Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-5910

Review Article(ISSN: 2638-5910)

Inequalities in Diabetes in the USA Volume 2 - Issue 5

Nasser Mikhail MD* and Soma Wali MD

- Department of Medicine, OliveView-UCLA Medical Center, David-Geffen-UCLA School of Medicine, USA

Received: July 01, 2020 Published: July 10, 2020

Corresponding author: Nasser Mikhail MD, Chief, Endocrinology Division, Department of Medicine, OliveView-UCLA Medical Center, David-Geffen-UCLA School of Medicine, USA

DOI: 10.32474/ADO.2020.02.000148

Abstract

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Background: Diabetes disproportionably impacts minorities in the USA.

Objective: To review the latest data regarding diabetes epidemiology and management among different ethnic groups in the USA.

Methods: PubMed research of all pertinent articles up to June 29, 2020. Search terms included diabetes, ethnicity, African Americans, Blacks, Hispanics, Latinos, Asians, minorities, glycemic control, obesity, lifestyle changes, treatment, metformin, sodiumglucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors. Type of studies included are randomized, observational, epidemiological, consensus guidelines, and review articles.

Results: Diabetes prevalence and incidence in adults continue to increase among African Americans and Hispanics. In youths, the fastest increase in type 1 and type 2 diabetes occurs among Asians/Pacific Islanders followed by Hispanics and African Americans. The gap in glycemic control between Whites and minorities is widening. Whereas mortality rates decreased in patients with diabetes overall, the least mortality reduction was observed among Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks. The diabetes epidemic among nonwhites patients is mainly due to obesity and physical inactivity. Lifestyle changes are generally effective for both prevention and treatment of diabetes among minorities. Metformin may be particularly effective among African Americans. Metformin and sodiumglucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are the most convenient drugs for treatment of diabetes in minorities.

Conclusion: Substantial disparities still exist in the USA with respect to diabetes incidence, glycemic control, and mortality.

Keywords: Ethnicity; Disparities; Diabetes; Obesity; Prevention; Treatment; Lifestyle changes

Introduction

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

According to the World Health Organization, equity is the absence of avoidable, unfair, or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or by other means of stratification [1]. Therefore, health equity implies that everyone should have a fair opportunity to attain his/her full health, and that no one should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential [1]. Unfortunately, marked ethnic/racial disparities in the USA exist with respect to almost all aspects of diabetes and its care. Thus, minority groups are disproportionately affected in terms of diabetes incidence and prevalence, metabolic control, complications, prevention, and treatment. The causes of these disparities are complex but obesity among minorities play a major role. The main purpose of this article is to provide an update on ethnic/racial disparities in diabetes in the USA and to discuss the most effective ways of diabetes prevention and treatment among minorities. We used the same terminology for the racial/ethnic group (e.g. Hispanics versus Latinos) as it appears in the corresponding reference.

Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

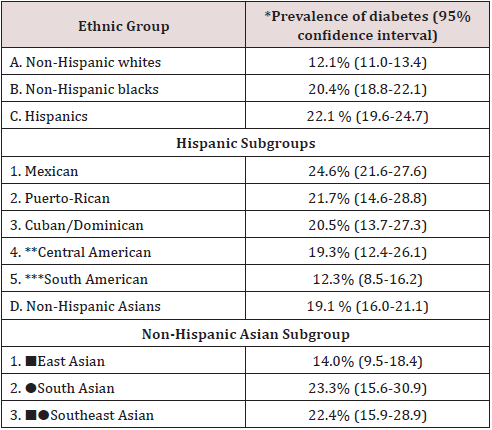

According to 3 surveys conducted by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) between 2011 and 2016, weighted age and sex-adjusted prevalence of total diabetes i.e. diagnosed and undiagnosed was 12.1% for non-Hispanic white, 20.4% for non-Hispanic black, 22.1% for Hispanic and 19.1% for non-Hispanic Asian adults (overall P<0.001) [2]. The prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes generally followed similar pattern: 3.9% for non-Hispanic white, 5.2% for non-Hispanic black, 7.5% for Hispanic, and 7.5% for non-Hispanic Asian adults (overall P < 0.001) [2]. Marked heterogeneity in diabetes prevalence are present within the same ethnic group (Table 1).

Table 1: Estimated prevalence of diabetes, diagnosed and undiagnosed, in the USA among persons 20 years or older among different ethnic groups [adapted from reference 2].

*Weighted age- and sex-adjusted (95% confidence interval).

** Central America: Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras,

Nicaragua, Panama, Salvador.

*** South America: Argentina, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador,

Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela.

■East Asia: China, Japan, Korea.

●South Asian: India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal,

Bhutan.

■●Southeast Asia: Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand,

Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore.

Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Following a steady increase in diabetes incidence in adults from 1990 to 2007, it started to decrease from 2008 through the last National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) conducted in 2017 [3]. However, this decrease in incidence was driven primarily by non- Hispanic whites (annual percentage change of -5.1% (P=0.002) followed by Asians (annual percentage change -3.4% (P=0.06), whereas incidence rates among Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks did not decrease [3]. In fact, the latest age-adjusted data for 2017- 2018 indicated that incidence of diagnosed diabetes in adults were highest in Hispanics (9.7 per 1,000 persons), followed by non- Hispanic blacks (8.2 per 1,000 persons), and Asians (7.4 per 1,000 persons), whereas non-Hispanic whites had the lowest incidence (5.0 per 1,000 persons) [4].

Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

The most recent National Diabetes Statistics Report showed that 34.5% of all US adults had prediabetes (defined as HbA1c 5.7% to less than 6.5%, or fasting plasma glucose 100 to less than 126 mg/dl, or 2-hr postprandial plasma glucose 140 to less than 200 mg/dl) [4]. The prevalence of prediabetes was stable from 2005-8 to 2013-2016 [4], and not statistically significant between racial/ ethnic groups and various education levels: 31.0 % among Whites, 36.8% among non-Hispanic blacks, 36.1% among Hispanics and 33.0% among Asians [4].

Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

According to the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study, a population-based registry study covering 5 states in the USA, incidence of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes is increasing in youths (defined as persons aged < 20 years) [5]. From 2002 to 2015, the annual relative percent increase was 1.9% and 4.8% in type 1 and type 2 diabetes, respectively [5]. Like the adult population, there were clear ethnic/racial differences in the rate of increase of diabetes in youths [5]. In type 1 diabetes, the steepest increase in incidence was among Asians/Pacific Islanders (4.4% per year), followed by Hispanics (4.0% per year), then Blacks (2.7%/year), and finally Whites 0.7% per year [5]. In type 2 diabetes, similar order was observed. Thus, the fastest increase was among Asians/ Pacific Islanders (7.7% per year), followed by Hispanics (6.5% per year), Blacks (6.0%/year), American Indians (3.7% per year), and finally Whites (0.7% per year). The latter increase among Whites was not statistically significant (95% CI, -1.35 to 2.94) [5]. Reasons of increase in type 1 diabetes are unclear. Meanwhile, the increased incidence in type 2 diabetes is likely due to the increase in obesity in US youths, particularly among minorities [6].

Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

In 2016, the crude (unadjusted) national prevalence of gestational diabetes was 6% [7]. In terms of ethnicity, prevalence of gestational diabetes follows a characteristic pattern. The lowest prevalence exists among non-Hispanic blacks 4.8%, followed by Whites 5.3%, then Hispanics 6.6%, then American Indians/Native Alaskans, and highest in Asians 11.1% [7]. However, despite the fact that prevalence of gestational diabetes is lowest among black women, their risk of developing subsequent type 2 diabetes was the highest compared with other racial/ethnic/groups [8]. For instance, the adjusted hazard ratio of developing diabetes after gestational diabetes was 7.6 and 4.4, among Black and White women, respectively, P=0.028) [8].

Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

The African immigrant (African-born) is one of the fastest growing immigrant groups in the USA [9]. Using data from the NHIS, Alma-Ruth et al [10] reported that age-standardized diabetes prevalence was significantly lower in African immigrants than in African- Americans (US-born), 7% and 10%, respectively (P< 0.01) [9]. Furthermore, African immigrants who had lived in the USA for ≥ 10 years were significantly less likely to have diabetes with a prevalence ratio (PR) of 0.61; 95% CI 0.43-0.79), less likely to have overweight/obesity (PR 0.87; 95% CI 0.77-0.96), hypertension (PR 0.69; 95% 0.61-0.78), and to be physically inactive (PR 0.21, 95% 0.15-0.28) [9]. Hence, African immigrants seem to have a more healthy and distinct metabolic profile compared with African Americans.

Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Studies have consistently shown that diabetes control, as reflected by hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) concentrations, is worse in Blacks and Hispanics compared with White race. In a national cohort of persons older than 65 years enrolled in Medicare Advantage Health plans in 2011, Ayanian et al [11] examined the proportions of patients with HbA1c levels ≤ 9.0%. They found this goal was achieved by 84.0%, 80.6%, and 74.6% among White, Hispanic, and Black enrollees, respectively (P<0.001 for the difference between any 2 groups) [11]. Furthermore, available data suggest that the ethnic/racial gap in HbA1c continues to widen. In fact, analysis of NHANES conducted between 2003 and 2014 showed that HbA1c values tend to worsen among African American and Mexican American patients with type 2 diabetes, whereas corresponding values tend to improve among White patients [12]. It should be emphasized, however, that the difference in HbA1c levels between Black and White persons may be attributed in part to racial factors possibly due to difference in glycation of hemoglobin [13]. Thus, on average, HbA1c levels are 0.4 percentage points (95% CI, 0.2-0.6% percentage points) higher among Blacks compared with White individuals for a given mean blood glucose concentrations [13].

Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Serial analysis of the NHANES data between 2005 and 2016 suggests that diabetes care cascade has not significantly improved during that period [14]. Indeed, only 23-25% of patients met the composite goal of targets of HbA1c (<7-8.5%, depending on age and complications), blood pressure (<140/90 mmHg), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (<100 mg/dl), and no smoking [14]. These proportions of patients did not change between 2005 and 2016 [14]. Furthermore, there were obvious ethnic disparities in achieving this goal [14]. For example, in 2013-2016, 25% of non-Hispanic white patients attained he previous composite goal, compared with only 14% of non-Hispanic blacks, and 18% of Hispanic patients [14].

Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

In general, ethnic/racial minorities have more frequent macrovascular and microvascular diabetes complications compared with Whites [10,15]. The largest available National data showed that in 2010, incidence (cases per 10,000) of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) were more than double in Blacks versus Whites 36.6 versus 16.0 [10]. Corresponding rates for lower-extremity amputation were 40.0 versus 20.4, for stroke 63.1 versus 39.0, and for hyperglycemic death 2.2 versus 1.4. A notable exception was the incidence of acute myocardial infarction, which was lower in Blacks compared with Whites, 32.5 versus 37.5, respectively [10]. No corresponding data regarding the Hispanic patients were reported [10].

Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Mansour et al [16] reported significant ethnic disparities in mortality rates in patients with diabetes who participated in the NHANES surveys during 1999-2010. Follow-up of this cohort revealed that all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) mortality decreased in all ethnic groups with diabetes. However, the magnitude of reduction in CV mortality significantly differed between various ethnic groups [16]. Thus, Whites experienced the largest reduction in CV mortality from 20.4% down to 14.5%, followed by Non- Hispanic Blacks from 20.6% to 16.3%, whereas Hispanics had only a marginal reduction from 18.4% to 17.5% [16]. Similarly, recent analysis of NHIS conducted from 1997 to 2017 showed a significant decline in CV complications among White patients only, whereas no significant decline was observed among Black or Hispanic patients [17]. Taken together, while mortality rates decreased in patients with diabetes overall, the least mortality reduction was observed among Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks. This finding is in accord with NHANES data mentioned above showing that diabetes care during 2005-2016 was worst among minorities [14].

Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Causes of high prevalence of diabetes in minorities are multi-factorial [18]. The growing obesity epidemic is likely the main driver of diabetes among minorities. In fact, non-Hispanic blacks have the highest prevalence of obesity, whereas Mexican Americans have the highest annual increase in obesity and in waist circumference [6]. Likewise, there is steady increase in obesity in US youths (2-19 years) among non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans, but recent decline among non-Hispanic whites [6]. In 2030, it is predicted that severe obesity defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35 kg/m2 will be highest among non-Hispanic blacks 31.7% (95% CI, 29.9-33.4), followed by Hispanics 24.5% (95% CI, 22.8-26.2), and non-Hispanic whites 23.4% (95% CI 22.1-24.8) [19]. Other causes of diabetes disparities include high-sugar diet, food insecurity [20], physical inactivity, increase insulin resistance independent of adiposity [18], health illiteracy, low education and socio-economic levels [4], lack of health insurance, decrease adherence to medications [21], and communication/language barriers. Genetic factors for diabetes susceptibility contribute similarly to diabetes risk across race/ethnicities [18]. Therefore, genetic differences are unlikely to play a major role in ethnic/racial diabetes disparities

Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

In subjects pertaining to minority groups, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends screening for diabetes and prediabetes by fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c, or oral glucose tolerance test if they have a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (or ≥ 23 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) [22]. If results are normal, testing should be repeated at a minimum of 3 year-intervals [22]. Patients with prediabetes should be tested yearly [22].

Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Lifestyle changes

Since obesity is the main cause of high incidence of type 2 diabetes in general, and among minorities in particular, weight loss strategies including diet and exercise are essential to prevent or at least to delay onset of diabetes. In the landmark trial of Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) that included 3234 multiethnic individuals at high risk for diabetes, participants were randomized to a lifestyle modification program, metformin 850 mg bid, or placebo [23]. After an average follow-up of 2.8 years, incidence of diabetes was reduced by 58% and 31 % by lifestyle changes and metformin, respectively compared to placebo [23]. It was encouraging that sub-group analysis of the DPP showed that lifestyle intervention tended to be more effective among minority groups with 61-71% reduction in incidence of diabetes compared with 51% reduction among white subjects [24]. Due its success, the DPP approach was implemented in several studies including Hispanics [24] American Indians/Alaska Natives [25], African American [26] and as part of faith-based lifestyle intervention in African American churches [27]. In addition, culturally adapted lifestyle intervention was attempted for prevention of diabetes among Hispanics [28]. In general, the previous studies were met with limited or partial success because of short duration of followup, high attrition rates, and female preponderance [24-28].

Metformin

Although metformin, was inferior to lifestyle changes in prevention of diabetes in the DPP [23], its use in this setting may be considered when lifestyle changes are not feasible or successful. In fact, in the DPP, metformin appears more effective in reduction of new-onset diabetes among minorities than among Whites [23]. Thus, African Americans had 44% reduction, followed by Hispanics 31% reduction, then finally Whites 24% reduction (statistical significance between the 3 groups was not reported) [23]. Moreover, studies showed that metformin is particularly effective with respect to diabetes prevention in women with prior history of gestational diabetes, subjects younger than 60 years, and those with higher baseline fasting glucose (≥ 110mg/dl versus 95- 109mg/dl), or HbA1c (6-6.4% versus < 6.0%) [29]. In addition, the ADA recommends consideration of metformin for patients with prediabetes and BMI ≥ 35kg/m2 [29].

Management of diabetes among minorities

Lifestyle intervention: In ‘The Action for Health in Diabetes

(Look Ahead)” trial, 5,145 (36% minorities, 40% men) overweight/ obese subjects with type 2 diabetes were randomized to intensive

lifestyle intervention and a control group of diabetes support

and education [30]. The objective of the lifestyle intervention

is a weight loss of 10% by decreased caloric and fat intake and

increased physical activity [30]. After 8 years of intervention, all

female patients from different ethnic groups lost weight similarly

[30]. Among men, there was a trend toward less weight loss among

African American and Hispanic men compared with Whites [30].

A more recent randomized trial conducted in Illinois evaluated

culturally tailored diet changes and increase physical activity in

low-income African American patients with type 2 diabetes [31].

Compared to standard care group, HbA1c levels were significantly

lower at 6 months, but the difference was no longer significant at

12 and18 months [31].

The ADA recommends diabetes self-management education

(DSME) in all patients with diabetes. The goal of DSME is to increase

the patient’s self-efficacy to manage diet, physical activity, glucose

monitoring, and stress management [32]. In one meta-analysis of

20 randomized trials of African Americans and Hispanics, DSME

programs resulted in modest but significant HbA1c reduction of

0.31% (95% CI, -0.48 to -0.14%) compared with standard care [33].

However, another meta-analysis of 8 African American studies did

not find any significant impact of DSME in improving HbA1c values

[34]. Overall, data suggest that long-term lifestyle intervention

adopted in the Look Ahead trial is generally effective in all ethnic

groups [30]. However, culturally adapted diet and DSME strategies

had limited or no benefit in terms of glycemic control.

Drug therapy for treatment of diabetes among minorities

Metformin: Data derived from electronic health records suggest that African-Americans (n=7,429) with type 2 diabetes have better glycemic response to metformin compared with European Americans (n=8,783), reduction in HbA1c levels being 0.9% and 0.4%, respectively (P<0.001 for the interaction between metformin exposure and race) [35]. These results are generally in agreement with those of the DPP showing superior efficacy of metformin in prevention of diabetes among African Americans (44% reduction of new-onset diabetes versus placebo) [23]. In addition, a subgroup analysis from the DPP showed that African American subjects with prediabetes treated with metformin have significantly greater decrease in fasting plasma glucose concentrations versus Whites up to 2 years after intervention [36].

Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Sodium-glucose co-transporters 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are effective, safe, and easy to administer (once a day orally). In addition, they reduce systolic blood pressure and body weight. Furthermore, they significantly decrease CV and renal events in patients with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk [37,38]. Therefore, these agents are well-suited for treatment of type 2 diabetes in minorities. Unfortunately, ethnic minorities remain underrepresented in the major CV trials of SGLT2 inhibitors [39]. Nevertheless, it is reassuring that the 2 SGLT2 inhibitors empagliflozin and dapagliflozin decreased incidence of CV events in all ethnic groups, including the black patients that constituted approximately 5% of the study populations [37,38]. In a recent randomized trial formed exclusively of African Americans with type 2 diabetes and hypertension, empagliflozin reduced HbA1c levels by 0.78%, mean ambulatory systolic blood pressure by 8.4 mmHg, and body weight by 1.2 kg compared with placebo after 6 months [40].

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Like SGLT2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP- 1) agonists decreased weight, systolic blood pressure, and CV events in patients with type 2 diabetes and established CV disease [41]. Main limitations of these agents are the subcutaneous way of administration (once daily or weekly) and high cost. Secondary analysis of phase III trials showed that glycemic efficacy, weight reduction, and safety of the GLP-1 agonist liraglutide are generally similar between African American, Latino/Hispanic, and White patients [42,43]. In the LEADER trial in which Blacks constituted 8.3% of the study population, CV benefits of liraglutide were similar irrespective of the race [41].

Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

Patient-provider communication is a critical element in health care provision. In one study, Latino patients who switched from language-discordant to language-concordant primary care physician had significant improvement in their glycemic control [44]. Current efforts aiming at standardization of Medical Spanish in Medical Schools represent a step forward to enhance communication and trust between physicians and Hispanic patients with limited English proficiency [45].

Summary and Current Needs

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

In the last decade, ethnic/racial disparities in diabetes incidence, prevalence, metabolic control, complications, and mortality continue to worsen. With respect to incidence of type 2 diabetes, the gap between Whites and minorities has widened in both adults and youths [2-5]. The latter observation is largely due to the steady increase in prevalence of obesity among minorities [6]. The DPP showed that weight loss and increased physical activity were effective in preventing diabetes among all racial groups [23]. Therefore, targeting obesity should be an absolute priority to diminish diabetes incidence in general and among minorities in particular. It is the time to take serious actions nationwide to change the pattern of current diet in the US. Specifically, sweetened beverages, refined carbohydrates, red and processed meats should be minimized as far as possible, and replaced by non-sweetened beverages, whole grain, and fibers [46]. Government should provide incentives for production and promotion of affordable healthy food. Any economic or political barriers that interfere with implementation of these diet changes should be removed. Intensive efforts are urgently needed from Federal and local authorities to reduce socioeconomic and educational discrepancies between Whites and disadvantaged minorities. Unfortunately, the recently recorded disproportionate high rates of infection and mortality caused by COVID 19 among African Americans have uncovered the deep and chronic wounds of health inequities that long existed and still persist in this country [47].

References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence

- Disparities and Trends in Diabetes Incidence

- Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes

- Disparities in Diabetes in Youths

- Disparities in Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes

- Diabetes Prevalence Among African Immigrant Population

- Disparities in Glycemic Control

- Trends and Disparities in Diabetes Care in the US

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Complications

- Disparities in Diabetes-Related Mortality

- Causes of Ethnic/Racial Diabetes Disparities: Role of Obesity

- Guidelines for Diagnosis of Diabetes Among Minorities

- Prevention of Diabetes Among Minority Groups

- Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporters Type 2 Inhibitors

- Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists

- Amelioration of Patient-Provider Communication

- Summary and Current Needs

- References

- World Health Organization (2020) Health equity.Switzerland.

- Yiling J Cheng, Alka M Kanaya, Maria Rosario G Araneta, Sharon H Saydah, Henry S Kahn, et al. (2019) Prevalence of diabetes by race and ethnicity in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA 322(24): 2389-2398.

- Benoit SR, Hora I, Albright AL, Edward W Gregg (2019) New directions in incidence and prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in the USA. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care7(1): e000657.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020) National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. U.S. Depart of Health and Human Services PP: 1-32.

- MayerDavis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea A, Jasmin Divers, Scott Isom, et al. (2017) Incidence trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002-2012. N Engl J Med 376: 1419-1429.

- Wang Y, Beydoub MA, Min J, Hong Xue, Leonard A Kaminsky, et al. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and central obesity leveled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemics. Int J Epidemiol; dyz273.

- Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, Bullard KM (2018) Prevalence and changes in preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes among women who had a live born-United States, 2012-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67(43): 1201-1207.

- A H Xiang, B H Li, M H Black, D A Sacks, T A Buchanan, et al. (2011) Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes risk after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 54(12): 3016-3021.

- AlmaRuth N, Ocran T, Nmezi NA, Botchway MO, Szanton SL, et al. (2020) Comparison of cardiovascular disease risk factors among African immigrants and African Americans: an analysis of the 2010 to 2016 National Health Interview Surveys. J Am Heart Assoc9(5): e013220.

- Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J, Nilka Rios Burrows, Mohammed K Ali, et al. (2014)Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1999-2010. N Engl J Med370: 1514-1523.

- Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM (2014) Racial and ethnic disparities among enrollees in Medicare Advantage Plans. N Engl J Med 371: 2288-2297.

- Smalls BL, Ritchwood TD, Bishu KG, Egede LE (2020) Racial/Ethnic differences in glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes: United States 2003-2014. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(3): 950.

- Bergenstal RM, Gal RL, Connor CG, Gubitosiklug R, Kruger D, et al. (2017) Racial differences in the relationship of glucose concentrations and hemoglobin A1c levels. Ann Intern Med 167(2): 95-102.

- Pooyan Kazemian, Fatma M Shebl, Nicole McCann, Rochelle P Walensky, Deborah J Wexler (2019) Evaluation of the cascade of diabetes care in the United States, 2005-2016. JAMA Intern Med 179: 1376-1385.

- Huabin Luo, Ronny A Bell, Seema Garg, Doyle M Cummings, Shivajirao P Patil, et al. (2019) Trends in racial/ethnic disparities in diabetic retinopathy among adults with diagnosed diabetes in North Carolina,2000-2015. NCMJ 80(2): 76-82.

- Mansour O, Golden SH, Heh HC (2020) Disparities in mortality among adults with and without diabetes by sex and race. J Diabetes Complications 34(3):107496.

- Chiou T, Tsugawa Y, Goldman D, Rebecca Myerson, Matthew Kahn, et al. (2020) Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes-related complications, 1997-2017. J Gen Intern Med35(3): 950-951.

- Golden SH, Brown A, Cauley JA, Marshall H Chin, Tiffany L Gary Webb, et al. (2012)Health disparities in Endocrine disorders: Biological, clinical, and nonclinical factors-An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: E1579-1639.

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, Jessica L Barrett, Catherine M Giles, et al. (2019) Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med381(25): 2440-2450.

- Walker RJ, Grusnick J, Garacci E, Carlos Mendez, Leonard E Egede, et al. (2018) Trends in food insecurity in the USA for individuals with prediabetes, undiagnosed diabetes, and diagnosed diabetes. J Gen Intern Med34(1): 33-35.

- Heisler M, Faul JD, Haward RA,Kenneth M Langa, Caroline Blaum, et al. (2007)Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the Health and Retirement Study. Arch Intern Med 167 (17): 1853-1860.

- American Diabetes Association (2020) Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020.Diabetes Care 43(Supplement 1): S14-S31.

- Knowler WC, BarretConnor E, Fowler SE, Richard F Hamman, John M Lachin, et al.(2002) The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med346(6): 393-403.

- Van Name MA, Camp AW, Magenheimer EA, Fangyong Li, James D Dziura, et al. (2016)Effective translation of an intensive lifestyle intervention for Hispanic women with prediabetes in a community health center setting. Diab Care 39(4): 525-531.

- Jiang L, Johnson A, Pratte K, Janette Beals, Ann Bullock, et al. (2018) Long-term outcomes of lifestyle intervention to prevent diabetes in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: The special Diabetes Program for Indians Diabetes Prevention Program. Diab Care 41(7): 1462-1470.

- Sattin RW, Williams LB, Dias J, Jane T Garvin, Lucy Marion et al. (2016) Community trial of a faith-based lifestyle intervention to prevent diabetes among African-Americans. J Community Health 41(1): 87-96.

- Berkley-Patton J, Thompson CB, Bauer AG,Marcie Berman, Andrea Bradley Ewing, et al. (2020) A multilevel diabetes and CVD risk reduction intervention in African American churches: Project Faith Influencing Transformation (FIT) feasibility and outcomes. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 10: 1007.

- McCurley JL, Gutierrez AP, Gallo LC (2017) Diabetes prevention in U.S. Hispanic adults: A systemic review of culturally tailored interventions. Am J Prev Med 52(4): 519-529.

- American Diabetes Association (2020) Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes -2020. Diabetes Care 43(Supplement 1): S32-S36.

- West DS, Dutton G, Delahanty LM,Helen P Hazuda, Amy D Rickman, et al. (2019) Weight loss experiences of African American, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic white men with type 2 diabetes. The LOOK AHEAD Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 27(8): 1275-1284.

- Lynch EB, Mack L, Avery E, Yamin Wang, Rebecca Dawar, et al. (2019) Randomized trial of a lifestyle intervention for urban low-income African Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 34(7): 1174-1183.

- Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, et al. (2017) Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educator 43: 40-53.

- RicciCabello I, RuizPerez I, Rojas Garcias A, Guadalupe Pastor, Miguel Rodríguez Barranco, et al. (2014) Characteristics and effectiveness of diabetes self-management educational programs targeted to racial/ethnic minority groups: a systemic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. BMC Endocr Disord 14: 60.

- Cunnigham AT, Crittendon DR, White N, Geoffrey D Mills, Victor Diaz, et al. (2018) The effect of diabetes self-management education on HbA1c and quality of life in African-Americans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Services Research 18(1): 367.

- Williams LK, Padhukasahasram B, Ahmedani BK, Edward L Peterson, Karen E Wells, et al. (2014) Differing effects of metformin on glycemic control by race-ethnicity. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 99(9): 3160-3168.

- Zhang C, Zhang R (2015) More effective glycemic control by metformin in African Americans than in whites in the prediabetic population. DiabetesMetabolism 41(2): 173-175.

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Fichett D, Erich Bluhmki, Stefan Hantel, et al. (2015) Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 373(22): 2117-2128.

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE,Lars Køber, Mikhail N Kosiborod, et al.(2019) Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 381(2):1995-2008.

- Hoppe C, Kerr D (2017) Minority under-representation in cardiovascular outcome trials for type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 5(1): 13.

- Ferdinand KC, Izzo JL, Lee J,Leslie Meng, Jyothis George, et al. (2019) Antihyperglycemic and blood pressure effects of empagliflozin in black patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Circulation 139(18): 2098-2109.

- Marso SP, Daniels GH, BrownFrandsen K, Peter Kristensen, Johannes F E Mann, et al. (2016) Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Eng J Med 375(4): 311-322.

- Shomali ME, Orsted DD, Cannon AJ (2017) Efficacy and safety of liraglutide, a once-daily human glucagons-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, in African-American people with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of sub-population data from seven phase III trials. Diabet Med34(2): 197-203.

- Davidson JA, Orsted DD, Campos C (2016) Efficacy and safety of liraglutide, a once-daily human glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, in Latino/Hispanic patients with type 2 diabetes: post-hoc analysis of data from four phase III trials. Diabetes Obesity Metab 18(7): 725-728.

- Parker MM, Fernandez HH, Moffer RW, Richard W Grant, Antonia Torreblanca, et al. (2017) Association of patient-physician language concordance and glycemic control on limited-English proficiency Latinos with type diabetes. JAMA Intern Med 177(3): 380-387.

- Ortega P, Diamond L, Aleman LA,Jaime Fatás Cabeza, Dalia Magaña, et al. (2020) Medical Spanish standardization in U.S. Medical School: Consensus Statement from a multidisciplinary expert panel. Acad Med 95(1): 22-31.

- Neuenschwander M, Ballon A, Weber KS,Teresa Norat,Dagfinn Aune, et al. (2019) Role of diet in type 2 diabetes incidence: umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective studies. BMJ 366: 12368.

- Yancy CW (2020) COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA 323(19): 1891-1892.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...