Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6628

Case Report(ISSN: 2637-6628)

COVID-19-Induced Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM) Volume 6 - Issue 2

Marley DeVoss1, Chris Yao1, Vibhav Bansal2, Vijayta G Bansal2, Paul J Pecorin1 and Sarah Linder2*

- 1University of Illinois College of Medicine in Rockford, USA

- 2Mercyhealth, USA

Received: February 25, 2022; Published: March 10, 2022

Corresponding author: Sarah Linder, FNP-BC, Mercyhealth, 8201 E Riverside Blvd. Rockford, IL 61111, USA

DOI: 10.32474/OJNBD.2022.06.000233

Abstract

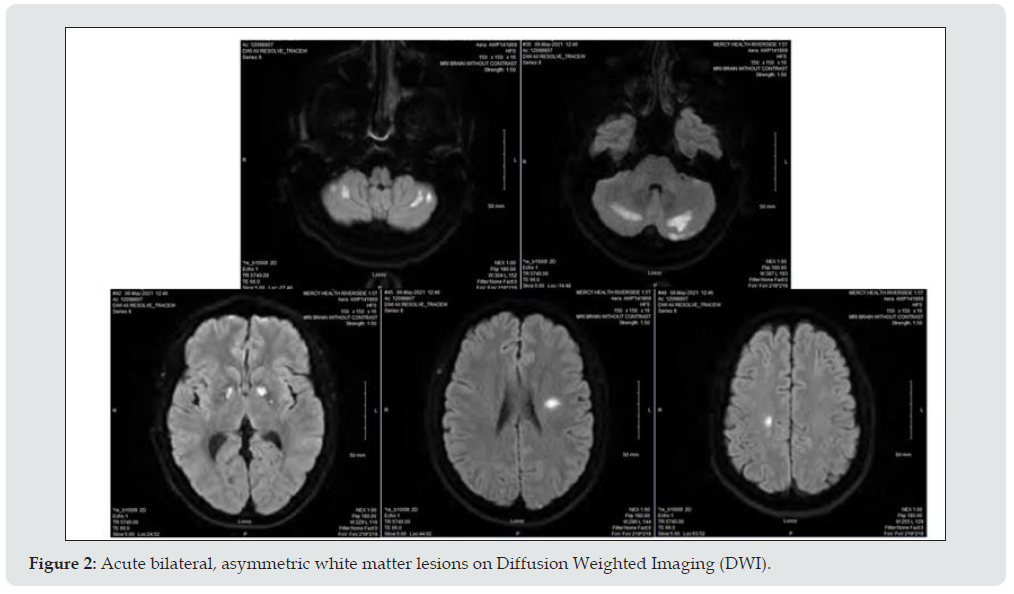

A 39-year-old male was admitted to the intensive care unit with altered mental status, acute encephalopathy, and rhabdomyolysis. The patient was intubated for a total of 5 days for airway protection and acute respiratory distress. MRI imaging revealed bilateral, asymmetric white matter lesions characteristic of a demyelinating disorder. Clinical, imaging, and CSF findings were indicative of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Intravenous high-dose methylprednisolone was administered along with 5 days of plasmapheresis resulting in clinical improvement. The SARS-COV-2 pandemic has manifested many complex neurological presentations, and ADEM should be considered on the differential for COVID-19 patients presenting with acute encephalopathy and multifocal neurologic deficits.

Keywords: COVID; ADEM; Acute Demyelinating Encephalomyelitis

Introduction

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an autoimmune demyelinating disorder that affects the central nervous system. While the pathogenesis of ADEM is not completely understood, ADEM has been associated with vaccinations or preceding viral infections of the upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tracts. More recently, the SARS-COV-2 virus has been shown to produce various neurological complications including ADEM. ADEM presents with rapid onset encephalopathy and multifocal neurologic deficits.

Case Report

The patient was presented to the emergency department after being found unresponsive by emergency medical services who were called to perform a wellness check by a friend. On the initial exam, he was noted to be breathing spontaneously with pinpoint pupils in his bed. During transit, the patient was given 4mg IM Narcan by EMS due to suspected drug overdose with no improvement in his mental status. Upon arrival at the emergency department, the patient remained unresponsive (Glasgow coma score 6) and was intubated and sedated on propofol for airway protection. A urine drug screen was negative. The patient was confirmed from nasopharyngeal swab to have SARS-COV-2 on the third day of admission.

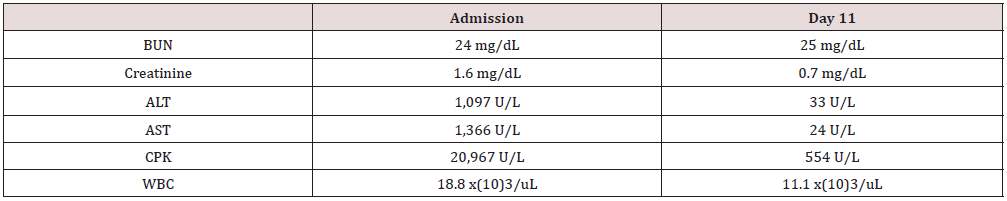

Critical care admission was complicated by left popliteal DVT, acute kidney injury, and extensive aspiration pneumonia seen on chest x-ray (Figure 1) and sputum cultures were positive for methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. The patient was given anticoagulation with Lovenox (enoxaparin) and Eliquis (apixaban) and started on an antibiotic course with vancomycin and ceftriaxone. He was placed with a non-tunneled central venous hemodialysis catheter for acute kidney injury on day 2 of admission. Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI) revealed multiple, bilateral, asymmetric white matter lesions characteristic of a demyelinating disorder. The patient was initiated on high dose steroid regimen with 1000mg IV methylprednisolone daily for 2 days with taper to 6 mg oral dexamethasone for management of suspected ADEM. The patient was also started on plasmapheresis for 5 days. A lumbar puncture was performed with IR guidance and CSF analysis showed mildly elevated glucose and negative for oligoclonal bands. Further CSF workup revealed negative testing for cryptococcus, meningitis, multiple sclerosis, West Nile virus, and Lyme disease PCR. Seizure activity was evaluated due to his elevated CPK levels. EEG showed diffuse slowing consistent with encephalopathy with no epileptiform changes. CPK and elevated ALT/AST were most likely secondary to muscle wasting from lying unresponsive with an unknown last known normal. The patient was weaned off sedation and extubated on day 5 of care, he was alert and able to follow commands at that time. He was sufficient of room air and passed his swallow study and was cleared on honey thick liquids with precautions. His cognitive function continued to improve, and he was able to converse; no focal neurological deficits were observed (Table 1).

Differential Diagnosis

Drug overdose

With the limited history of the patient upon arrival to the emergency department and patient’s initial presentation of somnolence and stupor, drug overdose and metabolic causes were at the top of the differential list. The family later gave a history of unknown drug use. This became less likely when the urine tox screen came back negative. In addition, the patient did not significantly improve with Narcan administration.

Shock liver 2/2 Anoxic Injury 2/2 Respiratory Distress

With this patient’s high elevation of liver enzymes in addition to the elevated stress response indicators (glucose, WBC), shock liver was to be considered. This was less likely due to the patient’s oxygen and blood gas conditions upon admission. His arterial pH was 7/36 and oxygen saturation at 98%.

Acute Stroke

The MRI showed multiple hyperdense lesions that required the consideration of multiple acute strokes. Originally, it was thought that these were secondary to anoxic brain injury from lack of perfusion while the patient was in distress and unconscious. However, his oxygen status was good upon arrival and the finding and the MRI findings in watershed infarct are in the cortical regions that share blood supply from the anterior cerebral, middle cerebral, and posterior cerebral arteries. His lesion in the subcortical, deep brain, and cerebellar regions (Figure 2) make this a less likely cause.

Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

This patient’s MRI findings of acute, bilateral, asymmetric white matter lesions with his presentation of encephalopathy and exclusion of other demyelinating disorders from CSF, and positive COVID result made the diagnosis of COVID-associated ADEM the most likely etiology for his admission. The patient had a physiological stress response leading to his elevation of leukocytes and glucose in his blood. His high elevation of CPK and AST/ALT can be explained by muscle wasting from an unknown amount of days of unconsciousness due to altered mental status and encephalopathy. The patient’s LP workup was negative for other possible etiologies.

Discussion

ADEM

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is commonly precipitated by a viral infection triggering an autoimmune demyelinating response. It presents with an acute onset of focal neurological deficit with encephalopathy [1-4]. The neurological findings depend on the corresponding location of each lesion. All lesions have the potential for seizure activity and development into status epilepticus. This disease has the highest incidence in children with complete to partial recovery to baseline with appropriate therapy [5]. Diagnosis of ADEM relies on a combination of characteristic MRI abnormalities, clinical presentation, as well as the exclusion of other immune-related diseases and/or infectious etiologies. In patients with suspected ADEM, neuroimaging with MRI is the diagnostic tool of choice. An MRI of the head will typically show multifocal, asymmetric white matter lesions throughout the CNS. Obtaining a lumbar puncture for CSF analysis is an important step in determining the etiology of acute encephalopathy. To date, no CSF findings specific to ADEM from COVID have been described. Previous post-COVID ADEM cases have noted widely variable CSF findings from oligoclonal IgG bands to abnormal glucose, protein, or cell counts [3-7]. Therefore, it is necessary to correlate these findings with the patient’s clinical picture in order to determine the underlying etiology. Once a diagnosis of ADEM has been established, current standards of care involve initiation of high-dose glucocorticoid regimen, plasmapheresis, and/or infusions of IVIG6. Close follow up is recommended with serial MRI, EEG, and modified Rankin Scale to assess neurological disability and improvement [1].

References

- Höllinger P, Sturzenegger M, Mathis J, Gerhard Schroth, Christian W Hess (2002) Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in adults: A reappraisal of clinical, CSF, EEG, and MRI findings. J Neurol 249: 320-329.

- Langley L, Zeicu C, Whitton L, Pauls M (2020) Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) associated with COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 13(12): e239597.

- McCuddy M, Kelkar P, Zhao Y, Wicklund D (2020) Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM) in COVID-19 infection: A case series. Neurol India 68(5): 1192-1195.

- Parsons T, Banks S, Bae C, Gelber J, Alahmadi H, Tichauer M (2020) COVID-19-associated acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). J Neurol 267(10): 2799-2802.

- Pohl D, Alper G, Van Haren K, Andrew J Kornberg, Claudia F Lucchinetti, et al. (2016) Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: Updates on an inflammatory CNS syndrome. Neurology 87(9_Supplement_2): 38-45.

- Schwarz S, Mohr A, Knauth M, B Wildemann, B Storch-Hagenlocher (2001) Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study of 40 adult patients. Neurology 56(10): 1313-1318.

- Sonneville R, Demeret S, Klein I, Lila Bouadma, Bruno Mourvillier, et al. (2008) Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in the intensive care unit: Clinical features and outcome of 20 adults. Intensive Care Med 34: 528-532.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...