Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-6062

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-6062)

Reentry Program Combines Therapeutic Community, Rehabilitation, Work Release and Parole: Long Term Outcomes Volume 1 - Issue 4

Sharon Swan1 and Jerry Jennings2*

- 1Executive Director of Bermuda Transitional Living Center, Liberty Healthcare Corporation, Pennsylvania

- 2Vice president of Clinical Services, Liberty Healthcare Corporation, Pennsylvania

Received: June 09, 2018; Published: June 19, 2018

*Corresponding author: Jerry Jennings, Vice president of Clinical Services, Liberty Healthcare corporation, 401 E. City Ave, Suite 820, Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, 19004

DOI: 10.32474/PRJFGS.2018.01.000118

Abstract

This innovative re-entry program combined an in-prison therapeutic community, work release, and employment and housing reentry with parole/aftercare support to rehabilitate and reintegrate offenders with high levels of criminality and substance abuse. Statistically significant outcomes from a ten year period for 198 offenders showed that only 23% of those who completed the full treatment program and were released on parole were reincarcerated compared to 44% of offenders with partial treatment without parole and 69% for those “rejected from treatment” for program violations. The “partial treatment” group consisted of inmates who were released on the earliest date marking completion of sentence and before finishing the treatment program. Those “rejected from treatment” were reincarcerated at twice the rate of those with full or partial treatment (69% vs. 34%). Reduced reincarceration was significantly correlated with longer lengths of treatment. Analysis of substance abuse types showed that cocaine abusers (and heroin abusers to a lesser extent) had the poorest rates of program completion and the highest and fastest rates of reincarceration following discharge.

Introduction

Research indicates that fewer than half of parolees successfully complete their period of parole supervision without violating a condition of release or committing a new offense [1]. Moreover, two-thirds of all prisoners are rearrested within three years of release [2] and more than half are reincarcerated within three years [3]. Given such high failure rates, criminal justice authorities have turned to prisoner reentry programs as a possible solution. In what has been termed “the reentry crisis,” Listwan, Cullen and Latessa [4] point to the “irresponsibility” of parole officer caseloads that are too high for effective management: “It jeopardizes both the successful reintegration of offenders and the protection of public safety.” At the national level, the Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative and the Federal Second Chance Act also reflect the hope that reentry programs may help more offenders to achieve a successful transition to responsible, law-abiding life.

Similarly, the country of Bermuda has tried to reduce its high rates of reincarceration by using reentry and managing offenders in a more restorative and rehabilitative manner in the community. In 1999, Bermuda’s prisoner population was the fifth highest in the world by population. As part of a broad initiative called “Alternatives to Incarceration,” the Bermuda Department of Corrections launched its Transitional Living Center in 2001 to promote successful, substance-free reentry into the community [5]. Correctional reentry programs address a common array of issues, including development of job skills, employment support, housing assistance, life skills training, and mental health and substance abuse treatment. Optimally, reentry programs have three distinguishable “phases:”

a. A prison-based program that prepares offenders for reentry;

b. A community-based transitional program that assists offenders just prior to and immediately following release; and

c. Extended community-based aftercare support [4,6].

A variety of reentry treatment models have been applied with encouraging results. For young adult offenders without a primary substance abuse focus, a New York-based prisoner reentry program claims a three-year recidivism rate of 10% [7]. For substance abusing inmates, the best results have been achieved when inprison substance abuse treatment is followed by post-release treatment [8]. In particular, the most successful research-based programs have combined intensive in-prison treatment using the therapeutic community (TC) model with transitional and aftercare support. A “TC” is typically defined as a residential community within a prison that features substance abuse counseling and guidance and employs staffs who are role models of successful recovery. At two-year post-release, the Amity Prison TC program in California reduced the rate of reincarceration by 35% compared to controls [9]. A subsequent analysis of the Amity TC and its Vista aftercare program found that participants averaged 51 fewer days incarcerated (36% less) than the control group who received no treatment in prison [10].

Similarly, Knight, Simpson, and Hiller [11] found that only 25% of those who completed in-prison TC program and community aftercare in Texas were reincarcerated within three years of release, compared to 64% of the aftercare drop-outs and 42% of untreated prisoners. The CREST Outreach Center in Delaware delivered a six-month TC work release and aftercare program. At 18 months, this TC work release program reduced reincarceration by an average of 30 fewer days (29% less) than a standard work release program and the aftercare component reduced reincarceration by an average of 49 fewer days (43% less) than work release-only. Although the results were limited by potential selection bias, the triple combination of TC, work release and aftercare appeared encouraging. Subsequent evaluation of the Delaware program reaffirmed that the each of its three treatment components-inprison, transition and aftercare-had beneficial effects, but the transitional residential program had a significantly larger and more long-lasting impact [12]. A parallel study of female offenders in the same Delaware program showed that 40% of the participants were rearrested and/or convicted compared to 60% of the no-treatment controls and that 51% reported drug use and 66% were gainfully employed compared to 77% and 49% of the controls [13].

The same research team later evaluated five year outcomes for 1,122 participants in the Delaware program [14] and found that treatment during work release halved relapse, while treatment before or during prison did not have an impact. They found that 52% of those who received TC work release and aftercare were rearrested compared to 58% receiving work release TC only and 77% of those receiving standard work release. At 55%, the treatment group also had a 10% higher rate of employment than those with no treatment. When other researchers combined a sample of 1,461 inmates from the California, Texas and Delaware reentry programs, they found that about 25% of those receiving intensive drug treatment and aftercare were reincarcerated compared to 75% for those receiving no treatment or in-prison treatment alone [15]. In summary, the best three-year recidivism rates for correctional TC/ work release/ aftercare programs appear to average about 25%. By comparison, the Bermuda Transitional Living Center (TLC) reduced recidivism to just 13% over an 8-year period. This outcome study seeks to elucidate the unique reentry and offender factors that can account for these superior outcomes.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 198 offenders admitted to a freestanding 12-bed residential unit located within the secure perimeter of a maximum security prison between May 2001 and December 2010. There were a total of 175 outcomes because 13 offenders were admitted to the program at least twice. Despite multiple admissions, only one “final” outcome after discharge to the community was counted for each participant in the analysis. Offenders were tracked and outcomes were determined for all participants through July 1, 2009.

Measures

Drug and alcohol abuse history and issues were assessed using the Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory-3 (SASSI-3). Incarcerations and reincarcerations were determined from the Bermuda Department of Correction database.

Procedure

The study collected data pertaining to a range of offender characteristics (e.g., type of crime, primary substance abuse type, number of prior incarcerations, criminal severity and juvenile offense history) and outcomes (e.g., length of treatment, length of time in community before or without reincarceration, number of reincarcerations). Data was extracted from the DOC records and database. Since Bermuda is a small island country of about 65,000 people, the TLC program had the rare opportunity to track longterm outcomes for 100% of its participants over the course of ten years.

Program Description

a. Staff: The interdisciplinary treatment team consisted of one psychiatric nurse, one job developer, and two counselor/ case managers for a maximum capacity of 12 residents. The TLC also used paraprofessional treatment aides, who were crossed-trained to provide 24/7 security functions within the residential unit and assisted residents with life skills training activities, such as meal planning and preparation, housekeeping, and recreational activities. Perimeter security was performed by correctional officers of the main prison.

b. Three Phases of Treatment: There were three phases of treatment, but no specific time frames for completion of each phase. Residents were expected to demonstrate efforts toward rehabilitative change. Each inmate had to have a negative drug test result to be admitted.

c. Phase I-Therapeutic Community and Rehabilitation: Phase I began with an individualized needs assessment and review of all available records, including medical, mental health, substance abuse and criminal/institutional history. The treatment team then completed an assessment of mental health issues, substance abuse history and issues, family and social support network, school and employment history, medical/nursing issues, childhood abuse history, outstanding debts, and other relevant concerns. The treatment team developed an individualized case plan in conjunction with the offender that addressed his foremost treatment needs. The TLC offered an array of services including substance abuse education and counseling, anger management, cognitive interventions to correct criminal thinking, victim awareness, money management, meal planning and preparation, life skills training, wellness, leisure skill development, job preparation, job placement, housing assistance, debt reduction guidance, and linkages to community-based services and supports.

As a therapeutic community, the residents were expected to complete daily chores, participate in meal preparation, and attend community meetings and rehabilitative groups and activities. Residents were expected to exercise as much self-governance as possible to understand how their behavior affects others and to prepare for discharge to the community. When someone failed to complete his assigned chores, the residents as a group decided an appropriate response or consequence. Staff oversaw these functions and intervened only if necessary. Residents were subject to random drug testing and testing for cause throughout the course of their treatment stay. During Phase I, the job developer worked closely with each resident to complete an assessment of work history and vocational skills and interests. In addition to developing partnerships with various community employers, the job developer helped each inmate to create a resume, find a suitable job, prepare for the job interview, and understand the responsibilities of employment. If the offender demonstrated consistent adherence to program expectations, he is given the privilege of employment in the community and entered Phase II.

d. Phase II-Work Release/Employment: During Phase II, the offenders would leave the residential facility each morning to work at their designated jobs in the community and then return at the end of the workday. Each offender was expected to continue to meet his daily residential obligations and attend recommended rehabilitative activities in the TC and to identify a 12-Step Sponsor to support his recovery in the community. Individual job performance was carefully monitored, especially during the initial period of employment, and interventions were made if unsatisfactory. When each offender began earning wages, TLC staff would assist him in setting up a bank account and budget to address his financial obligations, which often included debt reduction, child support, fines or other debts. Payment for bed and board at the TLC was also expected from each inmate.

e. Phase III-Consolidation and Reentry: Phase III was focused on strengthening and consolidating the knowledge and skills learned in the rehabilitative program in order to make a full transition to independent living in the community. The residents were expected to maintain their gains in terms of continued full-time employment, attendance at rehabilitative activities, completion of daily chores, and adherence to 12-Step Fellowship and financial responsibilities. In preparing for release, the TLC staff assisted the residents in finding appropriate, affordable and stable housing. TLC staff determined when an individual was ready to move from one phase to the next by considering progress in treatment, employment performance, staff observations of behavior and social cooperation in the TC, conformance to program rules, and input from other peers in the TC. Staff also monitored the offenders’ behavior in the community by using collateral information from employers, family members, 12-Step sponsors, mental health providers, and other approved persons to cross-validate conduct and compliance.

f. Extended Aftercare Support: Extended aftercare support was available to all TLC participants upon discharge whether they completed the treatment/reentry program or not and whether they were released under parole or not. All participants were encouraged to keep in touch with the TLC program. The TLC staff continued to provide guidance and support to former residents via telephone consultations and by facilitating appointments with appropriate community service providers. In addition, the TLC program offered motivational holiday parties and social events in which Bermuda Ministry and Department of Corrections officials, community employers, and current TLC residents and staff acknowledged the accomplishments of successful TLC alumni.

Data Analysis

Three Comparison Groups-Three Types of Discharge from TLC: Inmates were discharged from the TLC in three ways: The optimal discharge occurred when the treatment team recommended parole for a resident who had achieved his treatment goals and demonstrated responsibility in all aspects of the reentry program (e.g., treatment activities, employment, residential behavior, etc.). If the resident was not ready for release on his parole eligibility date, the TLC team requested an extension of two to six months based on progress to date. All offenders in this discharge category (a total of 41) were then subject to supervision by parole in the community.

The second type of discharge from TLC was called “Earliest Release Date” (ERD). An offender in this category was automatically discharged on the predetermined date when his sentence had ended and he was no longer under the jurisdiction of the Department of Corrections. This was a less desirable form of program discharge because release occurred independent of the individual’s actual progress in treatment. Thus, ERD was regarded as a “partial” treatment condition because the offender was released without recommendation from the treatment team and without having fully completed his treatment goals. Moreover, following release, the ERD individuals were not subject to any on-going parole supervision in the community.

The third type of discharge was considered a “rejection from treatment.” This occurred when an offender was sent back to the main prison because of serious or repeated rule violations in the residential facility. The most frequent reasons for negative discharge were getting caught outside of the approved zones for employment; possession of drugs, alcohol, weapons, cell phones, or contraband; and/or multiple positive tests for substance abuse. Given the frequency of relapse in substance abuse treatment, the use of drugs or alcohol did not automatically result in discharge. Each situation was evaluated individually and the resident was counseled and given a second opportunity by developing an individual plan of correction. As a rule, most of the inmates “sent back” to the main prison were eventually discharged directly into the community from the prison at a later date. [Note: A small number were readmitted to TLC for a second time-as described below].

Results

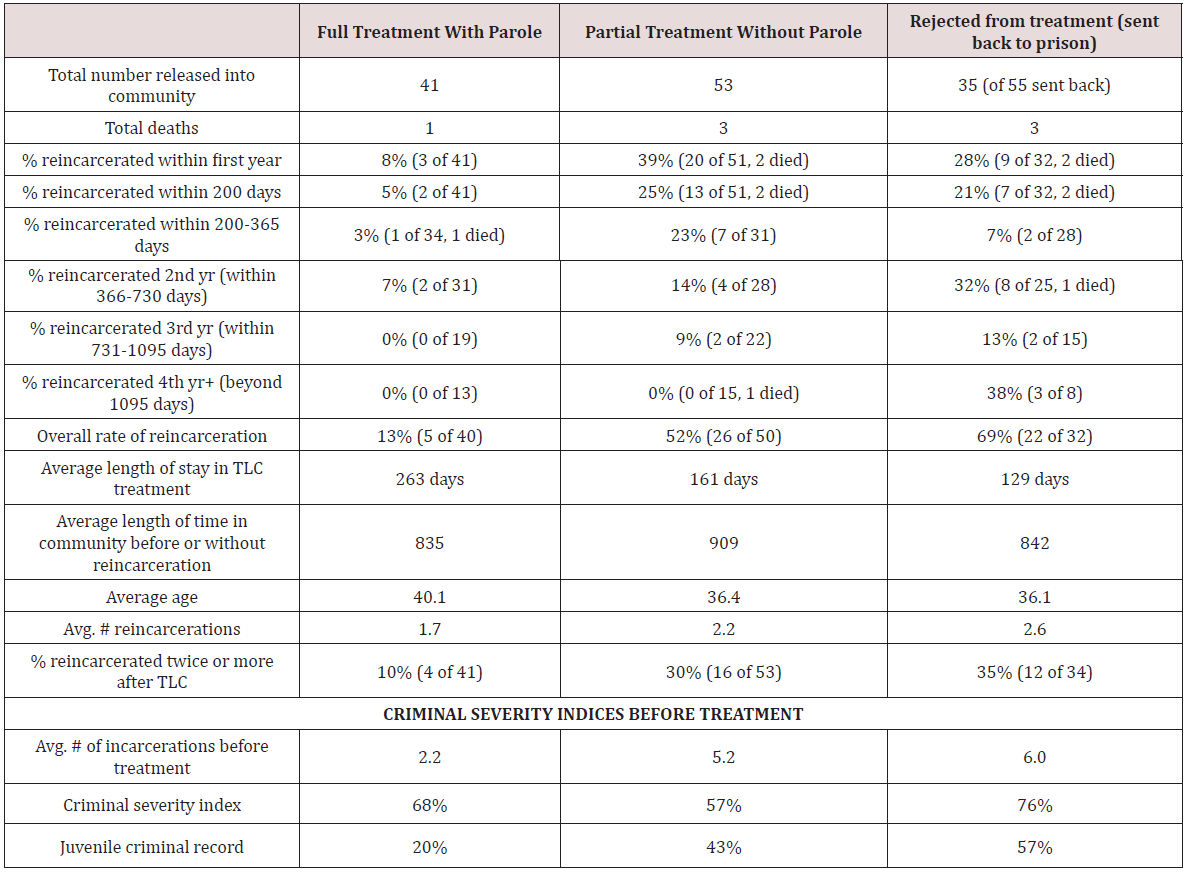

The average age of the participants was 37.2 years at the time of discharge from TLC. The follow-up period reached at least three years or more for 98 participants. Seven died. Preand post-treatment reincarcerations were determined using Bermuda Department of Correction (DOC) records. One of the 150 admissions to the TLC was still in residence as of closing date of the analysis. Of the 149 men discharged from the TLC, 94 offenders (64%) “Completed full or partial treatment/reentry” and 55 (37%) were “rejected from treatment” and sent back to the main prison for disciplinary reasons. Of the 94 offenders who were discharged directly from the treatment center, 41 were “Recommended for Parole” and 53 were released upon their “Earliest Release Date.” Of the 55 who were “rejected from treatment,” 34 were released into the community directly from the main prison.

The study examined three groups as follows:

a. Full Treatment/Reentry with Parole Group: A total of 41 men were recommended for parole after completing the treatment/reentry program at the TLC and were discharged directly to the community where they continued under supervision by Parole. The Parole Recommendation group was considered the “full treatment group” because they completed a full course of treatment at the TLC and was then judged ready for release to the community by the treatment team.

b. Partial Treatment/no Parole Group: A total of 53 offenders were discharged from the TLC into the community upon reaching their predetermined “Earliest Date of Release” (ERD). In a strict sense, the ERD group received only “partial treatment” because they were discharged on the ERD regardless of their progress (or lack of progress) in the treatment program at that juncture.

c. Rejection from Program Group: Of the 55 offenders who were “rejected” from the rehabilitative program and sent back to the main prison for disciplinary reasons, a total of 34 were subsequently discharged directly from the main prison into the community. Thirteen of these inmates were re-admitted to the treatment center, including one inmate who was readmitted twice. Of these 13 men admitted more than once to TLC, ten were sent back to the main prison after being rejected from the program for a second time. Of these ten repeat admissions, one was rejected from the program for a third time for rule violations, two completed full treatment/reentry with parole, and seven were discharged from the TLC after partial treatment/reentry without parole. [Note: Three of the 13 repeated admissions were released to the community (two from the treatment center and one from the main prison), then reincarcerated, and then readmitted to the TLC for a second time. Thus, there were a total of 128 total outcomes in which an offender was released into the community.

Outcomes by Treatment Comparison Groups

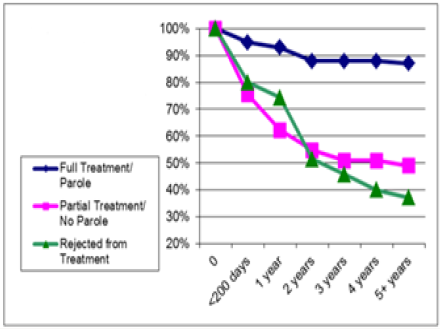

Over the course of eight years, 64% of those admitted to the TLC completed all or part of the rehabilitative program, while 37% were rejected from treatment. The “full treatment with parole” group (those completing the therapeutic community and work release program and released under parole supervision) had the best outcomes, by far, of the three comparison groups. The group with partial treatment without parole supervision showed slightly better outcomes than those who were rejected from treatment and sent back to the main prison for rule violations.

The overall reincarceration rate for the full treatment/parole group was just 13% compared to 52% for the partial treatment/ no parole group and 69% of the rejection-from-treatment group. The full treatment/parole group had a significantly lower rate of reincarceration, X2 (2, N=129)=20.36, p<.001, and fewer average reincarcerations, F (2,126)=7.54, p<.001. The partial treatment/ no parole and rejection-from-treatment groups did not differ significantly on either outcome, but the partial treatment/no parole group showed the highest rate of reincarceration during the first half year (25%) and second half year of reentry (23%), while the rejection-from-treatment group showed the highest rates of reincarceration in every year thereafter. The rejection-fromtreatment group also had the highest average of 2.6 reincarcerations compared to 2.2 and 1.7 for the partial treatment/no parole and full treatment/parole groups respectively.

As would be expected, the full treatment/parole group had the longest average length of stay in the TLC at 8.8 months, which was nearly double that of the partial treatment/no parole group at 5.4 months and that rejected-from-treatment group (4.0 months). At 40.1 years, the full treatment/parole group was an average of 4 years older than the partial treatment/no parole and rejectionfrom- treatment groups (36.4 and 36.1 years).

Outcomes by Substance Abuse Type

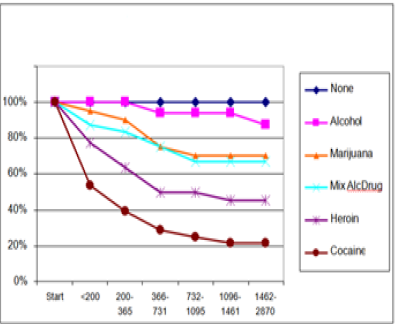

Offenders were classified into eight categories based on their histories and patterns of substance abuse/dependency. Those with a clear predominant type of substance abuse were classified as Alcohol (n=19), Marijuana (n=24), Cocaine (n=30), Heroin (n=27) and Cocaine and Heroin (n=6). Those primarily abusing alcohol in combination with other drugs were classified as “Mixed Alcohol and Drug” (n=30) and those with mixed drug abuse without alcohol were classified as “Mixed Drug” (n=5). Finally, a group of offenders who evidenced no major problems with alcohol or drugs were classified as “None” (n=9) (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 3 shows the survival rates for six of the eight groups. (Mixed Drug and Mixed Cocaine/Heroin were too small for analysis). The Cocaine abusers had the highest rate of reincarceration at 79% with an average of 3.1 post-treatment reincarcerations, followed by the Heroin abusers at 55% with 2.3 reincarcerations, and the Mixed Cocaine/Heroin abusers at 50% with 1.0 reincarcerations. The cocaine and heroin abusers were reincarcerated at double and triple the rate of other categories of substance abuse. As shown in the survival curves in Figure 2, a whopping 46% of cocaine abusers were reincarcerated within 200 days of release and 61% were jailed within the first year. This was double that of the heroin abusers and seven to eight times higher than the other categories of substance abuse. Cocaine abusers had a significantly higher rate of re-incarceration than all groups except Heroin and Mixed Cocaine/ Heroin, 2(5, N=102)=27.85, p<.001, while Heroin abusers had a significantly higher rate than Alcohol or No Drugs, 2(2, N=47)=12.55, p<.002.

In contrast, offenders with no identified substance abuse had zero reincarcerations. Primary alcohol abusers also did very well in the community with a low 13% rate of reincarceration and an average of 1 reincarceration after treatment. Mixed Alcohol and Drug abusers and primary Marijuana abusers did relatively well with reincarceration rates of 33% and 30% respectively, while those with Mixed Drug abuse had a 20% reincarceration rate. These groups had averages of 1.0, 1.7, and 1.0 reincarcerations respectively. The cocaine and heroin abusers did poorly in nearly every respect. They entered treatment with the highest average number of previous incarcerations (8.3 and 6.0 respectively). Once admitted, they had the poorest rates of program completion (50% and 56%) and short lengths of stay in treatment (157 and 166 days). Following discharge, the cocaine and heroin abusers achieved fewer days before reincarceration (307 and 333 days) and were prone to multiple reincarcerations after discharge (3.1 and 2.3). Comprising 20% of the men served the primary cocaine abusers emerged as the most challenging offender subpopulation with both the highest and fastest reincarceration rates. As a group they averaged just 10.1 months before reincarceration and had an average of 3.1 reincarcerations in the years after release from the TLC.

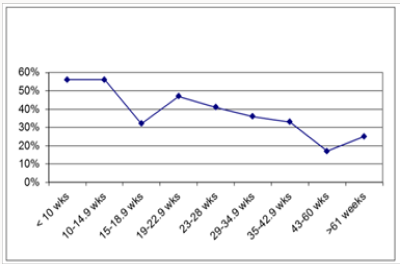

Outcomes by Length of Treatment

There was a significant negative correlation between reincarceration and completion of treatment (r=-0.27, p<.01). Those who were discharged from the treatment center (either through Parole or Earliest Release Date) were less likely to be reincarcerated than those rejected-from-treatment and sent back to prison. There was also a significant negative correlation between the length of stay in the TLC program and reincarceration (r=0.19, p<.05). Offenders who stayed longer in treatment were less likely to be reincarcerated. Figure 2 shows a clear trend between reincarceration rates and number of days in treatment. Of the offenders who received less than 10 weeks of treatment (n=16) and those receiving 10-15 weeks (n=18) 56% of each category were reincarcerated compared to just 32% of those receiving 15-19 weeks (n=19). The percentage of reincarcerated offenders then increased to 47% for those receiving 19-23 weeks of treatment (n=17), but steadily declines over time from 41% for 23-28 weeks (n=17) to 36% for 29-35 weeks (n=17) to 33% for 35-43 weeks (n=12) to a low of 17% for those receiving 43-60 weeks of treatment (n=12). An increase in reincarceration rate to 25% for those receiving 61 weeks or more may be distorted by the small number in this grouping (n=4).

Outcomes by Criminal Severity

The analysis also looked at outcomes in terms of three indices of criminality. For each index, those with the more serious and/ or lifelong criminality had lower rates of program completion and shorter lengths of stay in treatment, and had higher rates of reincarceration, higher numbers of reincarcerations, and shorter time in the community before reincarceration following discharge.

Criminal Severity: “Severe Criminality” was defined as serving a sentence of 5 or more years and/or having had five or more previous incarcerations. “Mild Criminality” was defined as serving less than 5 years and having less than 5 previous incarcerations. Two thirds of the inmates admitted to TLC (67%) met the criteria for Severe Criminality. 48% of the severe criminality group were reincarcerated compared to 28% of the Mild group. Moreover, those in the Severe group were reincarcerated an average of 9.5 months sooner than the Mild group. It is interesting that the severe group tended to stay in treatment for an average of 5.4 weeks longer than the Mild group.

Juvenile History: 42% of the men had a juvenile criminal record. It is notable that 57% of the offenders meeting the severe criteria also had a juvenile criminal history compared to only 16% of the Mild offenders. Men with a lifelong criminal history were reincarcerated at more than twice the rate of those without, 64% compared to 27%. Moreover, the men with a juvenile criminal record were reincarcerated an average of 14.4 months sooner than those without. Average length of treatment was virtually the same for both groups.

Previous Incarcerations: The third index of criminal severity was the number of previous incarcerations. In total, the offenders served by TLC had an average of 4.7 previous incarcerations. As shown in Tables 1-3, there is a clear pattern of increasingly poor outcomes based on the number of incarcerations prior to treatment. Only 11% of first time inmates and 28% of second time inmates were reincarcerated, compared to 36% of those with 2-4 incarcerations, 63% of those with 5-9 incarcerations, and 82% of those with over 10 incarcerations. Similarly, first time inmates achieved an average of three years in the community without reincarceration compared to just one year for those with 10 or more previous incarcerations.

Discussion

This long-term outcome study clearly shows the value of reentry treatment programming for reducing criminal recidivism for substance abusing inmates. Offenders who completed treatment and received follow-up parole supervision remained free of reincarceration at four and five times the rate of those receiving partial treatment/no parole or rejected-from-treatment. This dramatic difference in recidivism was clear within the initial six months of release and continued to be true over the course of one year, two years, three years, and beyond. The best three-year outcomes achieved by comparable reentry treatment programs for substance abuse have been about 25% reincarceration. With a rate of just 13% for the first two years and 0% for three years and beyond (as much as eight years), there may be particular or unique features of the Transitional Living Center that help account for its superior results.

Although it is not possible to tease out the contributions of each of its components, it appears that the strong work release program had an especially powerful rehabilitative effect. Prior to release from the treatment center, nearly every participant experienced a considerable period of real-world employment in a job that was matched to his individual interests and aptitudes. The TLC program fostered partnerships with dozens of community businesses so that virtually every inmate released from the TLC (96%) was already employed full-time prior to release. This was not true for those rejected from treatments, who were reincarcerated as twice the rate of the fully employed treatment groups (69% vs. 34%). TLC’s emphasis on financial responsibility may have also been a unique component. In combination with money management education, the program participants were required to direct major amounts of their incoming pay toward rent deposits, child support, and debt reduction, as applicable. It is notable that, prior to this requirement in the third year of the program, many men would accumulate a sizeable nest egg, which often became a tempting fortune to be “blown” in celebration and relapse upon release.

The results also show that offenders with increasingly longer treatment (which itself entails longer experience in responsible employment) had increasingly better outcomes. Those with less than 10 weeks of treatment were reincarcerated as nearly twice the rate of those who received more than 10 weeks. The ideal length of stay appeared to be about six months. Outcomes could have been greatly improved for the partial treatment/no parole group by making referrals into the TLC program sooner, thus giving more rehabilitative time to the offenders before their Earliest Release Date (ERD) for completion of sentence. Alternatively, the TLC program could have been more effective if it had the authority to “hold” offenders until they were more ready to return to the community (as was true for the full treatment/parole group).

Finally, the woeful rate of reincarceration for cocaine abusers (79%), and for heroin abusers to a lesser degree (55%), points to the need for more intensive, lengthy and/or specialized treatment programming for these substance abuse types. In addition to the value of mandating a longer period of treatment (cocaine abusers completed an average of three weeks less of treatment than other groups), specialized treatment modules and community supports may be necessary for cocaine- and heroin-abusing offenders [16]. Similarly, extended treatment may be more helpful to offenders with high numbers of previous incarcerations (e.g., 82% of offenders with more than 10 incarcerations were reincarcerated). Conversely, less treatment may be needed for first time offenders (only 11% were reincarcerated), which can help conserve available resources.

Limitations of the Study: It is important to acknowledge that the findings of this study cannot be easily compared with other studies because of differences in methods or other factors. While the circumscribed nature of this island nation allowed the researchers to determine relatively long-term outcomes for 100% of the participants, the TLC treatment program results may have limited generalizability because of its unique and rich combination of program components (TC, work release, rehabilitation, reentry) and several methodological issues.

First, there is a potential for selection bias because of the lack of clarity or consistency in applying admission criteria. One of the greatest practical challenges for this treatment program was its lack of control over referrals by correctional authorities. The program accepted anyone who was referred. This meant that some offenders were not appropriate (e.g., severe mental illness, institutional behavioral problems) or not adequately prepared or motivated for participation in a treatment program. This resulted in an extremely high rate of subsequent rejection and drop-out from the treatment condition. Another major problem was that individuals were enrolled without enough time to benefit fully from the treatment before the end of their sentences, which resulted in a very high number of “partial” treatment cases. These confounding factors make it hard to clearly differentiate the partial treatment and rejected-from-treatment conditions as distinctive groups for comparison. Given the numbers of inappropriate, ill-prepared, and unmotivated subjects, the study certainly cannot be accused of “cherry picking” candidates who would do well. If anything, the referral problem “stacked the deck” against positive treatment outcomes. Another limitation of the study is the small sample size, especially with regard to analyzing outcomes for sub-types of substance abuse that had less than 10 subjects.

References

- Hughes T, Wilson D, Beck A (2001) Trends in State Parole, 1990–2000. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, USA.

- Langan P, Levin D (2002) Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 1994. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

- Beck A (2001) Trends in State Parole, 1990-2000. State and Federal prisoners returning to the community: Findings from the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Listwan S, Cullen F, Latessa E (2006) How to prevent prisoner reentry programs from failing: Insights from evidence-based corrections. Federal Probation 70: 19-25.

- Swan S, Jennings J (2008) Bermuda Transitional Living Center: A community reintegration program for substance abusing offenders that combines therapeutic community and work release principles. Presentation to the 2008 National Mental Health Conference, “Unlock the Mystery: Managing Mental Health from Corrections to Community,” Indianapolis, IN.

- Taxman F, Young D, Byrne J, Holsinger A, Anspach D (2002) From Prison Safety to Public Safety: Best Practices in Offender Reentry. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

- Open Minds (2008) Getting out and staying out: New York prisoner reentry program has three-year recidivism rate of 10%.

- Harrison L (2001) The revolving prison door for drug involved offenders: Challenges and opportunities. Crime and Delinquency 47(3): 462-485.

- Wexler H, De Leon G, Thomas G, Kressel D, Peters J (1999) The Amity Prison Therapeutic Community evaluation: Reincarceration outcomes. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 26(2): 147-167.

- McCollister K, French M, Prendergast M, Wexler H, Sacks S, et al. (2003) Is in-prison treatment enough? A cost-effectiveness analysis of prisonbased treatment and aftercare services for substance-abusing offenders. Law and Policy 25: 63-82.

- Knight D, Simpson D, Hiller M (1999) Three year incarceration outcomes for in-prison Therapeutic Community treatment in Texas. The Prison Journal 79: 337-351.

- Martin S, Butzin C, Saum C, Inciardi J (1999) Three-year outcomes of therapeutic community treatment for drug-involved offenders in Delaware: From prison to work release to aftercare. The Prison Journal 79(3): 294-320.

- National Institute of Justice (2005) Reentry programs for women inmates. National Institute of Justice Journal 252.

- Butzin C, Martin S, Inciardi J (2005) Treatment during transition from prison to community and subsequent illicit drug use. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 28(4): 351-358

- Simpson D, Wexler H, Inciardi J (1999) Special issue on drug treatment outcomes for correctional settings, Parts 1 & 2. The Prison Journal 79.

- Simpson D, Joe G, Broome K (2002) A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 59(6): 538-544.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...