Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6628

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6628)

A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Acediprol (Valproate Sodium) For Global Severity in Child Autism Spectrum Disorders Volume 2 - Issue 1

NA Aliyev1* and ZN Aliyev2

- 1Department of psychiatry and addiction, Azerbaijan State Advanced Training Institute, Azerbaijan

- 2Department of psychiatry, Azerbaijan Medical University, Azerbaijan

Received: September 22, 2018; Published: September 28, 2018

Corresponding author: Nadir A Aliyev, Department of psychiatry and addiction, Azerbaijan State Advanced Training Institute, Baku, Azerbaijan

DOI: 10.32474/OJNBD.2018.02.000127

Abstract

Objectives: The effects of Valproate sodium and placebo on global severity were compared in Child Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD).

Materials and Methods: Childs with ASDs were enrolled in a 12-week double-blind placebo-controlled Valproate sodium trial. Fifty were randomly assigned to Valproate sodium (n=50) or placebo (n=50). The initial dose of Valproate sodium for children is 15mg/kg, then increases by 5-10mg/kg every week to 20-50mg/kg. Children are given 5% syrup (Sirupus Valproate sodium 5%), 1 ml 50mg. Repetitive behaviors were measured with the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) improvement scale.

Results: There was a significant treatment-by-time interaction indicating a significantly greater reduction in repetitive behaviors across time for Valproate sodium than for placebo. With overall response defined as a CGI global improvement score of 2 or less, there were significantly more responders at week 12 in the Valproate sodium group than in the placebo group. The risk ratio was 1.5 for CGI global improvement (responders: Valproate sodium, 80%; placebo, 12%). Side effects were not observed.

Conclusion: Valproate sodium treatment, compared to placebo, resulted in significantly greater improvement in global severity< behaviors, according to CGI rating scale. Valproate sodium appeared to be well tolerated movement score of 2 or less, there were significantly more responders at week 12 in the Valproate sodium group than in the placebo group. The risk ratio was 1.5 for CGI global improvement (responders: Acedipro, 80%; placebo, 12%). Side effects were not observed.

Introduction

Currently, disorders of the autism spectrum are the most urgent problem of modern psychiatry. It is no accident that the Sixty-Seventh World Health Assembly adopted a resolution called “WHA67.8 Integrated and coordinated efforts to combat autism spectrum disorders.” In particular, the document says: “Understanding that autism spectrum disorders are developmental disorders and conditions that emerge in early childhood and, in most cases, persist throughout the lifespan and are marked by the presence of impaired development in social interaction and communication and a restricted repertoire of activity and interest, with or without accompanying intellectual and language disabilities; and that manifestations of the disorder vary greatly in terms of combinations and levels of severity of symptoms” [1]. In one hand, last several decades based on epidemiological studies conducted over the past 50 years, the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) appears to be increasing globally. There are many possible explanations for this apparent increase, including improved awareness, expansion of diagnostic criteria, better diagnostic tools and improved reporting. It is estimated that worldwide 1 in 160 children has an ASD. Other authors indicated that autism spectrum disorder currently estimated to affect between 1 and 1.5% of children and adults worldwide [2,3]. In other hand, the cost of supporting an individual with an ASD and intellectual disability during his or her lifespan was $2.4 million in the United States and £1.5 million (US $2.2 million) in the United Kingdom. The cost of supporting an individual with an ASD without intellectual disability was $1.4 million in the United States and £0.92 million (US $1.4 million) in the United Kingdom [4].

It is known that autism spectrum disorder, previously known as the pervasive developmental disorders, is a phenotypically heterogeneous group of neurodevelopmental syndromes, with polygenic heritability, characterized by a wide range of impairments in social communication and restricted and repetitive behaviors. Prior to the development of the Fifth Edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), autism spectrum disorder was conceptualized as five discrete disorders, including: autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, Rett syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified [5]. Autistic disorder was characterized by three core symptom areas: impairments in three domains: social communication, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and aberrant language development and usage. Medications are mainly used to treat the associated symptoms of an autism spectrum disorder, as the effectiveness of use in treating the main symptoms of autism is not established. In addition to psychosocial therapy of autism, there are data in the literature on the use of typical (haloperidol) and atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole, olanzapine, lurasidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone, paliperidone), antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and others), mood stabilizers, stimulants (stimulants / atomoxetine / alpha-2 agonists) and other agents for the treatment of autism spectrum disorders [6]. The aim of this study was examining the effects of Valproate sodium and placebo on global severity were compared in child autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Materials and Methods

In accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association “Recommendations for doctors engaged in biomedical research involving people”, adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly (Finland, 1964, revised in Japan in 1975, Italy - 1983, Hong Kong - 1989, the South African Republic - 1996, Edinburgh - 2000); The Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan, the Law “On Psychiatric Assistance” (adopted on 12.06.2001, with amendments and additions -11.11.2011, Decisions of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Azerbaijan No. 83, dated April 30, 2010 “On Approval of the Rules for Conducting Scientific, Preclinical and Clinical studies of medicines” are established. The conditions of the conducted researches corresponded to the generally accepted norms of morality, the requirements of ethical and legal norms, as well as the rights, interests and personal dignity of the participants of the studies were observed.

a) Conducted research is adequate to the topic of research work.

b) There is no risk for the subject of research.

c) Participants in the study were informed about the goals, methods, expected benefits of the study and associated with risk and inconvenience in the study.

d) The subject’s informed consent about participation in the research was received.

The decision of the Ethical Committee at the Azerbaijan Psychiatric Association on the article of NA. Aliev, Z.N. Aliev “A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Valproate sodium (Valproic Acid) for Global Severity in Child Autism Spectrum Disorders” submitted for publication in psychiatric journals: in connection with compliance with its legislative requirements and regulatory documents is to approve the article by N.A. Aliyev, Z.N. Aliev “A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Valproate sodium for Global Severity in Child Autism Spectrum Disorders”. We examined 100 patients with (FI0.239). Patients were observed at the Mental Health Center of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Azerbaijan (from January 2012 to December 2017 years). Fifty subjects were children aged 5–17 years, outpatients, who met DSM-V diagnostic criteria for autistic disorder. Subjects had to be at least moderately ill (CGI-Severity score of at least - 4) to justify exposure to this medication.

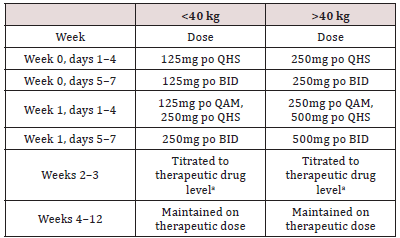

We excluded sexually active subjects with active or unstable epilepsy, other genetic syndromes or congenital infections associated with autistic-like syndromes, prematurity; subjects who have been treated within the previous 30 days by any medication known to have a clearly defined potential for toxicity or with any psychotropic drugs; Subjects with clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory tests or physical examination; subjects with a history of hypersensitivity or serious side effects associated with the use of Valproate sodium (or other ineffective previous therapeutic tests of Valproate sodium ((serum levels in the range of 50-100μg /mL for 6 weeks); and subjects who, during the previous 3 months, started new non-pharmacological procedures, such as diet, vitamins and psychosocial therapy. A detailed clinical interview with parents by a clinical expert, accompanied by physical examination and blood analysis, was used to ensure that subjects did not meet any exclusion criteria. The method of randomization was given by lottery. This was a 12-week randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Participants were randomized to Valproate sodium vs placebo and the dose was titrated up according to body weight (Table 1). Therapeutic blood level (a minimum valproate blood level of 50μg/ml, as is the established minimum for epilepsy), and ultimately treatment response. All clinicians involved in efficacy or safety assessments were blinded to the randomization condition. Efficacy measures were administered every 2 weeks by an independent evaluator, who was an experienced clinical psychologist blinded to side effects. Side effects were monitored by study physicians, who are experienced in treating children with ASD and using Valproate sodium formulations. The dose was titrated on the basis of feedback from a nonblinded physician who independently monitored blood. This clinician had no contact with the participants. All valproate levels and safety blood results were forwarded to him by the laboratory. He then instructed the study physicians to decrease, maintain, or increase the dose. Feedback on subjects randomized to placebo was based on a blocked schedule, so that all study clinicians remained blinded to the condition of randomization.

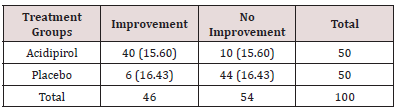

Table 1: Titration Schedule (Valproate sodium vs Placebo for the Treatment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders). aBased on clinical response in conjunction with minimum valproate sodium level (50μg/ml).

The dose for children is selected individually depending on the age, the severity of the disease, the therapeutic effect. Usually the daily dose for children is 20 - 50mg per 1kg of body weight, the highest daily 60mg/kg. Begin treatment with 15mg/kg, then increase the dose every 5 to 10mg/kg until the desired effect is achieved. The daily dose is divided into 2 - 3 doses. It is convenient for children to prescribe the drug in the form of a liquid dosage form - acetiprol 5% syrup (Sirupus Acediproli 5%) containing 50mg of the drug in 1ml. The necessary amount of syrup is measured with a dosage spoon with divisions of 2, 5 and 5ml. Independent samples t-tests were used to determine whether there were baseline differences between treatment groups on the following potential covariates baseline severity. Also, was used χ2analysis. Outcome measure: CGI-I (χ2analysis). Consistent with intent-to treat principles, for those subjects missing the week-12 ratings, we imputed their value on the CGI at week 12 using mixed regression models based on the available values from all subjects and all seven time points. The predicted scores were then used to classify the subjects as responders or non-responders at week 12 on the basis of the following: CGI< 2 (responders) or CGI>2 (nonresponders). χ2 test was used to compare the response between groups.

Results

We evaluated efficacy using the Clinical Global Impression- Improvement Scale (CGI-I). The CGI-I is a 7-point improvement scale. Ratings of 1 or 2 (responders) indicate a substantial reduction in symptoms, so that a treating clinician would be unlikely to readily change the treatment regimen. A rating of 3 (minimally improved) on the CGI is defined as a slight symptomatic improvement that is not deemed clinically significant; patients with such an improvement were not considered responders. A physical examination was conducted at baseline and end visits. Blood monitoring of hematopoietic, liver, and renal function was carried out at baseline, weeks 2 and 4, and at end visit. Weight, height, and BMI were recorded at baseline and at end visit and vital signs were taken at baseline, weeks 2 and 4, and at end visit. Adverse event monitoring took place every week for the first 4 weeks and every 2 weeks thereafter. Questioning was focused on known side effects of Valproate sodium, followed by openended questioning. Valproate sodium was well tolerated within this group. Side effects were not observed. Expected numbers indication in the brackets, χ2analysis = 22.68, df = 1. P < 0.001. There was a significant treatment-by-time interaction indicating a significantly greater reduction of ASD generally symptoms across time for Valproate sodium than for placebo. With overall response defined as a CGI global improvement score of 2 or less, there were significantly more responders at week 12 in the Valproate sodium group than in the placebo group. The risk ratio was 1.5 for CGI global improvement (responders: Valproate sodium, 80%; placebo, 12%). Side effects were not observed (Table 2).

Discussion

This study suggests that Valproate sodium may be effective in the treatment of ASD. There are several reasons why this may be the case. First, the GABA-enhancing mechanism of valproate may be relevant to both the pathophysiology of aggression and that of ASD [7,8]. Second, the documented ability of valproate to inhibit kindling has been proposed as an additional mechanism that may explain its effectiveness in treating mood lability, and as such, may be particularly important in the treatment of irritability [9]. Third, the treatment of underlying epileptiform abnormalities may contribute to behavioral response. This theory, although controversial, is supported by our very preliminary data that showed that children randomized to Valproate sodium (with epileptiform EEGs were classified as responders. This hypothesis is further supported by a report by some authors [10]. We would also like to make note of our findings suggesting that therapeutic blood levels of Valproate sodium are associated with better response. The safety profile of Valproate sodium in this study was very good. One should not assume though that the safety profile of a medication in a short-term study would be reflective of a long-term safety with this medication.

This study suggests that Valproate sodium may be effective in the treatment of ASD. There are several reasons why this may be the case. First, the GABA-enhancing mechanism of valproate may be relevant to both the pathophysiology of aggression and that of ASD [7,8]. Second, the documented ability of valproate to inhibit kindling has been proposed as an additional mechanism that may explain its effectiveness in treating mood lability, and as such, may be particularly important in the treatment of irritability [9]. Third, the treatment of underlying epileptiform abnormalities may contribute to behavioral response. This theory, although controversial, is supported by our very preliminary data that showed that children randomized to Valproate sodium (with epileptiform EEGs were classified as responders. This hypothesis is further supported by a report by some authors [10]. We would also like to make note of our findings suggesting that therapeutic blood levels of Valproate sodium are associated with better response. The safety profile of Valproate sodium in this study was very good. One should not assume though that the safety profile of a medication in a short-term study would be reflective of a long-term safety with this medication.

These activities appear to be mediated, at least in part, by its effects on GABA- mediated neurotransmission. Valproate sodium increases CNS concentrations of GABA, possibly by increasing its synthesis and/or inhibiting its catabolism. Valproate sodium has also been reported to decrease neurotransmission by the excitatory amino acids (-hydroxybutryc, aspatic and glutamic acids), to inhibit cell firing induced by Af-methyl-D-aspartate, and to exert a direct neuronal membrane depressant effectf via modulation of sodium and potassium conductance. Valproate sodium is generally well tolerated, does not induce hepatic drug metabolism and has a low propensity for interactions with psychotropic agents. Limitations of our study include the relatively small sample size, which did not allow for a complete analysis of EEG and valproate blood level data. In addition, the absence of an EEG record at the end of the study makes it impossible for investigators to determine whether an improvement in EEG patterns correlated with treatment response. The choice of the ABC-Irritability subscale, although a validated measure in ASD, precludes us from making recommendations regarding specific types of aggression that may be responsive to Valproate sodium. The fact that only seven children had previous exposure to an atypical antipsychotic also did not allow us to explore whether those with previous risperidone treatment were less responsive to valproate vs those without previous risperidone, and this remains a question for a future trial.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a Valproate sodium in the acute Treatment of outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder without of psychiatric comorbidity. Our data suggest that Valproate sodium is efficacious in the management of acute anxiety disorders, as the participants had a clinically and statistically significant improvement in anxiety symptoms over 6 weeks of treatment. Our data are also consistent with these findings [20,21]. The rational use of pharmacological treatment in generalized anxiety disorders is still a matter of debate due to the uncertainties concerning the nature, diagnostic criteria and target-symptoms of this frequent and potentially invalidating disorder. Mechanisms underlying the pathological characteristics of the ASD have yet to be fully elucidated. One of the most widely accepted mediators known to play a central role in the pathophysiology of anxiety disorders is the g-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system. Evidence supporting the role of a dysfunctional GABA system has resulted from clinical experience with the benzodiazepines, as well as subsequent determination of mechanism of action, genetic engineering, and neuromaging studies of the GABA receptor. Valproate sodium is a sample branched chain fatty acid that was originally developed for the treatment of epilepsy. In addition to its anticonvulsant activity, Valproate sodium has demonstrated anxiolytic, mood-stabilizing, antimigraine and antinociceptive effects and has been evaluated in the management of various other disorders, particularly psychiatric conditions. These activities appear to be mediated, at least in part, by its effects on GABA - mediated neurotransmission. Valproate sodium increases CNS concentrations of GABA, possibly by increasing its synthesis and/or inhibiting its catabolism. Valproate sodium has also been reported to decrease neurotransmission by the excitatory amino acids (-hydroxybutryc, aspatic and glutamic acids), to inhibit cell firing induced by Af-methyl-D-aspartate, and to exert a direct neuronal membrane depressant effectf via modulation of sodium and potassium conductance. Valproate sodium is generally well tolerated, does not induce hepatic drug metabolism and has a low propensity for interactions with psychotropic agents. However, as has been observed with several other antiepileptic drugs, it is teratogenic and can cause elevated hepatic enzyme levels and rare, fatal hepatotoxicity [22].

Two limitations should be noted. First, our small study group and we recommend that these results be replicated in a larger group so that effect sizes can be more precisely estimated. Second, it is necessary study of possibility generalizability these data to girls. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study suggests that, depakine-chrono are efficacious and well tolerated in the treatment ASD. In any event, pending a further understanding of valproate’s mechanisms of action, the present data suggest that this drug is a useful new agent for the treatment of ASD.

Author Disclosure Information

The authors declare that the article is submitted on behalf of all authors. None of the material in the article has been published previously in any form and none of the material is currently under consideration for publication elsewhere other than noted in the cover letter to the editor. Authors declare no financial and personal relationship with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence this work. All authors contributed to and have approved the final article. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No sponsor provided funding for this study. Mental Health Center of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Azerbaijan provided the outpatient unit, the material for clinical and neuro-psychological assessments, and electronic resources.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank staff of the Mental Health Center of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

References

- (2014) WHO Resolution on autism spectrum disorders (WHA67.8) In May, the Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly adopted a resolution entitled “Comprehensive and coordinated efforts for the management of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) Autism spectrum disorders. Fact sheet Updated April 2017.

- Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Chandler S, Loucas T, et al. (2006) Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet 368(9531): 210-215.

- (2012) Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, USA, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ 61(3): 1-19.

- Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS (2014) Costs of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr 168(8): 721-728.

- (2013) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (5th Edn) American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, Virginia, USA.

- Sheena LeClerc, Deidra Easley (2015) Pharmacological Therapies for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. Pharmacy and Therapeutics PT 40(6): 389-397.

- Bjork JM, Moeller FG, Kramer GL, Kram M, Suris A, et al. (2001) Plasma GABA levels correlate with aggressiveness in relatives of patients with unipolar depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res 101(2): 131-136

- Casanova MF, Buxhoeveden D, Gomez J (2003) Disruption in the inhibitory architecture of the cell minicolumn: implications for ASD. Neuroscientist 9(6): 496-507.

- Soderpalm B (2002) Antivonvulsants: aspects of their mechanism of action. Eur J Pain 6: 3-9.

- Stoll AL, Banov M, Kolbrener M, Mayer PV, Tohen M, et al. (1994) Neurologic factors predict a favorable valproate response in bipolar and schizoaffective disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 14(5): 311-313.

- Valproic acid (Depakene, Abbott). In: PDR Physician’s Desk Reference (43rd edn) 1989. Oradell, NJ: Medical Economics Company, 1989: 511-3; (51st edn.) 1997: 416-418.

- Valproic acid (Depakene, Abbott). In: Krough CME, editor. CPS Compendium of pharmaceuticals and specialties (24th edn). Ottawa: Canadian Pharmaceutical Association, 1989: 292-293: (32nd edn.). 1997: 427-429.

- Divalproex (1989) Depakote, Abbott. In: PDR Physician’s Desk Reference (43rd edn.). Oradell, NJ: Medical Economics Company 513-4: 418-22.

- Divalproex (Epival, Abbott). In: Krough CME, editor. CPS Compendium of pharmaceuticals and specialties. 24th ed. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmaceutical Association, 1989: 372-3: 32nd ed. 1997: 538-40.

- Valproic acid capsules (Reid-Rowell-US) package insert, Rev 1/89; Rec 4/89.

- Valproate sodium injection package insert (Depacon, Abbott-US), Rev 1/97, Rec 3/24/97.9-13, 42.

- Rimmer RM, Richens A (1985) An update on sodium valproate. Pharmacotherapy 5(3): 171-184.

- Macdonald RL (1989) Antiepileptic drug actions. Epilepsia 30(Suppl 1): SI9-S28.

- Panelist comment 2: 90.

- Eric Hollander, William Chaplin, Latha Soorya, Stacey Wasserman, Sherry Novotny, et al. (2010) Divalproex Sodium vs Placebo for the Treatment of Irritability in Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 990-998.

- Melissa De Filippis, Karen Dineen Wagner (2016) Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull 46(2): 18-41.

- Balfour JA, Bryson HM (1994) Valproic Acid. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in indication other than epilepsy. CNS Drug 2: 144-173.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...