpatient Center, Neuromed Campus, Kepler University Hospital Linz, Austria

Received:March 15, 2021 Published:March 22, 2021

Corresponding author: Markus Fischl, Social Psychiatric Outpatient Center, Neuromed Campus, Kepler University Hospital Linz, Austria

DOI: 10.32474/OJNBD.2021.05.000216

Abstract

Mental illness is still a gray area at most Austrian companies and remains associated with various stigmas, even though nearly one in every 10 days of sick leave is due to mental illness. This causes the phenomenon of presenteeism, and it also results in a considerable cost for the business and the economy as well as losses in productivity. Numbers of sick days taken due to mental illness are growing significantly, and this trend can only be counteracted with a corporate culture of openness, education, and destigmatization, and by taking the appropriate measures in all aspects of prevention. Both companies and politicians are therefore called upon to become proactive by creating the appropriate framework.

Keywords: Mental Illness; Early Intervention; Presenteeism; Awareness; Destigmatization; Workplace

Introduction

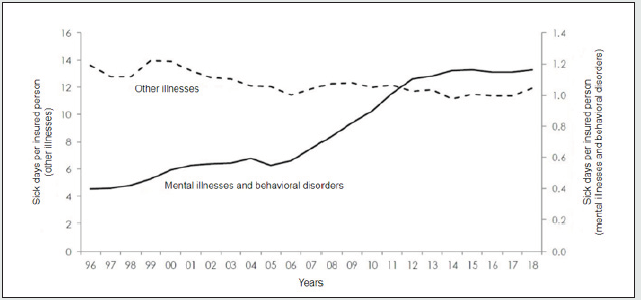

Since the mid-1990s, statistics produced by the Austrian association of social insurance providers have shown a clear trend with a high growth rate: While the number of absences caused by other significant illness groups such as injuries, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory, muscular and skeletal disease has declined slightly, the number of sick days caused by mental illness has almost tripled over the same period (Figure 1). However, the actual significance of these mental health problems for the overall health of the labor force is difficult to estimate on the basis of these statistics. It is clear that over this period doctors have been more prepared to attribute health problems to mental causes. But it is safe to assume that numerous cases of sick leave, some of which are caused by poor mental health, continue to be attributed to other illness groups due to the symptoms present when the diagnosis is made. For example, complaints such as allergies, stomach ache, and circulation problems can be caused by stress and psychological strain without the resulting cases of sick leave being attributed to mental health problems.

Figure 1: Development of mental illness (source: Austrian association of social insurance providers).

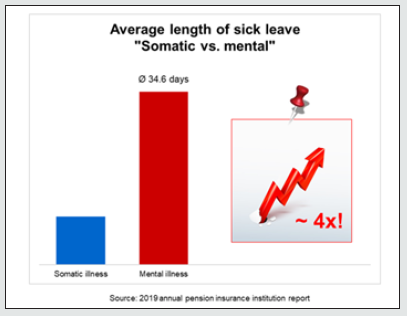

The major significance of mental stress and illness in the working environment can be confirmed with other sources. Studies have repeatedly shown that depression, stress, and anxiety are among the health problems most frequently cited by employees in relation to their job. The OECD estimates that in its member states between 20 and 25% of the working-age population are affected by clinical mental health issues. Around 5% have serious mental disorders, while the remaining 15% have minor to moderate disorders [1]. The average duration of sick leave taken by individual employees as a result of mental illness is 34.6 days per incident – nearly four times as long as for somatic illnesses, which on average across all illness groups result in just 9.6 sick days per incident (Figure 2) [2]. But how can this huge increase in illnesses and sick leave be explained? Has mental stress at work increased in recent years? Have employees become less resilient? Is it that we can now talk more openly about mental disorders, so that we are finally seeing the true extent of the burden of disease? Are we better at diagnosing mental health problems than we were before?. All these reasons play their part to a certain extent.

Spiraling Costs

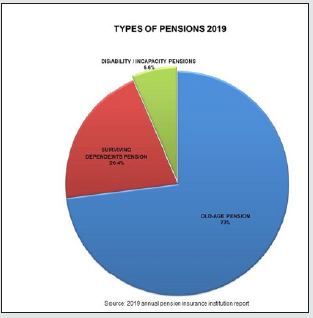

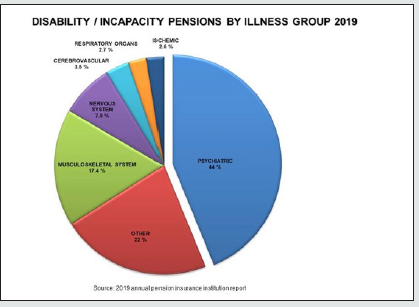

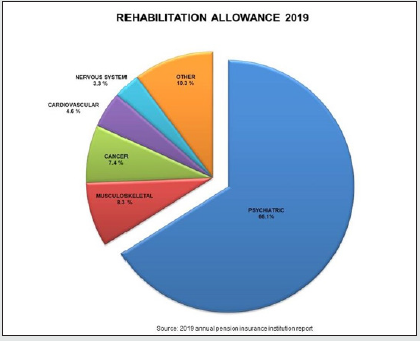

As the data shown above make clear, psychiatric illness has become a major cost factor for businesses and the Austrian economy as a whole. And the pension statistics also reveal some extremely alarming figures: the 2019 annual report produced by the Austrian pension insurance institution shows that 6.6% of working-age people in Austria are disabled or unable to work. The largest cause of early retirement is mental illness (43.8%), a long way clear of the next-highest causes – musculoskeletal conditions (17.4%) and nervous system disorders (7.9%) – while 66.1% of people claiming rehabilitation allowance were doing so as a result of mental illness [3] (Figures 3-5). Taking into account the fact that disorders are frequently under-diagnosed and misdiagnosed for a variety of reasons, the increase in absences from work as a result of mental health problems is even bigger than shown by the statistics.

Presenteeism and Absenteeism

In addition to longer periods of absence and incapacity for work, there is the problem of reduced productivity and performance from those employees who frequently come into work when they are ill. This phenomenon is known as “presenteeism”. Employees suffering from depression, for example, make more mistakes at work and do not work as quickly as their healthy colleagues. Typical symptoms of this illness, such as impaired concentration and ability to retain information, negatively impact performance, and sufferers also tend to withdraw socially from their working environment, which can add to the strain on the rest of their team. By contrast to presenteeism, there is the problem known as absenteeism, which refers to feigning illness when the person is in fact fully able to work. Presenteeism and absenteeism are also called “motivated absence”, and just like absences caused by health issues they have a harmful short and long-term impact both economically and socially. The 2018 Austrian workplace absence report, which focused on this issue, concluded that both absenteeism and presenteeism can be influenced by personality traits [see below], but also that workplace and organizational factors (such as corporate culture and leadership) and structural factors (such as workplace safety) play a role [4].

The 2018 Workplace Absence Report Identified the Following Primary Risk Factors for Presenteeism at a Personal Level

a) Problems setting personal boundaries

b) A strong feeling of loyalty towards managers and colleagues

c) A sense of obligation towards customers/clients

d) Work that can only be performed by the individual in question,

e.g. in the case of staff shortages or a high level of specialization.

e) A strong sense of camaraderie within teams, e.g. when working

on projects with tight deadlines [4].

The Report Identified the Following Risk Factors at an Organizational or Structural Level

a) Poor leadership and corporate culture, e.g. when there

is little respect, trust, or support between management and

employees, or when employees are suspected of not having genuine

reasons for absences,

b) High working demands with inadequate support [4].

In the workplace absence report, presenteeism and absenteeism were measured on the basis of self-reporting collected by surveys. The available survey data clearly show that they are issues of considerable importance for the Austrian economy. Data from the 2014 Austrian Health Survey, alongside analysis carried out by the Upper Austrian Chamber of Labour in its Work Climate Index and Employee Health Monitor for the period between 2008 and 2017, show that over the course of a year around half of Austrian employees display presenteeism [4].

Across All Sectors, those Who Displayed Presenteeism gave the Following Reasons

a) A sense of obligation towards colleagues (60%),

b) Lack of a substitute (33%)

c) Worry about work that would otherwise not be done (35%),

d) Fear of negative consequences (16%),

e) Either having themselves had previous problems at work

relating to sick leave or knowing that someone else at the

company/organization had these problems (around 15%).

However, the 2018 workplace absence report noted considerable differences between the sectors and the qualifying groups [4].

Economic Impact of Mental Illness in Austria and Europe

A report produced by the OECD and the European Commission (Health at a Glance: Europe 2018) revealed that mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety and alcohol/drug addiction affect more than one in six EU citizens. In addition to the impact on citizens’ wellbeing, the OECD estimates that the total cost is over 600 billion euros – or more than 4% of GDP – across the 28 EU countries. A large part of this cost can be attributed to lower employment rates and reduced productivity from people with mental illness (1.6% of GDP or 260 billion euros) and to higher social insurance spending (1.2% of GDP or 170 billion euros), while the rest is accounted for by direct spending on healthcare provision (1.3% of GDP or 190 billion euros) [5]. Millions of people would benefit from earlier diagnosis and treatment of mental illness. The study showed that in Austria the cost is 4.33% of GDP (thus amounting to 15 billion euros), somewhat higher than the European average [5]. The high cost of mental illness for patients, families, employers and the wider economy has also been highlighted by the British publication “Mental Health in the Workplace” [6]. It is therefore little surprise that improving mental health at work has become a key strategic focus. This increased interest has led to new reviews of the evidence base in relation to common mental disorders and to the introduction of policies aimed at boosting mental health and wellbeing in the workplace.

In particular, it has been argued that employers should provide safe and supportive working environments and improve work organization – though this can be difficult in practice. One reason is that mental illness continues to be viewed as an individual’s problem, with the associated stigma, and another is that people confronted with these problems in the workplace (e.g. senior managers, line managers, and HR specialists) often lack the necessary skills to handle them. In addition, access to professional occupational health services is frequently inadequate, especially for employees at SMEs [6].

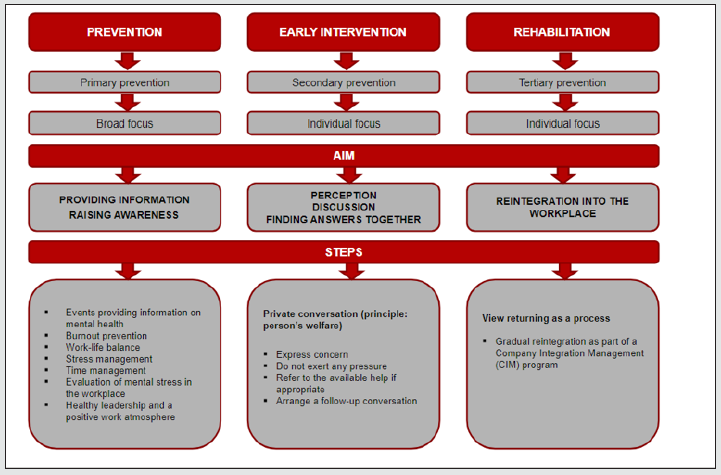

Managerial Measures to Combat Mental Illness

Effective prevention of mental disorders in employees can only be successful if it is adopted as a corporate goal and if a solution-oriented approach to improve mental health is agreed in consultation with all employees. A crucial aspect of this is companywide support in removing the taboo surrounding this issue, alongside the provision of information and guidance for managers and employees [7].

Destigmatization and Raising Awareness of Mental Illness

There remains a stigma around being mentally ill. Inadequate knowledge about mental illness and the associated stigmas have harmful consequences on the mental health of those affected.

There are three Main Forms of Stigma

a) Public stigmatization: Discrimination by work colleagues,

managers, and the population as a whole on the basis of

mental illness.

b) Self-stigmatization: The person affected internalizes these

negative perceptions.

c) Structural discrimination: Mental illness is not allocated the

same resources by health and pension insurance providers as

somatic illnesses.

Prejudices and stereotypes remain widespread: Those suffering from mental illness are considered dangerous, unpredictable, incurable, and even likely to display violent behavior. It is also incorrectly assumed that there is a clear boundary between being mentally healthy and mentally ill, when in fact, mental health is constantly in a state of flux. The preconception that those affected are at fault for their own suffering leads to a lack of understanding and can even cause hostile reactions, and those who are mentally ill are often treated with fear or simply avoided. On top of this, a vague (but very common) sense of “being normal” remains a barrier to opening up about mental health.

These Forms of Stigmatization have the Following Consequences

a) Those affected become withdrawn within their team,

b) They and their families suffer from a lower sense of self-worth,

c) They begin to feel guilt and shame,

d) They only begin psychiatric/psychotherapeutic therapy

belatedly or not at all, as they don’t want to be labeled as

“mentally ill” by undergoing this therapy,

e) In a worst case scenario, suicide is seen as the last and only

“way out”.

These factors make clear the importance of raising awareness of the nature and context of mental illness, particularly in a business environment [8].

Awareness Campaigns at Work

One of the key steps that can be taken to improve people’s basic understanding of this issue are awareness campaigns on the facts and figures, available treatments, and wider context surrounding mental illness in today’s workplace. These should aim to involve all employees, no matter where they are in the company hierarchy, and can for example be conducted through “Mental Health Awareness Days” or employee events.

It is Recommended that the Following Messages (Among Others) be Conveyed to Employees

a) One in three Austrians will suffer from mental illness at some

point in their life (“It can happen to anyone”).

b) Mental illness can be treated effectively.

c) Seeking professional help is no reason to feel ashamed (“the

sooner the better”).

d) There are treatments available and people to talk to in a

psychosocial network (“Where can I turn to if I need help?”).

There are lots of creative ways to design destigmatization campaigns using a variety of media. For example, the content can consist of videos of those affected (whether employees or senior managers) talking about their experience of mental illness and how they returned to work. The key message to convey is: “If only I’d done something about it earlier, I’d have made things a lot easier for myself!”. This testimony, alongside informational material and e-learning tools, can help improve general awareness of mental illness.

The Following were Identified as Essential Requirements for Good Work [9]

a. A secure job with a secure income (92%)

b. Meaningful, varied work (85%)

c. The social aspect of work (84%)

d. Health and safety (74%)

e. Scope for influence and freedom to act (71%)

f. Opportunities for development (66%)

g. High-quality management (66%)

The INQA Study Showed that in Many Sectors Work Conditions were No Better Than “Average”, Meaning that there is Room for Improvement in Various Respects. As a Result of the Study, The Following Approaches can be Recommended to Help Prevent Mental Disorders

a. A respectful, supportive management style,

b. A corporate culture explicitly aimed at improving mental

health in its mission statement,

c. Steps to protect employees with an evaluation of the risk

of mental stress factors,

d. Measures to promote a positive work atmosphere,

e. Opportunities for personal development,

f. Sufficient potential to have an influence in order to

identify more strongly with the company,

g. Policies to enable a good work-life balance,

h. Establishing a culture based on trust,

i. Work perceived as being meaningful and varied.

Behavioral prevention strategies provide opportunities to improve health skills, such as learning about personal stress and time management, resilience training, and mindfulness-based interventions [8]. However, few well-designed evaluation studies have been carried out on resilience training and mindfulnessbased interventions in a professional environment [10]. Primary preventive measures are in principle always to be welcomed, but the real challenge for companies and managers is reacting promptly and appropriately to specific cases, i.e. employees who are already showing the first signs of possible mental illness.

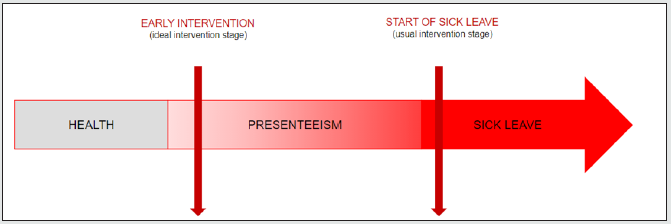

Secondary prevention (early intervention)

A survey of 312 psychiatrists in Germany showed that around 26% of all mental illnesses are primarily caused by stressful circumstances at work – and that figure is growing [11]. This makes early intervention especially important, alongside the primary preventive steps mentioned above. Mental illness develops over a long period of time, which should provide a sufficiently large window of opportunity to intervene early and effectively. However, this requires a certain level of sensitivity on the part of business management to notice the behavioral changes and drop in performance of an affected employee that indicate undue levels of mental stress.

Early Warning Signs Include

a. Chronic irritability, frequent conflicts with colleagues,

b. Withdrawal from the team, resigned behavior,

c. Drops in performance at work, frequent excuses for

incomplete work,

d. Crying without an obvious reason.

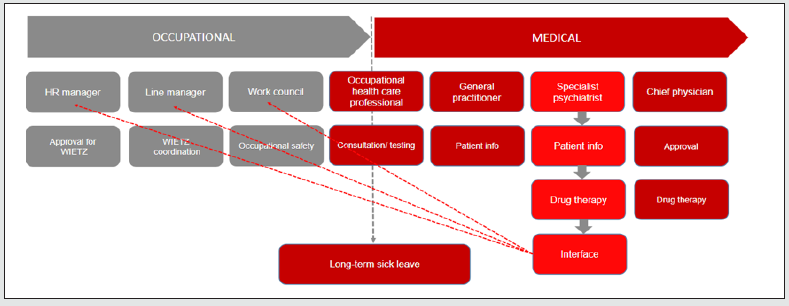

These are just some examples of behavior that may indicate the onset of mental illness. Business managers should not just look away when a case begins to develop. Instead, they should show concern for their employee’s welfare by talking to them in private at an early stage and, if required, telling them about the available treatments. Occupational health care professionals have a major role to play as the interface between the workplace and psychosocial treatment services. Targeted management training workshops providing basic skills for responding to mental illness and practice-based training for handling these sensitive conversations using tried-andtrusted guidelines have been proven to work very well at a number of companies.

It is recommended to refrain from giving well-intentioned but inexpert advice such as “Take a few days off”. Neither should (suspected) diagnoses or recommended treatments be expressed, as this is not the responsibility of business managers. Of prime importance in the company’s interest is that the performance of the employee in question return to normal levels. Good managers should have the appropriate skills to handle sensitive conversations, such as active listening, displaying sympathy, and focusing on the key issues arising from the conversations. By meeting their duty of care, and by informing employees confidentially of the professional treatment available (if appropriate), managers can avoid long periods of presenteeism with reduced performance and long absences on sick leave. It does not need to be explained that this goes hand in hand with an enormous potential to save money, and that a clearly defined policy will benefit both management and the team (Figure 7).

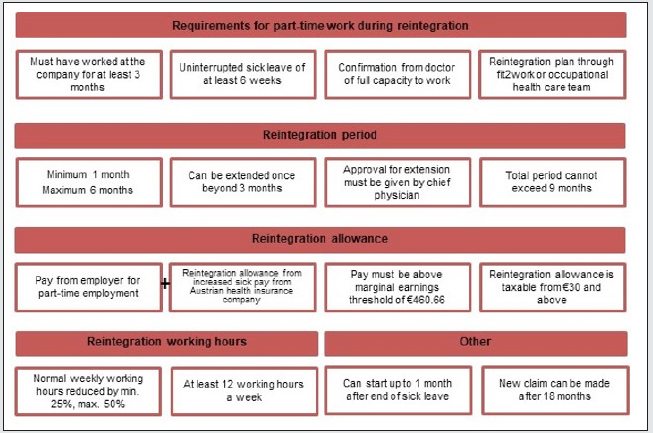

Tertiary Prevention (Rehabilitation)

In addition to the pre-existing rehabilitation services for mental illness, the introduction of a law in Austria regulating part-time work during reintegration (known as WIETZ) [12] on 1 July 2017 represented another major step forward in tertiary prevention. It gives employees the opportunity to ease themselves back into working routines when returning from lengthy sick leave absences. After long-term sick leave (defined as at least six weeks), working hours can be reduced by up to 50% when returning to a professional environment before gradually being increased until the employee can perform at full capacity. WIETZ stipulates that this readjustment period can last between one and six months, though if required it can be extended by a further three months. In addition to receiving proportionate pay from their employer, the employee also receives a reintegration allowance funded by health insurance.

Although WIETZ does not obligate employers in Austria to offer a Company Integration Management (CIM) program, companies in Germany have been legally required to do so since 2004 (CIM in section 167 subsection 2 of Volume 9 of the German Social Insurance Code). German employers must offer a CIM program to all employees who within one year are unable to work for an uninterrupted period of longer than six weeks, or who are repeatedly unable to work. As this legal requirement results in clear structural benefits for the implementation and procedure of a CIM program, 18 companies in Upper Austria, with 24,000 employees in total, have agreed to voluntarily adopt this requirement in line with the German model (CIM Network Austria) [13]. A large study and research report (known as EIBE 2) conducted on behalf of the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs has also made a compelling case for the economic and business benefits of a CIM program, demonstrating a Return on Investment (ROI) of 1:4.81. In other words, each euro invested leads to a future saving of 4.81 euros [14].

CIM is a key tool for preventing employee absence due to sick leave, which is particularly important when there is a shortage of specialists in the workforce, so it pays off for an employer to offer CIM to its employees. And for the employees themselves, CIM (which is always voluntary) can help prevent unemployment or the need to draw an incapacity pension [15] (Figure 8). In this context, mention should also be made of a synthesis of systematic reviews of databases from between 2000 and 2012 to determine the level of evidence for mental health interventions in the workplace. The search resulted in 3363 titles, of which 14 were eventually found to meet the inclusion criteria and were summarized in the synthesis. The synthesis reported on workplace mental health interventions that impacted absenteeism, productivity, and financial outcomes. It concluded that there is positive evidence for the effectiveness of workplace mental health interventions (in particular multicomponent mental health and/or psychosocial interventions and exposure in vivo containing interventions for particular anxiety disorders). The authors also stated, however, that due to the complexity of the issue further research was required in order to provide clear guidance for business managers on the best workplace mental health interventions.

The Role of Psychiatrists in Reintegration

As psychiatrists, we can make our patients aware that WIETZ can help. The occupational health care professional is their first port of call at work, and they can work with the patient to develop a reintegration plan. If the company does not have an occupational health care professional, patients can use the “fit2work” program (Figure 9).

Example of Successful Reintegration

A manager from the IT sector with diagnosed moderate depression and burnout syndrome was on sick leave for three months, during which time he was treated as an outpatient at our hospital with both drug therapies and additive non-drug therapies. Although his concentration levels and resilience in particular remained limited, he was informed at an early stage of the possibility of part-time work as part of his reintegration. After consulting with contact persons at his company, such as the occupational health care professional and his HR manager, the company approved this step and agreed a period of part-time work of five months to aid his reintegration. This meant he could be eased back in by gradually increasing his workload, which proved to be extremely beneficial for his rehabilitation. On the patient’s request, the company was also able to involve the HR manager to discuss various strategies for tailoring his workload to his levels of resilience. Reintegration was viewed as a process which required continuous monitoring and support. To this end, short weekly feedback conversations were arranged with the HR manager over the first few months to review the effectiveness of the agreed steps. The employee is now fully recovered and performing at normal levels.

References

- Evidence to Practice in Mental Health and Work. OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Leoni T Fehlzeitenreport (2019) Absence Report 2019. Sickness and accident-related absenteeism in Austria - The flexible working world: Working hours and health, WIFO.

- (2019) Austrian pension insurance institution. Annual report of the Pension Insurance Fund 2019.

- Leoni T Böheim R (2018) Absenteeism report 2018: Sickness and accident-related absenteeism in Austria - presenteeism and absenteeism.

- (2018) Health at a glance: High costs of mental illness in Europe, OECD.

- Leka S, Nicholson PJ (2019) Mental health in the workplace. Occup Med 69: 5–6.

- Riechert I (2015) Mental disorders in employees: A guide for managers and HR managers - from prevention to reintegration. (2nd edn) Springer, Berlin Heidelberg.

- Berger M, Hecht H, Al-Shajlawi A (2004) Mental illnesses: Clinic and therapy; with systematic consideration of reviews by the Cochrane Collaboration and the Center for Reviews and Dissemination. Additional electronic chapter “Stigma”. (2nd edn); Elsevier Urban & Fischer, Munich.

- Fuchs T, Bielenski H (2006) What is good work? Requirements from the point of view of employed persons; Conception and evaluation of a representative study. (2nd edn); New York.

- Nicholson PJ (2018) Common mental disorders and work. Br Med Bull 126(1): 113.121.

- Mendel R, Hamann J, Kissling W (2010) From taboo to cost factor - why the psyche is suddenly an issue for companies. Business Psychology Current.

- Austrian Federal Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Health and Consumer Protection.

- (2019) Betriebsservice.

- German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs.

- Wagner SL, Koehn C, White MI, Harder HG, Schultz IZ, et al. (2016) Mental health interventions in the workplace and work outcomes: A best-evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Int J Occup Environ Med 7(1): 1-14.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...